2.5 GLOBALIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development: Globalization has transformed economic development in North America, reorienting employment toward knowledge- 46. U.S. GEOGRAPHY REPORT

46. U.S. GEOGRAPHY REPORT

Like their political systems, the economic systems of Canada and the United States have much in common. Both countries evolved from societies based mainly on family farms. Both then had an era of industrialization followed by a transformation to a primarily service-

The Decline in Manufacturing Employment

By the 1960s, the geography of manufacturing was changing. In the old economic core, higher pay and benefits and better working conditions won by labor unions led to increased production costs. This threatened the high profits demanded by the owners, managers, and shareholders of manufacturing corporations. A number of companies began moving their factories to the southeastern United States where wages were lower and corporate profits higher because of the absence of labor unions.

In 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—a free trade agreement that added Mexico to the 1989 economic arrangement between the United States and Canada—

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) a free trade agreement made in 1994 that added Mexico to the 1989 economic arrangement between the United States and Canada

Another factor in the decline of manufacturing employment has been automation. The steel industry provides an illustration. In 1980, huge steel plants, most of them in the economic core, employed more than 500,000 workers. At that time, it took about 10 person-

Growth of the Service Sector

The economic base of North America is now a broad tertiary sector in which people are engaged in various services such as transportation, utilities, wholesale and retail trade, health, leisure, maintenance, finance, government, information, and education.

As of 2014, in both Canada and the United States about 80 percent of jobs and a similar percentage of the GNI were in the tertiary, or service, sector. There are high-

The Knowledge Economy An important subcategory of the service sector involves the creation, processing, and communication of information—

Industries that rely on the use of computers and the Internet to process and transport information are freer to locate where they wish than were the manufacturing industries of the old economic core, which depended on locally available material resources such as steel and coal. These newer industries are more dependent on skilled managers, communicators, thinkers, and technicians, and are often located near major universities and research institutions.

Crucial to the knowledge economy is the Internet, which was first widely available in North America and has emerged as an economic force more rapidly there than in any other region in the world. With only 5 percent of the world’s population, North America accounted for 11.4 percent of the world’s Internet users in 2014. Roughly 78 percent of the population of the United States uses the Internet, as does 85 percent of the Canadian population, compared to 73 percent of the European Union and 39 percent of the world as a whole. The total economic impact of the Internet in North America is hard to assess, but retail Internet sales increase every year. Indeed, although overall purchases were down during the recession of 2008 to 2011, online purchases in the United States and Canada steadily increased.

The Internet has entered many aspects of life in North America. In the political sphere, social networking (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and others) now plays a large role in recruiting volunteers and eliciting cash contributions, especially during recent U.S. election cycles. Beginning in 2009, social networking through Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube became an integral part of public communication, often referred to on daily TV news programming. It is now a major source of information for North Americans about international events, such as the Arab Spring demonstrations around the Mediterranean.

The growth of Internet-

digital divide the discrepancy in access to information technology between small, rural, and poor areas and large, wealthy cities that contain major governmental research laboratories and universities

Globalization and Free Trade

The United States and Canada are major engines of globalization that impact the world economy through the size and technological sophistication of their economies. Together, they are almost as large as the economy of the entire European Union. North America’s advantageous position in the global economy is also a reflection of its geopolitical influence—

Free trade has not always been emphasized the way it is now. Before its rise to prosperity and global dominance, trade barriers were important aids to North American development. For example, when it became independent of Britain in 1776, the new U.S. government imposed tariffs and quotas on imports and gave subsidies to domestic producers. This protected fledgling domestic industries and commercial agriculture, allowing its economic core region to flourish.

Now, because both are wealthy and globally competitive exporters, Canada and the United States see tariffs and quotas in other countries as obstacles to North America’s economic expansion abroad. Thus, they usually advocate heavily for trade barriers to be reduced worldwide. Critics of these free trade policies point out a number of inconsistencies in the current North American position on free trade. First, North America once needed tariffs and quotas to protect its firms, much like many currently poorer countries still need to do. Furthermore, contrary to their own free trade precepts, both the United States and Canada still give significant subsidies to their farmers. These subsidies make it possible for North American farmers to sell their crops on the world market at such low prices that farmers elsewhere are hurt or even driven out of business (see the vignette below). For example, many Mexican farmers have lost their small farms because of competition from large U.S. corporate farms, which receive subsidies from the U.S. government. Corporate farms in the United States can now sell their produce in Mexico or even relocate there under NAFTA agreements. The critics add that beyond agriculture, in North America, the benefits of free trade go mostly to large manufacturers and businesses and their managers, while many workers end up losing their jobs to cheaper labor overseas, or see their incomes stagnate.

NAFTA Trade between the United States and Canada has been relatively unrestricted for many years. The process of reducing trade barriers began formally with the Canada–

The extent of NAFTA’s impacts are hard to assess because it is difficult to tell whether the many observable changes have been caused by the agreement itself or by other changes in regional and global economies. However, a few things are clear. NAFTA has increased trade, and many companies are making higher profits because they now have larger markets. Since 1990, exports among the three countries have increased in value by more than 300 percent. By value, NAFTA’s exports to the world economy have increased by about 300 percent for the United States and Canada and by 600 percent for Mexico. Some U.S. companies, such as Walmart, expanded aggressively into Mexico after NAFTA was passed. Mexico now has more Walmarts (2400 retail stores) than any country except the United States, which has 4663 (Figure 2.12). Canada has 380 Walmarts.

NAFTA seems to have worsened the perennial tendency of the United States to spend more money on imports than it earns from exports. This imbalance is called a trade deficit. Before NAFTA, the United States had much smaller trade deficits with Mexico and Canada. After the agreement was signed, these deficits rose dramatically, especially with Mexico. For example, between 1994 and 2009, the value of U.S. exports to Mexico increased by about 153 percent, while the value of imports increased 265 percent.

trade deficit the extent to which the money earned by exports is exceeded by the money spent on imports

NAFTA has also resulted in a net loss of about 1 million jobs in the United States. Increased imports from Mexico and Canada have displaced about 2 million U.S. jobs, while increased exports to these countries have created only about 1 million jobs. Some new NAFTA-

As the drawbacks and benefits of NAFTA are being assessed, talk of extending it to the entire Western Hemisphere has stalled. Such an agreement, which would be called the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), would have its own drawbacks and benefits. A number of countries, including Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, are wary of being overwhelmed by the U.S. economy. Even in the absence of such an agreement, trade between North America and Middle and South America is growing faster than trade with Asia and Europe. This emerging trade is discussed in Chapter 3.

The Asian Link to Globalization Another way in which the North American economy is becoming globalized is through the lowering of trade barriers with Asia. One huge category of trade with Asia is the seemingly endless variety of goods imported from China—

U.S. and Canadian companies also want to take advantage of China’s vast domestic markets. For example, the U.S. fast-

Asian investment in North America is also growing. For example, Japanese and Korean automotive companies have located plants in North America to be near their most important pool of car buyers—

Japanese and Korean carmakers succeeded in North America even as U.S. auto manufacturers such as General Motors were struggling. This was primarily because more advanced Japanese automated production systems—

IT Jobs Face New Competition from Developing Countries By the early 2000s, globalization was resulting in the offshore outsourcing of information technology (IT) jobs. A range of jobs— 45. U.S. COMPETITIVENESS

45. U.S. COMPETITIVENESS

Repercussions of the Global Economic Downturn Beginning in 2007

The severe worldwide economic downturn that began in 2007 came on the heels of a long upward trajectory of global economic expansion. A booming housing industry and related growth in the banks that finance home mortgages fueled this growth in the United States. In 2007, the housing industry collapsed as it became clear that much of the growth in previous years had been based on banks allowing millions of buyers to purchase homes with mortgages that were well beyond their means. The growth in the construction industry, based on erroneous assumptions, came to a sudden halt. When too many homebuyers could no longer afford their mortgage payments, the banks that had lent them money and/or the institutions to which the banks had sold these mortgages started to fail. The bank failures produced worldwide ripple effects because so many foreign banks were involved in the U.S. housing market. Between September 2008 and March 2009, the U.S. stock market fell by nearly half, wiping out the savings and pensions of millions of Americans. Similar plunges followed in foreign stock markets, ultimately resulting in a worldwide economic downturn because businesses could no longer find money to fund expansion.

As the recession intensified, job losses in the United States caused a sharp drop in consumption, which further affected world markets, including those in Canada. Thanks to its strong regulatory controls, Canada did not have bank failures. However, because so much of the Canadian economy is linked to exports and imports from the United States (see Figure 2.13), Canada underwent a massive slowdown. During three quarters in 2009, its GNI declined by 3.3 percent and its exports fell by 16 percent. Canada also lost many jobs but its recovery was quicker than that of the United States, possibly because household consumption was buttressed by Canada’s stronger social safety net.

Efforts to deal with the difficulties that caused the recession, as well as the long-

The recession worsened the trend toward larger wealth disparities that has been underway since the 1970s. Disparities are most extreme in the United States, where in 2014 the wealthiest 1 percent of households owned 40 percent of the country’s total wealth, and the next wealthiest 19 percent owned roughly another 53 percent, leaving the remaining 80 percent of the population with only 7 percent of the wealth. Most North Americans are not in favor of this kind of wealth distribution, but there are many political barriers that make it difficult to reduce such inequality.

Interdependencies

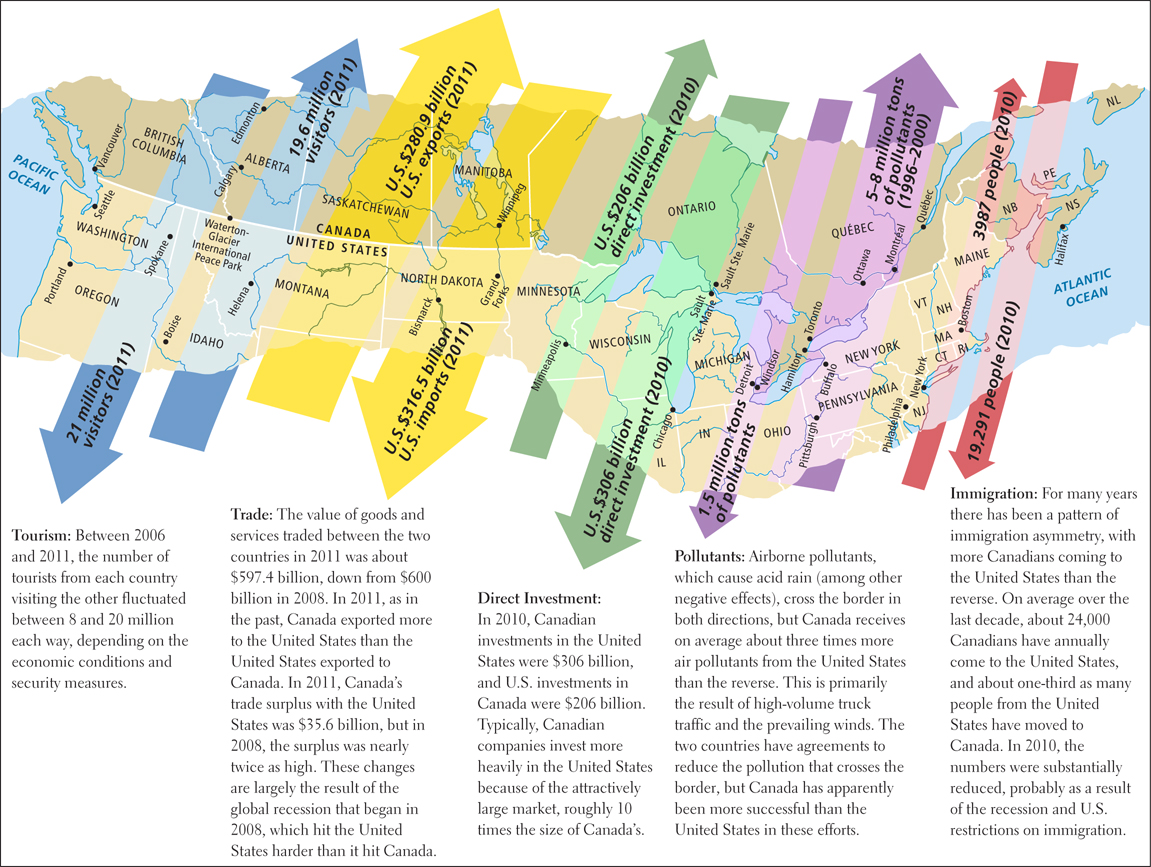

Canada and the United States are perhaps most intimately connected by their long-

Notice, however, that there is asymmetry even in the realm of interdependencies: Canada’s smaller economy is much more dependent on the United States than the reverse. Nonetheless, as many as 1 million U.S. jobs are dependent on the relationship with Canada.

Women in the Economy

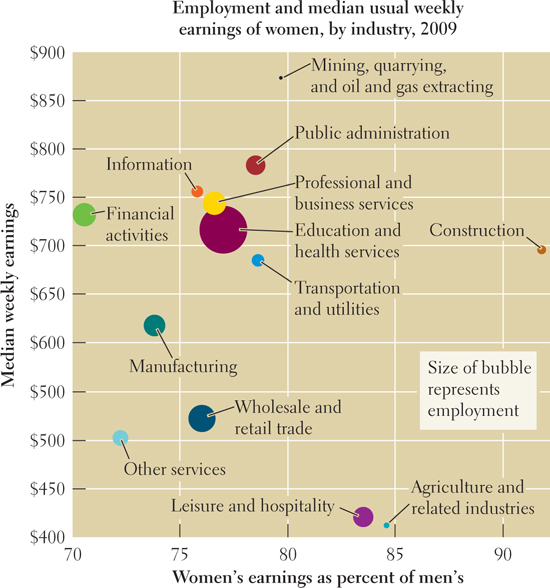

While women have made steady gains in achieving equal pay and overall participation in the labor force, there are still important ways in which they lag behind their male counterparts. On average, U.S. and Canadian female workers earn about 80 cents for every dollar that male workers earn for doing the same job (Figure 2.14). For example, a female architect earns approximately 80 percent of what a male architect earns for performing comparable work. This situation is actually an improvement over previous decades. During World War II, when large numbers of women first started working in male-

North America’s Changing Food-Production Systems

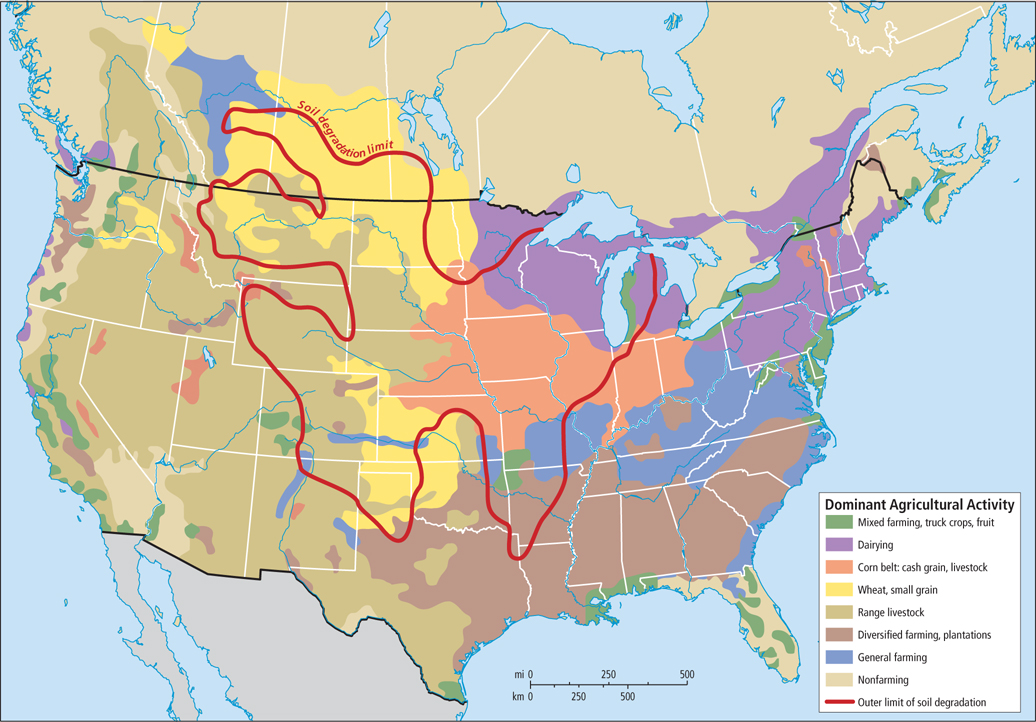

Agriculture remains the spatially dominant feature of North American landscapes, yet less than 1 percent of North Americans are engaged directly in agriculture. North America benefits from an abundant supply of food; the region produces food for foreign as well as domestic consumers (Figure 2.15). At one time, exports of agricultural products were the backbone of the North American economy. However, because of growth in other sectors, agriculture now accounts for less than 1.2 percent of the United States’ GDP and less than 2 percent of Canada’s. Moreover, because both countries are so involved in the global economy, an increasing amount of food in both countries is imported.

The shift to mechanized agriculture in North America brought about sweeping changes in employment and farm management. In 1790, agriculture employed 90 percent of the American workforce; in 1890, it employed 50 percent. Until 1910, thousands of very productive family-

Family Farms Give Way to Agribusiness Family farms began to mechanize and use chemical fertilizers in the late nineteenth century. Mechanical corn-

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Women in Business and Education

Throughout North America, the number of women entrepreneurs is on the rise, and women start nearly half of all new businesses. While women-

In secondary and higher education, North American women have equaled or exceeded the level of men in most categories. In 2008 in the United States, 33 percent of women aged 25 and over held an undergraduate degree, compared to just 26 percent of men. This imbalance is likely to increase because in 2010, U.S. women between the ages of 25 and 29 received 7 percent more undergraduate degrees than men did.

A major part of the transformation of North American agriculture has been the growth of large agribusiness corporations that sell machinery, seeds, and chemicals. These corporations may also produce and process crops themselves on land they own, or they may contract to purchase crops from independent farms. The financial resources of agribusiness corporations has facilitated the transition to green revolution methods, enabling large investments in the research and development of new products. The corporations can also provide loans and cash to individual farmers, often as a part of contracts that leave farmers with little actual control over which crops are grown and what methods are used.

agribusiness the business of farming conducted by large-

While green revolution agriculture provides a wide variety of food at low prices for North Americans, the shift to these production methods has depressed local economies and created social problems in many rural areas. Communities in places such as the Great Plains of both Canada and the United States were once made up of farming families with similar middle-

Food Production and Sustainability Can green revolution agriculture like that practiced by successful North American corn farmers persist over time? Many modern strategies to increase yields, including the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, can have negative impacts. These methods can threaten the health of farm workers and nearby residents, pollute nearby streams and lakes, and even affect distant coastal areas. Some irrigation methods can deplete scarce water resources and reduce soil fertility over time. In addition, many North American farming areas have lost as much as one-

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Organically Grown

Throughout North America, there is a burgeoning revival of small family farms that supply organically grown (produced without chemical fertilizers, herbicides, or pesticides) vegetables and fruits and grass-

organically grown products produced without chemical fertilizers and pesticides

Sustainable food production may cause a decrease in harmful impacts on the environment as farms shift to organic methods and consumers learn the advantages of paying more for higher-

Recently, researchers have been studying the long-

There is growing concern about the raising of animals in “factory farms” in which cows, pigs, or poultry are raised in crowded conditions and fed chemicals to make them gain weight. As with other forms of chemically intensive agriculture, the most well-

Critics of these food production systems often argue that the government subsidies currently being given to farmers should be used as a tool for reform. They advocate directing subsidies away from factory farms and large-

VIGNETTE

The flip side of this story of the decline in North America of the family farm way of life is represented by the burgeoning prosperity of farmers like 37-

How can this be? In 2007, the rising price of petroleum products spurred the U.S. government to require that ethanol made from corn be added to gasoline in order to lower dependency on foreign energy sources. Now more than one-

Changing Transportation Networks and the North American Economy

An extensive network of road and air transportation that enables the high-

After World War II, air transportation also enabled economic growth in North America. The primary niche of air transportation is business travel, because face-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development Globalization has transformed economic development in North America, reorienting employment toward knowledge-

intensive jobs that require education and training. Most of the manufacturing jobs upon which the region’s middle class was built have either been moved abroad to take advantage of cheaper labor or have been replaced by technology. North America’s demand for imported goods and its export of manufacturing jobs helps make it a major engine of globalization. North America’s advantageous position in the global economy is a reflection of its size, technological sophistication, and geopolitical influence—

all of which enable it to mold the pro- globalization free trade policies that suit the major corporations of North America. The major long-

term goal of NAFTA is to increase the amount of trade between Canada, the United States, and Mexico. NAFTA is currently the world’s largest trading bloc in terms of the GDP of its member states. Flows of trade and investment between North America and Asia have increased dramatically in recent decades.

By the early 2000s, globalization was resulting in the offshore outsourcing of hundreds of thousands of information technology (IT) jobs.

North American farms have become highly mechanized, chemically intensive operations that need few workers but require huge amounts of land to be profitable.

In the twentieth century, the mass production of inexpensive automobiles and trucks, as well as the Interstate Highway System, fundamentally changed how people and goods move across the continent.