Typical Speaking Assignments across the Curriculum

Before familiarizing yourself with the various course-specific types of oral presentations assigned in different disciplines consider the following kinds of presentation formats frequently assigned in various courses across the curriculum, including the review of an academic article, the debate, the poster presentation, and the service learning presentation. Some of these assignments may require an online component; for more information about speaking online, see Chapter 28.

The Review of Academic Articles

A commonly assigned speaking task in many courses is the review of academic articles. A biology instructor might ask you to review a study on cell regulation, for example, or a psychology teacher may require that you talk about a study on fetal alcohol syndrome. Typically, when you are assigned an academic article, your instructor will expect you to do the following:

- Identify the author’s thesis or hypothesis.

- Explain the methods by which the author arrived at his or her conclusions.

- Explain the author’s findings.

- Identify the author’s theoretical perspective, if applicable.

- Evaluate the study’s validity, if applicable.

- Describe the author’s sources and evaluate their credibility.

- Show how the findings of the study might be applied to other circumstances, and make suggestions about ways in which the study might lead to further research.1

The Team Presentation

Team presentations are oral presentations prepared and delivered by a group of three or more individuals. Regularly used in the classroom, successful team presentations require cooperation and planning. (See Chapter 29 for detailed guidelines on how to prepare and deliver team presentations.)

The Debate

Debates are a popular presentation format in many college courses, calling upon skills in persuasion (especially the reasoned use of evidence), in delivery, and in the ability to think quickly and critically. They allow participants to analyze arguments in depth and to challenge and defend positions. Good debaters are able to argue different points of view, including positions with which they disagree. Much like a political debate, in an academic debate two individuals or groups argue an issue from opposing viewpoints. Generally there will be a winner and a loser, lending this form of speaking a competitive edge.

Take a Side

Opposing sides in a debate are taken by speakers in one of two formats. In the individual debate format, one person takes a side against another person. In the team debate format, multiple people (usually two) take sides against another team, with each person on the team assuming a speaking role.

The affirmative side in the debate supports the topic with a resolution—a statement asking for change or consideration of a controversial issue. “Resolved, that the United States should provide amnesty to undocumented immigrants” is a resolution that the affirmative side must support and defend. The affirmative side tries to convince the audience (or judges) to address, support, or agree with the topic under consideration. The negative side in the debate attempts to defeat the resolution by dissuading the audience from accepting the affirmative side’s arguments.

Advance Strong Arguments

Whether you take the affirmative or negative side, your primary responsibility is to advance strong arguments in support of your position. Arguments usually consist (at the least) of the following three parts (see also Chapter 25):

- Claim: A claim makes an assertion or declaration about an issue—for example, “Undocumented immigrants should demonstrate that they can speak and understand English before gaining legal status.” Depending on your debate topic, your claim may be one of fact, value, or policy (see Chapter 25).

- Evidence: Evidence is the support offered for the claim—for example, that “Seventy-nine percent of Whites, 77 percent of Blacks, and 60 percent of Hispanics support an English language requirement, according to a June 2013 Pew Research Center survey on immigration.”

- Reasoning: Reasoning (e.g., warrants) is a logical link or explanation of why the evidence supports the claim. An example of reasoning or a warrant in support of the above claim and evidence would be “The majority of Americans want immigrants to learn English before they are granted citizenship so that the immigrants are better positioned to find employment and contribute to the economy.”

Debates are characterized by refutation, in which each side attacks the arguments of the other. Refutation can be made against an opponent’s claim, evidence, or reasoning, or some combination of these elements. An opponent might refute the other side’s evidence by arguing “The survey results used by my opponent are ten years old, and a new study indicates that opinion has changed by X percent.”

Refutation also involves rebuilding arguments that have been refuted or attacked by the opponent. This is done by adding new evidence or attacking the opponent’s reasoning or evidence.

“Flow” the Debate

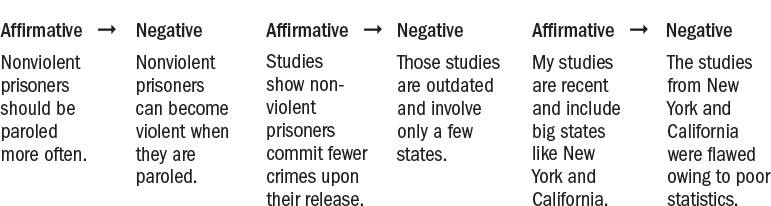

In formal debates (in which judges take notes and keep track of arguments), debaters must attack and defend each argument. “Dropping” or ignoring an argument can seriously compromise the credibility of the debater and her or his side. To ensure that you respond to each of your opponent’s arguments, try using a simple technique adopted by formal debaters called “flowing the debate” (see Figure 31.1). Write down each of your opponent’s arguments, and then draw a line or arrow to indicate that you (or another team member) have refuted it.

TIPS FOR WINNING A DEBATE

Present the most credible and convincing evidence you can find.

Present the most credible and convincing evidence you can find.

Before you begin, describe your position and tell the audience what they must decide.

Before you begin, describe your position and tell the audience what they must decide.

If you feel that your side is not popular among the audience, ask them to suspend their own personal opinion and judge the debate on the merits of the argument.

If you feel that your side is not popular among the audience, ask them to suspend their own personal opinion and judge the debate on the merits of the argument.

Don’t be timid. Ask the audience to specifically decide in your favor, and be explicit about your desire for their approval.

Don’t be timid. Ask the audience to specifically decide in your favor, and be explicit about your desire for their approval.

Emphasize the strong points from your arguments. Remind the audience that the opponent’s arguments were weak or irrelevant.

Emphasize the strong points from your arguments. Remind the audience that the opponent’s arguments were weak or irrelevant.

Be prepared to think on your feet (see Chapter 17 on impromptu speaking).

Be prepared to think on your feet (see Chapter 17 on impromptu speaking).

Don’t hide your passion for your position. Debate audiences appreciate enthusiasm and zeal.

Don’t hide your passion for your position. Debate audiences appreciate enthusiasm and zeal.

The Poster Presentation

A poster presentation includes information about a study, an issue, or a concept displayed concisely and visually on a large (usually roughly 4 × 6 foot) poster. Usually, poster presentations follow the structure of a scientific journal article, which includes an abstract, an introduction, a description of methods, a results section, a conclusion, and references. Presenters display their key findings on posters, arranged so session participants can examine them freely; on hand are copies of the written report, with full details of the study.

A good poster presenter considers his or her audience, understanding that with so much competing information, the poster must be concise, visually appealing, and focused on the most important points of the study. Different disciplines (e.g., geology versus sociology) require unique poster formats, so be sure that you follow the guidelines specific to the discipline.

When preparing the poster:

- Select a concise and informative title; make it 84-point type or larger.

- Include an abstract (a brief summary of the study) describing the essence of the report and how it relates to other research in the field. Offer compelling and “must know” points to hook viewers and summarize information for those who will only read the abstract.

- Ensure a logical and easy-to-follow flow from one part of the poster to another.

- Edit text to a minimum, using clear graphics wherever possible.

- Select a muted color for the poster itself—such as gray, beige, light blue, or white—and use a contrasting, clear font color (usually black).

- Make sure your font size is large enough to be read comfortably from at least 3 feet away.

- Design figures and diagrams to be viewed from a distance, and label each one.

- Include a concise summary of each figure in a legend below it.

- Be prepared to provide brief descriptions of your poster and to answer questions; keep your explanations short.2

The Service Learning Presentation

In a service learning presentation, students learn about and help address a need or problem in a community agency or nonprofit organization, such as may exist in a mental-health facility, an economic development agency, or an antipoverty organization. Typically, presentations about participation in a service learning project include the following information:

- Description of the service task.

- What organization, group, or agency did your project serve?

- What is the problem or issue and how did you address it?

- Description of what the service task taught you about those you served.

- How were they affected by the problem or issue?

- How did your solution help them? What differences did you observe?

- Explanation of how the service task and outcome related to your service learning course.

- What course concepts, principles, or theories related to your service project, and how?

- What observations gave you evidence that the principles applied to your project?

- Application of what was learned to future understanding and practice.

- How was your understanding of the course subject improved or expanded?

- How was your interest in or motivation for working in this capacity affected by the project?

- What do you most want to tell others about the experience and how it could affect them?