9.7 URBANIZATION

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 4

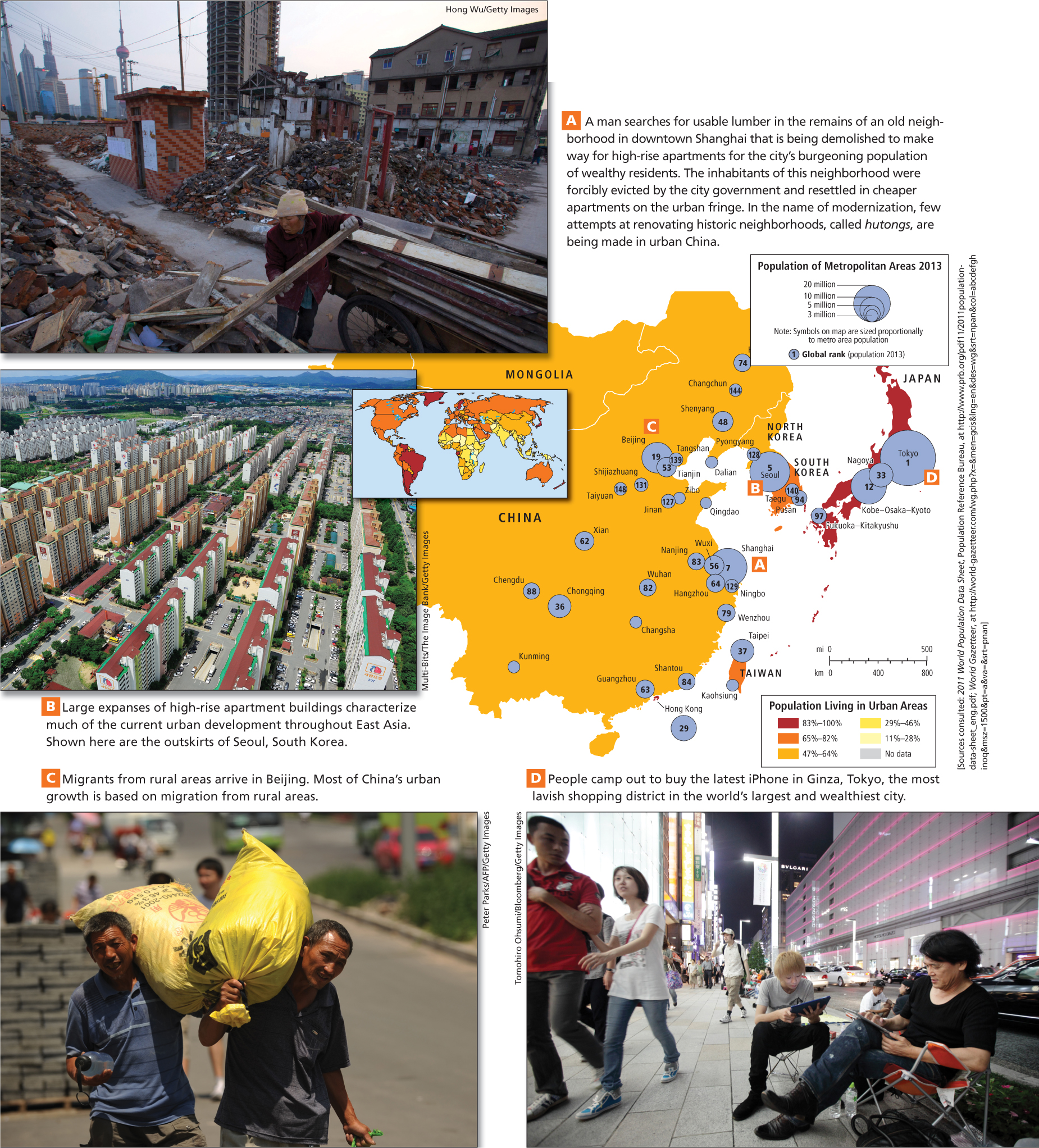

Urbanization: Across East Asia, cities have grown rapidly over the last century, fueled by export-

Throughout most of the twentieth century, the most dynamic East Asian cities were in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Tokyo, Japan, is the world’s largest urban area, with 34 million inhabitants. The vast Kobe–

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 9.17

A What happened to many of the former residents of Pudong, the new financial center of Shanghai?

Question 9.18

C Migrants to urban areas who ignore the hukou system are considered part of what population?

Question 9.19

D The urbanized region that stretches from the cities of Tokyo and Yokohama on Honshu south through the coastal zones of the Inland Sea to the islands of Shikoku and Kyushu is home to what percent of Japan’s population?

However, for the last 30 years, the strongest urban growth in East Asia, and indeed in the entire world, has been in China. In 2012, nineteen of the 20 fastest-

Spatial Disparities China’s focus on export-

International Trade and Special Economic Zones When China initiated economic reforms in the 1980s, many people were wary of the disruption that could result from abruptly opening the economy to international trade. To ease the transition, China first selected 5 coastal cities as sites where foreign technology and management could be imported to China and free trade established. These special economic zones (SEZs) (Figure 9.21) now operate like EPZs found in other world regions (see Chapter 3). In the late 1990s, the program was expanded to 32 other cities, many of them in the interior. These new locations were designated economic and technology development zones (ETDZs). Like SEZs, the ETDZs provide footholds for international investors and multinational companies eager to establish operations in the country.

special economic zones (SEZs) free trade zones within China, which are commonly called export processing zones (EPZs) elsewhere

This program was successful. Today the SEZs and ETDZs are China’s greatest growth poles, meaning that their development, like a magnet, is drawing yet more investment and migration. The first coastal SEZs were spectacularly successful. In just 25 years, many coastal cities, including Dongguan (the city Li Xia migrated to in the vignette that opens this chapter), grew from medium-

growth poles zones of development whose success draws more investment and migration to a region

Transportation Improvements

Recently, ETDZs in the interior have had higher rates of growth than those on the coast. One reason for this is that China spends 9 percent of its GDP on transportation improvements (by comparison, the United States spends 2 to 3 percent), which has made central and western China more accessible. New highways and railroads may eventually enable the interior to catch up with the economic development of the coast. The world’s longest high-

Urban Labor Shortages, Hukou System Reform, and Economic Transitions In 2013, China reached a major milestone that every rapidly developing country eventually reaches: its booming service sector now creates more jobs than its industrial sector. Many of these jobs offer much better pay and working conditions than industrial jobs do, which is creating a serious shortage of workers in the industrial sector.

Until recently, China’s spectacular urban growth was based on hundreds of millions of new urban migrants who were willing to put up with adverse conditions to earn a little cash. Fewer migrants are now willing to work in such jobs, creating periodic labor shortages. Some factory owners have been forced to offer higher pay, better working conditions, and shorter workdays or more time off. The government is also trying to offset labor shortages by making changes to the hukou system that will gradually give formal urban residency status to the vast floating population of people who have migrated illegally.

The extra costs these changes impose—

Some industrial employers hope that enough new migrants will be drawn to the cities by the hukou reforms that the labor shortages will disappear. The experiences of other countries, though, suggests that China’s urban service sector will continue to attract more and more migrants. The rapid growth of the service sector is being fueled by the purchasing power and consumption of China’s increasingly wealthy urban populations.

These changes in China’s labor market added a new twist to the story of Li Xia, whom we met in the vignette that opens this chapter.

VIGNETTE

Li Xia and her sister returned home to rural Sichuan a second time in 2006. With the money she had saved from her second job in Dongguan, Xia tried to open a bar in the front room of her parents’ house. She hoped to introduce the popular custom of karaoke singing she had enjoyed in the city, but people in her village could not stand the noise, and family tensions rose.

In early 2007, news that training was now available in Dongguan for skilled electronics assemblers convinced Xia to try the city again. Past experience with the bureaucracy and her knowledge of Dongguan helped Xia to sign up for the electronics training. The cost of tuition came out of her wages, which were only U.S.$350 a month rather than the U.S.$400 she had thought she would be paid. But this still left her with enough to live on, even after she sent money home.

In November of 2008, Xia heard rumors that a global recession was causing orders for electronics to be cut and that she might soon be laid off. But her factory limped along with a reduced staff. Then, miraculously, in June of 2009, orders picked up. Consumers in America had continued to buy electronics even as they downsized their homes and cars.

By 2011, Dongguan’s export industries were once again struggling to meet orders, and this time their main obstacle was a shortage of labor. The cost of living in Dongguan had risen quickly, and not enough employers in the industrial sector were willing to raise wages accordingly. Some migrant workers were returning to their homes in the interior provinces, where the lower cost of living was more in line with the lower wages. Others were staying in the cities to take advantage of new legal residency status granted to some Dongguan workers as part of the hukou reforms. Among those who stayed, many were finding better-

Hong Kong’s Special Role

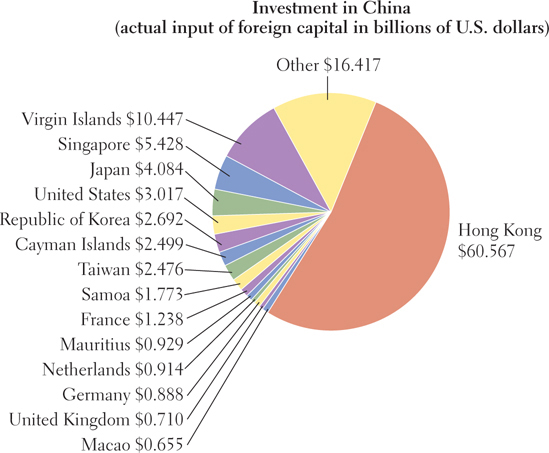

Hong Kong, which was a British possession from the end of the first Opium War in 1842 until 1997, has long had a special role as a link to the global economy for China. Before 1997, some 60 percent of foreign investment in China was funneled through Hong Kong, and since then Hong Kong has remained the financial hub for China’s booming southeastern coast (Figure 9.22).

Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated cities in the world; its 7.2 million people are packed into only 23 square miles (60 square kilometers), an area roughly the same size as the borough of Manhattan in New York City but with four times as many people. Hong Kong is also one of the richest cities in the world: its per capita GNI (adjusted for PPP) in 2013 was similar to that of the United States, at U.S.$53,050. Hong Kong also has the world’s third-

In July 1997, Britain’s 99- 220. AS HONG KONG ENTERS SECOND DECADE UNDER CHINA, CITY PONDERS PLACE IN ECONOMIC GIANT

220. AS HONG KONG ENTERS SECOND DECADE UNDER CHINA, CITY PONDERS PLACE IN ECONOMIC GIANT

Shanghai’s Latest Transformation Shanghai has historically been a trendsetting city. Its opening to Western trade in the early nineteenth century spawned a period of phenomenal economic growth and cultural development that led to it being called the “Paris of the East.” As a result of China’s recent reentry into the global economy, Shanghai is undergoing another boom, which has enriched some people and dislocated others (see Figure 9.20A). On average, residents of Shanghai are now as affluent as people in Central European countries like Poland and Hungary, and if current growth trends continue, their wealth will soon be on par with that of residents of Portugal or Slovenia. Shanghai today has the world’s busiest cargo port, and the region around the city is now responsible for as much as a quarter of China’s GDP.

In less than a decade, the city’s urban landscape has been remade by the construction of more than a thousand business and residential skyscrapers; subway lines and stations; highway overpasses; bridges; and tunnels. Shanghai’s shopping district on Nanjing Road is as imposing as any such district around the world. For hundreds of miles into the countryside, suburban development linked to Shanghai’s economic boom is gobbling up farmland, and displaced farmers have rioted.

Pudong, the city’s new financial center, sits across the Huangpu River from the Bund—

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 4

Urbanization Across East Asia, cities have grown rapidly over the last century, fueled by export-

oriented manufacturing industries. China has recently undergone the most massive and rapid urbanization in the history of the world. Its urban population, now more than 720 million people, has tripled since China initiated economic reforms in the 1980s. China’s focus on export-

oriented manufacturing based in urban areas has led to rural areas lagging behind cities in access to jobs and income, education, and medical care. China’s SEZs and ETDZs have been spectacularly successful, becoming major growth poles that draw investment and migration.

In 2013, China reached a major milestone that every rapidly developing country eventually reaches: its booming service sector now creates more jobs than its industrial sector.

A British possession from the end of the first Opium War in 1842 until 1997, Hong Kong has long had a special role as a link to the global economy for China.

Shanghai today has the world’s busiest cargo port, and the region around the city is now responsible for as much as a quarter of China’s GDP.