Theoretical Approaches to Gender Development

Researchers variously point to the influences of biological, cognitive-motivational, and cultural factors on gender development. First, biological differences between females and males—including the influence of sex hormones and brain structure differences—may partly account for average gender differences in some behaviors. Second, cognition and motivation—learning gender-typed roles through observation and practice—can shape children’s gender development. As highlighted in cognitive-motivational explanations, boys and girls are systematically provided different role models, opportunities, and incentives for gender-typed behavior by parents, teachers, peers, and the media. Finally, cultural factors, including the relative status of women and men in society, may shape children’s gender development.

As you will see in this section, there is empirical evidence for the role of each type of influence in certain behaviors. Indeed, it is likely that most aspects of gender development result from the complex interaction of all three sets of factors.

596

Biological Influences

Some researchers interested in biological influences on development consider possible ways that gender differences in behavior may have emerged during the course of human evolution. Other biologically oriented researchers focus more directly on identifying hormonal factors and differences in brain functioning as possible influences on gender differences in behavioral development.

Evolutionary Approaches

As discussed in Chapter 9, evolutionary theory proposes that certain characteristics that facilitate survival and the transmission of genes to succeeding generations have been favored over the course of human evolution. Developmental psychologists generally agree that evolution is important for understanding children’s development. However, there are different views regarding the proposal that females and males evolved different behavioral dispositions. Two examples are evolutionary psychology theory and biosocial theory.

Evolutionary psychology theory According to evolutionary psychology theory, certain behavioral tendencies occur because they helped humans survive during the course of evolution. Some evolutionary psychology theorists propose that particular gender differences in behavior reflect evolved personality dispositions. These theorists argue that sex-linked dispositions evolved to increase the chances that women and men would successfully mate and protect their offspring (Bjorklund & Pellegrini, 2002; D. M. Buss, 1999; Geary, 1998; Kenrick, Trost, & Sundie, 2004).

As noted in Chapter 9, studies of children’s play behavior show average gender differences that have been interpreted as consistent with the evolutionary perspective. For example, more boys than girls tend to engage in physically active, rough-and-tumble, and competitive types of play. Many boys devote considerable effort to jockeying with their male peers for dominance in groups. Geary (1999) proposed that boys’ play-fighting may represent an “evolved tendency to practice the competencies that were associated with male–male competition during human evolution” (p. 31). A propensity to engage in physical aggression is thought to have provided reproductive advantages for males in competition with other males for resources, including access to females (Geary, 1999, 2004).

In contrast, girls devote much effort to establishing and maintaining positive social relations, spend time in smaller groups of close female friends, and tend to avoid open conflict in their interactions. Girls also engage in much more play-parenting, including play with dolls, than boys do. From the evolutionary psychology perspective, these behaviors reflect evolved dispositions because maternal care in the form of breast-feeding was required for infants’ survival. In addition, nurturance and other affiliative behaviors may have increased the probability that their offspring would survive long enough to reproduce.

Evolutionary psychology theory is a popular approach, but a number of its proposals regarding gender differences are controversial. Some biologists and psychologists argue that many of evolutionary psychology theory’s claims about sex differences in personality traits cannot be tested (S. J. Gould, 1997; Lickliter & Honeycutt, 2003; W. Wood & Eagly, 2002). These critics also argue that some of the theory’s explanations are based on circular reasoning: If an average sex difference in behavior occurs—such as women being more likely than men to express nurturance—it is seen as having helped humans survive during the course of evolution, and it is considered adaptive during evolution because the average gender difference exists today. Such an argument merely asserts its premise as its conclusion and therefore is a difficult argument to test! Perhaps the clearest way to establish evidence of evolutionary influences would be to link sex differences in particular behaviors to genetic variations on sex chromosomes. We review work in this area later in the chapter.

597

Keep in mind that evolutionary psychology theory is not synonymous with all evolutionary approaches. An alternative evolutionary view emphasizes human evolution as maximizing our capacity for behavioral flexibility as an adaptation to environmental variability (S. J. Gould, 1997; Lickliter & Honeycutt, 2003). This view also points out that, because of their focus on biological constraints in gender development, some versions of evolutionary psychology theory can be construed as a rationalization for the status quo in traditional gender roles (Angier, 1999; S. J. Gould, 1997). As reviewed next, biosocial theory is an evolutionary approach that places more emphasis on the potential for behavioral flexibility while also acknowledging the impact of evolution on sex differences in physical characteristics.

Biosocial theory Wood and Eagly (2002) have offered biosocial theory as an alternative evolutionary approach to understanding gender development. Biosocial theory focuses on the evolution of physical differences between the sexes and proposes that these differences have behavioral and social consequences. For much of human history, the most important physical differences have been (1) men’s greater average size, strength, and foot speed and (2) women’s childbearing and nursing capacities. Men’s physical abilities gave them an advantage in activities such as hunting and combat and, in turn, tended to confer status and social dominance in the society. In contrast, bearing and nursing children limited women’s mobility and involvement in many forms of economic subsistence such as hunting.

However, according to biosocial theory, biology does not necessarily determine destiny. Nowadays in technological societies, men’s strength and other physical qualities are not relevant for most means of subsistence. For example, strength is irrelevant to succeeding as a manager, a lawyer, a physician, or an engineer. All these high-status occupations are now performed by women as well as by men (although gender equality is not fully realized in any of these occupations). Also, reproductive control and day care provide women greater flexibility to maintain their involvement in the labor force. Thus, according to biosocial theory, both physical sex differences and social ecology shape the different gender roles assigned to men and women—as well as the socialization of boys and girls.

As we have seen, some claims associated with evolutionary psychology theory are criticized for emphasizing biological determinants of gender differences. However, evolutionary psychologists take issue with biosocial theory, asserting that the body and the mind evolved together and that biosocial theory addresses only the body’s impact on gender development (Archer & Lloyd, 2002; Luxen, 2007). In sum, evolutionary psychology theory and biosocial theory both acknowledge the importance of the physical differences between women and men. But evolutionary psychology theorists additionally argue for the impact of sex differences in evolved behavioral dispositions.

598

Neuroscience Approaches

androgens  class of steroid hormones that normally occur at higher levels in males than in females and that affect physical development and functioning from the prenatal period onward

class of steroid hormones that normally occur at higher levels in males than in females and that affect physical development and functioning from the prenatal period onward

Researchers who take a neuroscience approach focus on testing whether and how hormones and brain functioning relate to variations in gender development (Berenbaum, 1998; Hines, 2004). Some neuroscience researchers also frame their work in terms of an evolutionary psychology perspective (Geary, 1998, 2004).

Hormones and brain functioning In the study of gender development, much attention has been paid to the possible effects of androgens, a class of steroid hormones that includes testosterone (Box 15.1). As discussed in Chapter 2, during normal prenatal development, the presence of androgens leads to the formation of male genitalia in genetic males; in their absence, female genitalia are formed in genetic females.

organizing influences  potential result of certain sex-linked hormones affecting brain differentiation and organization during prenatal development or at puberty

potential result of certain sex-linked hormones affecting brain differentiation and organization during prenatal development or at puberty

Androgens can also have organizing or activating influences on the nervous system. Organizing influences occur when certain sex-linked hormones affect brain differentiation and organization during prenatal development or at puberty. For example, sex-related differences in prenatal androgens may influence the organization and functioning of the nervous system; in turn, this may be related to later average gender differences in certain play preferences (see Berenbaum, 1998). Activating influences occur when fluctuations in sex-linked hormone levels influence the contemporaneous activation of certain brain and behavioral responses (Collaer & Hines, 1995). For example, as discussed later, the body increases androgen production in response to perceived threats, with possible implications for gender differences in aggression.

activating influences  potential result of certain fluctuations in sex-linked hormone levels affecting the contemporaneous activation of the nervous system and corresponding behavioral responses

potential result of certain fluctuations in sex-linked hormone levels affecting the contemporaneous activation of the nervous system and corresponding behavioral responses

Brain structure and functioning Male and female brains show some small differences in physical structure (Hines, 2004). One such difference is in the corpus callosum (the connection between the brain’s two hemispheres), which tends to be larger and to include more dense nerve bundles in women than in men (Driesen & Raz, 1995). When engaged in cognitive tasks (e.g., deciding whether words rhyme or navigating a maze), the male brain tends to show activations in one hemisphere or the other, whereas the female brain tends to show activations in both hemispheres (B. A. Shaywitz et al., 1995). However, this particular difference does not appear to result in any advantage to cognitive performance (D. F. Halpern, 2012).

Box 15.1: a closer look

GENDER IDENTITY: MORE THAN SOCIALIZATION?

Most children’s gender identification is consistent with their observable genitalia and gender socialization. That is, children’s view of themselves as “a girl” or “a boy” is consistent with their genetic sex and the gender-role expectations others hold for them. However, in some rare cases, children believe that their gender is not the one that others take it to be. Studies of such cases suggest that, once established, the child’s initial gender identification is often impervious to parental attempts to socialize the child as a member of what the child perceives as the “wrong” gender.

The potential power of children’s preferences over gender socialization occurs when children identify with the other gender. Some boys indicate a preference to identify as a girl, and some girls express a preference to identify as a boy. These children usually favor cross-gender-typed play activities and clothing and dislike gender-typed activities (Zucker & Bradley, 1995). Such discrepant gender identity usually appears very early in development, mostly occurs in boys, and can be difficult to alter even with parental socialization efforts. These cases suggest that gender identification has a biological component. The biological perspective points to the prenatal impact of sex hormones on the developing fetal brain. Such biological influences seem to contribute to gender identity as well as to behavioral gender differences.

gender dysphoria disorder  psychiatric diagnosis included in the DSM-5 to refer to children who identify with the other gender and indicate cross-gender-typed interests

psychiatric diagnosis included in the DSM-5 to refer to children who identify with the other gender and indicate cross-gender-typed interests

There is currently a debate in psychology over whether children with discrepant gender identities should be classified as having a psychiatric disorder. In the DSM-5, the latest version of the American Psychiatric Association’s (2013) compendium, these children receive the diagnosis of gender dysphoria disorder (formerly “gender identity disorder”). Some clinicians contend that children with discrepant gender identity are distressed and require care (Zucker, 2006). Other psychologists argue that applying a disorder label to children with cross-gender-typed interests merely reflects societal pressures for gender-role conformity (Bartlett, Vasey, & Bukowski, 2000).

transgender  a person whose gender identity does not match the person’s genetic sex; includes individuals who identify either with the other sex, with both sexes, or with neither sex.

a person whose gender identity does not match the person’s genetic sex; includes individuals who identify either with the other sex, with both sexes, or with neither sex.

Along these lines, some people argue for a broader notion of gender that goes beyond thinking only of the two categories of “female” or “male.” This includes acceptance of transgender youth and adults, individuals whose gender identity does not match their genetic sex. Some transgendered individuals prefer to identify with the other gender, with both genders, or with neither gender.

Another group of individuals who seek to broaden the gender spectrum include those born with intersex conditions (Preves, 2003). Intersex conditions are due to recessive genes that cause, in rare instances, a person of one genetic sex to develop genital characteristics typical of the other genetic sex. (Intersex individuals may also consider themselves transgender.) Two such intersex conditions are congenital adrenal hyperplasia and androgen insensitivity syndrome.

congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)  condition during prenatal development in which the adrenal glands produce high levels of androgens; sometimes associated with masculinization of external genitalia in genetic females; and sometimes associated with higher rates of masculine-stereotyped play in genetic females

condition during prenatal development in which the adrenal glands produce high levels of androgens; sometimes associated with masculinization of external genitalia in genetic females; and sometimes associated with higher rates of masculine-stereotyped play in genetic females

High levels of androgens produced during the prenatal development of genetic females can lead to congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), a condition that involves the formation of male (or partly masculinized) genitalia. Researchers have studied girls with CAH to infer the possible influence of androgens on gender development. They have found that, compared with other girls, those with CAH are more likely to choose physically active forms of play, such as rough-and-tumble play, and to avoid sedentary forms of play, such as playing with dolls (Berenbaum & Hines, 1992; Nordenström et al., 2002). This evidence has been used to support the idea that prenatal androgens may partly contribute to boys’ and girls’ gender identities and to gender-typed play preferences. In addition, this kind of evidence is sometimes used to support evolutionary accounts of gender development (G. M. Alexander, 2003).

androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS)  condition during prenatal development in which androgen receptors malfunction in genetic males, impeding the formation of male external genitalia; in these cases, the child may be born with female external genitalia.

condition during prenatal development in which androgen receptors malfunction in genetic males, impeding the formation of male external genitalia; in these cases, the child may be born with female external genitalia.

In contrast, androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS), a rare syndrome in genetic males, causes androgen receptors to malfunction. In these cases, genetic males may be born with female external genitalia.

599

One limitation of research documenting sex differences in brain structure is that it is mostly based on brain-imaging studies performed on adults. Given the continual interaction of genes and experience during brain development, it is unclear to what extent any differences in the brain’s structure or functioning seen in adults are due to genetic or environmental influences. It is also unclear to what extent these small differences in brain structure determine any gender differences in ability and behavior (D. F. Halpern, 2012).

Cognitive and Motivational Influences

self-socialization  active process during development whereby children’s cognitions lead them to perceive the world and to act in accord with their expectations and beliefs

active process during development whereby children’s cognitions lead them to perceive the world and to act in accord with their expectations and beliefs

Cognitive theories of gender development emphasize the ways that children learn gender-typed attitudes and behaviors through observation, inference, and practice. According to these explanations, children form expectations about gender that guide their behavior. Cognitive theories stress children’s active self-socialization: individuals use their beliefs, expectations, and preferences to guide how they perceive the world and the actions that they choose. Self-socialization occurs in gender development when children seek to behave in accord with their gender identity as a girl or a boy. However, cognitive theories also emphasize the role of the environment—the different role models, opportunities, and incentives that girls and boys might experience. We next discuss four pertinent cognitive theories of gender development: cognitive developmental theory, gender schema theory, social identity theory, and social cognitive theory.

600

Cognitive Developmental Theory

Lawrence Kohlberg’s (1966) cognitive developmental theory of gender-role development reflects a Piagetian framework (reviewed in Chapter 4). Kohlberg proposed that children actively construct knowledge in the same way, in the Piagetian view, that they construct knowledge about the physical world.

gender identity  awareness of oneself as a boy or a girl

awareness of oneself as a boy or a girl

Kohlberg maintained that children’s understanding of gender involves a three-stage process that occurs between approximately 2 to 6 years of age. First, by around 30 months of age, young children acquire a gender identity: they categorize themselves either as a girl or a boy (Fagot & Leinbach, 1989). However, they do not yet realize that gender is permanent. For example, young children may believe that a girl could grow up to be a father (Slaby & Frey, 1975). The second stage, which begins at around 3 or 4 years of age, is gender stability: children come to realize that gender remains the same over time (“I’m a girl, and I’ll always be a girl”). However, they are still not clear that gender is independent of superficial appearance and think that a boy who has put on a dress and now looks like a girl has become a girl.

gender stability  awareness that gender remains the same over time

awareness that gender remains the same over time

The basic understanding of gender is completed in the third stage, around 6 years of age, when children achieve gender constancy, the understanding that gender is invariant across situations (“I’m a girl, and nothing I do will change that”). Kohlberg noted that this is the same age at which children begin to succeed on Piagetian conservation problems and argued that both achievements reflect the same stage of thinking. Kohlberg maintained that children’s understanding that gender remains constant even when superficial changes occur is similar to their understanding that the amount of a substance is conserved even when its appearance is altered (a ball of clay that has been mashed flat is still the same amount of clay; a girl who gets her hair cut short and starts wearing baseball shirts instead of dresses is still a girl). According to Kohlberg, once gender constancy is attained, children begin to seek out and attend to same-gender models to learn how to behave (“Since I’m a girl, I should like to do girl things, so I need to find out what those are”).

gender constancy  realization that gender is invariant despite superficial changes in a person’s appearance or behavior

realization that gender is invariant despite superficial changes in a person’s appearance or behavior

Subsequent research has supported the idea that children’s understanding of gender develops in the sequence Kohlberg hypothesized and that the attainment of gender constancy occurs at more or less the same age as success on conservation problems (e.g., D. E. Marcus & Overton, 1978; Munroe, Shimmin, & Munroe, 1984). Studies also indicate that acquiring gender constancy increases the likelihood of many gender-typed behaviors (C. L. Martin et al., 2002). Gender schema theory, reviewed next, also addresses ways that attaining a concept of gender can affect children’s gender development.

Gender Schema Theory

Martin and Halverson (1981) proposed gender schema theory as an alternative to Kohlberg’s explanation of children’s gender development (also see Bem, 1981). In contrast to Kohlberg’s view that gender-typed interests emerge after gender constancy is achieved, gender schema theory holds that the motivation to enact gender-typed behavior begins as soon as children can label other people’s and their own gender—in other words, when they are toddlers.

601

gender schemas  organized mental representations (concepts, beliefs, memories) about gender, including gender stereotypes

organized mental representations (concepts, beliefs, memories) about gender, including gender stereotypes

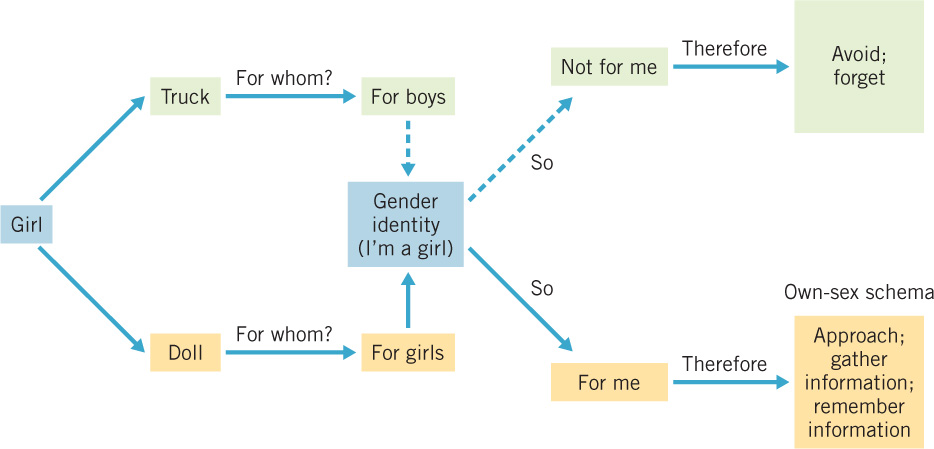

Accordingly, children’s understanding of gender develops through their construction of gender schemas, mental representations incorporating everything the child knows about gender. Gender schemas include memories of one’s own experiences with males and females, gender stereotypes transmitted directly by adults and peers (“boys don’t cry,” “girls play with dolls”), and messages conveyed indirectly through the media. Children use an ingroup/outgroup gender schema to classify other people as being either “the same as me” or not. The motivation for cognitive consistency leads them to prefer, pay attention to, and remember more about others of their own gender. As a consequence, an own-gender schema is formed, consisting of detailed knowledge about how to do things that are consistent with one’s own gender. Simply learning that an unfamiliar object is “for my gender” makes children like it more. Figure 15.1 illustrates how this process leads children to acquire greater knowledge and expertise with gender-consistent entities.

To test the impact of gender schemas on children’s information processing, 4- to 9-year-olds were given three boxes. Each contained unfamiliar, gender-neutral objects, and each was separately labeled as “boys,” “girls,” or “boys and girls/girls and boys.” The children spent more time exploring objects in boxes labeled for their own gender (or for both genders) than objects in the box labeled only for the other gender. One week later, not surprisingly, they remembered more details about the objects that they had explored than about the ones that they had spent less time with (Bradbard et al., 1986).

Children regularly look to their peers to infer gender-appropriate behavior. In an observational study conducted in a preschool classroom, boys were influenced by the number and the proportion of same-gender children who were playing with a set of toys: they approached toys that were being played with primarily by boys and shunned those that seemed popular mainly with girls (Shell & Eisenberg, 1990).

Gender schemas are also responsible for biased processing and remembering of information about gender. Consistent with the research described above, children tend to remember more about what they observe from same-gender than from cross-gender role models (Signorella, Bigler, & Liben, 1997; Stangor & McMillan, 1992). They are also more likely to accurately encode and remember information about story characters that behave in gender-consistent ways and to forget or distort information that is gender-inconsistent (Liben & Signorella, 1993; C. L. Martin & Halverson, 1983). For example, children who heard a story that featured a girl sawing wood often remembered it later as a story about a boy sawing wood. Similarly, children who saw pictures that showed a boy playing with a doll and a girl playing with a truck tended to misremember the gender of the children performing these respective actions (C. L. Martin & Halverson, 1983). This tendency to retain information that is schema-consistent and to ignore or distort schema-inconsistent information helps to perpetuate gender stereotypes that have little or no basis in reality.

602

gender schema filter  initial evaluation of information as relevant for one’s own gender

initial evaluation of information as relevant for one’s own gender

Liben and Bigler (2002) have added another component to gender schema theory. They proposed that children use two kinds of filters when processing information about the world. One is a gender schema filter (“Is this information relevant for my gender?”) and the other is an interest filter (“Is this information interesting?”). When encountering a new toy, for example, children may decide that it is something for girls or for boys and explore or ignore the toy on the basis of their gender schema filter. This is the same process emphasized in Martin and Halverson’s gender schema theory. However, Liben and Bigler noted that children sometimes find a new toy attractive without initially evaluating its appropriateness for their gender. In these instances, they use their interest filter to evaluate information. Furthermore, children sometimes use their interest filter to modify their gender schemas (“If I like this toy, it must be something that is okay for my gender”). Liben and Bigler’s modification to gender schema theory helps to account for findings indicating that children are often inconsistent in their gender-typed interests (for example, they are often more traditional in some areas than others). It also allows for the fact that some children actively pursue certain cross-gender-typed activities simply because they enjoy them.

interest filter  initial evaluation of information as being personally interesting

initial evaluation of information as being personally interesting

Although gender schemas are resistant to change, the contents of children’s gender schemas can be modified through explicit instruction. Such an approach was demonstrated by Bigler and Liben, who created a cognitive intervention program in which elementary school children learned that a person’s interests and abilities (but not gender) are important for the kind of job that the person could have (Bigler & Liben, 1990; Liben & Bigler, 1987). (The children were encouraged to see, for example, that if Mary was strong and liked to build things, a good job for her would be to work as a carpenter.) Children who participated in this week-long program showed decreased gender stereotyping and also had better memory for gender-inconsistent stimuli (such as a picture of a girl holding a hammer). However, a limitation of interventions aimed at reducing gender stereotyping is the fact that their impact typically fades once the intervention ends (Bigler, 1999). That is, children gradually revert back to their old gender stereotypes. Given the pervasiveness of gender stereotyping in children’s everyday lives, cognitive interventions need to be sustained to have a longer-lasting effect.

Social Identity Theory

ingroup bias  tendency to evaluate individuals and characteristics of the ingroup as superior to those of the outgroup

tendency to evaluate individuals and characteristics of the ingroup as superior to those of the outgroup

Developmental psychologists have highlighted the importance of gender as a social identity in children’s development (e.g., Bigler & Liben, 2007; J. R. Harris, 1995; Leaper, 2000; Nesdale, 2007; Powlishta, 1995). Indeed, gender may be the most central social identity in children’s lives (Bem, 1993). Children’s commitment to gender as a social identity is most readily apparent through their primary affiliation with same-gender peers (Leaper, 1994; Maccoby, 1998).

603

ingroup assimilation  process whereby individuals are socialized to conform to the group’s norms, demonstrating the characteristics that define the ingroup

process whereby individuals are socialized to conform to the group’s norms, demonstrating the characteristics that define the ingroup

Henri Tajfel and John Turner’s (1979) social identity theory addresses the influence of group membership on people’s self-concepts and behavior with others. Two influential processes that occur when a person commits to an ingroup are ingroup bias and ingroup assimilation. Ingroup bias refers to the tendency to evaluate individuals and characteristics associated with the ingroup as superior to those associated with the outgroup. For example, Kimberly Powlishta (1995) observed that children showed same-gender favoritism when rating peers on likeability and favorable traits. Ingroup bias is related to the process of ingroup assimilation, whereby individuals are socialized to conform to the group’s norms. That is, peers expect ingroup members to demonstrate the characteristics that define the ingroup. Thus, they anticipate ingroup approval for preferring same-gender peers and same-gender-typed activities, as well as for avoiding other-gender peers and cross-gender-typed activities (R. Banerjee & Lintern, 2000; C. L. Martin et al., 1999). As a result, children tend to become more gender-typed in their preferences as they assimilate into their same-gender peer groups (C. L. Martin & Fabes, 2001).

A corollary of social identity theory is that the characteristics associated with a high-status group are typically valued more than those of a low-status group. In male-dominated societies, masculine-stereotyped attributes such as assertiveness and competition tend to be valued more highly than feminine-stereotyped attributes such as affiliation and nurturance (Hofstede, 2000). Related to this pattern is the tendency of cross-gender-typed behavior to be more common among girls than among boys. Indeed, masculine-stereotyped behavior in a girl can sometimes enhance her status, whereas feminine-stereotyped behavior in a boy typically tarnishes his status (see Leaper, 1994).

Social identity theory helps to explain why gender-typing pressures tend to be more rigid for boys than for girls (Leaper, 2000). Members of high-status groups, for example, are usually more invested in maintaining group boundaries than are members of low-status groups. In most societies, males are accorded greater status and power than are females. Consistent with social identity theory, boys are more likely than girls to initiate and maintain role and group boundaries (Fagot, 1977; Sroufe et al., 1993). Boys are also more likely to endorse gender stereotypes (Rowley et al., 2007) and to hold sexist attitudes (C. S. Brown & Bigler, 2004).

Social Cognitive Theory

enactive experience  learning to take into account the reactions one’s past behavior has evoked in others

learning to take into account the reactions one’s past behavior has evoked in others

Kay Bussey and Albert Bandura (1999) proposed a theory of gender development based on Bandura’s (1986, 1997) social cognitive theory. The theory depicts a triadic model of reciprocal causation among personal factors, environmental factors, and behavior patterns. Personal factors include cognitive, motivational, and biological processes. Although the theory acknowledges the potential influence of biological factors, it primarily addresses cognition and motivation. Among its key features are sociocognitive modes of influence, observational learning processes, and self-regulatory processes.

tuition  learning through direct teaching

learning through direct teaching

observational learning  learning through watching other people and the consequences others experience as a result of their actions

learning through watching other people and the consequences others experience as a result of their actions

According to social cognitive theory, learning occurs through tuition, enactive experience, and observation. Tuition, which refers to direct teaching, occurs during gender socialization—for example, when a father shows his son how to throw a baseball, or a mother teaches her daughter how to change a baby’s diaper. Enactive experience occurs when children learn to guide their behavior by taking into account the reactions their past behavior has evoked in others. For instance, girls and boys usually get positive reactions for behaviors that are gender-stereotypical and negative reactions for behaviors that are counter-stereotypical (Fagot, 1977), and they tend to use this feedback to regulate their behavior in relevant situations. Finally, observational learning—the most common form of learning—occurs through seeing and encoding the consequences other people experience as a result of their actions. Thus, children learn a great deal about gender simply through observing the behavior of their parents, siblings, teachers, and peers. (Some examples of gender socialization in the family are described in Box 15.2.) Children also learn about gender roles through media such as television, films, and computer and video games (see Box 15.3).

604

Box 15.2: a closer look

GENDER TYPING AT HOME

Parents convey messages about gender in many ways. One is in the division of household labor. Although many American parents share responsibilities, most mothers and fathers in two-parent families tend to model traditional roles. Mothers are more likely to be primarily responsible for basic child-care and cleaning; fathers are more likely to be responsible for household maintenance. Analogous patterns tend to hold in parents’ assignment of household chores to daughters and sons. In general, boys are more likely than girls to take out the trash, help wash the car, mow the lawn, and perform other tasks outside the home. Girls are more likely than boys to help care for younger siblings and to perform other tasks inside the home (Grusec, Goodnow, & Cohen, 1996). This gender-based role modeling and assignment of chores implies a natural division of labor and may influence boys’ and girls’ emerging interests and preferences (Leaper, 2002).

gender-essentialist statements  remarks about males’ and females’ activities and characteristics phrased in language that implies they are inherent to the group as a whole

remarks about males’ and females’ activities and characteristics phrased in language that implies they are inherent to the group as a whole

In conversations between parents and children, parents often convey relatively subtle messages about gender through the use of gender-essentialist statements phrased in the timeless present tense, such as “Boys play football” and “Girls take ballet.” This linguistic form implies that the activities and implied characteristics in question are and always will be generally true of the group as a whole. In contrast, nonessentialist statements such as “Those girls are taking ballet lessons” carry no such implications. In a study of the comments that mothers made as they read stories to their toddlers or preschool children, nearly all (96%) used gender-essentialist language when referring to the gender of the story characters and activities (S. A. Gelman, Taylor, & Nguyen, 2004). They also used gender to distinguish the characters’ activities (“Does that look more like a boy job or a girl job?”). Such language use may convey the idea that gender is an important distinction and that gender-related characteristics are universal and stable (Leaper & Bigler, 2004).

Another difference in how parents talk to boys and to girls was found in a study that used naturalistic observation to document parent–child conversations in a science museum. While using interactive exhibits, parents were three times more likely to offer explanations to boys about what they were observing than they were to girls (Crowley et al., 2001). In a different study, researchers observed that when demonstrating a physics task to their school-aged children, fathers used more instructional talk (explanations, technical vocabulary) with sons than with daughters (Tenenbaum & Leaper, 2003). Presumably, both sets of findings occurred because adults assumed that boys are more scientifically inclined than are girls.

605

Box 15.3: applications

WHERE ARE SPONGESALLY SQUAREPANTS AND CURIOUS JANE?

Before reading further, take a moment to list your five favorite television programs. Now count the number of major characters in them who are female and male. Which characters are highly active and/or have positions of power on the show? How would you characterize the general nature of your programs—action-packed adventures, romantic comedies, sports shows, reality series? What would be different if you made a list of the programs you liked best as a child?

We would be willing to bet that your list of major characters includes more males than females, probably by a substantial degree. We also suspect that more male than female readers would list action and sports as favorite programs, whereas more female than male readers would have romantic shows on their lists. The imbalance in female and male characters in your current favorite shows is probably not much different from what you would find in the shows you watched in your youth.

The reason we feel such confidence in our predictions is that differences in the gender representation of characters on TV have been well documented, are very large, and have changed relatively little over the past three decades (Huston & Wright, 1998; Leaper et al., 2002; Signorielli, 2001; T. L. Thompson & Zerbinos, 1995). One study of children’s TV cartoons, however, did indicate that female and male characters were more equal in number and less gender-stereotyped in their portrayals on public television than on commercial television (Leaper et al., 2002).

The differential treatment of the sexes in the media is not limited to numbers. Portrayals of males and females tend to be highly stereotypical in terms of appearance, personal characteristics, occupations, and the nature of the characters’ roles. On average, male characters tend to be older and in more powerful roles; females tend to be young, attractive, and provocatively dressed (Diekman & Murnen, 2004; Gooden & Gooden, 2001; Leaper et al., 2002; Signorielli, 2012; T. L. Thompson & Zerbinos, 1995).

Do the large differences in both the number and nature of the portrayals of the sexes on TV matter? Keep in mind that for U.S. children, weekly TV consumption (including DVR, DVD, and the like) is over 32 hours for those between ages 2 and 5 and over 28 hours for those between ages 6 and 11 (The Nielsen Company, 2009). In addition, for most young children, television is a major source of information about the world at large (Gerbner et al., 2002). From a gender-typing perspective, the fact that children have so much exposure to highly stereotyped gender models matters a great deal. For example, children who watch a lot of TV have more highly stereotypic beliefs about males and females and prefer gender-typed activities to a greater extent than do children who are less avid viewers (Oppliger, 2007). Furthermore, several experimental studies have established a causal relationship between TV viewing and gender stereotyping (Oppliger, 2007). For example, when children are randomly assigned to watch TV shows with either gender-stereotyped or neutral content, they are more likely to endorse gender stereotypes themselves after watching gender-stereotyped programs.

Children are, of course, exposed to media other than television, but similar gender disparities have been documented in them as well. For example, children’s books still contain far more male than female characters, and characters of both sexes are often portrayed in gender-stereotypic ways. Males tend to be depicted as active and effective in the world at large, whereas females are frequently passive and prone to problems that require the help of males to solve (DeWitt, Cready, & Seward, 2013; Diekman & Murnen, 2004; Gooden & Gooden, 2001; Hamilton et al., 2006). Thus, although it is now possible to find more counter-stereotypical role models in children’s media (e.g., Hermione in the Harry Potter series), most female and male characters continue to be gender-stereotyped. Computer and online games are beginning to displace television as the primary source of children’s media entertainment. Unfortunately, like television programming, many computer games portray the sexes in highly stereotyped ways.

606

Observational learning of gender-role information involves four key processes: attention, memory, production, and motivation. To learn new information, it must, of course, be attended to (noticed) and then stored in memory. As we have noted, children often notice information that is consistent with their existing gender stereotypes. (This is the main premise of gender schema theory.) Next, children need to practice the behavior (production) that they have observed (assuming that the behavior is within their capabilities). Finally, children’s motivation to repeat a gender-typed behavior will depend on the incentives or disincentives they experience relative to the behavior. These sanctions can be experienced either directly (as when a parent praises a daughter for helping to prepare dinner) or indirectly (as when a boy observes another boy getting teased for playing with a doll). Over time, external sanctions are usually internalized as personal standards and become self-sanctions that motivate behavior.

According to the social cognitive theory, children monitor their behavior and evaluate how well it matches personal standards. After making this evaluation, children may feel pride or shame, depending on whether they meet their standards. When individuals experience positive self-reactions for their behavior, they gain the sense of personal agency referred to as self-efficacy. Self-efficacy can develop gradually through practice (as when a son regularly plays catch with his father), through social modeling (as when a girl observes a female friend do well in math and thinks that maybe she could do well herself), and by social persuasion (as when a coach gives a pep talk to push the boys’ performances on the baseball field). Researchers consistently find a strong relation between feelings of self-efficacy and motivation. For example, self-efficacy in math predicts girls’ as well as boys’ likelihood of taking advanced math courses (Stevens et al., 2007).

Cultural Influences

The theoretical approaches that we have discussed so far emphasize biological and cognitive-motivational processes involved in gender development. Complementing these approaches are theories that address the larger cultural and social-structural factors that can shape gender development. Two relevant theories that reflect this approach are the bioecological model and social role theory. Both emphasize how cultural practices mirror and perpetuate the gender divisions that are prevalent in a society.

Bioecological Model

opportunity structure  the economic and social resources offered by the macrosystem in the bioecological model, and people’s understanding of those resources

the economic and social resources offered by the macrosystem in the bioecological model, and people’s understanding of those resources

As described in Chapter 9, Urie Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model of human development differentiates among interconnected systems, from the microsystem (the immediate environment) to the macrosystem (the culture), that influence children’s development over time (see Figure 9.4) (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). A fundamental feature of the macrosystem is its opportunity structure, that is, the economic resources it offers and people’s understanding of those resources (Ogbu, 1981). Opportunities for members of a cultural community can vary depending on gender, income, and other factors and are reflected by the dominant adult roles within that cultural community.

According to the bioecological approach, child socialization practices in particular microsystems serve to prepare children for these adult roles. Thus, traditional gender-typing practices perpetuate as well as reflect the existing opportunity structures for women and men in a particular community at a particular time in history (Whiting & Edwards, 1988). To the extent that children’s development is largely an adaptation to their existing opportunities, changes in children’s macrosystems and microsystems can lead to greater gender equality (see Leaper, 2000). For example, increased academic and professional opportunities for girls in the United States have led to a dramatic narrowing of the gender gap in math and science within the past 30 years (D. F. Halpern et al., 2007).

607

Social Role Theory

A fundamental premise of Alice Eagly’s social role theory is that different expectations for each gender stem from the division of labor between men and women in a given society (Eagly, 1987; Eagly, Wood, & Diekman, 2000). To the extent that family and occupational roles are allocated on the basis of gender, different behaviors (roles) are expected of women and men (as well as of girls and boys). An obvious example, alluded to above, was the traditional exclusion of women from many occupations in the United States and similar societies. Women were underrepresented in politics, business, science, technology, and various other fields. In turn, girls were not expected to develop interests and skills that lead toward professions in those fields. Thus, somewhat similar to the bioecological model, social role theory highlights ways that institutionalized roles impose both opportunities and constraints on people’s behavior and beliefs in the home, schools, the labor force, and political institutions.

review:

To varying degrees, biological, cognitive-motivational, and cultural factors relate to different aspects of gender development. In their theories and work, researchers tend to focus on one set of factors—although they usually acknowledge that other influences are also important.

In trying to explain gender differences in behavior, some researchers focus on biological factors. Those who adopt an evolutionary perspective argue that gender differences in behavior emerged over the course of human evolution because they offered reproductive advantages to males and females. Disagreement exists, however, regarding the degree that evolution led to different behavioral predispositions for females and males. Other biological approaches focus on measureable physiological processes that may be related to variations in development, such as sex-related hormonal influences and sex differences in brain functioning.

Researchers who focus on cognitive-motivational processes emphasize how children’s gender-related beliefs, expectations, and preferences guide their behavior. Once children begin to identify with members of their own gender, they are typically motivated to acquire interests, values, and behavior in accord with their social identity as girls or boys. Self-socialization plays a prominent role in cognitive theories because it is primarily children themselves who initiate and enforce many forms of gender-typed behavior.

Cross-cultural comparisons and historical change within the United States and other countries underscore ways that gender roles are tied to culture. Societal values and cultural practices can limit or enhance the role models and opportunities that girls and boys experience during development.