4.3 Researching Treatment

Let’s say that your interest in depression that follows breakups, plus your experiences at the counseling center helping students like Carlos, have led you to develop a new short-term treatment. In this treatment, which you have named “grief box therapy,” you encourage patients to create “grief boxes”—boxes into which they place reminders of their recently ended relationships and objects that symbolize their feelings of loss and hopelessness. You—and others—will want to know whether your treatment is effective; is using grief boxes better for treating depression (specifically the sort following a breakup) than doing nothing? Is it better than other treatments?

Research on treatment has challenges above and beyond those we’ve already discussed for research on psychopathology. And such research faces different challenges, depending on whether the target of treatment is neurological, psychological, or social factors.

Researching Treatments That Target Neurological Factors

Researchers and clinicians want to answer several questions when a new medication is developed, when an existing medication is used in a new way (to treat different symptoms), or when a new biomedical procedure is developed:

- Is the new treatment more effective than no treatment?

- If a treatment is effective, is it because of its actual properties (such as a medication’s particular ingredients) or because of patients’ expectations about what the treatment will do?

- Is the treatment more effective than other treatments currently used for those symptoms or problems?

- What are the treatment’s side effects, and are they troubling enough that patients tend to stop the treatment? How does this dropout rate compare to that for the other treatments?

To assess a treatment, researchers first need to determine what specific variables should be measured and to define what it means to be “effective.” Research on treatment frequently relies on an experimental or quasi-experimental design; in such studies, the independent variables might be the type of treatment, a specific technique, or type or dose of medication. And the dependent variables (the things measured) might be any of several variables, such as neural activity, specific mental contents, behavior, or family functioning. These variables are often related to the symptoms listed in the DSM-5 criteria for the disorder under investigation.

Drug Effect or Placebo Effect?

One way to determine whether a treatment is effective is to compare it to no treatment. If people receiving the treatment are better off than those who don’t receive any treatment, the treatment may have made the difference. But perhaps patients improve after taking a medication not because of the properties of the medication itself but because they expect to improve after taking it. In fact, many studies have confirmed that expecting a treatment to be helpful leads to improvement, even if the patients don’t receive any actual treatment (Colloca & Miller, 2011; Kirsch, 2010; Kirsch & Lynn, 1999).

Placebo effect A positive effect of a medically inert substance or procedure.

The best way to discover whether a medication is effective is to give a group of participants a placebo, an inert substance or a procedure that itself has no direct medical value. Often, a placebo is simply a sugar pill. A positive effect of such a medically inert substance or procedure is called a placebo effect. If patients who are given a sugar pill show the same improvement as patients who are given the pill with active ingredients, then a researcher can infer that the medication itself is not effective and that its apparent benefit is a result of the placebo effect.

The fact that people who suffer from certain disorders, including depression, sometimes improve following a placebo treatment (Kirsch, 2010; Kirsch et al., 2002) does not mean that their problem was imaginary or that they should throw away their medication. Rather, it seems that—for some people and for some disorders—the hope and positive expectations that go along with taking a medication (or undergoing a procedure) allow the body to mobilize its own resources to function better (Benedetti, 2009, 2010; Kirsch & Lynn, 1999; Scott et al., 2008).

Dropouts

Attrition The reduction in the number of participants during a research study.

On average, more than half of those who begin a treatment that is part of a research study do not complete the treatment—they drop out of the study (Kazdin, 1994; West, 2009); this reduction in the number of research participants during a study is called attrition. When attrition in a research study is different for different demographic groups (such as men versus women, younger people versus older ones, or people of different races), researchers can’t easily draw definitive conclusions about how well the treatment would have worked for members of all the groups (Kendall et al., 2004; Lambert & Ogles, 2004).

Researching Treatments That Target Psychological Factors

Many of the research issues that arise with biomedical treatments also arise in research on treatments that target psychological factors. In addition, as shown in TABLE 4.3, research on treatments that target psychological factors may be designed to investigate which aspects of therapy in general, or of particular types of therapy—such as the grief box therapy—are most helpful. In this section we consider factors that influence research on treatments.

| Therapy variables | Patient variables | Therapist variables | Patient–therapist interaction variables |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Common Factors and Specific Factors

Just as placebos can provide relief even though they lack medically beneficial ingredients, the very act of seeing a therapist or counselor—or even setting up a meeting with one—may provide relief for some disorders (regardless of the specific techniques or theoretical approach of the therapist or counselor). Such relief may result from, at least in part, common factors, which are helpful aspects of therapy that are shared by virtually all types of psychotherapy. According to results from numerous studies (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Wampold, 2010), common factors can include:

- opportunities to express problems;

- some explanation and understanding of the problems;

- an opportunity to obtain support, feedback, and advice;

- encouragement to take (appropriate) risks and achieve a sense of mastery;

- hope; and

- a positive relationship with the therapist.

Common factors Helpful aspects of therapy that are shared by virtually all types of psychotherapy.

Common factors, and certain patient characteristics—such as being motivated to change (Bohart & Tallman, 2010; Clarkin & Levy, 2004)—can contribute more to having a positive outcome from therapy than the specific techniques used. If the grief box therapy were effective, it might be because of such common factors and not something unique to your particular method.

Specific factors The characteristics of a particular treatment or technique that lead it to have unique benefits, above and beyond those conferred by common factors.

The existence of common factors creates a challenge for researchers who are interested in determining the benefits of a particular type of treatment or technique. The characteristics that give rise to these unique benefits of a specific type of treatment are known as specific factors. For instance, when researching grief box therapy, you might want to investigate whether the process of creating the grief box provides benefits above and beyond the common factors that any therapy provides.

In fact, research has shown that common factors alone may not be sufficient to produce benefits in therapy for some disorders (Elliott et al., 2004; Kirschenbaum & Jourdan, 2005; Lambert, 2004); at least for some disorders, specific factors play a key role in treatment. The leftmost column in TABLE 4.3 notes specific factors—the therapy variables—that are the subject of research targeting psychological treatments. (In subsequent chapters, we will discuss research on treatments for specific disorders; such studies typically examine specific factors.)

Is Therapy Better Than No Treatment?

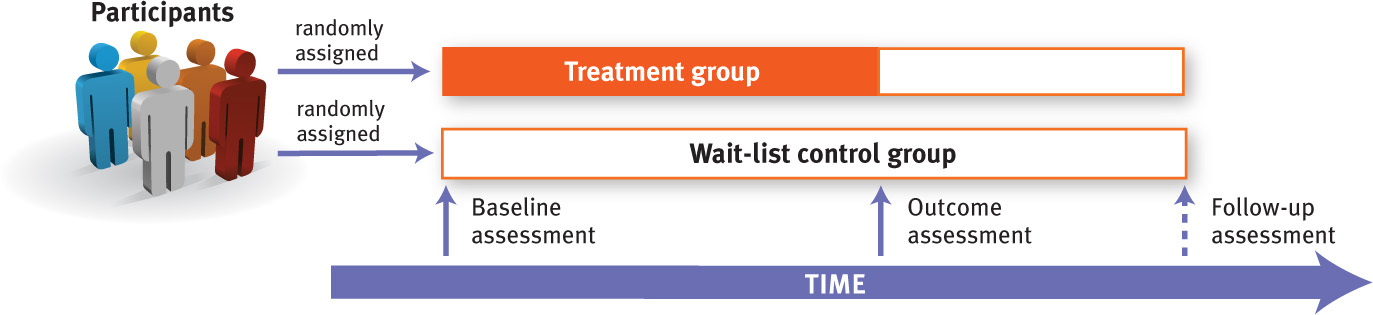

Researchers have questioned whether people actually improve more by receiving therapy than they would have improved if they hadn’t received any treatment. To address this question, researchers randomly assign participants to one of two groups: “treatment” and “no treatment.” However, participants in the “no treatment” group are often assigned to a waiting list for treatment (which is ethically preferable to not providing any treatment at all), and thus this group is often called a wait-list control group (Kendall et al., 2004, Lambert & Bergin, 1994). Researchers usually assess the dependent variable, such as level of symptoms, in both groups at the beginning of the study, before treatment begins—this is their baseline assessment. Then, researchers assess the same variables again after the treatment period (for the wait-list control group, this means assessing symptom level after the same duration of time as that over which the treatment group received treatment); this is called the outcome assessment. Researchers then compare the results of the two groups, and may also assess the variables at a later follow-up point, called a follow-up assessment (see Figure 4.4).

Alternatively, instead of (or in addition to) a “no treatment” or wait-list control group, researchers may use a placebo control group, the members of which meet with a “therapist” with the same frequency as the members of the treatment group. The “placebo therapist” refrains from using any of the active treatment techniques employed in the treatment group, but patients still receive attention and some level of support. For a study of your grief box therapy, a placebo control group might consist of patients who meet with therapists who listen to their concerns or complaints—without grief boxes, social support, or any other specific interventions.

With either type of control group—wait-list or placebo—the symptoms of members of the control group might diminish simply with the passage of time. Thus, the crucial comparison is not whether people in the treatment group got better but rather how much more they improved than did the people in the control group.

Researchers have conducted such studies for over half a century. How did they answer the question of whether therapy works? With a resounding “yes.” Therapy really does make a difference (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Wampold, 2010). And, not surprisingly, treatment shows a larger effect when a treatment group is compared to a wait-list control group than when a treatment group is compared to a placebo group, which highlights the beneficial effects of common factors (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Roth & Fonagy, 2005; Wampold, 2010).

But what does it really mean to say that therapy works? The results must have clinical significance, which means that they change a person’s life in meaningful, practical ways. Assessments of clinical significance may be based on the patients’ own perceptions, on observations of friends and family members of the patients, or on the therapists’ judgment.

Is One Type of Therapy Generally More Effective Than Another?

With the advent of behavior therapy in the 1960s, some researchers asked whether one type of therapy is generally more effective than another. The initial results of such research were surprising: No type of therapy appeared to be more effective than another. This first generation of research on specific treatments found that, in general, any type of the treatments of psychological disorders led to better outcomes than no treatment, and no single treatment was superior to others. The latter finding became referred to as the Dodo bird verdict of psychotherapy (Luborsky et al., 1975), after the character in the book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland who states: “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes.”

However, by the 1980s, a second generation of such research had begun, and researchers refined the methods and procedures they used to provide therapy and assess its outcome. Let’s briefly consider key advances in how researchers study the effects of various psychotherapies.

Randomized Clinical Trials

Randomized clinical trial (RCT) A research design that has at least two groups—a treatment group and a control group (usually a placebo control)—to which participants are randomly assigned.

Different types of therapy are in fact better suited than others for treating different disorders. This became clear during the second generation of research, which began with the Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program study (TDCRP; Elkin et al., 1985). This study used a research design analogous to the design used to measure the effect of a medication on symptoms of a medical disorder; this research design is referred to as a randomized clinical trial (RCT; also referred to as randomized controlled trial). RCTs have at least two groups—a treatment group and a control group (usually a placebo control)—and participants are randomly assigned to the groups (Kendall et al., 2004). RCTs may also involve patients and therapists at multiple sites in a number of cities.

RCTs are the best way to evaluate therapies because they use the scientific method to identify the specific factors that underlie a beneficial treatment. The independent variable is often the type of treatment or technique, as it was in the TDCRP, but it can be any other variable listed in TABLE 4.3. The dependent variable is usually some aspect of patients’ symptoms—such as frequency or intensity—or quality of life.

RCTs generally require therapists to base their treatments on detailed manuals that provide session-by-session guidance and specify techniques to be used with patients. RCTs provide brief therapy, typically from 6 to 16 sessions. Manual-based treatment ensures that all therapists who use one particular approach provide similar therapy that is distinct from other types of therapy (Kendall et al., 2004; Nathan, Skinstad, & Dolan, 2000).

The TDCRP was designed to compare the benefits of four kinds of treatment for depression given over 16 weeks: interpersonal therapy (IPT, interpersonal therapy, a time-limited therapy that focuses on relationships; we will discuss this treatment in more detail in Chapter 5), cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), the antidepressant medication imipramine (which was widely used at the time of the study) together with supportive sessions with a psychiatrist, and a placebo medication together with supportive sessions with a psychiatrist. Various dependent variables were measured. The main results told an interesting story: At the 18-month follow-up assessment, the CBT group had a larger sustained effect and fewer relapses, especially compared with the imipramine group (Elkin, 1994; Shea et al., 1992). But when the most severely depressed patients in each group were compared, IPT and imipramine were found to have been more effective than CBT (Elkin et al., 1995). However, most important in this study, the quality of the “collaborative bond” between therapist and patient (which was assessed by independent raters who viewed videotapes of sessions) had an even stronger influence on treatment outcome than did the type of treatment (Krupnick et al., 1996).

The Importance of Follow-up Assessment

It’s one thing for a type of therapy to have an immediate effect, but another—and usually more important—thing for it to produce enduring change. The TDCRP study followed patients for over 18 months after treatment ended, but some studies—because of financial or logistical constraints—do not make any follow-up assessment. This is unfortunate because one type of treatment may be more beneficial at the end of therapy, but those patients may have a higher rate of relapse a year later, leaving the patients in another treatment group better off in the long run (Kendall et al., 2004).

Allegiance Effect

Allegiance effect A pattern in which studies conducted by investigators who prefer a particular theoretical orientation tend to obtain data that supports that particular orientation.

Another issue in RCT research is the allegiance effect, in which studies conducted by investigators who prefer a particular theoretical orientation tend to obtain data that support that particular orientation (Luborsky et al., 1999). Specifically, RCT investigators who support one type of treatment tend to have patients who do better with that type of treatment, whereas patients in the same study (using the same manuals) whose investigators support a different type of treatment tend to do better with that treatment. This means that even the use of manuals is not enough to control all types of confounds completely.

Different Therapies for Different Disorders

The bottom line is that a specific type or types of therapy are in general best suited for treating specific types of disorders. We will discuss which types of therapy are best for which specific disorders in later chapters of this book. In fact, enough is now known about the effectiveness of particular types of therapy for particular disorders that clinicians should have an evidence-based practice; that is, for each patient, they should pick a treatment or set of techniques that research has shown to be effective for that patient’s problem. (Such a judgment should also take into account sociocultural factors, as well as the therapist’s preference for—and training in—a particular method.)

The Therapy Dose–Response Relationship

Dose–response relationship The association between more treatment (a higher dose) and greater improvement (a better response).

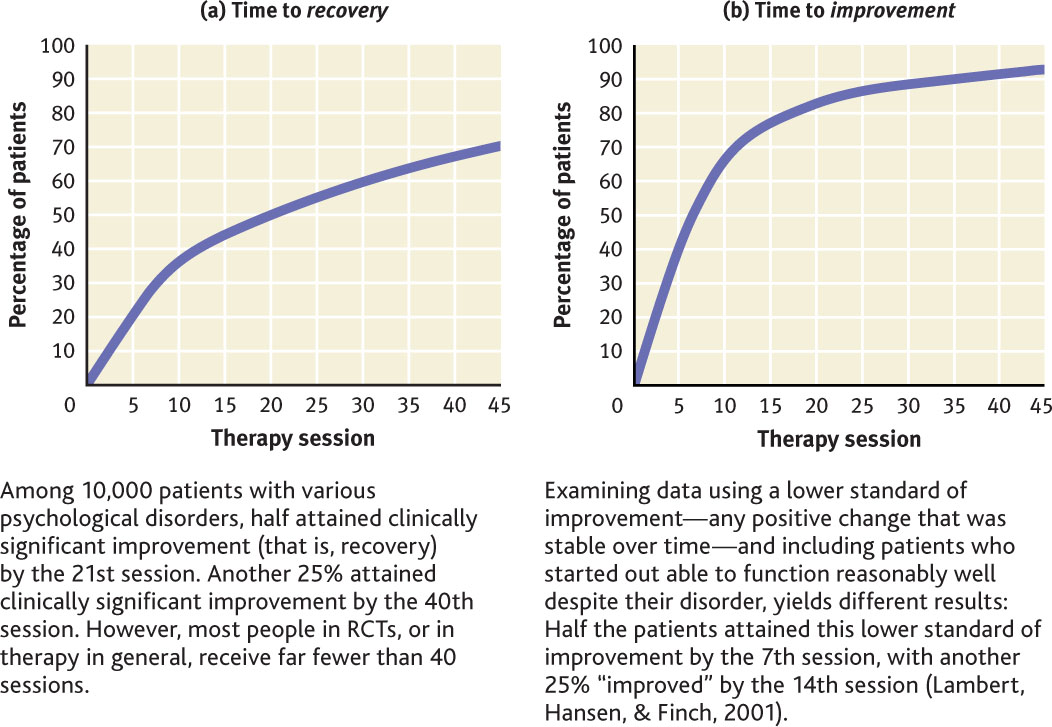

Is more treatment related to greater improvement? In other words, is a higher “dose” of therapy (more sessions) associated with a better “response”? This association between dose and response is referred to as the dose–response relationship, and research suggests that the general answer to this question is yes. More sessions are associated with a better outcome (Hansen, Lambert, & Forman, 2002; Shadish et al., 2000). In general, patients improve the most during the early phase of treatment (see Figure 4.5), and they continue to improve, but at diminishing rates, over time (Lutz et al., 2002). There are individual exceptions to this general pattern; people with more severe or entrenched problems, such as schizophrenia or personality disorders, may not show as much benefit in the early stages of therapy but rather may only improve over a longer period of time.

The dose–response relationship is correlational; it does not indicate whether the increased number of sessions causes the increased response. It is possible that people who are feeling better during the course of treatment are more eager or more willing to attend additional sessions than those who are not responding as well. If this were the case, the response would be “causing” the increased dose (increased number of sessions) (Otto, 2002; Tang & DeRubeis, 1999). Alternatively, both dose and response could be affected by some other factor. As noted earlier in this chapter, correlation does not imply causation.

Researching Treatments That Target Social Factors

Robert Glusic/Getty Images

Research on treatment also may investigate the possible benefits of targeting social factors or the ways in which treatment may be affected by the larger social context.

Gender and Ethnicity of Patient and Therapist

All types of psychotherapy involve a relationship between two (or more) people. Therapists and patients may be similar with regard to racial or ethnic background and gender, or they may be different. Does such a difference matter? Research suggests not: Differences between patient and therapist in ethnicity, gender, and age do not systematically alter how effective therapy is (Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 1999; Lam & Sue, 2001; Maramba & Hall, 2002). However, with regard to gender, one study found that women and men are both less likely to drop out of treatment if they have a female therapist (Flaherty & Adams, 1998).

Nevertheless, some people prefer a therapist with a similar ethnic or racial background to their own. For those with a strong preference, such as some Asian Americans, matching the ethnicity of the patient and therapist may lead to better outcomes (Sue et al., 1994), and it can result in lower dropout rates among non-Whites (Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 1999; Sue et al., 1999).

Research on matching by ethnicity usually involves broad categories, such as patient and therapist who are both Asian American. However, when patients prefer a therapist from their own ethnic group, matching them with a therapist from a broadly similar group may not suffice. A Korean American patient, for instance, may prefer a Korean American therapist, but if such a therapist is not available, that patient may not prefer a Chinese American therapist over a therapist of any other background (Karlsson, 2005).

Culturally Sanctioned Placebo Effects

We’ve seen that placebos can be very powerful. It turns out that different products and practices may operate as placebos in different cultures. Throughout time and across cultures, people in the role of healer have used different methods to treat abnormality—and at least some of these methods may have relied on the placebo effect. For instance, among the Shona people of Africa, those who have psychological problems often visit a n’anga (healer), who may recommend herbal remedies or steam baths, or may throw bones to determine the source of a person’s “bewitchment.” Once the source is determined, the ill person’s family is told how to mend community tensions that may have been caused by a family member’s transgressing in some way (Linde, 2002). These n’anga’s treatments, if effective, may work because of the placebo effect and the common factors that arise from any treatment (even a placebo): hope, support, and a framework for understanding the problem and its resolution.

But members of nonindustrialized societies are not the only ones who are susceptible to such cultural forces. In Western cultures over the past two decades, people diagnosed with depression who are enrolled in studies to evaluate various medications have responded progressively more strongly to placebos (Walsh, Seidman, et al., 2002). Over that same two decades, pharmaceutical companies have increasingly advertised their medications directly to potential consumers, informing them about the possible benefits of the drugs. It is possible that the participants in these studies became more likely to believe that medication will be helpful than were participants 30 years ago, before direct advertising to consumers. And, in fact, research suggests that expectations that symptoms will improve may account for the lion’s share of the positive response to an antidepressant among people with depression (Kirsch, 2010; Kirsch & Lynn, 1999; Walach & Maidhof, 1999).

Ethical Research on Experimental Treatments

Any research on treatment conducted by a psychologist is bound by the ethical guidelines for research and usually must be approved by an IRB, discussed earlier in the chapter. As shown in TABLE 4.4, research on a new type of treatment—an experimental treatment such as your grief box therapy—is subject to additional guidelines because the researchers may not be aware of some of the risks and benefits of the new treatment at the outset of the study.

Psychologists conducting research on experimental treatments must clarify to participants at the outset of the research:

|

| Source: Copyright © American Psychological Association. For more information, see the Permissions section. |

Thinking Like A Clinician

Based on a survey, County Community College has found that 23% of its first-year students have anxiety or depression severe enough to meet the DSM-5 criteria. The college would like to institute a treatment program for these students. In fact, the staff at the counseling center plans to conduct a research study and offer several different types of treatment: medication (if appropriate), CBT with an individual therapist, and CBT in group therapy. Students can sign up for whichever type of treatment they prefer and can even receive more than one type of treatment. The results will be recorded and used to guide how treatment is provided in the future. Is this study a randomized clinical trial? Why or why not? What are some potential problems with the research design of this study? To learn whether each of the treatments is helpful to students, what questions should be asked of the students before and after the study?