Sentence-Level Issues

Printed Page 679-691

Sentence-Level Issues

|

BASIC CHARACTERISTICS OF A SENTENCE |

A sentence has five characteristics.

1. It starts with an uppercase letter and ends with a period, a question mark, or (rarely) an exclamation point attached to the final word.

I have a friend.

Do you have a friend?

I asked, “Do you have a friend?”

The question mark is part of the quoted question.

Did you write “Ode to My Friend”?

The question mark is part of the question, not part of the title in quotation marks.

Yes! You are my best friend!

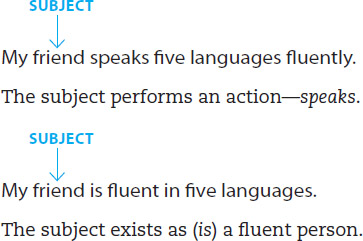

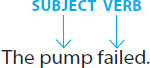

2. It has a subject, usually a noun. The subject performs the action(s) mentioned in the sentence or exists in a certain condition according to the rest of the sentence.

3. It has a verb, which tells what the subject does or states its existence.

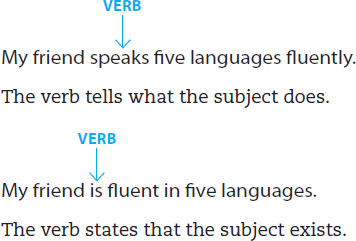

4. It has a standard word order.

The most common sequence in English is subject-verb-object:

You can add information in various places.

Yesterday we hired a consulting firm.

Information was added to the start of the sentence.

Yesterday we hired a consulting firm: Sanderson & Associates.

Information was added to the end of the sentence.

Yesterday we hired the city’s most prestigious consulting firm: Sanderson & Associates.

Information was added in the middle of the sentence.

In fact, any element of a sentence can be expanded.

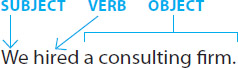

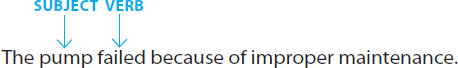

5. It has an independent clause (a subject and verb that can stand alone—that is, a clause that does not begin with a subordinating word or phrase).

The following is a sentence:

The following is also a sentence:

But the following is not a sentence because it lacks a subject with a verb and because it begins with a subordinating phrase:

Because of improper maintenance.

An independent clause is required to complete this sentence:

Because of improper maintenance, the pump failed.

One way to connect ideas in a sentence is by coordination. Coordination is used when the ideas in the sentence are roughly equal in importance. There are three main ways to coordinate ideas:

1. Use a semicolon (;) to coordinate ideas that are independent clauses.

The information for bid was published last week; the proposal is due in less than a month.

2. Use a comma and a coordinating conjunction (and, but, or, nor, so, for, or yet) to coordinate two independent clauses.

The information for bid was published last week, but the proposal is due in less than a month.

In this example, but clarifies the relationship between the two clauses: the writer hasn’t been given enough time to write the proposal.

3. Use transitional words and phrases to coordinate two independent clauses. You can end the first independent clause with a semicolon or a period. If you use a period, begin the transitional word or phrase with a capital letter.

The Intel 6 Series chipset has already been replaced; as a result, it is hard to find an Intel 6 Series in a new computer.

The Intel 6 Series chipset has already been replaced. As a result, it is hard to find an Intel 6 Series in a new computer.

Two ideas can also be linked by subordination—that is, by deemphasizing one of them. There are two basic methods of subordination:

1. Use a subordinating word or phrase to turn one idea into a subordinate clause.

| after | because | since | until | while |

| although | before | so that | when | who |

| as | even though | that | where | whom |

| as if | if | unless | which | whose |

Start with two independent clauses:

The bridge was completed last year. The bridge already needs repairs.

Then choose a subordinating word and combine the clauses:

Although the bridge was completed last year, it already needs repairs.

Although subordinates the first clause, leaving it already needs repairs as the independent clause.

Note that a writer could reverse the order of the ideas:

The bridge already needs repairs even though it was completed last year.

Another way to subordinate one idea is to turn it into a nonrestrictive clause using the subordinating word which:

The bridge, which was completed last year, already needs repairs.

This version deemphasizes was completed last year by turning it into a nonrestrictive clause and emphasizes already needs repairs by leaving it as the independent clause.

2. Turn one of the ideas into a phrase modifying the other.

Completed last year, the bridge already needs repairs.

Completed last year was turned into a phrase by dropping the subject and verb from the independent clause. Here the phrase is used to modify the bridge.

The four tenses used most often in English are simple, progressive, perfect, and perfect progressive.

1. SIMPLE: an action or state that was, is, or will be static or definite

SIMPLE PAST (VERB + ed [or irregular past])

Yesterday we subscribed to a new ecology journal.

The action of subscribing happened at a specific time. The action of subscribing definitively happened regardless of what happens today or tomorrow.

SIMPLE PRESENT (VERB or VERB + s)

We subscribe to three ecology journals every year.

The action of subscribing never changes; it’s regular, definite.

SIMPLE FUTURE (will + VERB or simple present of be + going to + VERB)

We will subscribe to the new ecology journal next year.

We are going to subscribe to the new ecology journal next year.

The action of subscribing next year (a specific time) will not change; it is definite.

2. PROGRESSIVE: an action in progress (continuing) at a known time

PAST PROGRESSIVE (simple past of be + VERB + ing)

We were updating our directory when the power failure occurred.

The action of updating was in progress at a known time in the past.

PRESENT PROGRESSIVE (simple present of be + VERB + ing)

We are updating our directory now.

The action of updating is in progress at a known time, this moment.

FUTURE PROGRESSIVE (simple future of be + VERB + ing)

We will be updating our directory tomorrow when you arrive.

The action of updating will be in progress at a known time in the future.

3. PERFECT: an action occurring (sometimes completed) at some indefinite time before a definite time

PAST PERFECT (simple past of have + VERB + ed [or irregular past])

We had already written the proposal when we got your call.

The action of writing began and ended at some indefinite past time before a definite past time.

PRESENT PERFECT (simple present of have + VERB + ed [or irregular past])

We have written the proposal and are proud to hand it to you.

The action of writing began at some indefinite past time and is being commented on in the present, a definite time.

FUTURE PERFECT (simple future of have + VERB + ed [or irregular past])

We will have written the proposal by the time you arrive.

The action of writing will have begun and ended at some indefinite time in the future before the definite time in the future when you arrive.

4. PERFECT PROGRESSIVE: an action in progress (continuing) until a known time

PAST PERFECT PROGRESSIVE (simple past of have + been + VERB + ing)

We had been working on the reorganization when the news of the merger became public.

The action of working continued until a known time in the past.

PRESENT PERFECT PROGRESSIVE (simple present of have + been + VERB + ing)

We have been working on the reorganization for over a year.

The action of working began at some indefinite past time and is continuing in the present, when it is being commented on.

FUTURE PERFECT PROGRESSIVE (simple future of have + been + VERB + ing)

We will have been working on the reorganization for over a year by the time you become CEO.

In the future, the action of working will have been continuing before another future action.

English uses the -ing form of verbs in three major ways:

1. As part of a progressive or perfect progressive verb (see numbers 2 and 4 in the “Verb Tenses” section)

We are shipping the materials by UPS.

We have been waiting for approval since January.

2. As a present participle, which functions as an adjective either by itself

the leaking pipe

or as part of a participial phrase

The sample containing the anomalies appears on Slide 14.

3. As a gerund, which functions as a noun either by itself

Writing is the best way to learn to write.

or as part of a gerund phrase

The designer tried inserting the graphics by hand.

Infinitives consist of the word to plus the base form of the verb (to write, to understand). An infinitive can be used in three main ways:

1. As a noun

The editor’s goal for the next year is to publish the journal on schedule.

2. As an adjective

The company requested the right to subcontract the project.

3. As an adverb

We established the schedule ahead of time to prevent the kind of mistake we made last time.

Instead of a one-word verb, many English sentences contain a verb phrase.

The system meets code.

This sentence has a one-word verb, meets.

The new system must meet all applicable codes.

This sentence has a two-word verb phrase, must meet.

The old system must have met all applicable codes.

This sentence has a three-word verb phrase, must have met.

In a verb phrase, the verb that carries the main meaning is called the main verb. The other words in the verb phrase are called helping verbs. The following discussion explains four categories of helping verbs.

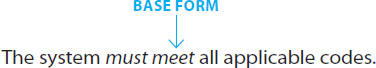

1. Modals

There are nine modal verbs: can, could, may, might, must, shall, should, will, and would. After a modal verb, use the base form of the verb (the form of the verb used after to in the infinitive).

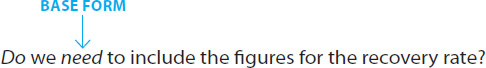

2. Forms of do

After a helping verb that is a form of do—do, does, or did—use the base form of the verb.

3. Forms of have plus the past participle

To form one of the perfect tenses (past, present, or future), use a form of have as the helping verb plus the past participle of the verb (usually the -ed form of the verb or the irregular past).

| PAST PERFECT | We had written the proposal before learning of the new RFP. |

| PRESENT PERFECT | We have written the proposal according to the instructions in the RFP. |

| FUTURE PERFECT | We will have written the proposal by the end of the week. |

4. Forms of be

To describe an action in progress, use a form of be (be, am, is, are, was, were, being, been) as the helping verb plus the present participle (the -ing form of the verb).

We are testing the new graphics tablet.

The company is considering flextime.

To create the passive voice, use a form of be plus the past participle.

The piping was installed by the plumbing contractor.

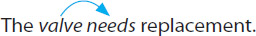

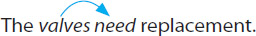

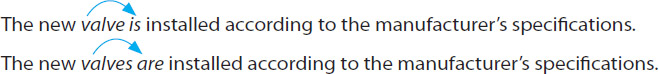

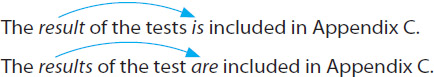

The subject and the verb in a clause or sentence must agree in number. That is, if the noun is singular, the verb must be singular.

Note the s that marks a singular present-tense verb.

If the noun is plural, the verb must be plural.

Note the s that marks a plural noun.

Here are additional examples of subject-verb agreement.

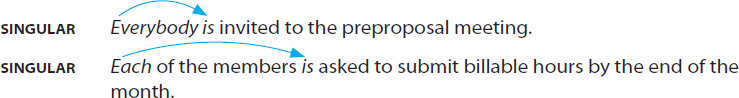

When you edit your document for subject-verb agreement, keep in mind the following guidelines:

1. When information comes between the subject and the verb, make sure the subject and verb agree.

2. Certain pronouns and quantifiers always require singular verbs. Pronouns that end in -one or -body—such as everyone, everybody, someone, somebody, anyone, anybody, no one, and nobody—are singular. In addition, quantifiers such as something, each, and every are singular.

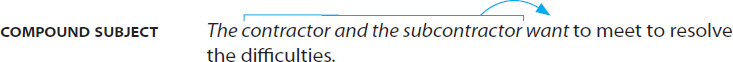

3. When the clause or sentence contains a compound subject, the verb must be plural.

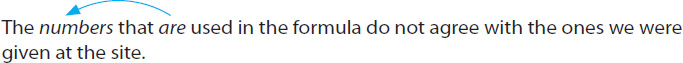

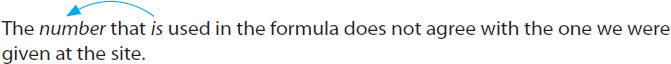

4. When a relative pronoun such as who, that, or which begins a clause, make sure the verb agrees in number with the noun that the relative pronoun refers to.

Numbers is plural, so the verb in the that clause (are) is also plural.

Number is singular, so the verb in the that clause (is) is also singular.

The word if in English can introduce four main types of conditions:

1. Conditions of fact

Conditions of fact usually—but not always—call for the same verb tense in both clauses. In most cases, use a form of the present tense:

If rats eat as much as they want, they become obese.

If you see “Unrecoverable Application Error,” the program has crashed.

Here the present perfect is needed, because the crashing is over when you see the message.

2. Future prediction

For prediction, use the present tense in the if clause. Use a modal (can, could, may, might, must, shall, should, will, or would) plus the base form of the verb in the independent clause.

If we win this contract, we will need to add three more engineers.

If this weather keeps up, we might postpone the launch.

3. Present-future speculation

The present-future speculation usage suggests a condition contrary to fact. Use were in the if clause if the verb is be; use the simple past in the if clause if it contains another verb. Use could, might, or would plus the base form of the verb in the independent clause.

If I were president of the company, I would be much more aggressive.

If I took charge of the company, I would be much more aggressive.

The example sentences imply that you are not president of the company and have not taken charge of it.

The past tense in the example if clauses shows distance from reality, not distance in time.

4. Past speculation

Use the past perfect in the if clause. Use could, might, or would plus the present perfect in the independent clause.

If we had won this contract, we would have needed to add three engineers.

This sentence implies that the condition is contrary to fact: the contract wasn’t won, so the engineers were not needed.

Few aspects of English can be as frustrating to the nonnative speaker as the correct usage of the articles a, an, and the before nouns. Although there are a few rules that you should try to learn, remember that there are many exceptions and special cases.

Here are some guidelines to help you look at nouns and decide whether they may or must take an article—or not. As you will see, to make the decision about an article, you must determine

- whether a noun is proper or common

- for a common noun, whether it is countable or uncountable

- for a countable common noun, whether it is specific or nonspecific, and if it is nonspecific, whether it is singular or plural

- for an uncountable common noun, whether it is specific or nonspecific

Specific in this context means that the writer and the reader can both identify the noun—“which one” it is.

1. Proper nouns

Singular proper nouns usually take no article but occasionally take a or an:

James Smith, but not John Smith, contributed to the fund last year. A Smith will contribute to the fund this year.

The speaker does not know which Smith will make the contribution, so an article is necessary. Assuming that there is only one person with the name Quitkin, the sentence “Quitkin will contribute to the fund this year” is clear, so the proper noun takes no article.

Plural proper nouns often, but not always, take the:

The Smiths have contributed for the past 10 years.

There are Smiths on the class roster again this year.

2. Countable common nouns

Singular and plural specific countable common nouns take the:

The microscope is brand new.

The microscopes are brand new.

Singular nonspecific countable common nouns take a or an:

A microscope will be available soon.

An electron is missing.

Plural nonspecific countable common nouns take no article but must have a plural ending:

Microscopes must be available for all students.

3. Uncountable common nouns

Specific uncountable common nouns take the:

The research started by Dr. Quitkin will continue.

The subject under discussion is specific research.

Nonspecific uncountable common nouns generally take no article:

Research is always critical.

The subject under discussion is nonspecific—that is, research in general.

Adjectives are modifiers. They modify—that is, describe—nouns and pronouns. Keep in mind four main points about adjectives in English:

1. Adjectives do not take a plural form.

a complex project

three complex projects

2. Adjectives can be placed either before the nouns they modify or after linking verbs.

The critical need is to reduce the drag coefficient.

The need to reduce the drag coefficient is critical.

3. Adjectives of one or two syllables usually take special endings to create the comparative and superlative forms.

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

| big | bigger | biggest |

| heavy | heavier | heaviest |

4. Adjectives of three or more syllables take the word more for the comparative form and the words the most for the superlative form.

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

| qualified | more qualified | the most qualified |

| feasible | more feasible | the most feasible |

Like adjectives, adverbs are modifiers. They modify—that is, describe—verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs. Their placement in a sentence is somewhat more complex than the placement of adjectives. Remember five points about adverbs:

1. Adverbs can modify verbs.

Management terminated the project reluctantly.

2. Adverbs can modify adjectives.

The executive summary was conspicuously absent.

3. Adverbs can modify other adverbs.

The project is going very well.

4. Adverbs that describe how an action takes place can appear in different locations in a sentence—at the beginning of a clause, at the end of a clause, right before a one-word verb, or between a helping verb and a main verb.

Carefully the inspector examined the welds.

The inspector examined the welds carefully.

The inspector carefully examined the welds.

The inspector was carefully examining the welds.

NOTE: The adverb should not be placed between the verb and the direct object.

INCORRECT The inspector examined carefully the welds.

5. Adverbs that describe the whole sentence can also appear in different locations in the sentence—at the beginning of the sentence, before an adjective, or at the end of the sentence.

Apparently, the inspection was successful.

The inspection was apparently successful.

The inspection was successful, apparently.

Except for imperative sentences, in which the subject you is understood (Get the correct figures), all sentences in English require a subject.

The company has a policy on conflict of interest.

Do not omit the expletive there or it.

| INCORRECT | Are four reasons for us to pursue this issue. |

| CORRECT | There are four reasons for us to pursue this issue. |

| INCORRECT | Is important that we seek his advice. |

| CORRECT | It is important that we seek his advice. |

1. Do not repeat the subject of a sentence.

| INCORRECT | The company we are buying from it does not permit us to change our order. |

| CORRECT | The company we are buying from does not permit us to change our order. |

2. In an adjective clause, do not repeat an object.

| INCORRECT | The technical communicator does not use the same software that we were writing in it. |

| CORRECT | The technical communicator does not use the same software that we were writing in. |

3. In an adjective clause, do not use a second adverb.

| INCORRECT | The lab where we did the testing there is an excellent facility. |

| CORRECT | The lab where we did the testing is an excellent facility. |

For more practice with the concepts covered in Part D, complete the LearningCurve activities under “Additional Resources” in Appendix, Part D: macmillanhighered.com/launchpad/techcomm11e.

For more practice with the concepts covered in Part D, complete the LearningCurve activities under “Additional Resources” in Appendix, Part D: macmillanhighered.com/launchpad/techcomm11e.