ORGANIZING YOUR SUPPORTING DETAILS

The body of your essay contains the paragraphs that support your thesis. Before you begin writing these paragraphs, decide on the supporting evidence you will use and the order in which you will present your evidence. (For more on developing a thesis and selecting evidence to support it, see Chapter 6).

SELECTING A METHOD OF ORGANIZATION

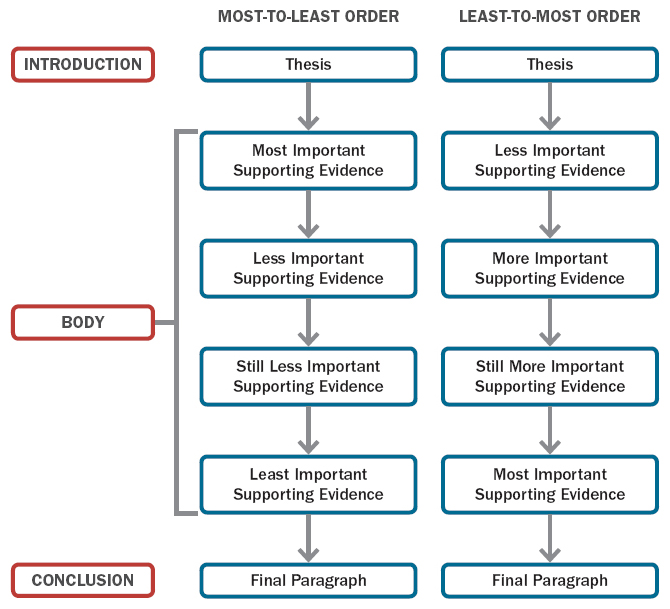

Three common ways to organize ideas are most-to-least (or least-to-most) order, chronological order, and spatial order. To decide which to use, consider your topic and how it can be most logically presented.

Most-to-least (or least-to-most) order When you choose this method of organizing an essay, you arrange your supporting details moving gradually from most to least (or least to most) important, familiar, or interesting. If you need to entice readers or expect they will read only the beginning of your essay, you might include your strongest evidence first. If readers are interested in the topic and likely to read on, you might hold your most memorable evidence for last. You can visualize these two options as follows:

A student, Robin Ferguson, devised this thesis statement: “Working as a literacy volunteer taught me more about learning and friendship than I ever expected.” She identified four primary benefits related to her thesis.

- I learned about the learning process.

- I developed a permanent friendship with my student, Marie.

- Marie built self-confidence.

- I discovered the importance of reading for Marie.

Ferguson then chose to arrange the supporting evidence from least to most important.

| LEAST | Paragraph 1: Learned about the learning process |

| TO MOST | Paragraph 2: Discovered the importance of reading for Marie |

| IMPORTANT | Paragraph 3: Marie increased her self-confidence |

| Paragraph 4: Developed a permanent friendship with Marie |

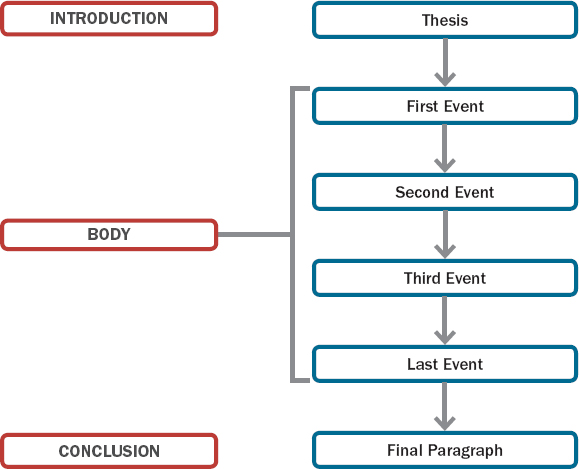

Chronological order When you arrange your supporting details in chronological (or time) order, you put them in the order in which they happened, beginning the body of your essay with the first event and progressing through the others as they occurred. Chronological order is commonly used in narrative essays (essays that tell a story or recount events) and process analyses (essays that explain how something works or is done). You can visualize chronological order as follows.

Suppose that Robin Ferguson, writing about her experiences as a literacy volunteer, decides to demonstrate her thesis by relating the events of a typical tutoring session. In this case, she might organize her essay by narrating the events in the order in which they usually occur, using each detail about the session to demonstrate what tutoring taught her about learning and friendship.

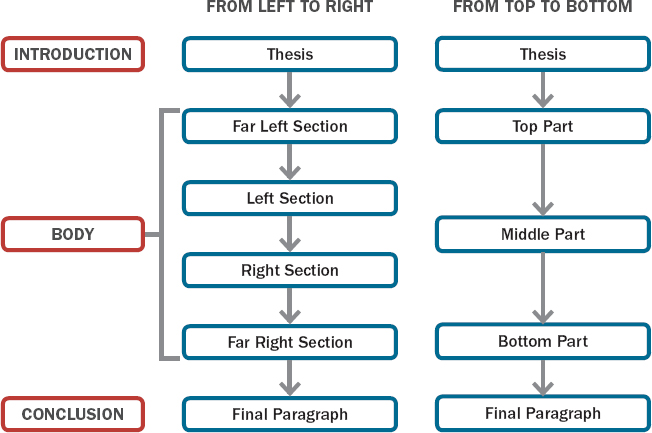

Spatial order When you use spatial order, you organize details about your subject by location. Spatial organization is commonly used in descriptive essays (essays that portray people, places, and things) as well as in classification and division essays (essays that explain categories or parts). Consider, for example, how you might use spatial order to support the thesis that movie theaters are designed to shut out the outside world and create a separate reality within. You could begin by describing the ticket booth, then the lobby, and finally the theater. Similarly, you might describe a person from head to toe. Robin Ferguson, writing about her experiences as a literacy volunteer, could describe her classroom or meeting area from front to back or left to right.

Visualize spatial organization by picturing your subject in your mind or by sketching it. “Look” at your subject systematically—from top to bottom, inside to outside, front to back. Cut it into imaginary sections or pieces and describe each piece. Here are two possible options for visualizing an essay that uses spatial order.

Essay in Progress 1

Choose one of the following activities.

- Using the thesis statement and evidence you gathered for the Essay in Progress activities in Chapter 6, choose a method for organizing your essay.

- Choose one of the following narrowed topics:

- Positive or negative experiences with computers

- Stricter (or more lenient) regulations for teenage drivers

- Factors that account for the popularity of action films

- Discipline in public elementary schools

- Advantages or disadvantages of instant messaging

Then, using the steps in Figure 7.1, prewrite to produce ideas, develop a thesis, and generate evidence to support the thesis. Next, choose a method for organizing your essay. Explain briefly how you will use that method of organization.

PREPARING AN OUTLINE OR A GRAPHIC ORGANIZER

After you have written a thesis statement and chosen a method of organization, take a few minutes to create an outline or graphic organizer of the essay’s main points in the order you plan to discuss them. This is especially important when your essay is long or complex. Outlining or drawing a graphic organizer can help you see how ideas fit together and may reveal places where you need to add supporting information.

Outlining There are two types of outlines: informal and formal. An informal (or scratch) outline uses key words and phrases to list main points and subpoints. Below is an informal outline of Robin Ferguson’s essay. Recall that Ferguson chose to use the least-to-most-important method of organization.

|

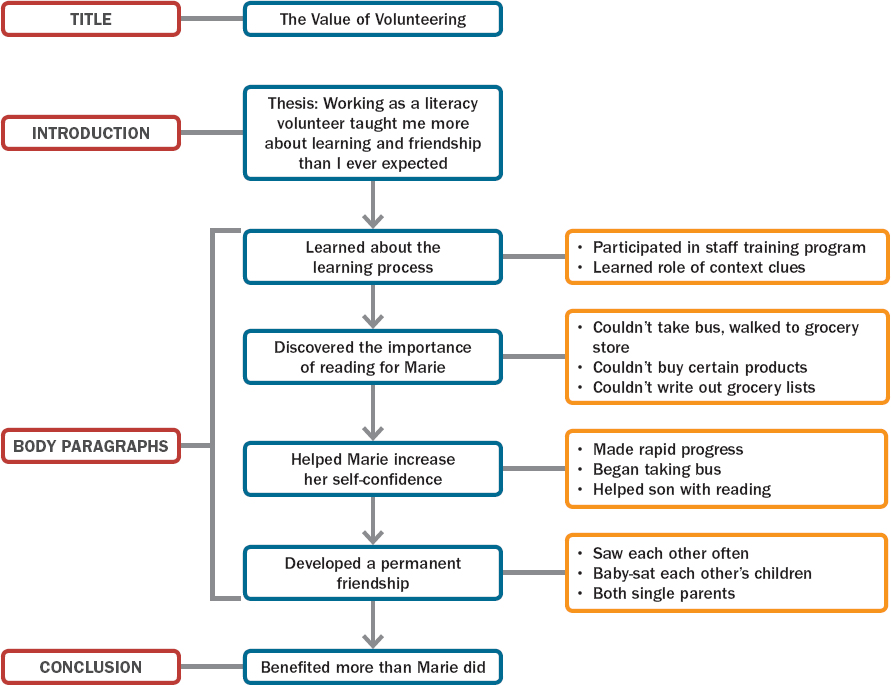

SAMPLE INFORMAL OUTLINE Thesis: Working as a literacy volunteer taught me more about learning and friendship than I ever expected. Paragraph 1: Learned about the learning process – Went through staff training program – Learned about words “in context” Paragraph 2: Discovered the importance of reading for Marie – Couldn’t take bus, walked to grocery store – Couldn’t buy certain products – Couldn’t write out grocery lists Paragraph 3: Marie increased her self-confidence – Made rapid progress – Began taking bus – Helped son with reading Paragraph 4: Developed a permanent friendship with Marie – Saw each other often – Both single parents – Baby-sat each other’s children Conclusion: I benefited more than Marie did. |

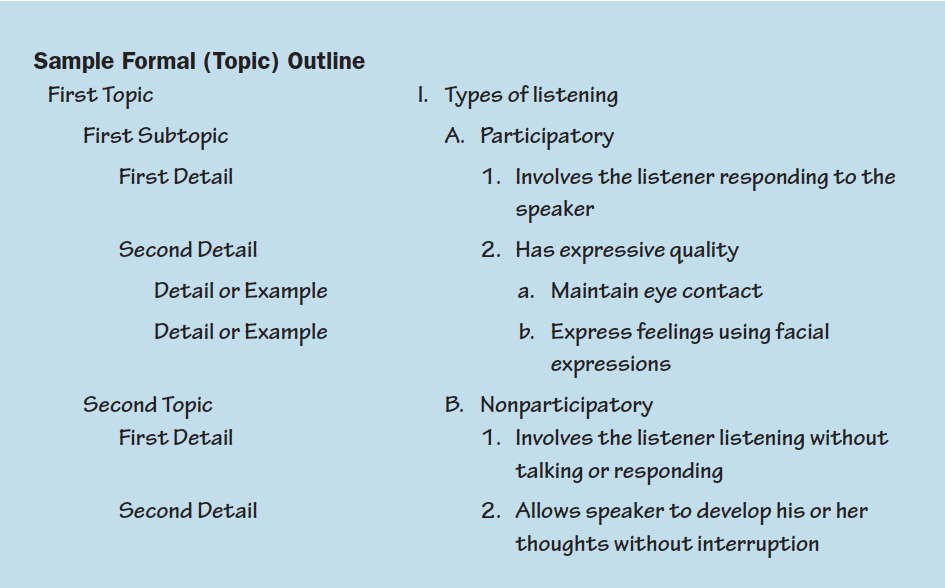

Formal outlines use Roman numerals (I, II), capital letters (A, B), Arabic numbers (1, 2), and lowercase letters (a, b) and indentation to designate levels of importance. Formal outlines fall into two categories.

- Sentence outlines use complete sentences.

- Topic outlines use only key words and phrases.

Here is a sample topic outline that a student wrote for an essay for her interpersonal communication class.

All items at the same level should be at the same level of importance, and each must explain or support the topic or subtopic under which it is placed. All items at the same level should also be grammatically parallel. (For more on parallel structure, see Chapter 10.)

| NOT PARALLEL |

|

| PARALLEL |

|

If your instructor allows, you can use both phrases and sentences within an outline, as long as you do so consistently. You might write all subtopics (designated by capital letters A, B, and so on) as sentences and all supporting details (designated by 1, 2, and so on) as phrases, for instance.

Learning Style Options

Preparing a graphic organizer If you have a pragmatic learning style, a verbal learning style, or both, preparing an outline will probably appeal to you. If you are a creative or spatial learner, however, you may prefer to draw a graphic organizer. Figure 7.3 shows the graphic organizer that Robin Ferguson created for her essay. Notice that it follows the least-to-most-important method of organization, as did her informal outline.

Whichever method you find more appealing, begin by putting your working thesis statement at the top of a page and listing your main points below. Leave plenty of space between main points. While you are filling in details that support one main point, you will often think of details or examples to use in support of a different one. As these details or examples occur to you, jot them down under or next to the appropriate main point on your outline or graphic organizer. (To learn more about creating a graphic organizer, see Chapter 3.)

Essay in Progress 2

For the topic you chose in Essay in Progress 1, prepare an outline or draw a graphic organizer to show your essay’s organizational plan.