8.3 Infancy and Child Development

26 AND PREGNANT

The circumstances surrounding the birth of Jasmine’s second child were strikingly different from those of her first. When Eddie came into the world, Jasmine was a married, working woman with 10 more years of life experience; and a decade can make a world of difference in development. As Jasmine can testify, “The mental capacity is way different between a 16- and a 26-year-old.” By this time in life, Jasmine had become much more aware of how her decisions impacted others, especially her children.

The circumstances surrounding the birth of Jasmine’s second child were strikingly different from those of her first. When Eddie came into the world, Jasmine was a married, working woman with 10 more years of life experience; and a decade can make a world of difference in development. As Jasmine can testify, “The mental capacity is way different between a 16- and a 26-year-old.” By this time in life, Jasmine had become much more aware of how her decisions impacted others, especially her children.

Being pregnant with Eddie was nothing like the carefree experience of carrying Jocelyn. Jasmine noticed every ache and pain, and her nausea was so severe that she lost 20 pounds during the first few months. About midway into the pregnancy, doctors put her on strict bed rest in an effort to prevent a premature delivery, but Eddie still arrived 9 weeks early. In developed countries like the United States, the age of viability, or the earliest point at which a baby can survive outside of the mother’s womb, has dropped to 22 weeks gestational age (Lawn et al., 2011).

During the fetal stage, the digestive, respiratory, and other organ systems become fully developed. For babies born early, those systems may not be fully prepared to function. Eddie needed a breathing tube, a feeding tube, and an incubator because he could not yet control his body temperature. For a week following his delivery, Jasmine could only make contact by sticking her hands through a hole in his incubator. When she finally did get to hold Eddie, his response was breathtaking. Not only did he stop fussing and whining, he reacted with measurable physiological changes. “His vital signs went up,” Jasmine says. “He breathed better on his own.”

Kangaroo Care

Physical closeness can have a profound impact on parents and babies alike. Preemie mothers such as Jasmine who “kangaroo,” or have close skin-to-skin contact with their babies in the hospital, report less depression and may become more attuned to their babies’ needs than those who do not. Their babies in turn may have an advantage over their preterm peers in terms of cognitive and motor development (Feldman, Eidelman, Sirota, & Weller, 2002; Feldman, Weller, Sirota, & Eidelman, 2002). Premature babies who receive this type of attention also have shorter stays in the hospital and an easier time learning how to nurse (Gregson & Blacker, 2011). Touch is very important to preterm infants, which is evident in its clear link with weight gain (Field, 2001). Whether premature or full-term, there is evidence that some infants cry less and sleep better when they have plenty of skin-to-skin contact with parents, but the amount of tactile stimulation varies from culture to culture. Infant massage is unheard of in some parts of the world, but is a daily practice in India, Bangladesh, and China (Underdown, Barlow, & Stewart-Brown, 2010).

Newborn Growth and Development

LO 7 Summarize some developmental changes that occur in infancy.

Newborn babies exhibit several reflexes, or unlearned patterns of behavior. Some are necessary for survival; others do not serve any obvious purpose. A few fade away in the first weeks and months of life, but many will resurface as voluntary movements as the infant grows and develops motor control (Thelen & Fisher, 1982). Let’s take a look at two of these reflexes.

Rooting and Sucking Reflexes

What does a newborn do when you stroke its cheek? She opens her mouth and turns her head in the direction of your finger, apparently in search of a nipple. This rooting reflex typically disappears at 4 months, never to be seen again. The sucking reflex, evident when you touch her lips, also appears to be a feeding reflex. Sucking and swallowing abilities don’t fully mature until the gestational age of 33 to 36 weeks, so babies who are born before that time—like Jasmine’s son Eddie—may struggle with feeding (Lee et al., 2011). But that doesn’t mean they cannot enjoy the benefits of breast milk, which is thought to have important effects on growth and cognitive development (Chaimay, 2011; de Lauzon-Guillain et al., 2012; Horwood & Fergusson, 1998). Jasmine pumped her breast milk, making it possible for Eddie to get its nutritional benefits through his feeding tube.

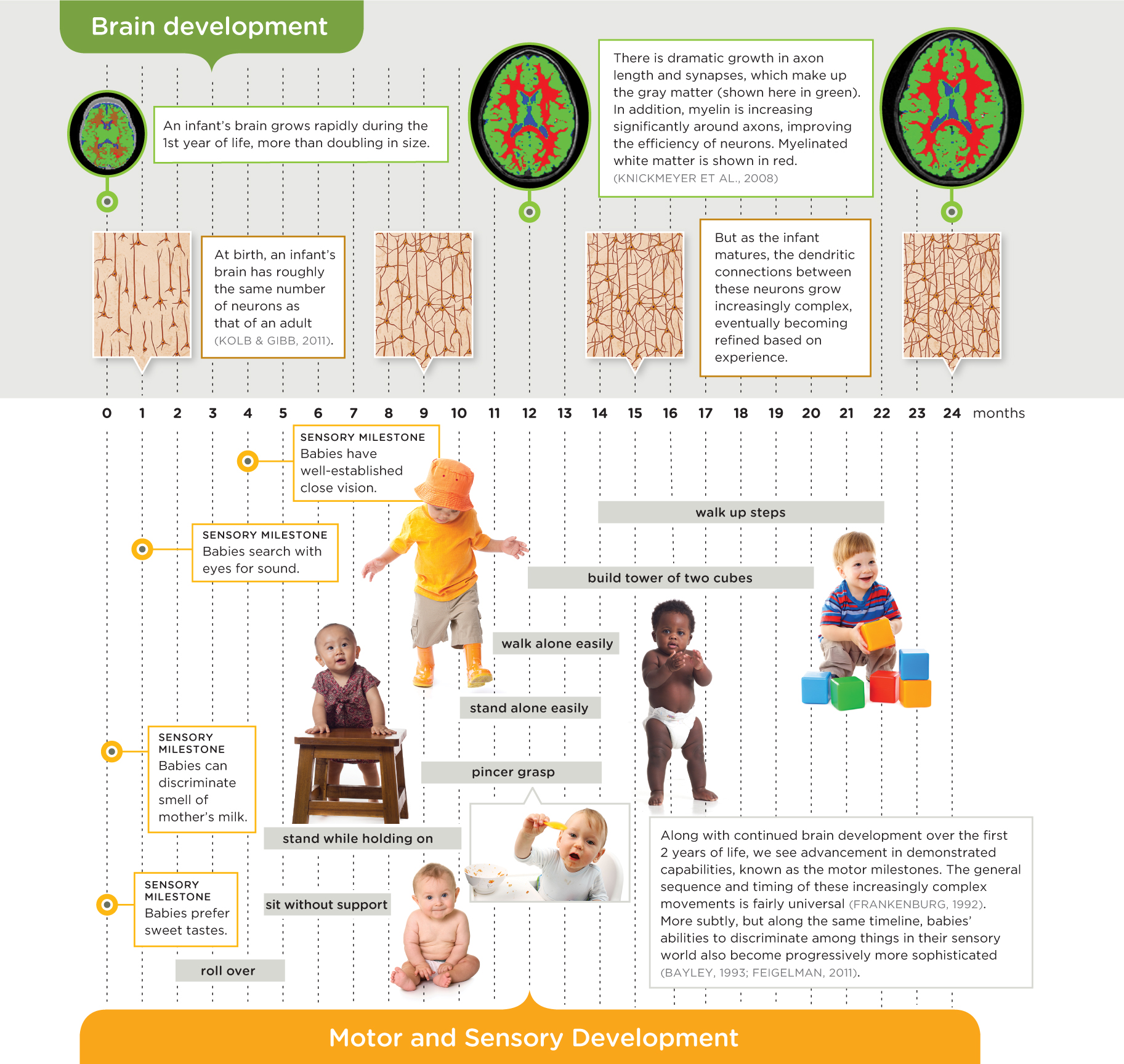

A newborn spends most of its time eating, sleeping, and crying. Sounds like a simple routine, but waking every 2 to 3 hours to feed a wailing baby can be very exhausting. Nevertheless, this stage soon gives way to a period of change that is far more interactive, and includes waving, clapping, walking, and dangerous furniture climbing. Infographic 8.2 details some of the sensory and motor milestones of infancy. Keep in mind that the listed ages are averages; significant variation does exist across infants. The general sequence and timing, however, are fairly universal.

The Newborn Senses

Babies come into the world equipped with keen sensory capabilities that seem to be designed for facilitating relationships. For example, infants prefer to look at human faces as opposed to geometric shapes (Salva, Farroni, Regolin, Vallortigara, & Johnson, 2011). They can discriminate their mother’s voice from those of other women within hours of birth, and they show a preference for her voice (DeCasper & Fifer, 1980). Jocelyn emerged from the womb crying but calmed down instantly when placed in Jasmine’s arms. It was as if she already knew the sound of her mother speaking and singing. And she very well might have; studies suggest that babies do indeed come to recognize their mothers’ voices while in the womb (Kisilevsky et al., 2003; Sai, 2005). Hearing is developed and functioning before a baby is born, but sounds are initially distorted. It takes some time for amniotic fluid to dry up completely before a baby can hear clearly (Hall, Smith, & Popelka, 2004).

Smell, taste, and touch are also well developed in newborn infants. These tiny babies can distinguish the smell of their own mothers’ breast milk from that of other women within days of birth (Nishitani et al., 2009). Babies prefer sweet tastes, react strongly to sour tastes, and notice certain changes to their mothers’ diets because those tastes are present in breast milk. If a mother eats something very sweet, for instance, the infant tends to breast-feed longer.

The sense of touch is evident before birth; as early as 2 months after conception, for example, a fetus will show the rooting reflex. It was once believed that newborns were incapable of experiencing pain. But research suggests otherwise. Newborns respond to pain with reactions similar to those of older infants, children, and adults (Gradin & Eriksson, 2011; Urso, 2007).

Sight is the weakest sense in newborns, who have difficulty seeing things that are not in their immediate vicinity. The optimal distance for a newborn to see an object is approximately 8–14 inches away from his face (Cavallini et al., 2002), which happens to be the approximate distance between the face of a nursing baby and his mother. Eye contact is thought to strengthen the relationship between mother and baby. A newborn’s vision can be blurry for several months, one reason being that the light-sensitive cones in the back of the eye are still developing (Banks & Salapatek, 1978).

The Growing Brain

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we reported that cones are specialized neurons called photoreceptors, which absorb light energy and turn it into chemical and electrical signals for the brain to process. Cones enable us to see colors and details. Newborns have blurry eyesight in part because their cones have not fully developed.

The speed of brain development in the womb and immediately after birth is astounding. There are times in fetal development when the brain is producing some 250,000 new neurons per minute! The creation of new neurons is mostly complete by the end of the 5th month of fetal development (Kolb & Gibb, 2011). At the time of birth, a baby’s brain has approximately 100 billion neurons (Toga, Thompson, & Sowell, 2006)—roughly the same number as that of an adult. Meanwhile, axons are growing longer, and more neurons—particularly those involved in motor control—are developing a myelin sheath around their axons. The myelin sheath increases the efficiency of neural communication, which leads to better motor control, enabling a baby to reach the milestones described earlier (waving, walking, and so forth).

INFOGRAPHIC 8.2: Infant Brain and Sensorimotor Development

As newborns grow, they progress at an astounding rate in seen and marvel at how far they have come. But what you can’t see is the real unseen ways. When witnessing babies’ new skills, whether it be reaching action. These sensorimotor advancements are only possible because of for a rattle or pulling themselves into a standing position, it’s easy to the incredible brain development happening in the background.

Synaptic Pruning

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described the structure of a typical neuron, which includes an axon projecting from the cell body. Many axons are surrounded by a myelin sheath, which is a fatty substance that insulates the axon. This insulation allows for faster communication within and between neurons. Here we see how this impacts motor development.

Neurons rapidly sprout new connections among each other, a dramatic phase of synaptic growth that is influenced by the infant’s experiences and stimulation from the environment. The increase in connections is not uniform throughout the brain. Between the ages of 3 and 6, for example, the greatest increase in neural connections occurs in the frontal lobes, the area of the brain involved in planning and attention (Thompson et al., 2000; Toga et al., 2006). As more links are established, more associations can be made between different stimuli, and between behavior and consequences. A young person needs to learn quickly, and this process makes it possible.

However, the extraordinary growth in synaptic connections does not last forever, as their number decreases by 40 to 50% by the time a child reaches puberty (Thompson et al., 2000; Webb, Monk, & Nelson, 2001). In a process known as synaptic pruning, unused synaptic connections are downsized or eliminated (Chechik, Meilijson, & Ruppin, 1998).

Rosenzweig’s Rats

Synaptic pruning and other aspects of brain development are strongly influenced by experiences and input from the outside world. In the 1960s and 1970s, Mark Rosenzweig and his colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley, demonstrated how much environment can influence the development of animal brains (Kolb & Whishaw, 1998). In one study, the researchers placed young rats in three different settings: (1) enriched environments, or cages with other rats and a variety of toys and interesting objects; (2) standard colony cages, which contained no stimulating objects; and (3) isolation cages with no playthings or companions (Barredo & Deeg, 2009, February 24; Rosenzweig, 1984). Rats reared in the enriched condition experienced greater increases in brain weight and synaptic connections compared to rats in the nonstimulating environments (Kolb & Whishaw, 1998).

try this

Identify the independent and dependent variables in the Rosenzweig study that examined the changes in brain development associated with three living conditions.

Independent variable: level of environmental stimulation (enriched environment, standard colony cages, or isolation cages). Dependent variable: changes in brain development.

How does this research on lab rats relate to human development? Isolation and lack of stimulation may also put a damper on the brain development of infants and children. Some research suggests that orphanage-raised babies who have received minimal care and human interaction experience delays in cognitive, social, and physical development. There is, however, a great deal of variability in later development when the children are placed in adoptive homes (Rutter & O’Connor, 2004).

The Language Explosion

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we introduced the basic elements of language, such as phonemes, morphemes, and semantics. We also introduced some basic theories of language development. In this chapter, we discuss how language develops in humans.

The brain development that occurs during childhood and the cognitive changes associated with it are critical. Consider the fact that babies come into the world incapable of using language, yet by the age of 6, most have amassed a vocabulary of about 13,000 words (Pinker, 1994). The development of language is a remarkable feat. Let’s take a look at some of the theories that attempt to explain it.

Behaviorism and Language

LO 8 Describe the theories explaining language acquisition.

Behaviorists propose that all behavior—including the use of language—is learned through associations, reinforcers, and observation. Infants and children learn language in the same way they learn everything else, through positive attention to correct behavior (for example, praising correct speech), unpleasant attention to incorrect behavior (for example, criticizing incorrect speech), and the observation of others.

Chapter 5 presented the principles of learning. Here, we see how operant conditioning, through reinforcement and punishment, and observational learning, through modeling, can be used to understand how language is acquired.

Language Acquisition Device

But the behaviorist theory may not explain all the complexities of language acquisition. If a young child tries to imitate a particular sentence structure, such as “I am going to the kitchen,” he might instead say something grammatically incorrect, “I go kitchen.” Children are not directly taught the structure of grammar, because its rules are too difficult for their developing brains to understand. Linguist Noam Chomsky (1959) suggested humans have a language acquisition device (LAD) that provides an innate mechanism for learning language. With the LAD, children compare the language they hear in their environment to a framework already hardwired in their brains. The fact that children all over the world seem to learn language in a fixed sequence, and during approximately the same sensitive period, is evidence that this innate language capacity may exist.

Infant-Directed Speech (IDS)

More recent theories of language acquisition focus on parents’ and other caregivers’ use of infant-directed speech (IDS). High-pitched and repetitious, IDS is observed throughout the world (Singh, Nestor, Parikh, & Yull, 2009). Can’t you just hear Jasmine saying to baby Jocelyn in a high-pitched, sing-song voice, “Who’s my little girl?” Researchers report that infants as young as 5 months old pay more attention to people who use IDS, which allows them to choose “appropriate social partners,” or adults who are more likely to provide them with chances to learn and interact (Schachner & Hannon, 2011).

Language in the Environment

It’s not only the type of voice that matters but also the amount of talking. Infants may not be the best conversation partners, but they benefit from a lot of chatter. It turns out that the amount of language spoken in the home correlates with socioeconomic status. Children from high-income families are more likely to have parents who engage them in conversation. Just look at these numbers for parents of toddlers: 35 words a minute spoken by high-income parents; 20 words a minute spoken by middle-income parents; 10 words a minute spoken by low-income parents (Hoff, 2003). The consequences of such interactions are apparent, with toddlers from high-income households having an average vocabulary of 766 words, and those from low-income homes only 357 (Hart & Risley, 1995). How might this disparity impact these same children when they start school? Research suggests that children from lower socioeconomic households begin school already lagging behind in reading, math, and academic achievement in general (Lee & Burkan, 2002), all skills that could potentially be linked to decreased verbal interactions.

The Sequence of Acquisition

LO 9 Examine the universal sequence of language development.

Coo. Babble. Talk. No matter what language infants speak, or who raises them, you can almost be certain they will follow the universal sequence of language development (Chomsky, 2000). At the age of 2 to 3 months, infants typically start to produce vowel-like sounds known as cooing. These “oooo” and “ahhh” sounds are often repeated in a joyful manner. Jasmine’s children tended to coo in response to specific stimuli. For Jocelyn, it was the sound of people talking; for Eddie, the appearance of colorful images.

When infants reach the age of 4 to 6 months, they begin to combine consonants and vowels in the babbling stage. These sounds are meaningless, but babbling can resemble real language (“ma, ma, ma, ma, ma” Did you say…mama?). Jasmine distinctly remembers Jocelyn as a tiny infant repeating “da, da, da, da,” as if she were saying “Dadda” over and over. Amused by the irony of the situation (Jasmine was a single mother), she would put her face close to Jocelyn’s and repeatedly say, “ma, ma, ma, ma.” Eventually, Jocelyn did say the word “mama,” but it took several months. Nonhearing infants also go through this babbling stage, but they move their hands instead of babbling aloud (Petitto & Marentette, 1991). For both hearing and deaf infants, the babbling stage becomes an important foundation for speech production; when infants babble, they are on their way to their first words.

When do real words begin? At around 12 months, infants typically begin to utter their magical first words. Often, these are nouns used to convey an entire message, or holophrase. Perhaps you have heard an infant say something emphatically, such as “JUICE!” or “UP!” What she might be trying to say is “I am thirsty, could I please have some juice?” or “I want you to pick me up.”

At about 18 months, infants start to use two-word phrases in their telegraphic speech. These brief statements might include only the most important words of a sentence, such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives, but no prepositions or articles. “Baby crying” might be a telegraphic sentence meaning the baby at the next table is crying loudly. Jocelyn’s first two-word phrase was “Stop it!” Jasmine suspects that she was the one who schooled her daughter in this phrase. As a teenage mom, she had not yet developed the patience that she would have in her twenties and thirties.

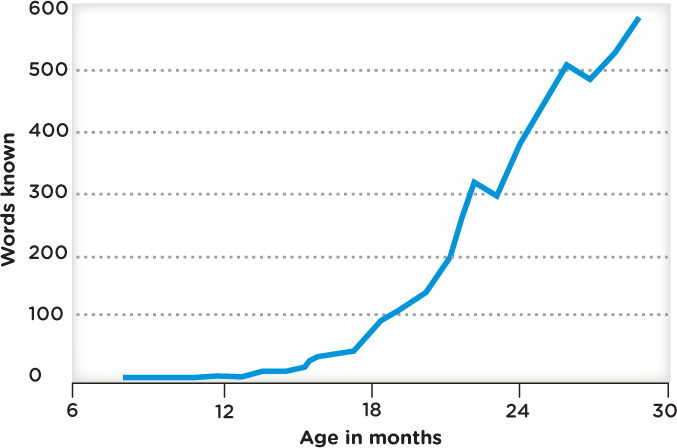

As children mature, they start to use more complete sentences. Their grammar becomes more complex and they pack more words into statements. A “vocabulary explosion” tends to occur around 2 to 3 years of age (McMurray, 2007; Figure 8.3). By 5 to 6, most children are fluent in their native language, although their vocabulary does not match that of an adult.

There are two important components of normal language development: (1) physical development, particularly in the language-processing areas of the brain (Chapter 2); and (2) exposure to language. If a child does not observe people using language during the first several years of life, normal language skills will not develop. Evidence for this phenomenon comes from case studies of people who have suffered damage to the brain after the critical period or were deprived of language in childhood (Goldin-Meadow, 1978). One of the most well-documented—and deeply troubling—cases of childhood deprivation centers on a young girl known as Genie.

THINK again

Genie the “Feral Child”

In 1970 a social worker in Arcadia, California, discovered a most horrifying case of child neglect and abuse. “Genie,” as researchers came to call her, was 13 at the time her situation came to the attention of the authorities, though she barely looked 7. Feeble and emaciated, the child could not even stand on two feet. Genie was neither potty-trained nor capable of chewing food. She could not even speak (Curtiss, Fromkin, Krashen, Rigler, & Rigler, 1974; PBS, 1997, March 4).

In 1970 a social worker in Arcadia, California, discovered a most horrifying case of child neglect and abuse. “Genie,” as researchers came to call her, was 13 at the time her situation came to the attention of the authorities, though she barely looked 7. Feeble and emaciated, the child could not even stand on two feet. Genie was neither potty-trained nor capable of chewing food. She could not even speak (Curtiss, Fromkin, Krashen, Rigler, & Rigler, 1974; PBS, 1997, March 4).

Between the ages of 20 months and 13 years, Genie had been locked away in a dark room, strapped to a potty chair or confined in a cagelike crib. Her father beat her when she made any type of noise. There, Genie stayed for 12 years, alone in silence, deprived of physical activity, sensory stimulation, and affection (Curtiss et al., 1974).

When discovered and brought to a hospital at age 13, Genie would not utter a sound (Curtiss et al., 1974). She did seem to understand simple words, but that was about it for her language comprehension. Researchers tried to build Genie’s vocabulary, teaching her basic principles of syntax, and she made considerable gains, eventually speaking meaningful sentences. But some aspects of language, such as the ability to use the passive tense (“The carrot was given to the rabbit”) or words such as “what” and “which” continued to mystify her (Goldin-Meadow, 1978). Why couldn’t Genie master certain linguistic skills? Was it because she missed a critical period for language development?

AT AGE 13, GENIE COULD NOT EVEN SPEAK.

This is a real possibility. Similar outcomes have been observed in other “feral” children. Consider the example of 6-year-old Danielle Crockett of Florida, who was discovered living among cockroaches and excrement in her mother’s closet in 2005. Danielle was removed from that home and later adopted by a loving family, but her speech therapist is not sure she will ever develop the ability to speak (DeGregory, 2008). There are other variables to consider in the Genie case, like the possibility that she may have suffered from an underlying intellectual disability, or that she never developed the throat muscles required for normal speech (Curtiss et al., 1974; James, 2008, May 7). We should note that Genie’s story does end with a glimmer of hope. Genie is reported to be “happy,” living in a group home for adults with intellectual disabilities (James, 2008, May 7).

Piaget and Cognitive Development: Blossoming of a Young Mind

LO 10 Summarize the constructs of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.

Language is just one domain of cognitive development. How do other processes like memory and problem solving evolve through childhood? As noted earlier, psychologists do not always agree on whether development is continuous or occurs in steps. Swiss biologist and developmental psychologist Jean Piaget (pyä-′zhā 1896–1980) was among the first to suggest that infants have cognitive abilities, a notion that was not widely embraced at the time. Children do not think like adults, suggested Piaget, and their cognitive development takes place in stages.

One of the basic units of cognition, according to Piaget (1936/1952), is the schema, a collection of ideas or notions representing a basic unit of understanding. Young children form schemas based on functional relationships. The schema “toy,” for example, might include any object that can be played with (such as dolls, trucks, and balls). As children mature, so do their schemas, which begin to organize and structure their thinking around more abstract categories, such as “love” (romantic love, love for one’s country, and so on). As they grow, children expand their schemas in response to life experiences and interactions with the environment.

Piaget (1936/1952) believed humans are biologically driven to advance in intellectual development, partly as a result of an innate need to maintain cognitive equilibrium, or a feeling of mental or cognitive balance. Suppose a kindergartener’s schema of airplane pilots includes only men, but then he sees a female pilot on television. This experience shakes up his notion of who can be a pilot, causing an uncomfortable sense of disequilibrium that motivates him to restore cognitive balance. There are two ways he might accomplish this. He could use assimilation, an attempt to understand new information using his already existing knowledge base, or schema. For example, the young boy might think about the female bus drivers he has seen and connect that to the female pilot idea (Women drive buses, so maybe they can fly planes too). However, if the new information is so disconcerting that it cannot be assimilated, he might use accommodation, a restructuring of old notions to make a place for new information. With accommodation, we remodel old schemas or create new ones. If the child had never seen a female driving anything other than a car, he might become confused at the sight of a female pilot. To eliminate that confusion, he could create a new schema. This is how we make great strides in cognitive growth. We assimilate information to fit new experiences into our old ways of thinking, and we accommodate our old way of thinking to understand new information.

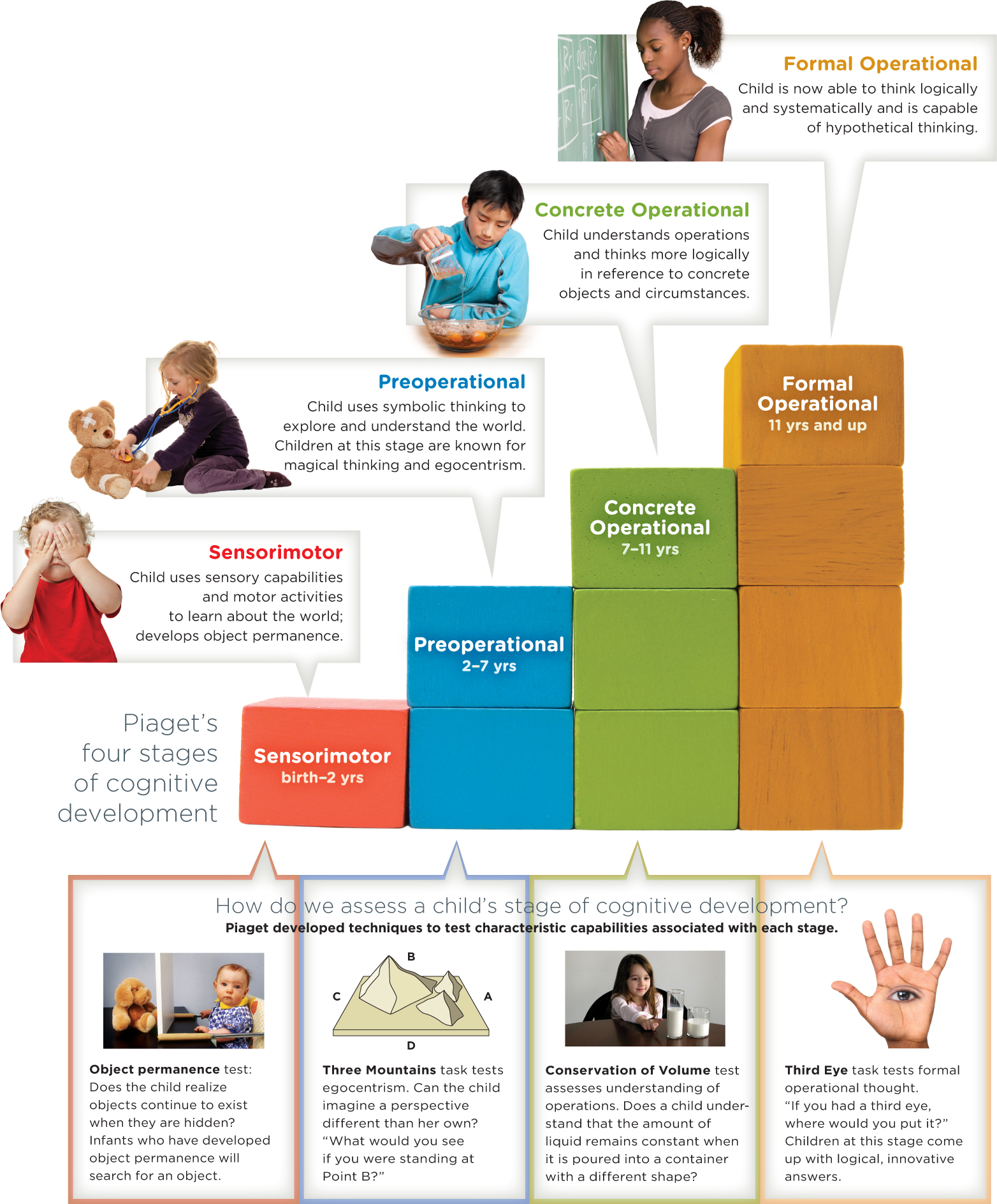

Piaget (1936/1952) also proposed that cognitive development occurs in four periods or stages, and these stages have distinct beginnings and endings (Infographic 8.3).

Sensorimotor Stage

From birth to about 2 years old is the sensorimotor stage. Infants use their sensory abilities and motor activities (such as reaching, crawling, and handling things) to learn about the surrounding world, exploring objects with their mouths, fingers, and toes. It’s a nerve-racking process for parents (“Please do not put that shoe in your mouth!”), but an important part of cognitive development.

One significant milestone of the sensorimotor stage is object permanence, or an infant’s realization that objects and people still exist when they are out of sight or touch. Have you ever watched a young infant play peekaboo? Her surprise when your face appears from behind your hands indicates that to a certain extent she forgot you were there when your face was hidden. Jasmine tried to play peekaboo with Eddie when he was a baby, but he had a mixed reaction to the game, crying when she hid her face behind a blanket and laughing as soon as she pulled it away. Eddie’s fear of his mother’s disappearance and surprise at her reappearance didn’t last; he learned about object permanence.

Preoperational Stage

The next stage in cognitive development is the preoperational stage, which applies to children from 2 to 7 years old. During this time, children start using language to explore and understand their worlds (rather than relying primarily on sensory and motor activities). In this stage, children ask questions and use symbolic thinking. They may, for example, use words and images to refer to concepts. This is a time for pretending and magical thinking. Eddie, who is in this stage right now, likes to pretend he is Harry Potter. He drives Jasmine and Jocelyn crazy, racing around the house with a wand. Children in this phase are somewhat limited by their egocentrism. They can only imagine the world around them from their own perspective, and they have a hard time putting themselves in someone else’s shoes (see the Three Mountains task in Infographic 8.3). “Eddie is going through that ‘world stops when I say so’ phase right now,” Jasmine explains. He expects everyone around him to stop and listen to what he is saying. If he gets the attention he desires, all is well; if not, a screaming fit may ensue. According to Piaget (1936/1952), children in this stage have not yet mastered operations (hence, it is called the preoperational stage), which are the logical reasoning processes that older children and adults use to understand the world. For example, these children have a difficult time understanding the reversibility of some actions or events. They may have trouble comprehending that vanilla ice cream can be refrozen after it melts, but not turned back into sugar, milk, and vanilla.

The fact that children in this stage have not yet mastered operations is also apparent in their errors concerning the concept of conservation, which refers to the unchanging properties of volume, mass, or amount in relation to appearance (Figure 8.4). For example, if you take two masses of clay of the same shape and size, and then roll only one of them out into a hotdog shape, a child at this age will think that the longer-shaped clay is now made up of more clay than the undisturbed clump of clay. Even though she watched you take the clump of clay and roll it, without adding anything, she sees that the clump is longer and assumes it is made up of more clay. Or, the child may look at the newly formed clump of clay and see that it is skinnier, and therefore assume it is smaller. Why is this so? Children at this age generally focus on only one characteristic of an object. They do not understand the logical reasoning behind conservation or how the object stays fundamentally the same, even if it is manipulated or takes on a different appearance.

Concrete Operational Stage

Around age 7, children enter what Piaget called the concrete operational stage. They begin to think more logically, but mainly in reference to concrete objects and circumstances: things that can be seen or touched, or are well defined by strict rules. Children in this stage tend to be less egocentric and can understand the concept of conservation. However, their logical thinking is limited to concrete concepts; thus, they still have trouble with abstract concepts. Around age 8 or 9, Jocelyn tended to take everything literally. Once she asked to go outside when it was pouring rain, and Jasmine replied, “Are you crazy? It’s raining cats and dogs!” Jocelyn became distressed and cried, “The poor little kitties are gonna get hurt when they fall from the sky!” Children in this stage also have trouble thinking hypothetically. A 7-year-old may respond with a blank stare if you ask her a “what if?” type of question. (If you were able to travel to the future, what kind of animals would your great grandchildren see in the wild?)

INFOGRAPHIC 8.3: Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Jean Piaget proposed that children’s cognitive development occurs in stages characterized by particular cognitive abilities. These stages have distinct beginnings and endings.

Formal Operational Stage

At age 11, children enter the formal operational stage; they begin to think more logically and more systematically than younger children. They can solve problems such as those in the Third Eye task in Infographic 8.3. This activity asks a child where she would put a third eye, and why. (I’d put it in the back of my head so that I could see what is going on behind my back.) These types of capabilities do not necessarily develop overnight, and logical abilities are likely to advance in relation to interests and skills developed in a work setting. Piaget suggested that not everyone reaches this stage of formal operations. But to succeed in most colleges, this type of logical thinking is essential; students need to think critically and use abstract concepts to solve problems.

The Critics

Critics of Piaget suggest that although cognitive development might occur in stages with distinct characteristics, the transitions from one stage to the next are likely to be gradual, and do not necessarily represent a complete leap from one type of thinking to the next. Some believe Piaget’s theory underestimates children’s cognitive abilities. For example, some researchers have found that object permanence occurs sooner than suggested by Piaget (Baillargeon, Spelke, & Wasserman, 1985). Others have questioned Piaget’s assertion that the formal operational stage is reached by 11 to 12 years of age, and that no further delineations can be made between the cognitive abilities of adolescents and adults of various ages. One solution is to consider stages beyond Piaget’s original formulation, that is, to account for cognitive changes occurring in adulthood.

Vygotsky and Cognitive Development

LO 11 List the key elements of Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development.

One other major criticism of Piaget’s work is that it does not take into consideration the social interactions that influence the developing child. Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (vī-ˈgät-skē; 1896–1934) was particularly interested in how social and cultural factors affect a child’s cognitive development (Vygotsky, 1934/1962).

What are some of the social factors that influence cognitive development? Children are like apprentices in relation to others who are more capable and experienced (Zaretskii, 2009). Those children who receive help from older children and adults progress more quickly in their cognitive abilities. For example, when parents help their children solve puzzles by providing support for them to succeed on their own, the children show advancement in goal-directed behavior and the ability to plan ahead (Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, 2010; Hammond, Müller, Carpendale, Bibok, & Liebermann-Finestone, 2012).

One way we can support children’s cognitive development is through scaffolding: pushing them to go just beyond what they are competent and comfortable doing, but also providing help in a decreasing manner. We should offer guidance and examples to a greater degree at the beginning of the learning process, but give less help as the child becomes more skilled in a particular arena. A parent or caregiver provides support when necessary, but allows a child to solve problems independently: “Successful scaffolding is like a wave, rising to offer help when needed and receding as the child regains control of the task” (Hammond et al., 2012, p. 275).

Vygotsky also emphasized that learning always occurs within the context of a child’s culture. Children across the world have different sets of expected learning outcomes, from raising sheep to weaving blankets to playing basketball. We need to keep these cross-cultural differences in mind when exploring cognitive development in children.

SOME THINGS NEVER CHANGE

Jocelyn and Eddie have very different personalities, and their unique characteristics began to surface early in their development. Jocelyn has always been easygoing and mild-mannered. As an infant, she would cry and fuss as infants do, but her discontent could usually be traced to a clear cause (for example, she was hungry or tired). Eddie was more apt to cry for no obvious reason; he was more difficult to please; and Jasmine describes him as having had a “hot” temper.

Jocelyn and Eddie have very different personalities, and their unique characteristics began to surface early in their development. Jocelyn has always been easygoing and mild-mannered. As an infant, she would cry and fuss as infants do, but her discontent could usually be traced to a clear cause (for example, she was hungry or tired). Eddie was more apt to cry for no obvious reason; he was more difficult to please; and Jasmine describes him as having had a “hot” temper.

Jocelyn was a social butterfly from the start. As an infant, she would perk up on hearing a voice or spotting a person’s face, and she began to talk at an early age. Baby Eddie was not such a “people person.” He was more entranced by the bright colors and shapes he saw on TV programs for infants and toddlers. He also began to talk and walk considerably later than Jocelyn. But as his pediatrician said, these developmental discrepancies probably had a lot to do with gender (boys tend to lag behind girls in language and motor skills) and the fact that Eddie was born 2½ months early.

Many of Jocelyn’s and Eddie’s personality traits remained stable through toddlerhood. Both children started day care around the age of 2, but their adjustments to this change in routine were starkly different. Jocelyn, always very social, never cried after being dropped off. Eddie, the more introverted sibling, cried every day for 3 or 4 months. Why he had such a hard time saying goodbye is unclear, but there are probably many reasons. Perhaps he preferred the quiet solitude of home to the bustling environment of the childcare center, or maybe it had something to do with the fact that his parents were separating at the time. Eddie was experiencing separation anxiety, and we usually see this peak at approximately 13 months (Hertenstein & McCullough, 2005). Eddie has now been in day care or school for 3 years and has no problem being away from home. Any delays in language or motor development he experienced as a result of prematurity have long since vanished. “Now,” says Jasmine, “he is 5 going on 15, mentally and physically.”

Temperament and Attachment

Until now, we have mostly discussed physical and cognitive development, but recall we are also interested in socioemotional development. When thinking about Jocelyn and Eddie, it is important to consider their relationships, emotional processes, and personality characteristics.

Temperament

From birth, infants display characteristic differences in their behavioral patterns and emotional reactions, that is, their temperament. Some babies and toddlers can be categorized as having an exuberant temperament, showing an overall positive attitude and sociability (Degnan et al., 2011). “High-reactive” infants exhibit a great deal of distress when exposed to unfamiliar stimuli, such as new sights, sounds, and smells. “Low-reactive” infants do not respond to new stimuli with great distress (Kagan, 2003). Classification as high- and low-reactive is based on measures of behavior, emotional response, and physiology (such as heart rate and blood pressure; Kagan, 1985, 2003).

These different characteristics seem to be innate, as they are evident from birth and consistent in the infants’ daily lives. There is also evidence that some of these characteristics remain fairly stable throughout life (Kagan & Snidman, 1991). However, the environment can influence temperament (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). Factors such as maternal education, neighborhood, and paternal occupation through adolescence can predict characteristics of adult temperament (such as persistence, shyness, and impulsiveness; Congdon et al., 2012).

Easy, Difficult, or Slow to Warm Up

Researchers have shown that the majority of infants can be classified as having one of three fundamental temperaments (Thomas & Chess, 1986). Around 40% are considered “easy” babies; they are easy to care for because they follow regular eating and sleeping schedules. These happy babies can be soothed when upset and don’t appear to get rattled by transitions or changes in their environments. Jasmine would put Jocelyn in this category. Baby Jocelyn’s crying and fussiness were usually for obvious reasons (she was exhausted or thirsty), and she settled down when the problem was resolved.

“Difficult” babies (around 10%) are more challenging because they don’t seem to have a set schedule for eating and sleeping. And they don’t deal well with transitions or changes in the environment. Difficult babies are often irritable and unhappy, and compared to easy babies, they are far less responsive to the soothing attempts of caregivers. They also tend to be very active, kicking their legs on the changing table and wiggling like mad when you try to put on their clothes.

“Slow to warm up” babies (around 15%) are not as irritable (or active) as difficult babies, but they are not fond of change. Give them enough time, however, and they will adapt. Jasmine would place Eddie in this category. Eddie was not too keen on the new day care environment, but he did eventually adjust to it. He was just slow to warm up to the unfamiliar place and the people there.

These categories of baby temperaments are useful, but we should remember that 35% of babies are considered hard to classify because they share the characteristics of more than one type of temperament.

nature AND nurture

Destiny of the Difficult Baby

Perhaps you are wondering about the long-term implications of baby temperaments. What becomes of infants—particularly the difficult bunch—when they get older? Do they grow up to be difficult children, stirring up trouble in school and alienating other kids with their grumpy behavior? If the answer were unequivocally yes, then we would chalk it up to nature: Difficult is written into the genes and no amount of excellent parenting is going to change such babies. Fortunately, this does not appear to be the case. Research suggests that difficult babies are unusually sensitive to input from their parents, a characteristic that—depending on environmental circumstances—can be either a blessing or a curse (Stright, Gallagher, & Kelley, 2008).

Perhaps you are wondering about the long-term implications of baby temperaments. What becomes of infants—particularly the difficult bunch—when they get older? Do they grow up to be difficult children, stirring up trouble in school and alienating other kids with their grumpy behavior? If the answer were unequivocally yes, then we would chalk it up to nature: Difficult is written into the genes and no amount of excellent parenting is going to change such babies. Fortunately, this does not appear to be the case. Research suggests that difficult babies are unusually sensitive to input from their parents, a characteristic that—depending on environmental circumstances—can be either a blessing or a curse (Stright, Gallagher, & Kelley, 2008).

Stright and colleagues (2008) studied over a thousand mothers and babies during the first 6 years of life. Baby temperament was assessed at 6 months, and the mothers and their children were observed interacting on six separate occasions, from 6 months old until the time they were first graders. The children’s first-grade teachers also participated, filling out questionnaires about their pupils’ academic and social skills.

DO DIFFICULT BABIES BECOME OBNOXIOUS CHILDREN?

The researchers found that children with mothers demonstrating “higher-quality parenting styles” (being emotionally responsive and respectful of their children’s need for independence) fared better than those with moms exhibiting lower-quality parenting (emotional distance and disregard for autonomy). Come first grade, children exposed to higher-quality parenting were more likely to succeed academically and maintain positive relationships with peers and teachers. Meanwhile, first graders raised by more detached and controlling mothers had the most trouble adjusting to school. The effects—both good and bad—were magnified for the difficult babies, suggesting these children are more receptive to parenting in general (Stright et al., 2008). Nature may have endowed them with a “difficult” temperament, but with some encouragement and respect from loving parents, their energy could be channeled in a very constructive way.

As you can see, parents have the power to steer the development of their children in positive and negative directions. But what exactly makes a good parent? The adjectives or phrases that come to our minds are “patience,” “sensitivity,” “acceptance,” “strength,” and “unconditional love.” It also helps to be soft, warm, and snuggly—especially if you happen to be a monkey.

The Harlows and Their Monkeys

As we have noted, infants need contact with caregivers. Among the first to explore this topic in an experimental situation were Harry Harlow, Margaret Harlow, and their colleagues at the University of Wisconsin (Harlow, Harlow, & Suomi, 1971). The researchers were initially interested in learning how physical contact affects the development of loving relationships between infants and mothers. But they realized this would be difficult to study with human infants; instead, they turned to studying newborn macaque monkeys (Harlow, 1958).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed research ethics and the importance of ensuring the ethical treatment of research participants (human and animal). Psychologists must do no harm and safeguard the welfare of participants. This would not have been possible if the Harlows had taken human newborns from their parents to study the importance of physical contact. Many even question the ethics of their use of newborn monkeys in this manner.

Infant monkeys were put in cages alone, each with two artificial “surrogate” mothers. One surrogate was outfitted with a soft cloth and heated with a bulb. The other surrogate mother was designed to be lacking in “contact comfort,” as she was made of wire mesh and not covered in cloth. Both of these surrogates could be set up to feed the infants. In one study, half the infant monkeys received their milk from the cloth surrogates and the other half got their milk from the wire surrogates. The great majority of the infant monkeys spent most of their time clinging to or in contact with the cloth mother, even if she was not the mother providing the milk. The baby monkeys spent 15 to 18 hours a day physically close to the cloth mother, and only 1 to 2 hours touching the wire mother.

Harlow and colleagues also created situations in which they purposefully scared the infants with a moving toy bear, and found that the great majority of the infant monkeys (around 80%) ran to the cloth mother, regardless of whether she was a source of milk. In times of fear and uncertainty, these infant monkeys found more comfort in the soft and furry mothers. Through their experiments, Harlow and his colleagues showed how important physical contact was for these living creatures (Harlow, 1958; Harlow & Zimmerman, 1959).

Attachment

Physical contact plays an important role in attachment, or the degree to which an infant feels an emotional connection with primary caregivers. Using a design called the Strange Situation, Mary Ainsworth (1913–1999) studied the attachment styles of infants between 12 and 18 months (Ainsworth, 1979, 1985; Ainsworth & Bell, 1970; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). The Strange Situation goes roughly like this: A mother and child are led into a room. A stranger enters, and the mother then exits the room, leaving the child in the unfamiliar environment with the stranger, who tries to interact with the child. The mother returns to the room but leaves again, and then returns once more. At this point, the stranger departs. During the observation, the researchers note the amount of anxiety displayed by the child before and after the stranger arrives, the child’s willingness to explore the unfamiliar environment, and the child’s response to the mother’s return. The following response patterns were observed:

- Secure attachment: Around 65% of the children were upset when their mothers left the room, but were easily soothed upon her return, quickly returning to play. These children seemed confident that their needs would be met and felt safe exploring their environment, using the caregiver as a “secure base.”

- Avoidant attachment: Approximately 20% of the children displayed no distress when their mothers left, and they did not show any signs of wanting to interact with their mothers when they returned, seemingly happy to play in the room without looking at their mothers or the stranger. They didn’t seem to mind when their mothers left, or fuss when they returned.

- Ambivalent: Children in this group (around 10%) were quite upset and very focused on their mothers, showing signs of wanting to be held, but unable to be soothed by their mothers. These children were angry (often pushing away their mothers) and not interested in returning to play.

Ideally, parents or caregivers provide a secure base for infants, and are ready to help regulate emotions (soothe or calm) or meet other needs. This makes infants feel comfortable exploring their environments. Ainsworth and colleagues (1978) suggested that development, both physical and psychological, is greatly influenced by the quality of an infant’s attachment to caregivers. But, much of the early research in this area focused on infants’ attachment to their mothers. Subsequent research suggests that we should examine infants’ attachment to multiple individuals (mother, father, caregivers at day care, and close relatives), as well as cross-cultural differences in attachment (Field, 1996; Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2000).

Critics of the Strange Situation method suggest it creates an artificial environment and does not provide good measures of how infant–mother pairs act in their natural environments. Some suggest that the temperament of infants predisposes them to react the way they do in this setting. Infants prone to anxiety and uncertainty are more likely to respond negatively to such a scenario (Kagan, 1985). More generally, attachment theories are criticized for not considering cross-cultural differences in relationships (Rothbaum et al., 2000).

Attachments are formed early in childhood, but they have implications for a lifetime: “Experiences in early close relationships create internal working models that then influence cognition, affect, and behavior in relationships that involve later attachment figures” (Simpson & Rholes, 2010, p. 174). People who experienced ambivalent attachment as infants tend to have strong desires for continued closeness in adult relationships. Those who had secure attachments are more likely to expect that they are lovable and that others are capable of love. They are aware that nobody is perfect, and this attitude allows for intimacy in relationships (Cassidy, 2001). Infant attachment may even have long-term health consequences. One 32-year longitudinal study found that adults who had been insecurely attached as infants were more likely to report inflammation-based illnesses (for example, asthma, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes) than those with secure attachments (Puig, Englund, Simpson, & Collins, 2013).

Eerikson’s Psychosocial Stages

LO 12 Identify how Erikson’s theory explains psychosocial development through puberty.

One useful way to understand socioemotional development is to consider its progression through stages. According to Erik Erikson (1902–1994), human development is marked by eight psychosocial stages, spanning infancy to old age (Erikson & Erikson, 1997). Each of these stages is marked by a developmental task or an emotional crisis that must be handled successfully to allow for healthy psychological growth. The crises, according to Erikson, stem from conflicts between the needs of the individual and the expectations of society (Erikson, 1993). Successful resolution of a stage enables an individual to approach the following stage with more tools. Unsuccessful resolution leads to more difficulties during the next stage. Let’s take a look at the stages associated with infancy and childhood (TABLE 8.2).

| Stage | Age | Positive Resolution | Negative Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trust versus mistrust | Birth to 1 year | Trusts others, has faith in others. | Mistrusts others, expects the worst of people. |

| Autonomy versus shame and doubt | 1 to 3 years | Learns to be autonomous and independent. | Learns to feel shame and doubt when freedom to explore is restricted. |

| Initiative versus guilt | 3 to 6 years | Becomes more responsible, shows the ability to follow through. | Develops guilt and anxiety when unable to handle responsibilities. |

| Industry versus inferiority | 6 years to puberty | Feels a sense of accomplishment and increased self-esteem. | Feels inferiority or incompetence, which can later lead to unstable work habits. |

| Ego identity versus role confusion | Puberty to twenties | Tries out roles and emerges with a strong sense of values, beliefs, and goals. | Lacks a solid identity, experiences withdrawal, isolation, or continued role confusion. |

| Intimacy versus isolation | Young adulthood (twenties to forties) | Creates meaningful, deep relationships. | Lives in isolation. |

| Generativity versus stagnation | Middle adulthood (forties to mid-sixties) | Makes a positive impact on the next generation through parenting, community involvement, or work that is valuable and significant. | Experiences boredom, conceit, and selfishness. |

| Integrity versus despair | Late adulthood (mid-sixties and older) | Feels a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. | Feels regret and dissatisfaction. |

| These are the eight stages of psychosocial development proposed by Erik Erikson. Each stage is marked by a developmental task or an emotional crisis that must be handled successfully to allow for healthy psychological growth. | |||

| SOURCE: ERIKSON AND ERIKSON (1997). | |||

- Trust versus mistrust (birth to 1 year): In order for an infant to learn to trust, her caregivers must be responsive and attentive to her needs. If caregivers are not responsive, she will develop in the direction of mistrust, always expecting the worst of people and her environment.

- Autonomy versus shame and doubt (1 to 3 years): If his caregivers allow it, a child will learn how to be autonomous and independent. If a child in this stage is not given the freedom to explore, but is punished or restricted, he will likely learn to feel shame and doubt.

- Initiative versus guilt (3 to 6 years): In this age range, children have more experiences that prompt them to extend themselves socially. Often they become more responsible and show the ability to make and follow through on plans. If a child does not have responsibilities or cannot handle them, she will develop feelings of guilt and anxiety.

- Industry versus inferiority (6 years to puberty): Children in this age range are generally engaged in a variety of learning tasks. When they are successful at these tasks, they begin to feel a sense of accomplishment and their self-esteem increases. If a child at this stage does not succeed at tasks, he will feel a sense of inferiority or incompetence, and theoretically this lack of industriousness in childhood could lead to unstable work habits or unemployment later on.

This introduction to development during childhood provides an opportunity to understand the physical, cognitive, and socioemotional changes from birth to late childhood. But enough about children. The time has come to explore the exciting period of adolescence.

show what you know

Question 8.8

1. The ________ reflex occurs when you stroke a baby’s cheek; she opens her mouth and turns her head toward your hand. The ________ reflex occurs when you touch the baby’s lips; this reflex helps with feeding.

rooting; sucking

Question 8.9

2. Your instructor describes how he is teaching his infant to learn new words by showing her flashcards with images. Every time the infant uses the right word to identify the image, he gives her a big smile. When she uses an incorrect word, he frowns. Your instructor is using which of the following to guide his approach:

- theories of behaviorism.

- Chomsky’s language acquisition device.

- infant-directed speech.

- telegraphic speech.

a. theories of behaviorism

Question 8.10

3. Piaget suggested that when we try to understand new information and experiences by incorporating our already existing knowledge and ideas, we are using:

- the rooting reflex.

- schemas.

- accommodation.

- assimilation.

d. assimilation.

Question 8.11

4. Vygotsky recommended supporting children’s cognitive development by pushing them a little harder than normal, while providing help in a decreasing manner through ________.

scaffolding

Question 8.12

5. Erikson proposed that socioemotional development comprises eight psychosocial stages, and these stages include:

- scaffolding.

- physical maturation.

- developmental tasks or emotional crises.

- conservation.

c. developmental tasks or emotional crises.

Question 8.13

6. What advice would you give new parents about what to expect regarding the sequence of their child’s development of language and how they might help encourage it?

There is a universal sequence of language development. At around 2–3 months, infants typically start to produce vowel-like sounds known as cooing. At 4–6 months, in the babbling stage, infants combine consonants with vowels. This progresses to the one-word stage around 12 months, followed by two-word telegraphic speech at approximately 18 months. As children mature, they start to use more complete sentences. Infants pay more attention to adults who use infant-directed speech and are more likely to provide them with chances to learn and interact, thus allowing more exposure to language. Parents and caregivers should talk with their infants and children as much as possible, as babies benefit from a lot of chatter.