6.8 POPULATION AND GENDER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 5

Population and Gender: This region has the second-

Although fertility rates have dropped significantly since the 1960s, to 3.1 children per adult woman in 2012, they are still higher than the world average of 2.6. Only sub-

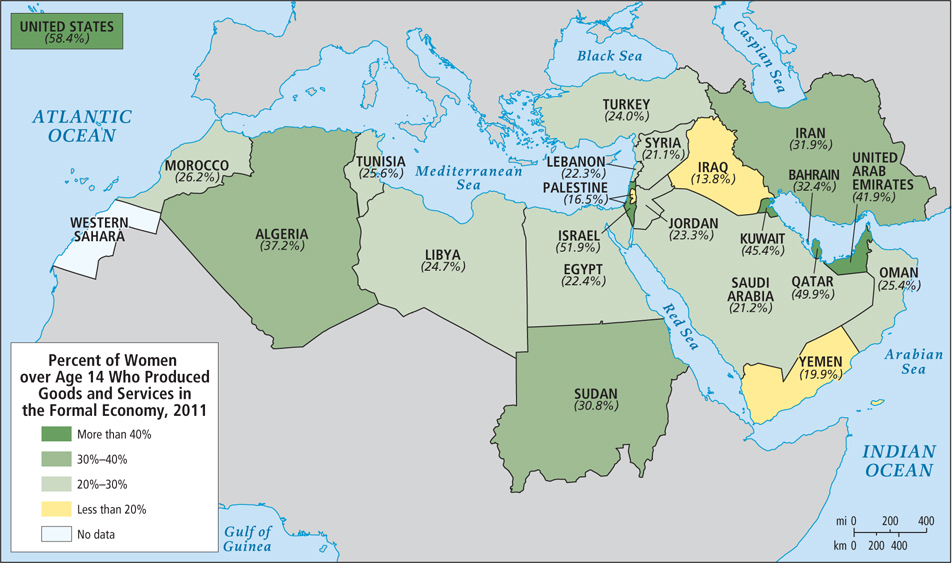

As noted in many world regions, population growth rates are higher in societies where women are not accorded basic human rights, are less educated, and work primarily inside the home. In places where women have opportunities to work or study outside the home, they usually choose to have fewer children. Figure 6.29 shows that as of 2011, considerably less than 50 percent of women across the region (except in Israel, Kuwait, and Qatar) worked outside the home at jobs other than farming. Moreover, on average only 74.8 percent of adult females can read—

For uneducated women who work only at home or in family agricultural plots, children remain the most important source of personal fulfillment, family involvement, and power. This may partially explain why in 2011 a good deal less than half of women in this region were using modern methods of contraception, and only 54 percent were using any method of contraception at all. Both of these numbers are well below the world average of 55 and 62 percent, respectively. Other factors resulting in low use of contraception are male dominance over reproductive decisions and the unavailability or high cost of effective birth control products.

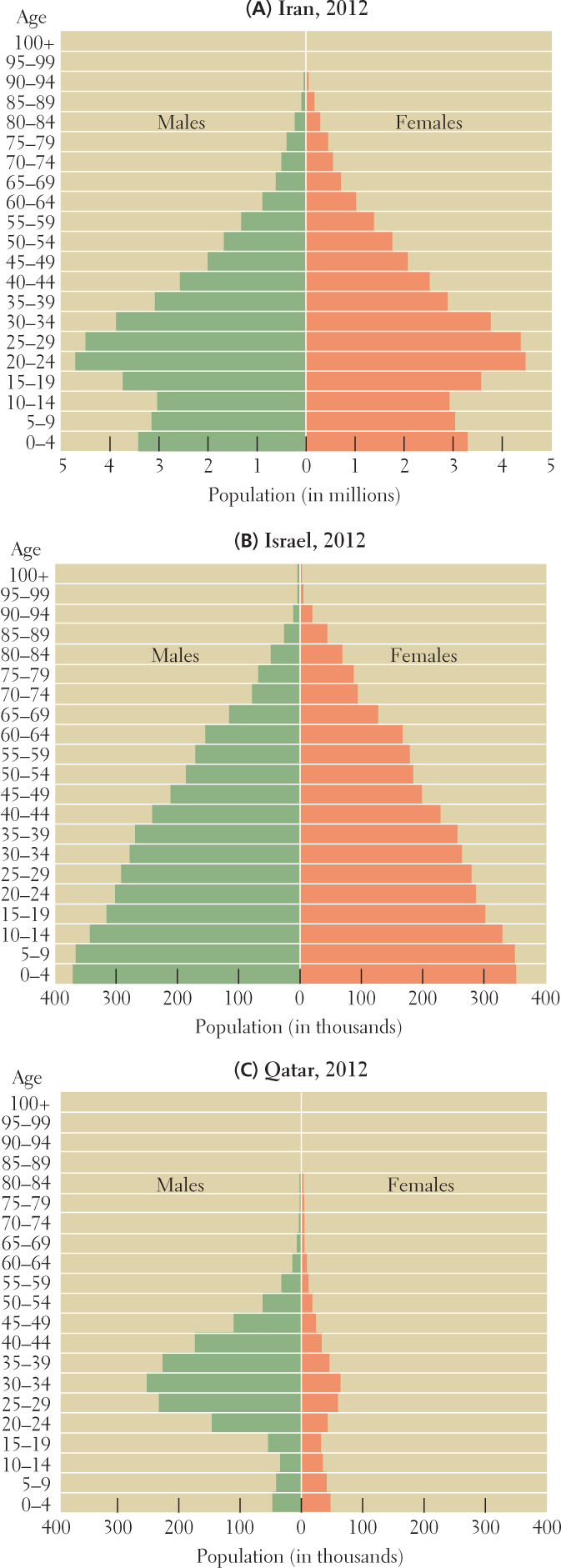

The deeply entrenched cultural preference for sons in this region is both a cause and a result of women’s lower social and economic standing. It also contributes to population growth, as families sometimes continue having children until they have a desired number of sons. Moreover, some young females may not survive because of malnutrition and associated illnesses or because female fetuses are sometimes aborted. The result is that males slightly outnumber females in several age cohorts of the population pyramids in Figure 6.25 (see also the discussion in Chapter 1). In Qatar and the UAE, gender imbalance is extreme (see Figure 6.25C); in these countries, the unusually large numbers of males over the age of 15 is the result of the presence of numerous male guest workers. Opportunities for women are opening and this change is likely to reduce women’s interest in having large families. Slower population growth will mean that fewer resources will have to be invested in housing, schools, and services (see “On the Bright Side”).

Changing Population Distribution

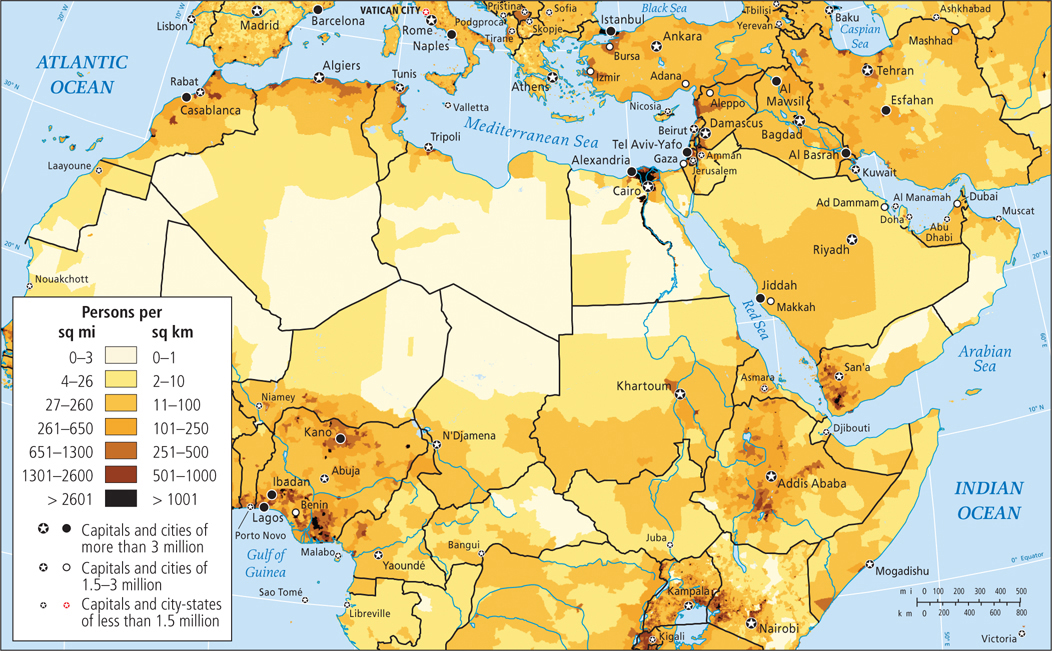

Although the region as a whole is nearly twice as large as the United States, most of the population is concentrated in the few areas that are useful for agriculture. Vast tracts of desert are virtually uninhabited, while the region’s 477 million people are packed into coastal zones, river valleys, and mountainous areas that capture orographic rainfall (compare Figure 6.26 with Figure 6.5). Population densities in these areas can be quite high. For example, some of Egypt’s urban neighborhoods have more than 260,000 people per square mile (100,000 people per square kilometer), a density 4 times higher than that of New York City, the densest city in the United States.

6.8.1 SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES

This section explores the broad social changes occurring in this region with regard to families, gender, and space. Like most institutions in this region, the family remains predominantly patriarchal. Related to this are divisions between the public spaces of society, which are usually occupied by men, and the private spaces of the home, where women spend most of their time. More legal limits are imposed on women here than in any other region, with various countries restricting women’s political freedoms, how they dress, and their ability to occupy public spaces. Change on these fronts is happening, as women push for more equitable treatment, but the pace is slow.

Families and Gender

The family is the most important institution in this region. Although the role of the family is changing, a person’s family is still such a large component of personal identity that the idea of individuality is almost a foreign concept. Each person is first and foremost part of a family, and the defining parameter of one’s role in the family is gender identity (see Figures 6.3 and 6.4, both of which accompany the opening vignette).

The head of the family is nearly always a man; even when a woman is widowed or divorced, she is under the tacit supervision of a male, perhaps her father, her adult son, or another male relative. An educated unmarried woman with a career outside the home is likely to live in the home of her parents or a brother and to defer to them out of respect in decision making. Traditionally, men are considered more stable and capable of making decisions and thus, it is thought that they should be in charge. Women usually agree or at least comply with minimal argument. These patriarchal ideas are beginning to change as the result of modernization. During the Arab Spring, a few brave women have challenged convention and taken a political stance (see the opening vignette; see also the discussion below).

patriarchal relating to a social organization in which the father is supreme in the clan or family

Gender Roles and Gendered Spaces

Carefully specified gender roles are common in many cultures, and there is often a spatial component to these roles. In the region of North Africa and Southwest Asia, in both rural and urban settings, the ideal is for men and boys to go forth into public spaces—the town square, shops, the market. Women are expected to inhabit primarily private spaces. But there are many possible exceptions to those ideals.

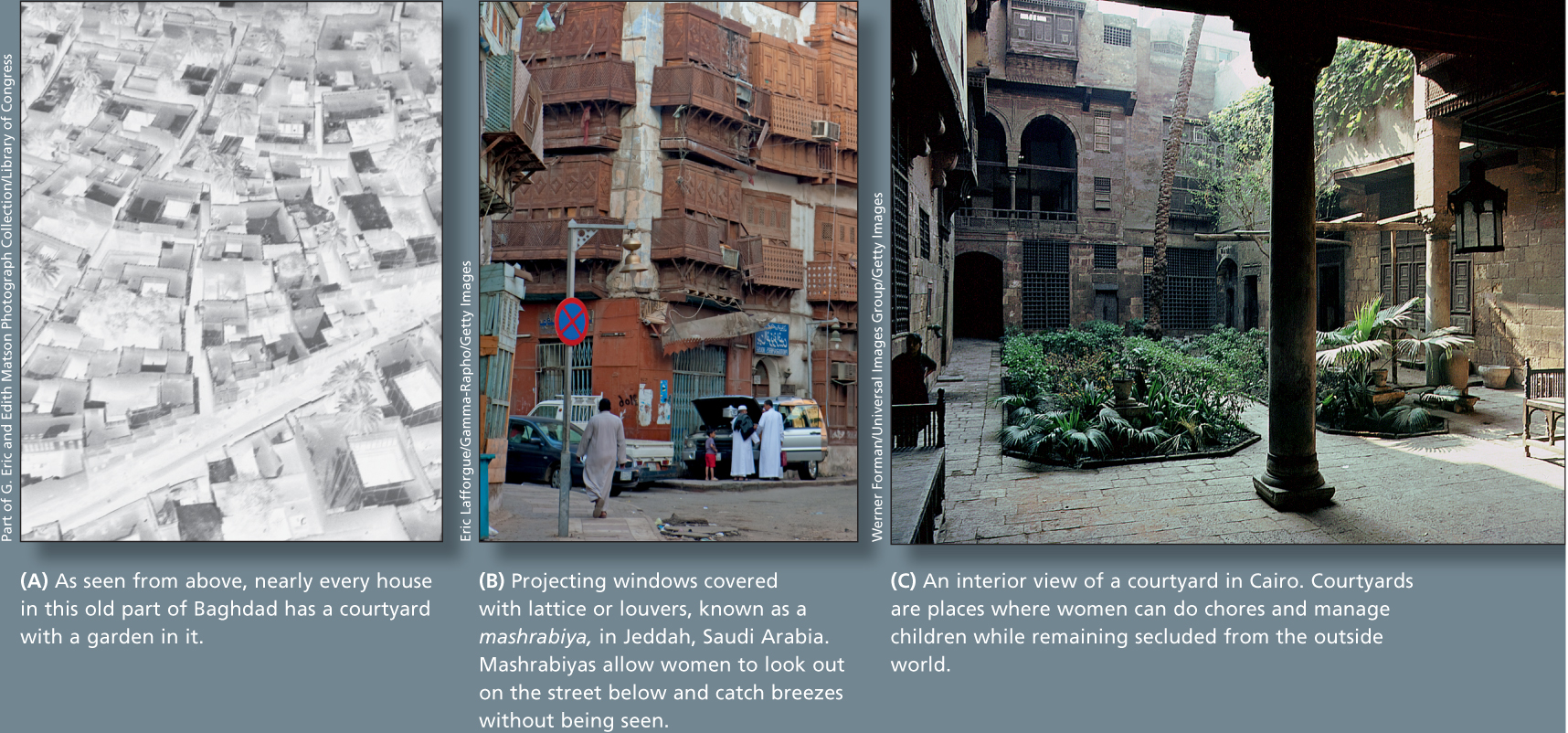

To facilitate this ideal of public/private spaces for the sexes, traditional family compounds included a courtyard that was usually a private, female space within the home (Figure 6.27A); the only men who could enter it were relatives. For the urban upper classes, female space was an upstairs set of rooms with latticework or shutters at the windows, which increased the interior ventilation and from which it was possible to look out at street life without being seen (see Figure 6.27B, C). Today, the majority of people in the region live in urban apartments, yet even in these there is a demarcation of public and private space. One or two formally furnished reception areas are reserved for nonfamily visitors, and rooms deeper into the dwelling are for family-

The requirement that women stay out of public view (also known as female seclusion) is most strictly enforced in the more conservative Muslim countries of the Gulf states (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates). Women in these countries are generally expected to remain in private spaces except when on important business; then they are to be accompanied by a male relative. In the more secular Islamic countries—

female seclusion the requirement that women stay out of public view

Gulf states Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates

Affluent urban women may observe seclusion either rarely (especially if they are highly educated), or, if they are relatively affluent but less educated, even more strictly than do rural women. Although rural women are often more traditional in their outlook, they have many tasks that they must perform outside the home: agricultural work, carrying water, gathering firewood, and buying or selling food in markets. Meanwhile, upper-

jihadists especially militant Islamists

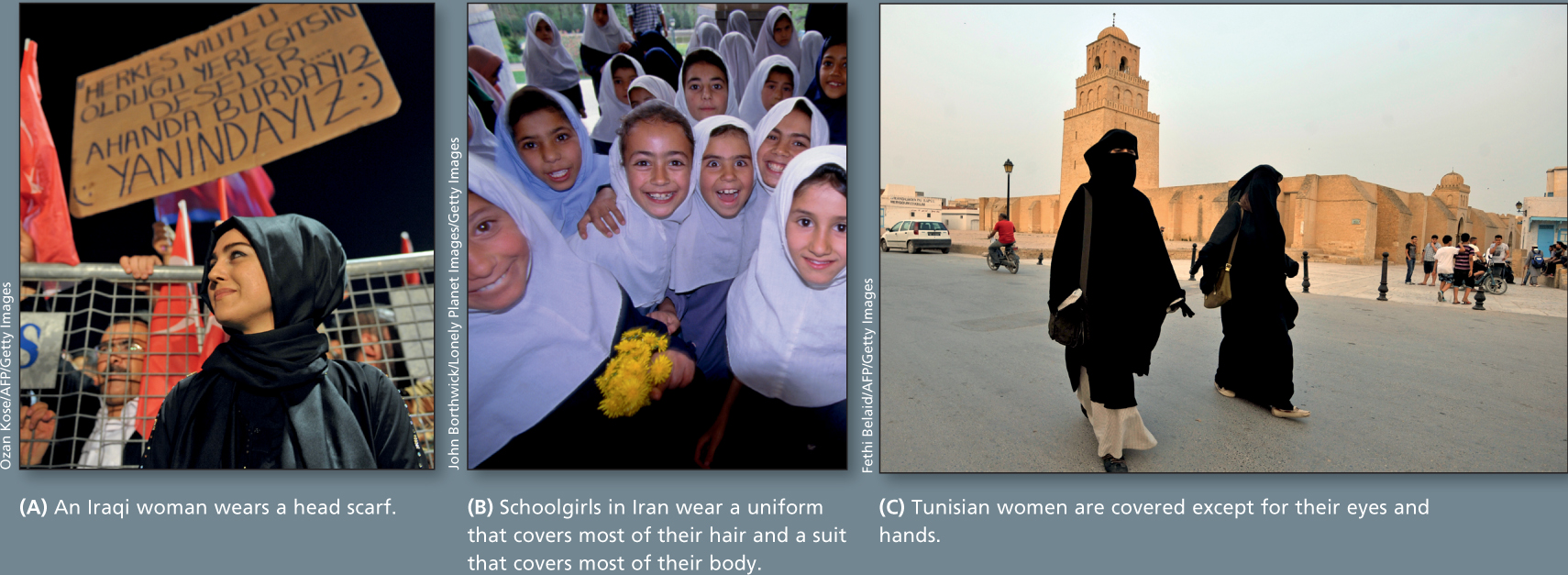

Many women in this region use clothing as a way to create private space (Figure 6.28). This is done with the many varieties of the veil, which may be a garment that totally covers the person’s body and face or just a scarf that covers the person’s hair. In some cultures, even prepubescent girls wear the veil; in others, they go unveiled until their transition into adulthood is observed. The veil allows a devout Muslim woman to preserve a measure of seclusion when she enters a public space, thus increasing the territory she may occupy with her honor preserved. A modern young woman may choose to wear a headscarf with jeans and a t-

veil the custom of covering the body with a loose dress and/or of covering the head—

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Question 6.20

Why do these women wear a veil, no matter what style of veil they choose?

There is considerable debate about the origin and validity of female seclusion and whether veiling and seclusion are specifically Muslim customs. Scholars say that these ideas, as well as the custom of having more than one wife, actually predate Islam by thousands of years and do not derive from the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad. In fact, Muhammad may have been reacting against such customs when he advocated equal treatment of males and females. Muhammad’s first wife, Khadija, did not practice seclusion, and worked as an independent businesswoman whose counsel Muhammad often sought.

The Rights of Women

This region has notably more restrictive customary and legal limits on women than any other. In the Gulf states, women cannot travel independently or even drive a car or shop without male supervision. Yet even here changes have recently been made. In the decade of the 2000s, some women in the Gulf states became more active in public life, education, and business. In Qatar, Sheikha Moza, the second of the three wives of the emir (Muslim ruler) of Qatar, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al-

The Arab Spring in North Africa demonstrated just how elusive political equality for women can be. In Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt, some women were active as public protesters against undemocratic regimes, but military and civilian supporters of the various regimes singled them out for particularly harsh retribution. Among their fellow male demonstrators, it was usually the younger men who supported the women’s rights and physically defended them when supporters of the various regimes attacked.

A source of contention within this region and abroad is the practice of polygyny (see Chapter 7): when a man takes more than one wife at a time. Although the Qur’an allows a man up to four wives, it generally does not encourage this and imposes financial limits on the practice by requiring that each wife be given separate and equal living quarters and support. While legal in most of the region (not Tunisia), polygyny is relatively rare, with less than 4 percent of males in North Africa practicing it. In Southwest Asia, polygyny—

Female genital mutilation (FGM, defined and discussed in Chapter 7) is not widely practiced in this region except in Egypt, where although it is illegal, as of 2013 according to the World Health Organization, more than 90 percent of women have undergone the practice, mostly before age 15.

Political and social equality with men can only improve with more economic independence for women (Figure 6.29). With the sole exception of Israel, women in this region generally do not work outside the home; when they do, they are paid, on average, only about 40 percent of what men earn for comparable work. Only India, Pakistan, and other South Asian countries have a similarly large wage gap based on gender.

The Lives of Children

Three observations can be made about the lives of children in the Islamic cultures of North Africa and Southwest Asia. First, in most families children contribute to the welfare of the family starting at a very young age. In cities, they run errands, clean the family compound, and care for younger siblings. In rural areas, they do all these chores and also tend grazing animals, fetch water, and tend gardens. Second, their daily lives take place overwhelmingly within the family circle. Both girls and boys spend their time within the family compound or in urban areas in adjacent family apartments. Their companions are adult female relatives and siblings and cousins of both sexes. Even teenage boys in most parts of the region identify more with family than with age peers.

In rural areas, prepubescent girls can move around in public space as they go about their chores in the village. After puberty they may be restricted to the family compound and required to wear the veil. The U.S. geographer Cindi Katz found that until puberty, rural Sudanese Muslim girls have considerably more spatial freedom than do girls of similar ages in the United States, who are rarely allowed to range alone through their own neighborhoods.

The third observation is that school, television, and the Internet increasingly influence the lives of children and introduce them to a wider world. Most children go to school; many boys go for a decade or more, and increasingly girls go for more than a few years; and in some countries (Algeria, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, the occupied Palestinian Territories, Oman, Qatar, Tunisia, and the UAE), a larger percentage of girls than boys go to school. Like educated women everywhere, these girls will make life choices different from those of their mothers.

Even in rural areas, it is fairly common for the poorest families to have access to a television, which is often on all day, in part because it provides a window on the world for secluded women. Television can serve either to reinforce traditional cultural values or as a vehicle for secular perspectives, depending on which channels are watched.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 5

Population and Gender This region has the second-

highest population growth rate in the world, after that of sub- Saharan Africa. Part of the reason for this is that women are generally poorly educated and tend not to work outside the home. Childbearing thus remains crucial to a woman’s status, a situation that encourages large families. The role and social standing of women in the region is one of the issues being addressed by current political movements. The family is the most important societal institution in the region.

Most Muslim families in this region are patriarchal in structure. The role and status of women, the spaces they occupy, and the clothes they wear are often carefully defined, circumscribed, and in some cases rigidly imposed.

146. EDUCATION, ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT ARE KEYS TO A BETTER LIFE FOR MUSLIM WOMEN

146. EDUCATION, ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT ARE KEYS TO A BETTER LIFE FOR MUSLIM WOMEN