Fossil Fuel Exports

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 2

Globalization and Development: The vast fossil fuel resources of a few countries in this region have transformed economic development and driven globalization. In these countries, economies have become powerfully linked to global flows of money, resources, and people. Politics have also become globalized, with Europe and the United States strongly influencing many governments.

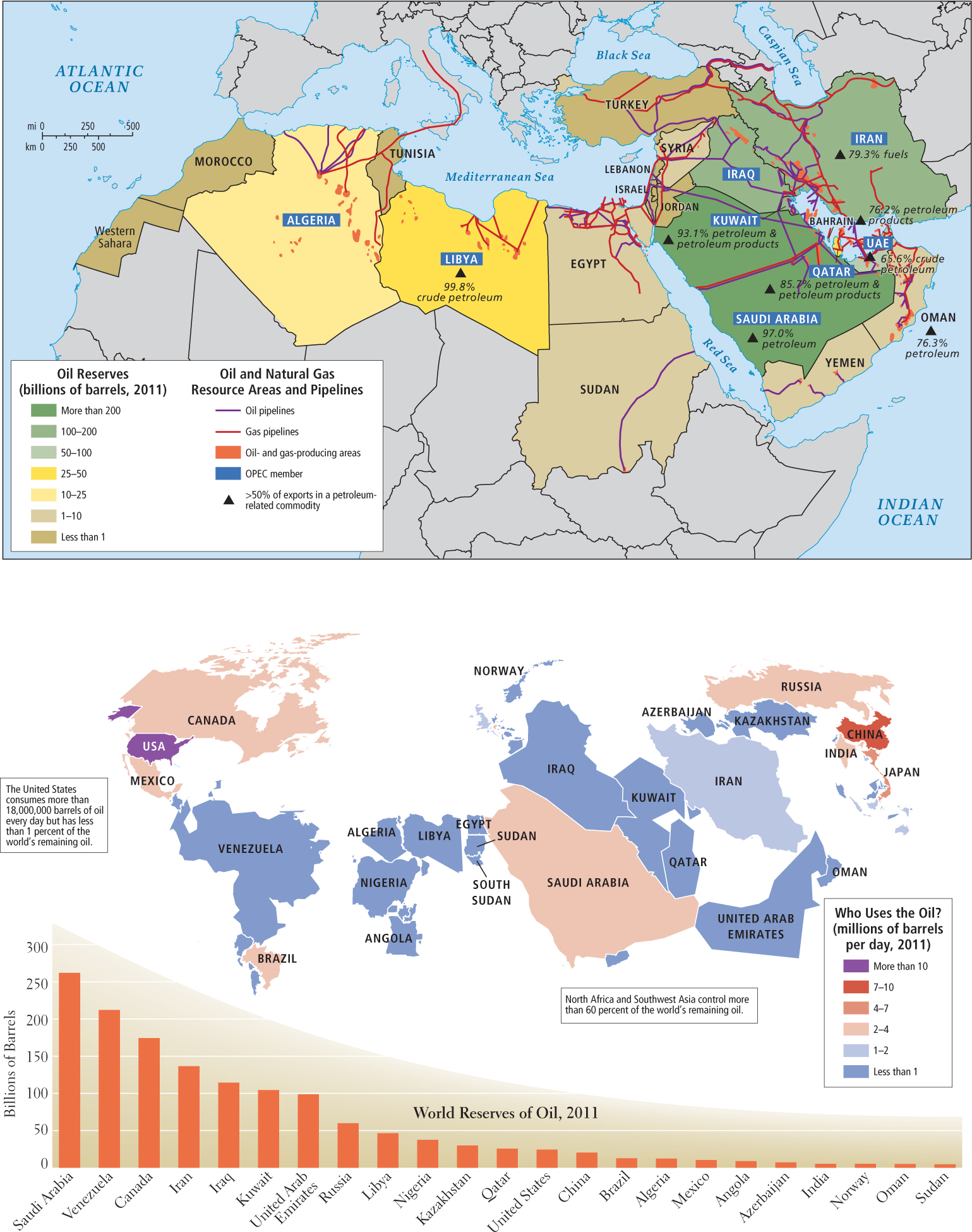

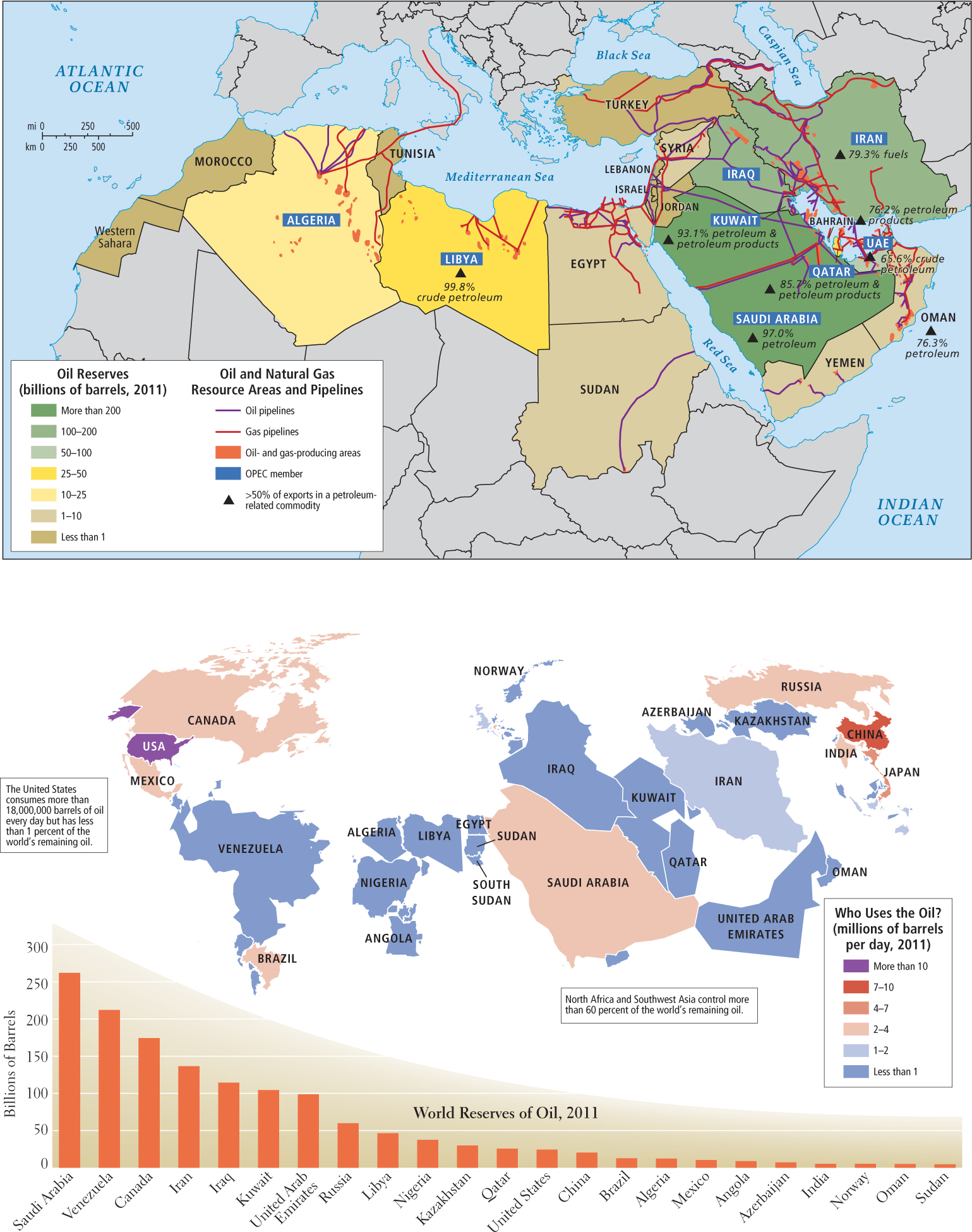

This region, which has two-thirds of the earth’s known reserves of oil and natural gas, is the major fossil fuel supplier to the world. Most oil and gas reserves are located around the Persian Gulf (Figure 6.18) in the countries of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iran, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The North African countries of Algeria, Libya, and Sudan also have oil and gas reserves. It is important to note, however, that several countries in this region—Morocco, Tunisia, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and Turkey—have minimal oil and gas resources or are net importers of fossil fuels. Meanwhile, Egypt and Sudan produce enough to supply most of their own needs, but export little. Regardless of their own petroleum resources, all countries in the region are affected by the geopolitics of oil and gas.

Figure 6.18: Economic issues: Oil and gas resources in North Africa and Southwest Asia. (A) The map shows the oil reserves, oil and gas resource areas, and pipelines in the region. (B) The graph shows the oil reserves by country; in the map, the size of countries corresponds to the amount of oil reserves held, and the color corresponds to the amount used.

European and North American companies were the first to exploit the region’s fossil fuel reserves early in the twentieth century. These companies paid governments a small royalty for the right to extract oil (natural gas was not widely exploited in this region until the 1960s, though gas extraction has grown rapidly since then). Oil was processed at on-site refineries owned by the foreign companies and sold at very low prices, primarily to Europe and the United States and eventually to other countries, such as Japan.

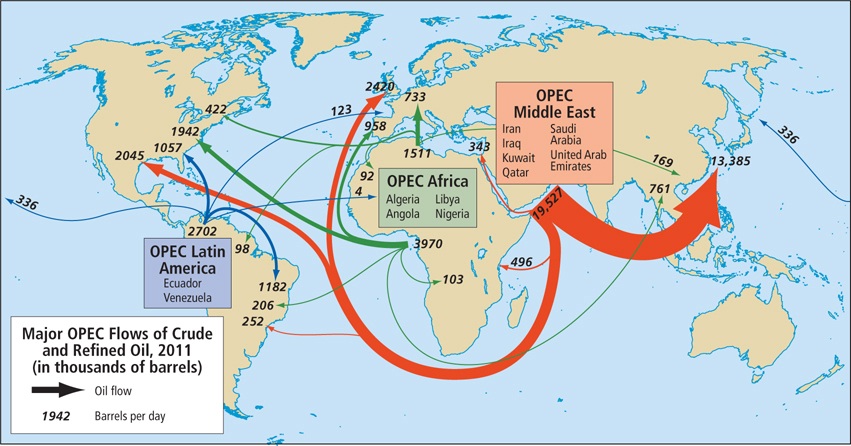

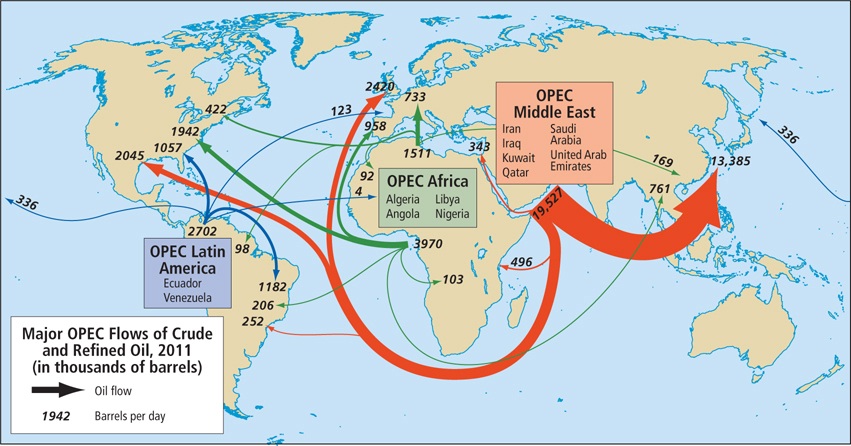

Global oil and gas prices have risen and fallen dramatically since 1973, when governments in the Gulf states raised the price of oil and gas for several reasons. For one, the Gulf states were imposing a kind of penalty in response to U.S. support for Israel in the 1973 Yom Kippur War between Israel and neighboring Arab countries (discussed further below). The oil-producing states were also reacting to a long-term trend of rising prices on products exported from European countries and the United States to the Gulf states. The oil price increase in 1973 was made possible by the founding in 1960 of a cartel—a group of producers strong enough to control production and set prices for products—known as OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries). For a few months after the Yom Kippur War, there was a total halt of oil shipments from the Gulf states to the United States and to a few other countries that supported Israel. When the Gulf states resumed their shipments, they raised the price of oil. OPEC remains the main organization of oil-producing states; membership, which changes from time to time, now includes all of the states indicated in Figure 6.19. OPEC members cooperate to periodically restrict or increase oil production, thereby significantly influencing the price of oil on world markets. A move to create an OPEC-like cartel for natural gas is currently underway.

Figure 6.19: Major OPEC oil flows in 2011. The map shows the average number of barrels (in thousands) of crude oil and petroleum products distributed per day by OPEC to regions of the world.

cartel a group of producers strong enough to control production and set prices for products

OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) a cartel of oil-producing countries—currently, Algeria, Angola, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Ecuador, and Venezuela—that was established to regulate the production and price of oil and natural gas

Page 250

Page 251

Many OPEC countries, which were exceedingly poor just 40 years ago, have become much wealthier since 1973, but they have also become more vulnerable to economic downturns. For example, oil income in Saudi Arabia shot up from U.S.$2.73 billion in 1971 to U.S.$110 billion in 1981, to U.S.$592.4 billion in 2012. But this wealth has not been widely shared within OPEC countries or within the region. The Gulf states were slow to invest their fossil fuel earnings in basic human resources at home, and they only gradually began to explore other economic strategies in case oil and gas ran out. Like their poorer neighbors, OPEC countries remain very dependent on the industrialized world for their technology, manufactured goods, skilled labor, and expertise.

Recently, the Gulf states have begun to invest heavily in roads, airports, new cities, irrigated agriculture, and petrochemical industries. Saudi Arabia is investing in six new cities in different parts of the country to spur investment and advance economic and social development. A good example of the scale of projects in the Gulf states is Palm Jumeirah (Palm Island) in Dubai, UAE (see Figure 6.24A), which is intended to be the centerpiece of Dubai’s planned tourism economy—insurance against the day when the regional oil economy fails for whatever reason. The recession that started in 2008 badly damaged the economies of the Gulf states. Most of the massive building projects that were underway, including Palm Island and similar projects in the UAE, screeched to a halt. The recession showed that Dubai’s tourism economy is highly vulnerable to economic downturns. It also affected remittances sent back to home countries because, with drastically fewer jobs available in the recession, those countries that have many temporary workers in the Gulf states have had a steep decline in remittances sent home.

Resources have been poured primarily into visible physical development; much less oil wealth has been invested in education, social services, public housing, and health care. Libya, before the Arab Spring, and Kuwait are exceptions to this pattern, having developed ambitious plans for addressing all social service needs, with especially heavy investment in higher education. Iran is another possible exception, though because the Iranian government shares very little of its data with the rest of the world, it is hard to be certain how much it is investing in social services. Meanwhile, the non-OPEC countries (those that do not produce fossil fuels) do not share directly in the wealth of the Persian Gulf states, and for the most part, the oil-rich countries have not helped their poorer neighbors develop.

Page 252

Many factors beyond OPEC’s control strongly influence world oil prices. Recent rapid industrialization in China and India has driven up their use of fuel and other petroleum products, creating long-term pressures that are raising the price of oil. Employing a theory known as “peak oil,” some experts argue that in an era of diminished oil reserves—which these experts say has already begun—prices will be driven higher. On the other hand, efforts to combat climate change with renewable energy sources have been increasingly successful and could dramatically reduce the demand for oil. Current global oil flows are summarized in Figure 6.19.

Economic Diversification and Growth

Greater economic diversification—expansion into a wider range of economic development strategies—could have a significant impact on the region, bringing economic growth and broader prosperity and thereby limiting the damage caused by a drop in the prices of oil, gas, or other commodities on the world market.

economic diversification the expansion of an economy to include a wider array of activities

By far the most diverse economy in the region is that of Israel, which has a large knowledge-based service economy and a particularly solid manufacturing base. Israel’s goods and services and the products of its modern agricultural sector are exported worldwide. Turkey is the next most diversified, in part because—like Israel—it has never had oil income to fall back on. Egypt, Morocco, Libya, and Tunisia are also starting to move into many new economic activities. Some fossil fuel–rich countries tried to diversify into other industries. This was true in Syria until the dictator Bashar al-Assad refused to respond to civil protests from an economically stressed citizenry, which precipitated a revolution. A somewhat more responsive government in the UAE developed an economy in which only 25 percent of GDP is based directly on fossil fuels, and where trade, tourism, manufacturing, and financial services are now dominant. Even so, most Gulf states are still very dependent on fossil fuel exports and the spin-off industries they generate.

Page 253

Diversification has also been limited by economic development policies that favored import substitution (see Chapter 3). Beginning in the 1950s, many governments, such as those of Turkey, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Syria, Jordan, Tunisia, and Libya, established state-owned enterprises to produce goods for local consumption. Among the major products were machinery and metal items, textiles, cement, processed food, paper, and printing. These enterprises were protected from foreign competition by tariffs and other trade barriers. With only small local markets to cater to, profitability was low and the goods were relatively expensive. Without competitors, the products tended to be shoddy and unsuitable for sale in the global marketplace. Meanwhile, the extension of government control into so many parts of the economy nurtured corruption and bribery and squelched entrepreneurialism. Many of the state-owned import substitution enterprises have subsequently either gone bankrupt or been sold to private investors.

Economic diversification and export growth were also limited by a lack of financing, private and public, from within the region. For example, rather than invest locally in mundane but needed consumer products, members of the Saudi royal family generally invest their wealth in more profitable private firms in Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia. Even when private and public investment has stayed in the region, it has gone into lavish projects, such as those in Dubai that give jobs to skilled Asians and may not necessarily prove to be economically profitable. Only recently have governments recognized that they need to invest locally in order to plan wisely for a time when oil and gas run out.

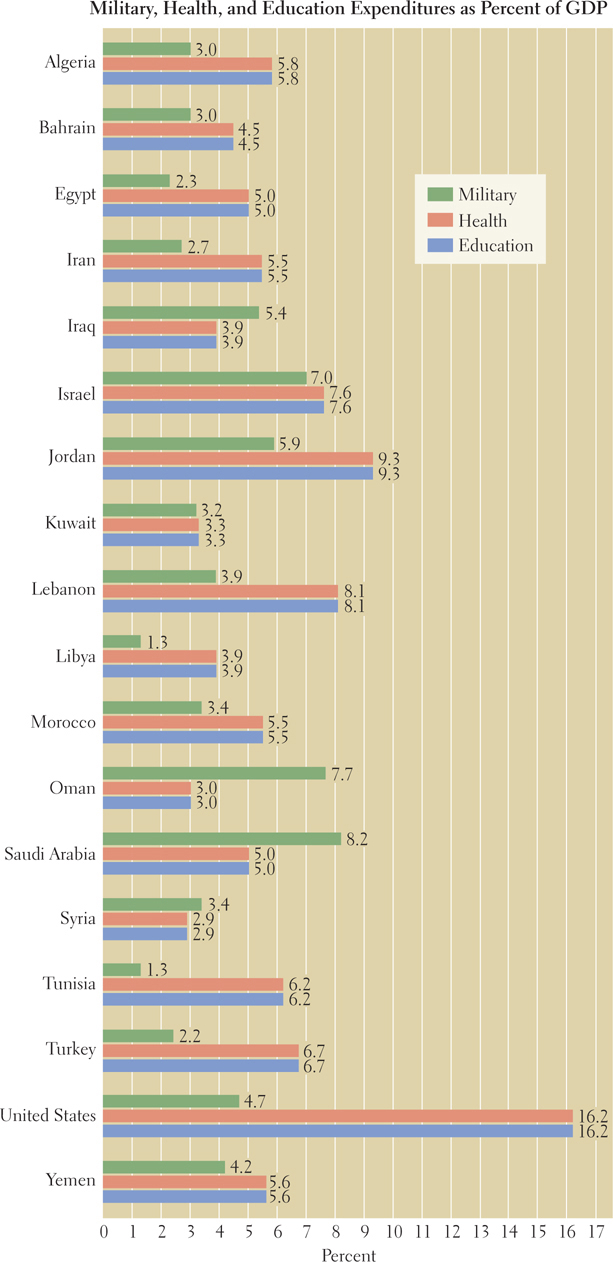

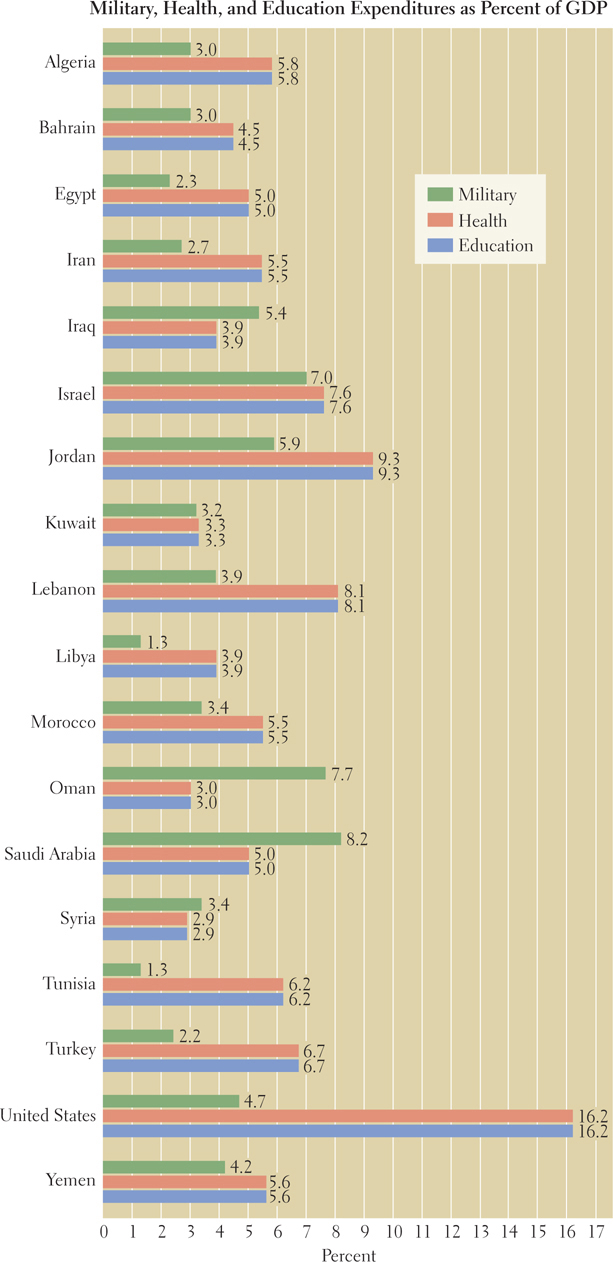

Finally, both international and domestic military conflicts and the ensuing political tensions have stymied economic diversification because they have resulted in some of the highest levels (proportionate to GDP) of military spending in the world. Military spending diverts funds from other types of development, such as health care and education (Figure 6.20). The top four spenders—Saudi Arabia, Oman, Israel, and Jordan—lead the world in military expenditures as a percentage of GDP, and the percentage in all countries in the region, except Tunisia and Libya, is above the global average of 2 percent.

Figure 6.20: Military, health, and education expenditures as a percent of GDP, 2008–2009. These graphs show those countries in the region that have data for each variable. Note that the data is from 2008–2009 and expenditures may have changed due to the Arab Spring. The United States is included for comparative purposes.

[Sources consulted: Human Development Report 2010, Table 15, and Human Development Report 2011, Table 10 (New York: United Nations Development Programme, 2010]

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Globalization and Development The vast fossil fuel resources of a few countries in this region have transformed economic development and driven globalization. In these countries, economies have become powerfully linked to global flows of money, resources, and people. Politics have also become globalized, with Europe and the United States strongly influencing many governments.

Profits in the oil- and gas-producing countries were low until OPEC initiated price increases in 1973. Since then, wealth has accrued mainly to a privileged few.

Until very recently, countries in the region, with the exception of Turkey and Israel, had not diversified their economies. In the Gulf states, huge profits have not been invested at home, but rather abroad, thus limiting diversification. When import substitution policies have been tried, they have failed to lift countries out of poverty.

Page 254