13.3 Dramatic/Erratic Personality Disorders

In her memoir, Rachel Reiland recalls an occasion when a minor matter set off an escalating fight between her and her husband. She raged at him until she realized that she might drive him away. So she decided to leave him before he had a chance to leave her. She ran out of the house barefoot and then ran for miles through the city. After several hours, her husband and children—who had been searching for her—pulled up their car beside her and brought her home (Reiland, 2004).

Reiland’s response to this fight with her husband exemplifies the typical reactions of people with Cluster B personality disorders: impulsive, dramatic, and erratic behaviors. These disorders arise because of difficulty regulating emotions. This commonality can sometimes make it difficult to determine which specific Cluster B personality disorder a given patient has; many of the symptoms specified in the diagnostic criteria are not unique to a single personality disorder in the cluster (Blais et al., 1999; Zanarini & Gunderson, 1997). People with a dramatic/erratic personality disorder also tend to have certain additional psychological disorders: substance-related disorders, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, or eating disorders (Dolan-Sewell et al., 2001; McGlashan et al., 2000; Skodol et al., 1999; Zanarini et al., 1998).

Antisocial Personality Disorder

One day, Reiland was particularly angry, and she put the following note on the front door: “You need to pick up the kids. I’m upstairs in the attic. Don’t even think of going up there if you know what’s good for you!” Another note was on the attic door, which was locked: “I might die anyway, but if you dare come in here, you might all be dead! You don’t know what I have up here!” (Reiland, 2004.

Antisocial personality disorder A personality disorder diagnosed in adulthood characterized by a persistent disregard for the rights of others.

Some might say that Reiland’s behavior—and her apparent lack of concern for how her husband and children might respond to the notes—had elements of antisocial personality disorder, which involves a persistent disregard for the rights of others. As noted in TABLE 13.9, people with antisocial personality disorder may violate rules or laws (for example, by stealing) and may lie or act aggressively, hurting others, believing that they are entitled to break the rules (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). They may also act impulsively, putting themselves or others at risk of harm. In addition to these behaviors, people with antisocial personality disorder shirk their responsibilities—they don’t pay their bills or show up for work on time, for instance. They may also exhibit a fundamental lack of regret for or guilt about their antisocial behaviors, seeming to lack a conscience, a moral sense, or a sense of empathy. In Reiland’s case, though, holing up in the attic and writing the threatening notes probably resulted from uncontrollable emotions rather than from a disregard for others.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

The diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality disorder are the most behaviorally specific of the criteria for personality disorders and even include overt criminal behaviors (Skodol, 2005). Because of this specificity, antisocial personality disorder is the most reliably diagnosed personality disorder (Skodol, 2005).

Conduct disorder A psychological disorder that typically arises in childhood and is characterized by the violation of the basic rights of others or of societal norms that are appropriate to the person’s age.

Like other personality disorders, antisocial personality disorder manifests itself in childhood or adolescence, but DSM-5 is again very specific about antisocial personality disorder: The symptoms must have arisen by age 15, although the diagnosis cannot be made until the person is at least 18 years old; this was true of John in Case 13.5. The diagnosis for people who exhibit a similar pattern of symptoms but are younger than 18 is conduct disorder, which is characterized by consistently violating the rights of others (through lying, threatening, and destructive and aggressive behaviors) or violating societal norms and typically diagnosed in children and adolescents. (In Chapter 14 we discuss conduct disorder in detail.) TABLE 13.10 provides additional facts about antisocial personality disorder.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, citations are to American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

CASE 13.5 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Antisocial Personality Disorder

John and his sister were adopted by the same family when they were respectively 1.5 and 3 years of age. From the very beginning, John was severely physically abused by his adoptive father as a result of just minor misbehaviors. Furthermore, John felt that he and his sister were neglected (lack of warmth and attention) by his adoptive parents and that he and his sister were thought of much less highly by them than their only biological son. From age 10 John and his sister were sexually abused on a regular basis by his adoptive father, and John was forced to watch when his father raped his sister. He demonstrated more and more oppositional and angry behavior, and he became a notorious thief. John left junior secondary technical school prematurely and had many short-term jobs, but he was dismissed every time because of lack of motivation, disobedience, and/or theft. As a consequence of his deviant behavior, John was placed in a juvenile correctional and observation institute when he was 16 years of age. A psychiatric report from this episode described him as a socially, emotionally, morally, and sexually underdeveloped person who was very suspicious and angry. He projected his discomfort on the outside world. After his release from the juvenile correctional institute (when he was 18 years of age), John was arrested because of violent pedophilic rape, theft, and fraud. John was sentenced to forensic psychiatric treatment. But soon after his release, when he was 24, John was sentenced to life imprisonment because he committed an excessively violent sexual homicide on a 9-year-old boy.

(Martens, 2005, pp. 117–118)

Psychopathy A set of emotional and interpersonal characteristics marked by a lack of empathy, an unmerited feeling of high self-worth, and a refusal to accept responsibility for one’s actions.

The term psychopath (or sociopath, which was used in the first DSM) has often been used to refer to someone with symptoms of antisocial personality disorder. However, psychopathy emphasizes specific emotional and interpersonal characteristics, such as a lack of empathy, an unmerited feeling of high self-worth, and a refusal to accept responsibility for one’s actions—as well as antisocial behaviors. The classification of psychopathy is narrower (i.e., more restrictive, because there are more criteria) than the diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. In contrast, the diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder tends to focus more on behaviors—mostly criminal ones, such as stealing or breaking other laws—than on the personality traits that may underlie the behaviors. Only a minority of prisoners (15% of male prisoners, 7.5% of female prisoners) meet the specific criteria for psychopathy, but a majority of prisoners (50–80%) meet the broad behavioral criteria for antisocial personality disorder (Hare, 2003).

Psychopathy is generally considered to be a more universal concept than antisocial personality disorder; most cultures recognize a similar cluster of psychopathic characteristics (Cooke, 1998; Gacono et al., 2001).

Understanding Antisocial Personality Disorder and Psychopathy

The concept of psychopathy has been employed longer than the diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. Hence, more research has addressed psychopathy and criminality than antisocial personality disorder—and the relative lack of research on antisocial personality disorder makes it difficult to identify the factors that contribute to the disorder (Ogloff, 2006). Moreover, most research that does examine factors that contribute to antisocial personality disorder has studied participants who are or have been in prisons or jails or who have comorbid substance abuse problems; hence, numerous confounds prevent us from conclusively identifying the factors that contribute solely to antisocial personality disorder. Therefore, the following sections examine neurological, psychological, and social factors—and the feedback loops among them—that contribute to antisocial personality disorder and/or psychopathy, keeping in mind the limitations of existing research.

Neurological Factors in Antisocial Personality Disorder and Psychopathy

People with antisocial personality disorder or psychopathy (and the groups have not been rigorously separated in most of this research) may have abnormal brain structures as well as abnormal brain function (Pridmore et al., 2005).

First, regarding brain structure, people with antisocial personality disorder or psychopathy tend to have unusually small frontal lobes (Raine et al, 2000). The smaller frontal lobes might suggest problems in inhibiting and planning behavior.

Second, regarding brain function, the frontal and temporal lobes of these patients tend to show less activation than normal during many tasks (Schneider et al., 2000; Smith, 2000; Völlum et al., 2004). Moreover, these patients exhibit deficits on tasks that rely on the frontal lobes, such as those requiring planning or discovering that a rule has been changed (Dolan & Park, 2002). Such deficits probably contribute to their problems in inhibiting and planning behavior.

Antisocial personality disorder has been linked to genes that regulate dopamine production (Prichard et al., 2007) and also to genes that regulate serotonin (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2007). Genes that affect dopamine and serotonin may influence temperament and have been linked to being highly motivated by the possibility of reward (Gray, 1987), not being strongly motivated by the threat of punishment (Cloninger et al., 1993; Gray, 1987; Lykken, 1995), and having low frustration tolerance—which often leads to impulsive behavior and a tendency to take shortcuts.

However, effects of genes are modulated by the environment. Adoption studies have found that the environment in which a child is raised influences the risk of criminal behavior or antisocial personality disorder only if the child is biologically vulnerable, as shown in TABLE 13.11. When a child’s biological parents were not criminals, the child’s later criminal behavior was unaffected by environmental influences, such as the number of foster placements before adoption or the adoptive parents’ criminality (Caspi et al., 2002; Mednick et al., 1984).

| Biological parents’ criminality | ||

|---|---|---|

| Exposure to environmental forces associated with criminality | High | Low |

| High | 40.0% | 6.7% |

| Low | 12.1% | 2.9% |

| Note: Environmental forces associated with criminality include variables such as the number of foster placements before adoption and the adoptive father’s socioeconomic status. | ||

| Source: Brock et al., 1996. For more information see the Permissions section. | ||

Psychological Factors in Antisocial Personality Disorder and Psychopathy

Antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy appear to develop, in part, because of problems with classical and operant conditioning processes. Whereas classical conditioning and operant conditioning lead most people to learn to avoid encounters with a painful stimulus (such as a shock), criminals with psychopathic traits do not learn to avoid painful stimuli. Thus, they cannot easily learn from punishing experiences (Eysenck, 1957) and are likely to repeat behavior associated with negative consequence, despite receiving punishment, such as a prison sentence (Zuckerman, 1999). And because they are highly motivated by rewarding activities, they are less inclined to inhibit themselves to avoid punishment; they thus behave in ways that are impulsive, have difficulty delaying gratification, and have poor judgment (Silverstein, 2007).

Social Factors in Antisocial Personality Disorder and Psychopathy

One risk factor for conduct disorder and subsequent antisocial personality disorder is a child’s relationship with his or her parents or primary caretakers. Each parent or other primary caretaker has a style of interacting with the child from infancy. Some parents abuse or neglect their children or are inconsistent in disciplining them, which can lead to an insecure attachment (Bowlby, 1969). These children have a relatively high risk of developing conduct disorder and later antisocial personality disorder (Levy & Orlans, 1999, 2000; Ogloff, 2006; Shi et al., 2012). Note, however, that this finding is simply a correlation and does not necessarily mean that attachment difficulties cause later antisocial behavior; it is possible that some other variable both interferes with a child’s developing normal attachment and promotes antisocial behaviors.

Other childhood factors associated with the later development of antisocial personality disorder include poverty, family instability, and—in those who are genetically vulnerable—adoptive parents’ criminality (Raine et al., 1996).

Feedback Loops in Understanding Antisocial Personality Disorder and Psychopathy

ONLINE

Various factors create feedback loops that ultimately produce psychopathy or antisocial personality disorder. Twin and adoption studies reveal that some people have a predisposition toward criminality or associated temperaments (neurological factor), but the environment in which children grow up (social factor) influences whether that predisposition is likely to lead to criminal behavior. One study found that children with conduct disorder who were punished for their offenses were less likely to develop antisocial personality disorder later in life, confirming the contribution of operant conditioning to the disorder (Black, 2001).

However, the types of temperaments that are associated with antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy can impede the types of classical and operant conditioning processes that promote empathy and discourage antisocial behaviors (psychological factor; Kagan & Reid, 1986; Martens, 2005; Pollock et al., 1990). Moreover, the experience of abuse or neglect by parents (social factor) may contribute to a tendency toward underarousal (Schore, 2003), which in turn leads people to seek out more arousing (and reckless) activities that may increase their risk of seeing or experiencing violence (Jang et al., 2001)—which they may find stimulating, and which then may reinforce such behavior.

Treating Antisocial Personality Disorder and Psychopathy

Most research on treatment involves people who are diagnosed with psychopathy, not antisocial personality disorder specifically. Some of the personality traits associated with psychopathy interfere with a therapeutic collaboration: problems in delaying gratification, lack of empathy, and low frustration tolerance. Psychopathy has a poor prognosis, and treatments developed thus far are not likely to alter behavior or reduce symptoms (Gacono et al., 2001; Rice et al., 1992; Serin, 1991). People with psychopathy who are in prison are likely to commit additional crimes after their release (Ogloff et al., 1990; Seto & Barbaree, 1999). When a person with psychopathy is violent, managing the patient may be more realistic and appropriate than treating the patient’s personality problems (Ogloff, 2006).

Ultimately, a challenge in treating people with antisocial personality disorder is their lack of motivation. Because they aren’t disturbed by their behavior, they are rarely genuinely motivated to change, which makes any real collaboration between therapist and patient unlikely; patients often will attend therapy only when required to do so. Treatment generally focuses on changing overt behaviors (Farmer & Nelson-Gray, 2005).

Treatments for people with antisocial personality disorder who are not psychopathic have some success—at least in the short term. These treatments focus on comorbid substance abuse and aggressive behavior (Henning & Frueh, 1996). The most effective treatments provide clear rules about behavior—including clear and consistent consequences for rule violations—and target behavior change and behavioral control, as is addressed with CBT.

CURRENT CONTROVERSY

Should Psychopaths Receive Treatment?

Psychopathy has a distinctive pattern of interpersonal, behavioral, and affective symptoms (Hare, 1997). According to Hare (1993, p. 25), “psychopaths can be described as intraspecies predators who use charm, manipulation, intimidation and violence to control others and to satisfy their own selfish needs.” Psychopathy is a difficult disorder to treat, and individuals with psychopathy rarely seek treatment unless it is for self-serving purposes such as probation or parole (Hare, 1993). The question arises, then, as to whether psychopaths should receive treatment at all.

Studies on the efficacy of treatment in psychopathy have been mixed (Salekin et al., 2010), with some research reporting higher recidivism rates in psychopaths who received treatment (Rice et al., 1992). Others have suggested that psychopaths who complete treatment may merely be perfecting their interpersonal skills to manipulate others (Hare, 1997; Hart, 1998). For example, Rice et al. (1992) measured the effects of an intensive treatment program on violent psychopathic and nonpsychopathic forensic patients. After a 10-year follow-up, the violent recidivism rate was 55% for untreated psychopaths, and 77% for treated psychopaths. Researchers have also noted that no effective treatments are available to treat psychopathy (O’Neill et al., 2003), regardless of the type of setting (e.g., community), and psychopaths tend to drop out of treatment programs early (Ogloff et al., 1990).

On the other hand, in a review of three studies designed to reduce violence and offending behaviors in psychopathic offenders, Wong et al. (2012) reported positive treatment outcomes. Olver and Wong (2009) found that psychopathic sex offenders who completed treatment were less likely to violently reoffend. Other researchers (D’Silva et al., 2004; Salekin, 2002), however, have pointed out several methodological flaws in many of the studies measuring treatment response in psychopathy.

CRITICAL THINKING If you were to treat a psychopath, what outcome measures could you assess to ensure that therapy was indeed effective? In your opinion, how should forensic psychologists treat psychopaths: as criminals or individuals with a mental illness? Why?

(Richard Conti, Kean University)

Borderline Personality Disorder

Borderline personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by volatile emotions, an unstable self-image, and impulsive behavior in relationships.

The term borderline personality originally was used by psychodynamic therapists to describe patients whose personality was on the border between neurosis and psychosis (Kernberg, 1967). Now, however, it is generally used to describe the DSM-5 personality disorder that includes some features of that type of personality: borderline personality disorder is characterized by volatile emotions, an unstable self-image, and impulsive behavior in relationships (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder are noted in TABLE 13.12. A key criterion is emotional dysregulation (also known as affective instability), which leads the person frequently to respond more emotionally than a situation warrants and to display quickly changing emotions—lability (Glenn & Klonsky, 2009). Another prominent criterion refers to a relationship pattern of idealizing the other person at the beginning of the relationship, spending a lot of time with the person and revealing much, thus creating an intense intimacy. But then positive feelings quickly switch to negative ones, which leads the person with this disorder to devalue the other person. Rachel Reiland’s pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors meet the criteria for borderline personality disorder. Reiland describes the switch in how she viewed other people:

A pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects, and marked impulsivity, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

I saw people as either good or evil. When they were “good,” I vaulted them to the top of a pedestal. They could do no wrong, and I loved them with all of my being. When they were “bad,” they became objects of scorn and revenge.

In relationships with those closest to me, the “good” and “bad” assessments could alternate wildly, sometimes from one hour to the next. The unrealistic expectations of perfection that came with the good-guy pedestal were destined to be unfulfilled, which led to disappointment and sense of betrayal.

(2004, p. 88)

The highly fluid and impulsive behaviors that are part of borderline personality disorder occur in part, because of the patient’s strong responses to emotional stimuli, which may stem from difficulty understanding emotions (Peter et al., 2013). For example, if a patient with borderline personality disorder has to wait for someone who is late for an appointment, the patient often cannot understand and regulate the ensuing powerful feelings of anger, anxiety, or despair, which can last for days. The person with this personality disorder is extremely sensitive to any hint of being abandoned, which also can cause strong emotions that are then difficult to bring under control.

When not in the throes of intense emotions, people with borderline personality disorder may feel chronically empty, lonely, and isolated (Klonsky, 2008). When feeling empty, they may harm themselves in some nonlethal way—such as superficial cutting of skin—in order to feel “something”; such behavior has been called parasuicidal rather than suicidal because the intention is not to commit suicide but rather to gain relief from feeling emotionally numb. The parasuicidal behavior usually occurs when the person is in a dissociated state, often after he or she has felt rejected or abandoned (Livesley, 2001). More worrying to clinicians, family members, and friends is when self-harming behavior is a suicide attempt. People with borderline personality disorder may have comorbid depression, which frequently contributes to increased suicidal thoughts, plans, or attempts. When borderline personality disorder symptoms diminish—including a decrease in emotional sensitivity—depression is likely to improve (Gunderson et al., 2004). TABLE 13.13 provides additional facts about borderline personality disorder. Donna, in Case 13.6, exhibits extreme emotional sensitivity.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, citations should be for American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

CASE 13.6 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Borderline Personality Disorder

[A woman, Donna, exhibited] episodes of explosive anger and bitter tirades, along with weekly (sometimes daily) expressions of bitterness and resentment. Frustrations and disappointments, which are inevitable within any relationship and would only be annoying inconveniences to most people, were perceived by Donna as outrageous mistreatments or exploitations. Even when she recognized that they did not warrant a strong reaction, she still had tremendous difficulty stifling her feelings of anger and resentment. Her tendency to misperceive innocent remarks as being intentionally inconsiderate (at times even malevolent) further exacerbated her propensity to anger. She acknowledged that she would often push, question, and test her friends and lovers so hard for signs of disaffection, reassurances of affection, or admissions of guilt, that they would become frustrated and exasperated and might eventually lash out against her. She would often find herself embroiled in fruitless arguments that she subsequently regretted. She had no long-standing relationships, but there were numerous people who remained embittered toward her. Three marriages had, in fact, all ended in acrimonious divorce.

(Widiger et al., 2002, p. 443)

Understanding Borderline Personality Disorder

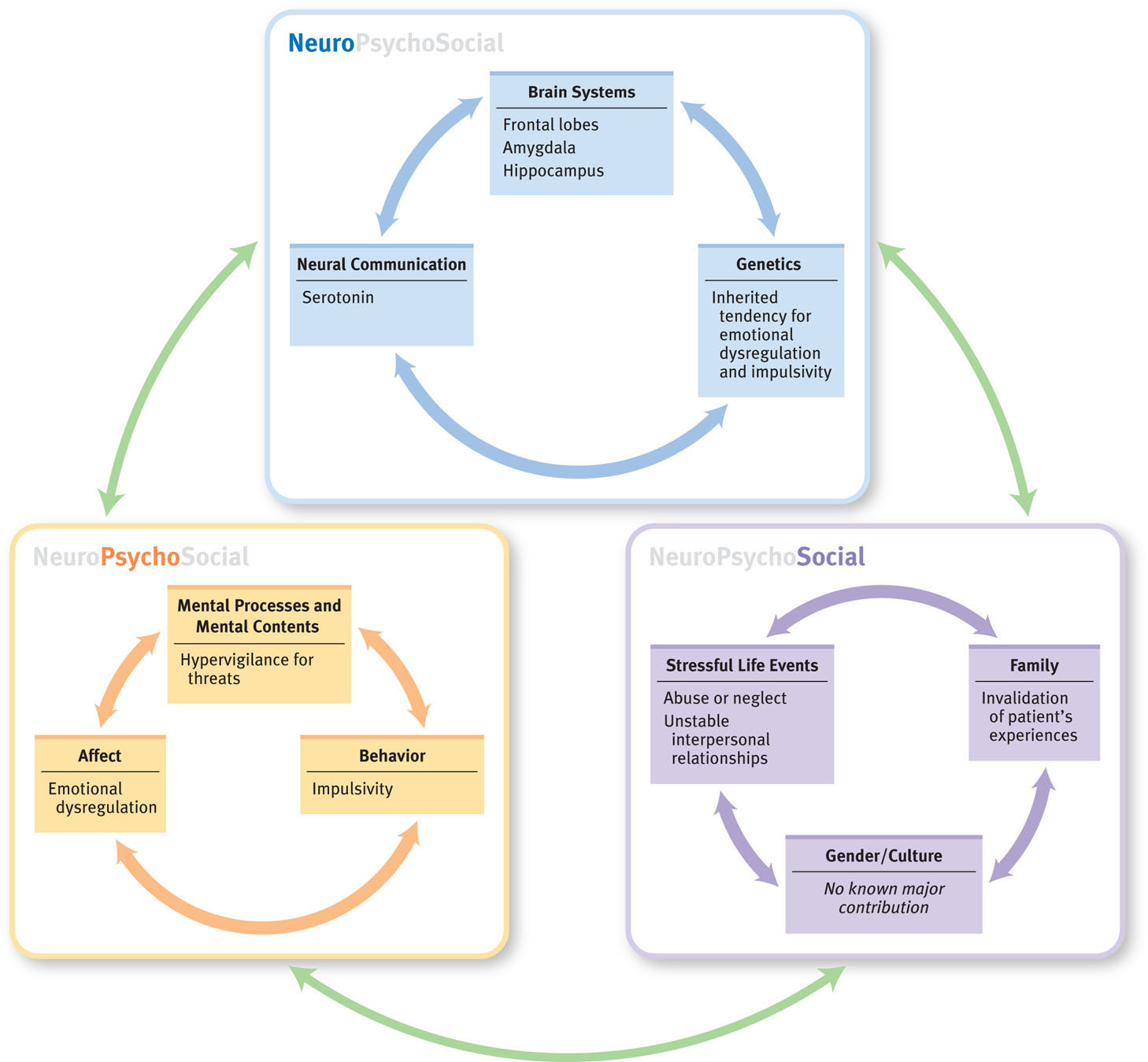

The neuropsychosocial approach allows us to appreciate the complexity of borderline personality disorder. In fact, this approach underlies the most comprehensive analysis that has been made of the disorder and its treatment (Linehan, 1993).

Neurological Factors: Born to Be Wild?

Considerable research has been reported on the neurological bases of borderline personality disorder.

Brain Systems The frontal lobes, hippocampus, and amygdala are unusually small in people with borderline personality disorder (Driessen et al., 2000;Schmahl, Vermetten et al., 2003; Tebartz van Elst et al., 2003). These structures are part of a network of brain areas that functions abnormally in people with this disorder. The frontal lobes (which are involved in regulating emotions and formulating plans) are less strongly activated in these patients than is normal. Consistent with findings from neuroimaging studies, numerous studies have shown that people who have borderline personality disorder have difficulty performing tasks that rely on the frontal lobes (LeGris & van Reekum, 2006); specifically, people with this disorder also have difficulty focusing attention, organizing visual material, and making decisions (LeGris & van Reekum, 2006).

The amygdala (which is involved in the perception and production of strong emotions, notably fear) is more strongly activated than normal in these patients when they see faces with negative expressions (Donegan et al., 2003). This finding makes sense because the frontal lobes normally inhibit the amygdala (LeDoux, 1996); thus, if the frontal lobes are not working properly, they may fail to keep activation of the amygdala within a normal range.

In addition, consistent with the unusually small hippocampus, these patients have impaired visual and verbal memory (LeGris & van Reekum, 2006).

Neural Communication Relatively low levels of serotonin are related to impulsivity, which is characteristic of borderline personality disorder. Thus, it is not surprising that these patients have been shown to have abnormal serotonin functioning (Soloff et al., 2000); in particular, their serotonin receptors are less sensitive than normal, and thus the effects of serotonin are diminished (Hansenne et al., 2002). In addition, this dysfunction involving serotonin is apparently greater in women than in men with the disorder (New et al., 2003; Soloff, Kelly et al., 2003)—and many more women than men receive this diagnosis.

Thus, people with borderline personality disorder are likely to be neurologically vulnerable to emotional dysregulation. This vulnerability is usually expressed as a low threshold for emotional responding, with responses that are often extreme and intense. In addition, the brains of these people are relatively slow to return to a normal baseline of arousal.

Genetics Genetic studies reveal a genetic vulnerability to components of this disorder, such as impulsivity, emotional volatility, and anxiety (Adams et al., 2001; Heim & Westen, 2005; Skodol, Siever, et al., 2002).

Psychological Factors: Emotions on a Yo-Yo

The core feature of borderline personality disorder is dysregulation—of emotion, of sense of self, of cognition, and of behavior (Robins et al., 2001). The behaviors of people with this disorder can be extreme: In one instant, they will fly into a rage over some inconsequential thing, but in the next instant, they will break down in tears and beg for reassurance, as Reiland did. These behaviors may inadvertently be reinforced by family members’ attention.

People with this disorder often engage in other behaviors that are more directly self-destructive—including substance use or abuse, binge eating, and parasuicidal behaviors; they may act in these ways to try to feel better after interpersonal stress (Paris, 1999). And, in fact, such maladaptive behaviors can be (negatively) reinforcing because they do temporarily relieve emotional pain. (Recall that negative reinforcement is different from punishment; removing something aversive is reinforcing.)

Social Factors: Invalidation

Borderline personality disorder also involves interpersonal dysregulation—relationships are typically intense, chaotic, and difficult (Robins et al., 2001). One explanation for the interpersonal problems suggests that they arose in childhood—that family members and friends were likely to invalidate the patient’s experience (Linehan, 1993). For instance, a parent might tell a child, “You’re too sensitive” or “You’re overreacting.” During childhood, such chronic dismissals may have led to fear of rejection and abandonment, if not actual rejection. Such experiences may have sensitized the child, leading him or her subsequently to overreact to the slightest hint of being invalidated.

In addition, this interpersonal dysregulation may arise in part because of patients’ emotional and cognitive dysregulation (Fonagy & Bateman, 2008). When people with borderline personality disorder meet someone who is positive or helpful, they often begin by depending on that person to help calm their emotions, as Reiland did with her husband. But, paradoxically, once they feel dependent, they fear being abandoned—which leads them to behave in ways likely to lead to rejection. Friends and family members may come to respond with caring and concern only when the patient exhibits self-destructive behaviors (which, in turn, inadvertently reinforces those behaviors).

Feedback Loops in Understanding Borderline Personality Disorder

Linehan’s (1993) model of borderline personality disorder rests on a series of feedback loops (like those illustrated in Figure 13.2): Some children have brain systems (neurological factor) that lead them to have extreme emotional reactions (psychological factor), and their parents may have difficulty soothing them (social factor) when they are emotionally aroused (Graybar & Boutelier, 2002; Linehan, 1993). Either because the parents create an invalidating environment (“It’s not as bad as you’re making it out to be”; social factor) or because they engage in outright abuse or neglect (as occurred with Reiland), the children may become insecurely attached to their parents. In turn, the children don’t learn to regulate their emotions or behaviors (and cognitions) and elicit untoward reactions from others, which then confirms their view of themselves and others.

This invalidating process, according to Linehan, leaves the person feeling punished for his or her thoughts, feelings, and behaviors—they are trivialized, dismissed, disrespected (Linehan & Kehrer, 1993). Such people therefore have a hard time identifying and labeling their emotions accurately and coming to trust their own experiences and perceptions as valid (psychological factor). They don’t learn effective problem solving or ways to cope with distress.

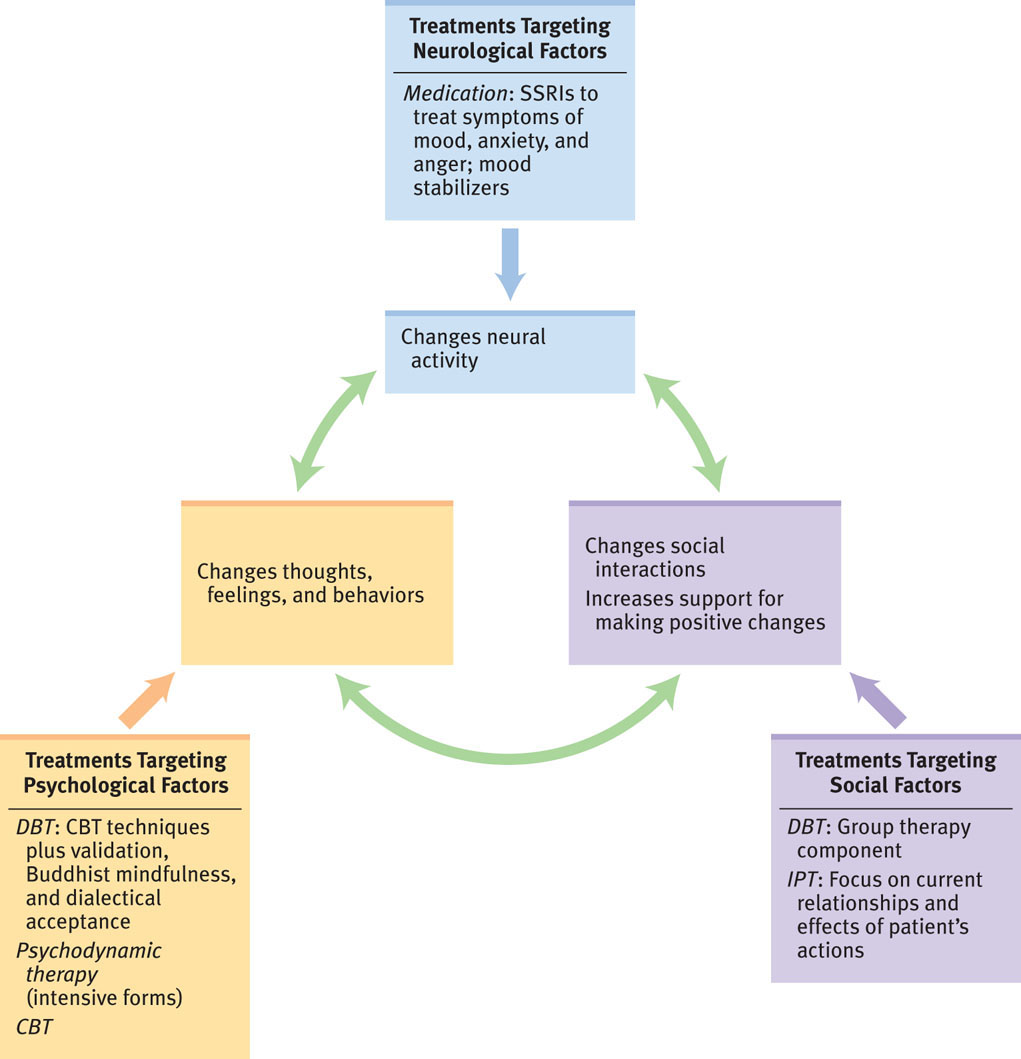

Treating Borderline Personality Disorder: New Treatments

Borderline personality disorder is among the most challenging personality disorders to treat (Robins et al., 2001), in part, because of the patient’s parasuicidal or suicidal thoughts and behaviors. It can also be challenging because of the intense anger that a patient may direct at the mental health clinician. In what follows we examine the various targets of treatment—neurological factors, psychological factors, and social factors—and pay particular attention to a comprehensive psychological treatment that is the treatment of choice: dialectical behavior therapy.

Targeting Neurological Factors: Medication

Various medications may be prescribed to people with borderline personality disorder for a comorbid non-personality disorder or to target certain symptoms, including quickly changing moods, anxiety, impulsive behavior, and psychotic symptoms (Lieb et al., 2004). An SSRI—compared to a placebo—may diminish symptoms of emotional lability and anxiety and help with anger management. In addition, antipsychotics can alleviate psychotic symptoms, and mood stabilizers may help some symptoms (Binks et al., 2006a). Although medications may reduce the intensity of some symptoms, medications have limited effect and should not be the only form of treatment for people with borderline personality disorder (Koenigsberg et al., 2007).

Targeting Psychological Factors: Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Marsha Linehan, a pioneer in the treatment of borderline personality disorder, initially treated such patients with CBT, which focuses on identifying and correcting irrational thoughts and faulty beliefs (Beck et al., 2004; Linehan, 1993)—but this led some people to drop out of treatment because they felt that the focus on changing their thoughts and beliefs implicitly criticized and invalidated them (Dimeff & Linehan, 2001). In response, Linehan (1993) developed a new treatment for people with borderline personality disorder. From CBT she incorporated skill development and cognitive restructuring. In addition, in her new therapy, she underscored the importance of a warm and collaborative bond between patient and therapist; to this mix she added the following elements:

- An emphasis on validating the patient’s experience. That is, the patient’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in a given situation make sense in the context of his or her life, past experiences, and strengths and weaknesses.

- A Zen Buddhist approach. Patients should see, and then without judgment, accept any painful realities of their lives. Patients are encouraged to “let go” of emotional attachments that cause them suffering. Mindfulness, or nonjudgmental awareness, is the goal (Perroud et al., 2012).

- A dialectics component. Dialectics refers to a synthesis of opposing elements; in this context, it refers to the patient’s coming to accept the situation and aspects of it that he or she does not feel able to change (e.g., validating his or her experience) while at the same time recognizing that in order to feel better, change must occur (Robins et al., 2001).

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) A form of treatment that includes elements of CBT as well as an emphasis on validating the patient’s experience, a Zen Buddhist approach, and a dialectics component.

Linehan called this treatment dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and it entails both group and individual therapy. The initial priority of DBT is to reduce self-harming behaviors such as burning or cutting oneself. As these behaviors are reduced, treatment focuses on other behaviors that interfere with therapy and with the quality of life. Therapy also helps patients develop skills to change what can be changed: their own behavior rather than the behavior of other people, such as family members. In addition, treatment helps patients to recognize aspects of their lives that they can’t change: For instance, although patients can learn to change the way they behave toward their parents, they can’t change the way their parents behave toward them. Treatment lasts about 1 year.

Researchers have conducted many studies to evaluate DBT and have noted impressive results for patients with borderline personality disorder: DBT does decrease suicidal thoughts and behaviors and leads to lower dropout and hospitalization rates—and it does so more effectively than other specialized treatments for this disorder (Binks et al., 2006b; Linehan et al., 2006). DBT has been adapted to treat people with other psychological disorders that involve impulsive symptoms, such as bulimia (Palmer et al., 2003).

Intensive forms of psychodynamically oriented psychotherapy have also been shown to be effective for patients with borderline personality disorder (Clarkin et al., 2007; Gregory & Remen, 2008). Similarly, research indicates that cognitive therapy and CBT can be effective (Davidson et al., 2006; Wenzel et al., 2006).

Targeting Social Factors: Interpersonal Therapy

Interpersonal therapy (IPT) has been adapted to treat borderline personality disorder. The goal of IPT for this personality disorder is to help the patient develop more adaptive interpersonal skills so that he or she feels and functions better. This therapy tries to help patients integrate their extreme but opposed feelings about a person: When they talk about feeling one way about someone (“He’s perfect”), the therapist tries to discuss opposite feelings as well, underscoring that no individual is all good or all bad (Markowitz, 2005; Markowitz et al., 2006). A course of IPT for borderline personality disorder typically lasts about 8 months. Social interactions are also a focus of the group therapy component of DBT.

Feedback Loops in Treating Borderline Personality Disorder

Successful treatment of borderline personality disorder may target more than one factor; positive changes in any factor, though, affect other factors via feedback loops (see Figure 13.3). For example, one goal of DBT is to help patients regulate their emotions (psychological factor). When the therapy is successful, better emotional regulation allows patients to calm themselves more effectively when they are anxious or angry, which directly affects brain mechanisms (neurological factor) and in turn makes their relationships less volatile (social factors). Similarly, the honest and caring feedback from others within the therapeutic environment (part of DBT, IPT, CBT, and intensive psychodynamic therapy) challenges patients to alter their behaviors and ways of thinking about themselves and their relationships (psychological and social factors), which in turn decreases their emotional reactivity (neurological and psychological factors).

Histrionic Personality Disorder

Histrionic personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by attention-seeking behaviors and exaggerated and dramatic displays of emotion.

You may know someone who initially seemed charming, open, enthusiastic—maybe even flirtatious. After a while, did he or she seem to go to great lengths to be the center of attention, behaving too dramatically? Did the person have temper tantrums, sobbing episodes, or other dramatic displays of emotion that appeared to turn on and off like a light switch? These are the qualities of people with histrionic personality disorder, who seek attention and exaggerate their emotions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Rachel Reiland relates her desire to be the center of attention:

I wanted to be the entire focus of any person I was obsessed with. My incessant hunger for attention had been a part of my life for as long as I could remember. The burning heartache of emptiness obsessed me even when my peers had been taken with Barbie dolls and coloring books. I knew even then that these constant feelings were not normal….

When the object of my longing—the teacher, the coach, the boss—was present in the room, I geared everything to that person. I contrived every word, action, inflection, and facial expression for him. Does he see me laughing? Does he see how funny everybody thinks I am?

(2004, pp. 335–336)

Reiland’s behavior involved some features of histrionic personality disorder; in what follows we examine the disorder in more detail.

What Is Histrionic Personality Disorder?

TABLE 13.14 lists the diagnostic criteria for histrionic personality disorder. Beyond the overt attention seeking and dramatic behavior, people with histrionic personality disorder may exhibit more subtle symptoms: When they feel bored or empty, they seek out novelty and excitement; they may have difficulty delaying gratification and tend to become easily and excessively frustrated by life’s challenges. Being in long-term relationships with people with histrionic personality disorder can be challenging because they usually don’t recognize their symptoms—they don’t feel as though they are overreacting or being overly dramatic or seductive, although they clearly are. Case 13.7 presents a woman with this personality disorder and TABLE 13.15 provides additional facts about the personality disorder.

A pervasive pattern of excessive emotionality and attention seeking, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source is American Psychiatric Association, 2000, 2013. |

CASE 13.7 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Histrionic Personality Disorder

A 23-year-old single woman was referred for a psychological assessment by her gynecologist. The patient had been described as “outgoing, effusive, and ‘dressed to kill’.”

She had been experiencing debilitating pain for over half a year, but the pain seemed to be medically unexplainable. Throughout the interview, she used facial and other nonverbal expressiveness to dramatize the meaning of her words. In describing her pain, for example, she said she felt as though “I will absolutely expire” as she closed her eyes and dropped her head forward to feign death. However, when asked about her pain, she became coquettish and was either unable or unwilling to provide details. She talked freely about topics tangential to the interview, skipping quickly from topic to topic and periodically inserting sexual double entendres. She described her family as happy and well-adjusted but acknowledged conflict with her mother and complained that her older brothers treated her like a baby…. She was not currently in a serious relationship, but stated with a giggle that most boys “find me very attractive,” adding that they “just want me for my body.”…At the time of the interview, she was working as a dancer at an adult club; she particularly liked the attention and the money that the job provided.

(Millon & Davis, 2000, p. 237; quoted in Horowitz, 2004, p–191)

Distinguishing Between Histrionic Personality Disorder and Other Disorders

Although people with antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, and histrionic personality disorder are all manipulative and impulsive, their motivations differ: People with histrionic personality disorder desire frequent attention from others; people with antisocial personality disorder seek power or material gain; and people with borderline personality disorder want nurturance (Skodol, 2005). Moreover, although both histrionic and borderline personality disorders involve rapidly shifting emotions, only with the latter are the emotions usually related to anger.

Reiland’s behavior fit some of the criteria for histrionic personality disorder, in that some of her dramatic displays seemed to be motivated by a desire for attention. She might be diagnosed with histrionic personality disorder as a comorbid disorder; however, the elements of her behavior that indicate borderline personality disorder overshadow the features of histrionic personality disorder. A clinician trying to make a definitive diagnosis (or diagnoses) would want to find out more about any thoughts, feelings, or behaviors that might indicate or rule out histrionic personality disorder. Little formal research has been conducted that illuminates factors that contribute to this personality disorder, and so we next focus on how to treat this personality disorder.

Treating Histrionic Personality Disorder

A goal of treatment for histrionic personality disorder is to help patients recognize and then modify their maladaptive beliefs and strategies. Specifically, using techniques from CBT or psychodynamic therapy, the therapist tries to help patients increase their capacity to cope with distress, develop more adaptive ways of responding to frustration, recognize the negative impact that their actions have on their relationships, and shift their view of themselves and other people (Beck et al., 2004; Farmer & Nelson-Gray, 2005). Like other patients with dramatic/erratic personality disorders, those with histrionic personality disorder often do not remain in treatment for long; they become bored or frustrated and continue to see other people as the primary problem.

Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Unlike antisocial and borderline personality disorders, narcissistic personality disorder does not involve impulsiveness or self-destructive tendencies but rather a sense of grandiosity.

What Is Narcissistic Personality Disorder?

Narcissistic personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by an inflated sense of self-importance, an excessive desire to be admired, and a lack of empathy.

People with narcissistic personality disorder have an inflated sense of their own importance; they expect—and demand—praise and admiration, and they lack empathy (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This sense of self-importance, however, masks mixed feelings. On the one hand, they are preoccupied with their own concerns and expect others to be as well, and they get angry when other people don’t defer to them. They overvalue themselves and undervalue other people, which is true of Patricia in Case 13.8. On the other hand, their self-esteem can be fragile, leading them to fish for compliments. They are relatively insensitive to others’ feelings and points of view. TABLE 13.16 lists the diagnostic criteria for narcissistic personality disorder, and TABLE 13.17 presents additional information about this disorder.

A pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration, and lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

CASE 13.8 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Patricia was a 41-year-old married woman who presented at an outpatient mental health clinic complaining of interpersonal difficulties at work and recurring bouts of depression. She described a series of jobs in which she had experienced considerable friction with coworkers, stating that people generally did not treat her with the respect she deserved…. Shortly before her entrance into treatment, Patricia was demoted from a supervisory capacity at her current job because of her inability to effectively interact with those she was supposed to supervise. She described herself as always feeling out of place with her coworkers and indicated that most of them failed to adequately appreciate her skill or the amount of time she put in at work. She reported that she was beginning to think that perhaps she had something to do with their apparent dislike of her. Patricia stated several times…that the tellers at the bank were jealous of her status and abilities as a loan officer and that this made them dislike her.

(Corbitt, 2002, pp. 294–295)

Note that Patricia, in Case 13.8, said that people didn’t treat her with the respect that she felt she deserved and that she didn’t feel adequately appreciated; people with narcissistic personality disorder often report such feelings. Reiland’s symptoms do not meet the criteria for a diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder; her problematic behaviors were often impulsive and self-destructive, and she did not have a stable, inflated sense of self.

As is true for histrionic personality disorder, very little research illuminates factors that contribute to narcissistic personality disorder—and so we move directly to examine ways to treat narcissistic personality disorder.

Treating Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Treatment for narcissistic personality disorder is basically the same as treatment for histrionic disorder: The therapist seeks to help patients recognize and then modify their maladaptive beliefs and strategies, using techniques of CBT or psychodynamic therapy. However, as for all patients with personality disorders, those with narcissistic personality disorder usually do not remain in treatment for long—and typically continue to see other people as the primary problem rather than their own beliefs or behaviors.

Thinking Like A Clinician

In high school and college, Will acted in school plays. Now in his 30s, he travels a lot, making presentations for his job, and so has a lot of independence. He likes the freedom of not having a boss looking over his shoulder all the time, and he enjoys making presentations. Because no one really knows how many hours he works, he sometimes starts late in the morning or quits early; then he heads for a bar to down a few beers. Occasionally, he takes whole days off’ after he’s had too much to drink the night before. He’s been through a series of girlfriends, never staying with one for more than 6 months. Lately, though, his single status has been bothering him, and he’s been wondering why there don’t seem to be any decent women out there.

In what ways does Will seem typical of someone with a Cluster B (dramatic/erratic) personality disorder? In what ways is he unusual? What would you need to know before you could decide whether he had a dramatic/erratic personality disorder? Which specific personality disorder seems most likely from the description of him, and why? Why is—or isn’t—this information enough to make a diagnosis?