8.8 POPULATION PATTERNS

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 5

Population and Gender: In this most densely populated of world regions, population growth is slowing as the demographic transition takes hold. Birth rates are falling due to rising incomes, urbanization, better access to health care, and the fact that women are finding more opportunities to study and work outside the home, and thus are delaying childbearing and having fewer children. However, a severe gender imbalance is developing in this region due to age-

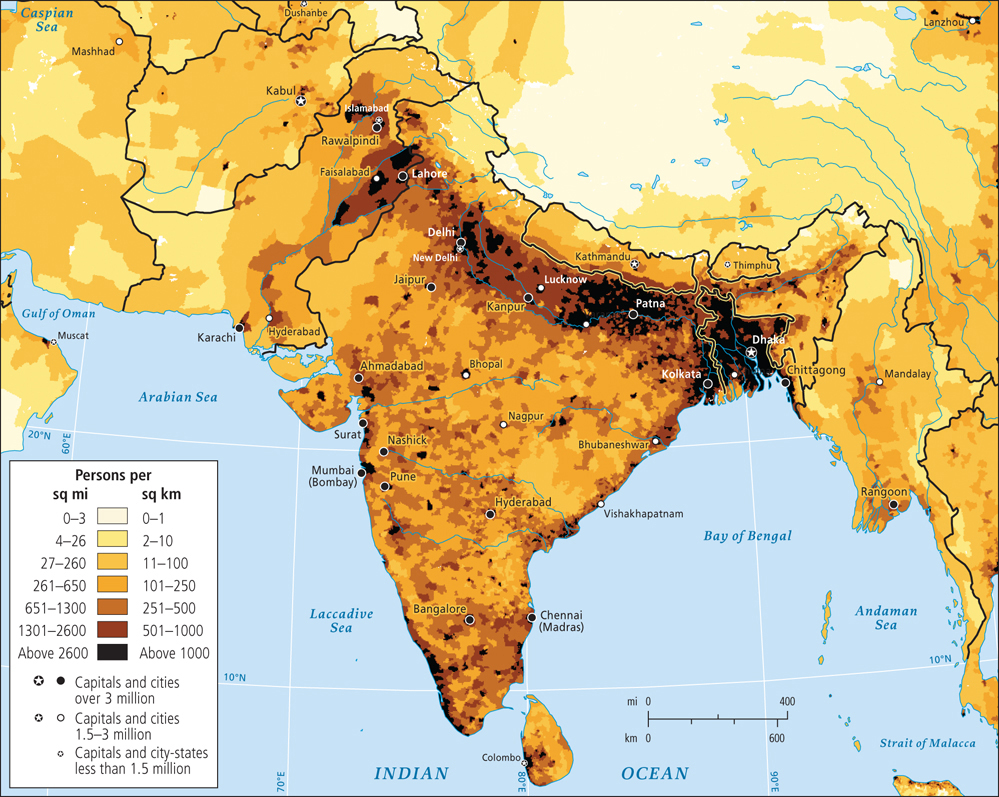

South Asia is the most densely populated region in the world (Figure 8.23; see also Figure 1.26). The region already has more people (1.68 billion) than China (1.35 billion), which has almost twice the land area of South Asia. With 1.46 billion people, India alone will have overtaken China’s 1.40 billion by 2025. By 2050, China’s population (if the one-

Population densities in this region are highest in the cities that lie just south of the Hindu Kush and Himalayas, and are at their peak in the Ganga-

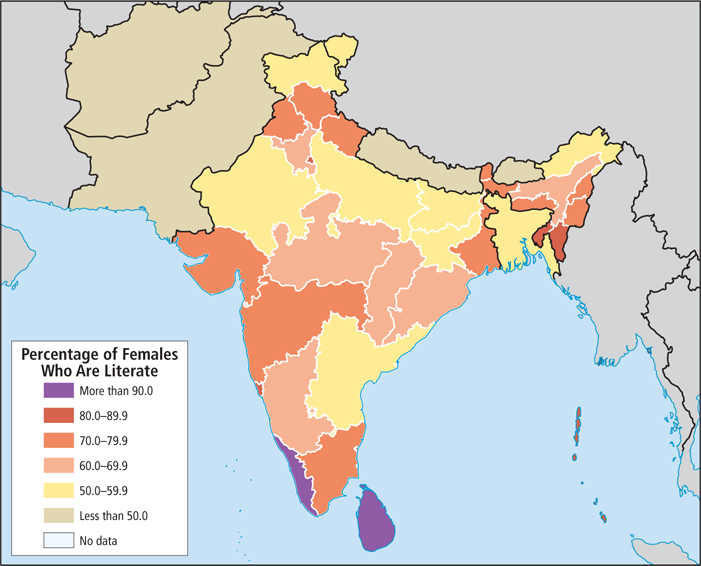

Geographic Patterns in the Status of Women On average, women’s literacy rates, social status, earning power, and welfare are generally lowest in the belt that stretches from the northwest in Afghanistan across Pakistan, western India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Ganga Plain into Bangladesh. Women fare somewhat better in eastern and central India and considerably better in southern India and in Sri Lanka. In these latter regions, where literacy rates are higher (Figure 8.25), different marriage, inheritance, and religious practices give women better access to education and resources.

Slowing Population Growth: Health Care, Urbanization, and Gender Efforts to slow population growth through better health care have been underway for more than 50 years. Today, urbanization and the rising status of women are helping to reduce the birth rate.

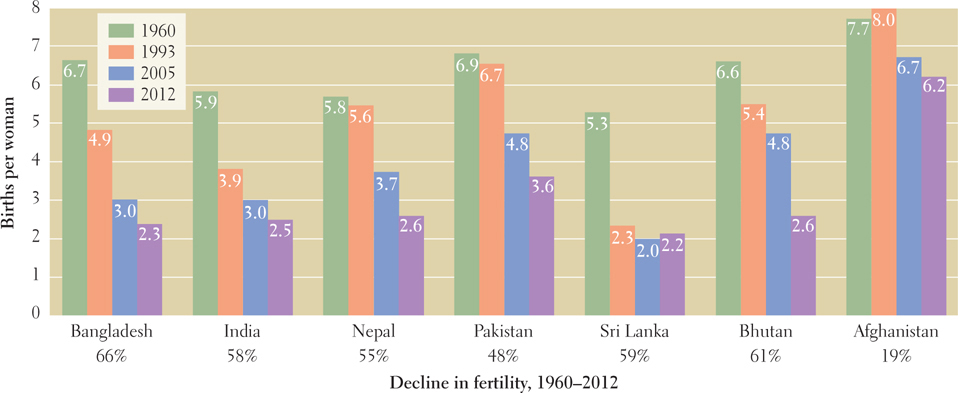

With improved health care—

At the same time that improved access to health care has helped propel the reduction in family size, the shift in population from rural to urban areas has reduced the economic incentive for having a large family (see the Figure 8.21 map). Whereas children in rural areas (starting at an early age) contribute their labor to farming, thus increasing the family income, the labor of children in urban areas is less likely to boost the family income. Children in urban areas are more likely to go to school, and thus represent a cost to the family for school fees, books, and uniforms.

Improvements in the status of women have also slowed population growth. As in other parts of the world, women in South Asia who have the opportunity to go to school and/or to work at a paying job tend to delay childbearing and have fewer children.

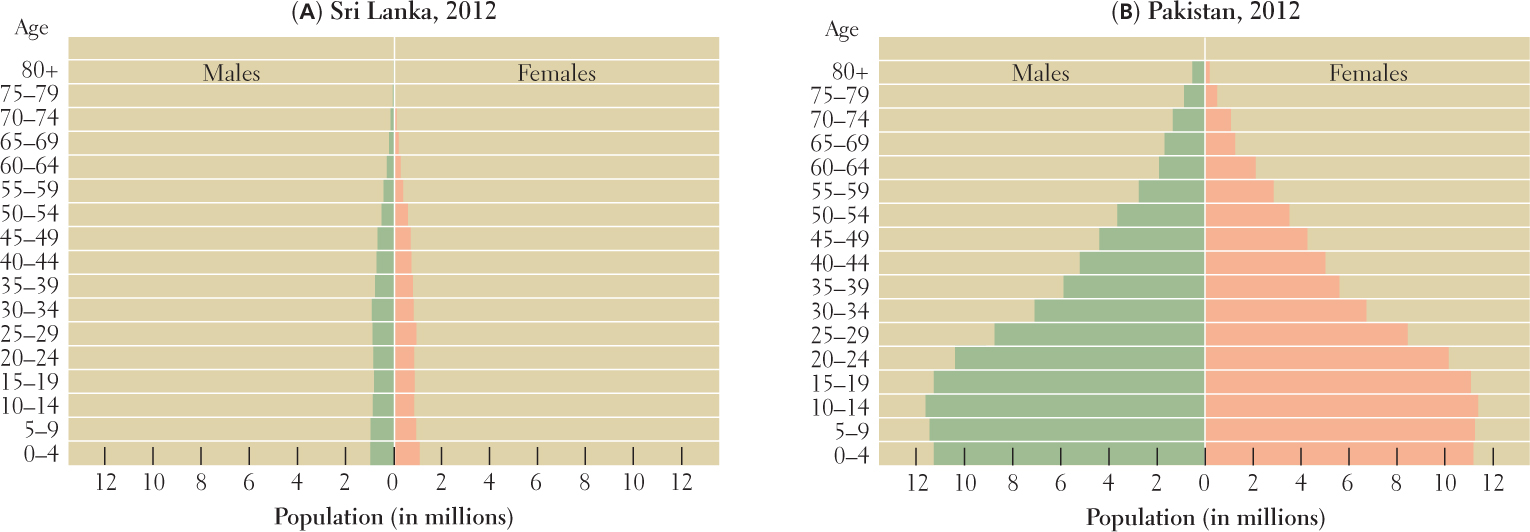

A comparison of the population pyramids as well as some other statistics for Sri Lanka and Pakistan helps illustrate the influence of health care and the status of women on birth rates (Figure 8.26; see also Figure 8.24 and Figure 8.25). As a country that is far along but not completely through the demographic transition (see Figure 1.28), Sri Lanka has a much higher GNI per capita (U.S.$4943) than Pakistan (U.S.$2550). Health care is generally better in Sri Lanka, as indicated by its much lower infant mortality rate (in 2012, Sri Lanka had 12 deaths per 1000 live births versus Pakistan’s 68 per 1000). Sri Lanka has also worked harder to educate and economically empower its women. Three key indicators of women’s education and empowerment that are associated with reduced fertility rates are much higher in Sri Lanka than in Pakistan: female literacy (90 percent versus 30 percent), the percentage of young women who attend high school (89 percent versus 19 percent), and the percentage of women who work outside the home (36 percent versus 16 percent). Surprisingly, Sri Lanka has achieved all this with an urbanization rate of just 15 percent, far lower than that of Pakistan’s 35 percent.

Despite Pakistan’s rather dismal statistics compared to those of Sri Lanka, its population pyramid does indicate that birth rates have slowed significantly (notice that the bottom of the pyramid in Figure 8.26B narrows noticeably). If this trend continues, Pakistan, as well as all South Asian countries except Afghanistan, will enjoy what is called the demographic dividend: a bulge of young people entering the workforce and choosing to have fewer children, who will thus have the time and energy to study, work, and contribute to the economy and civil society. Down the road, however, South Asian countries that have had a demographic dividend will have to deal with an aging population for which there will be far fewer younger caregivers and taxpayers to support the elderly.  185. CHILD LABOR PERSISTS IN INDIA DESPITE NEW LAWS

185. CHILD LABOR PERSISTS IN INDIA DESPITE NEW LAWS

Gender Imbalance South Asian populations have a significant gender imbalance because of cultural customs that make sons more likely than daughters to contribute to a family’s wealth. A popular toast to a new bride is “May you be the mother of a hundred sons.” Many middle- 186. GIRLS PAY THE PRICE FOR INDIA’S PREFERENCE FOR BOYS

186. GIRLS PAY THE PRICE FOR INDIA’S PREFERENCE FOR BOYS

Gender imbalance of the magnitude India is facing could create serious problems, such as surges in crime and drug abuse related to the presence of so many young men with no prospect of having a family. In all cultures, the possibility of having a family is a stabilizing influence for young men. The efforts of the state of Kerala to overcome gender imbalance by paying more attention to women’s development are worth watching. Kerala’s government has made women’s development a priority, funding education for women well beyond basic levels. The results are reflected in its female literacy rate, which is the highest in India at 87.8 percent (the average for India as a whole is 54.5 percent; see Figure 8.25 for the female literacy map), and in the number of women who work outside the home. In Kerala, far from being viewed as an economic liability to the family, daughters are seen as an asset. Women can travel the public streets alone and in groups and commonly work in public places, many in high positions in government, education, health care, IT industries, and other professions.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 5

Population and Gender In this most densely populated of world regions, population growth is slowing as the demographic transition takes hold. Birth rates are falling due to rising incomes, urbanization, better access to health care, and the fact that women are finding more opportunities to study and work outside the home, and thus are delaying childbearing and having fewer children. However, a severe gender imbalance is developing in this region due to age-

old beliefs that males are more useful to families than are females. As a result, adult males significantly outnumber adult females. There is a geographic pattern to the status of women, especially with regard to their literacy and earning power. Generally speaking, women are less restricted in the southern and eastern sections of this region.

While population growth is slowing across the region, momentum provided by a young population means that growth will continue for the foreseeable future.