MacKinnon, Privacy and Facebook

This essay is from MacKinnon’s book Consent of the Networked (2012).

PRIVACY AND FACEBOOK

REBECCA MACKINNON

1

As protests mounted in reaction to Iran’s presidential elections on June 12, 2009, Facebook actively encouraged members of the pro-

2

Then in December 2009, Facebook made a sudden and unexpected alteration of its privacy settings. On December 9, to be precise, people who logged in got an automatic pop-

3

The changes were driven by Facebook’s need to monetize the service but were also consistent with founder Mark Zuckerberg’s strong personal conviction that people everywhere should be open about their lives and actions. In Iran, where authorities were known to be using information and contacts obtained from people’s Facebook accounts while interrogating Green Movement activists detained from the summer of 2009 onward, the implications of the new privacy settings were truly frightening. Soon after the changes were made, an anonymous commenter on the technology news site ZDNet confirmed that Iranian users were deleting their accounts in horror:

Page 300

A number of my friends in Iran are active student protesters of the government. They use Facebook extensively to organize protests and meetings, but they had no choice but to delete their Facebook accounts today. They are terrified that their once private lists of friends are now available to “everyone” that wants to know. When that “everyone” happens to include the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and members of the Basij militia, willing to kidnap, arrest, or murder to stifle dissent, the consequences seem just a bit more serious than those faced from silly pictures and status updates. I realize this may not be an issue for the vast majority of American Facebook users, but it’s just plain irresponsible to do this without first asking consent. It’s even more egregious because Facebook threw out the original preference (the one that requested Facebook keep the list of friends private) and replaced it with a mandate, publicizing what was once private information—

4

“People’s friends could still see one another, however, and there was no way to hide them.”

The global outcry over the exposure of people’s friend lists in December 2009 was so strong that within roughly a day after the dramatic change, Facebook made an adjustment so that users could once again hide their friend lists from public view. People’s friends could still see one another, however, and there was no way to hide them. Everybody’s “causes” and “pages” were still publicly exposed by default, another serious vulnerability for activists. People kept complaining—

5

Eventually Facebook fixed this problem as well, adjusting the privacy options so that information about what pages users follow, or groups they have joined, can be made private. Meanwhile, however, lives of people around the world had been endangered unnecessarily—

Page 301

EXERCISE 8.2

Write a one-

Evaluating Websites

The Internet is like a freewheeling frontier town in the old West. Occasionally, a federal marshal may pass through, but for the most part, there is no law and order, so you are on your own. On the Internet, literally anything goes—

Another problem is that websites often lack important information. For example, a site may lack a date, a sponsoring organization, or even the name of the author of the page. For this reason, it is not always easy to evaluate the material you find there.

Page 302

When you evaluate a website (especially when it is in the form of a blog or a series of posts), you need to begin by viewing it skeptically—

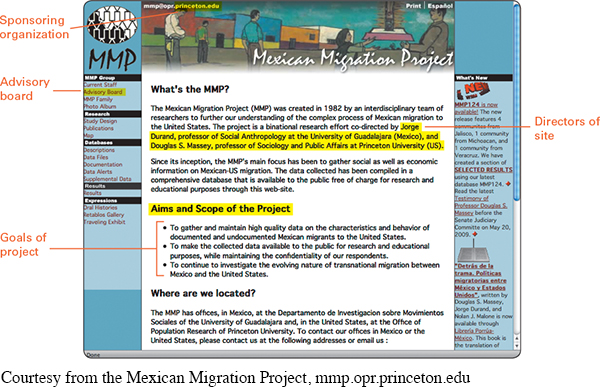

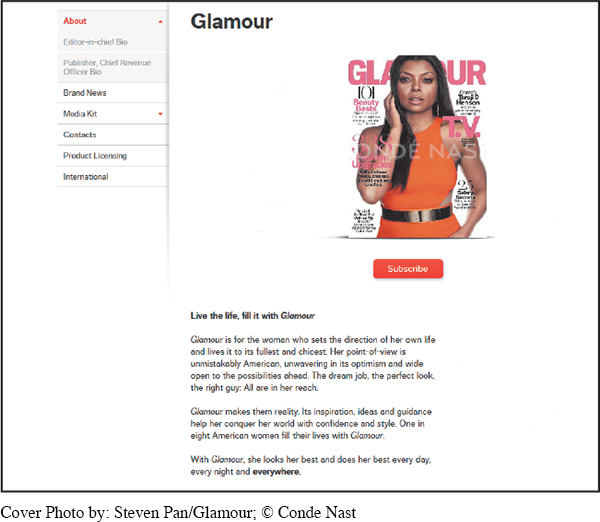

The Web page pictured below shows where to find information that can help you evaluate a website.

Accuracy Information on a website is accurate when it is factual and free of errors. Information in the form of facts, opinions, statistics, and interpretations is everywhere on the Internet, and in the case of Wiki sites, this information is continually being rewritten and revised. Given the volume and variety of this material, it is a major challenge to determine its accuracy. You can assess the accuracy of information on a website by asking the following questions:

Does the site contain errors of fact? Factual errors—

inaccuracies that relate directly to the central point of the source— should immediately disqualify a site as a reliable source. Does the site contain a list of references or any other type of documentation? Reliable sources indicate where their information comes from. The authors know that people want to be sure that the information they are using is accurate and reliable. If a site provides no documentation, you should not trust the information it contains.

Does the site provide links to other sites? Does the site have links to reliable websites that are created by respected authorities or sponsored by trustworthy institutions? If it does, then you can conclude that your source is at least trying to maintain a certain standard of quality.

Can you verify information? A good test for accuracy is to try to verify key information on a site. You can do this by checking it in a reliable print source or on a good reference website such as Encyclopedia.com.

Credibility Information on a website is credible when it is believable. Just as you would not naively believe a stranger who approached you on the street, you should not automatically believe a site that you randomly encounter on the Web. You can assess the credibility of a website by asking the following questions:

Does the site list authors, directors, or editors? Anonymity—

whether on a website or on a blog— should be a red flag for a researcher who is considering using a source. Page 303

Courtesy from the Mexican Migration Project, mmp.opr.princeton.edu

Courtesy from the Mexican Migration Project, mmp.opr.princeton.eduIs the site refereed? Does a panel of experts or an advisory board decide what material appears on the website? If not, what standards are used to determine the suitability of content?

Does the site contain errors in grammar, spelling, or punctuation? If it does, you should be on the alert for other types of errors. If the people maintaining the site do not care enough to make sure that the site is free of small errors, you have to wonder if they will take the time to verify the accuracy of the information presented.

Does an organization sponsor the site? If so, do you know (or can you find out) anything about the sponsoring organization? Use a search engine such as Google to determine the purpose and point of view of the organization.

Objectivity Information on a website is objective when it limits the amount of bias that it displays. Some sites—

Page 304

Keep in mind that bias does not automatically disqualify a source. It should, however, alert you to the fact that you are seeing only one side of an issue and that you will have to look further to get a complete picture. You can assess the objectivity of a website by asking the following questions:

Does advertising appear on the site? If the site contains advertising, check to make sure that the commercial aspect of the site does not affect its objectivity. The site should keep advertising separate from content.

Does a commercial entity sponsor the site? A for-

profit company may sponsor a website, but it should not allow commercial interests to determine content. If it does, there is a conflict of interest. For example, if a site is sponsored by a company that sells organic products, it may include testimonials that emphasize the virtues of organic products and ignore information that is skeptical of their benefits. Does a political organization or special-

interest group sponsor the site? Just as you would for a commercial site, you should make sure that the sponsoring organization is presenting accurate information. It is a good idea to check the information you get from a political site against information you get from an educational or a reference site—Ask.com or Encyclopedia.com, for example. Organizations have specific agendas, and you should make sure that they are not bending the truth to satisfy their own needs. Does the site link to strongly biased sites? Even if a site seems trustworthy, it is a good idea to check some of its links. Just as you can judge people by the company they keep, you can also judge websites by the sites they link to. Links to overly biased sites should cause you to reevaluate the information on the original site.

USING A SITE’S URL TO ASSESS ITS OBJECTIVITY

A website’s URL (uniform resource locator) can give you information that can help you assess the site’s objectivity.

Look at the domain name to identify sponsorship. Knowing a site’s purpose can help you determine whether a site is trying to sell you something or just trying to provide information. The last part of a site’s URL can tell you whether a site is a commercial site (.com and .net), an educational site (.edu), a nonprofit site (.org), or a governmental site (.gov, .mil, and so on).

See if the URL has a tilde (~) in it. A tilde in a site’s URL indicates that information was published by an individual and is unaffiliated with the sponsoring organization. Individuals can have their own agendas, which may be different from the agenda of the site on which their information appears or to which it is linked.

AVOIDING CONFIRMATION BIAS

Page 305

Confirmation bias is a tendency that people have to accept information that supports their beliefs and to ignore information that does not. For example, people see false or inaccurate information on websites, and because it reinforces their political or social beliefs, they forward it to others. Eventually, this information becomes so widely distributed that people assume that it is true. Numerous studies have demonstrated how prevalent confirmation bias is. Consider the following examples:

A student doing research for a paper chooses sources that support her thesis and ignores those that take the opposite position.

A prosecutor interviews witnesses who establish the guilt of a suspect and overlooks those who do not.

A researcher includes statistics that confirm his hypothesis and excludes statistics that do not.

When you write an argumentative essay, do not accept information just because it supports your thesis. Realize that you have an obligation to consider all sides of an issue, not just the side that reinforces your beliefs.

Currency Information on a website is current when it is up-

Does the website include the date when it was last updated? As you look at Web pages, check the date on which they were created or updated. (Some websites automatically display the current date, so be careful not to confuse this date with the date the page was last updated.)

Are all links on the site live? If a website is properly maintained, all the links it contains will be live—that is, a click on the link will take you to other websites. If a site contains a number of links that are not live, you should question its currency.

Is the information on the site up-

to- A site might have been updated, but this does not necessarily mean that it contains the most up-date? to- date information. In addition to checking when a website was last updated, look at the dates of the individual articles that appear on the site to make sure they are not outdated.

Page 306

Comprehensiveness Information on a website is comprehensive when it covers a subject in depth. A site that presents itself as a comprehensive source should include (or link to) the most important sources of information that you need to understand a subject. (A site that leaves out a key source of information or that ignores opposing points of view cannot be called comprehensive.) You can assess the comprehensiveness of a website by asking the following questions:

Does the site provide in-

depth coverage? Articles in professional journals—which are available both in print and online— treat subjects in enough depth for college- level research. Other types of articles— especially those in popular magazines and in general encyclopedias, such as Wikipedia—are often too superficial (or untrustworthy) for college- level research. Does the site provide information that is not available elsewhere? The website should provide information that is not available from other sources. In other words, it should make a contribution to your knowledge and do more than simply repackage information from other sources.

Who is the intended audience for the site? Knowing the target audience for a website can help you to assess a source’s comprehensiveness. Is it aimed at general readers or at experts? Is it aimed at high school students or at college students? It stands to reason that a site that is aimed at experts or college students will include more detailed information than one that is aimed at general readers or high school students.

Authority Information on a website has authority when you can establish the legitimacy of both the author and the site. You can determine the authority of a source by asking the following questions:

Is the author an expert in the field that he or she is writing about? What credentials does the author have? Does he or she have the expertise to write about the subject? Sometimes you can find this information on the website itself. For example, the site may contain an “About the Author” section or links to other publications by the author. If this information is not available, do a Web search with the author’s name as a keyword. If you cannot confirm the author’s expertise (or if the site has no listed author), you should not use material from the site.

What do the links show? What information is revealed by the links on the site? Do they lead to reputable sites, or do they take you to sites that suggest that the author has a clear bias or a hidden agenda? Do other reliable sites link back to the site you are evaluating?

Page 307

Is the site a serious publication? Does it include information that enables you to judge its legitimacy? For example, does it include a statement of purpose? Does it provide information that enables you to determine the criteria for publication? Does the site have a board of advisers? Are these advisers experts? Does the site include a mailing address and a phone number? Can you determine if the site is the domain of a single individual or the effort of a group of individuals?

Does the site have a sponsor? If so, is the site affiliated with a reputable institutional sponsor, such as a governmental, educational, or scholarly organization?

EXERCISE 8.3

Consider the following two home pages—

Page 308

EXERCISE 8.4

Here are the mission statements—statements of the organizations’ purposes—

Page 309

Page 310

EXERCISE 8.5

Each of the following sources was found on a website: Jonathan Mahler, “Who Spewed That Abuse? Anonymous Yik Yak App Isn’t Telling”; Jennifer Golbeck, “All Eyes on You”; Craig Desson, “My Creepy Instagram Map Knows Where I Live”; and Sharon Jayson, “Is Online Dating Safe?”.

Assume that you are preparing to write an essay on the topic of whether information posted on social-