Writing Letters

Printed Page 363-371

Writing Letters

Letters are still a basic means of communication between organizations, with millions written each day. To write effective letters, you need to understand the elements of a letter, its format, and the common types of letters sent in the business world.

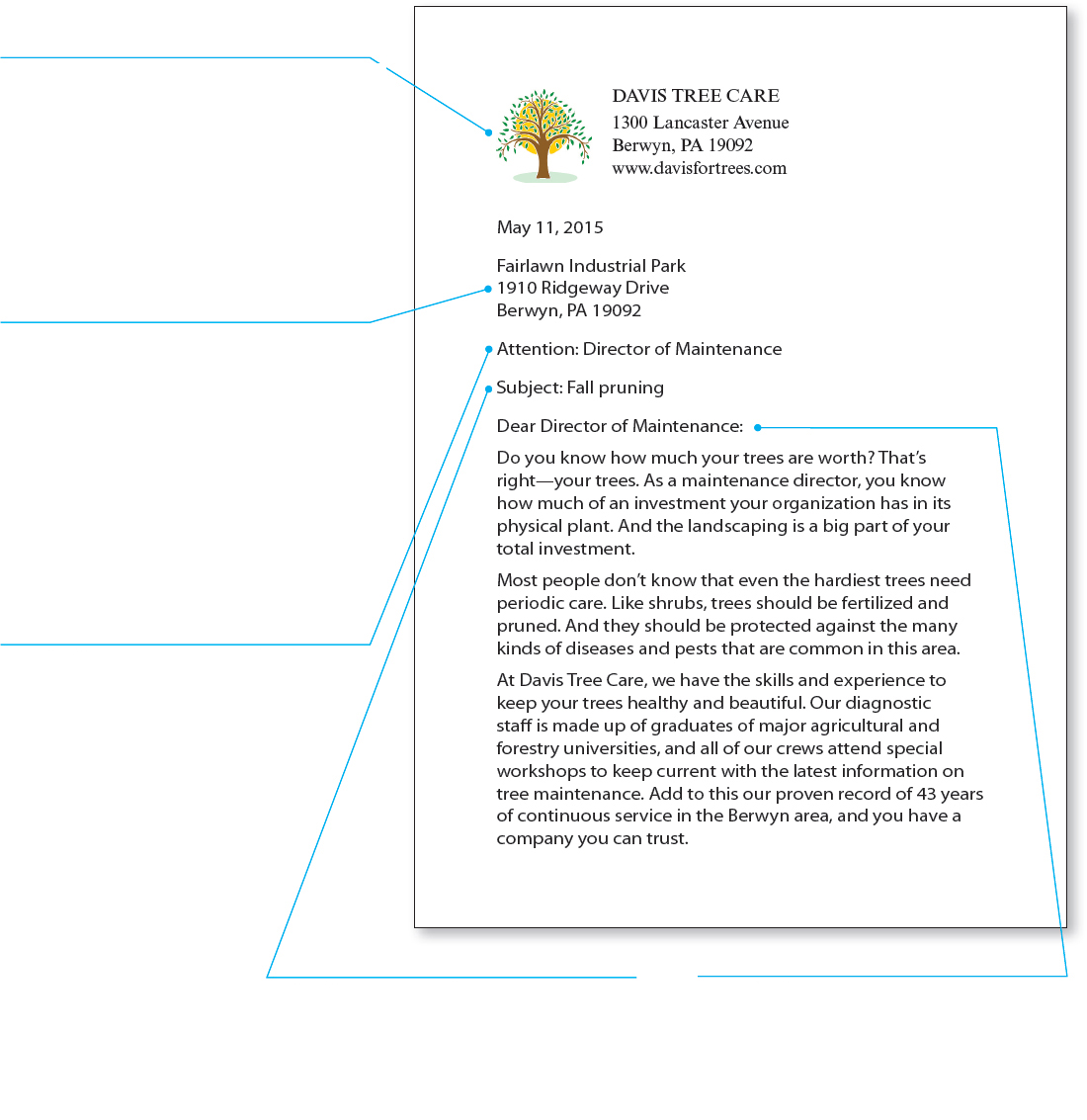

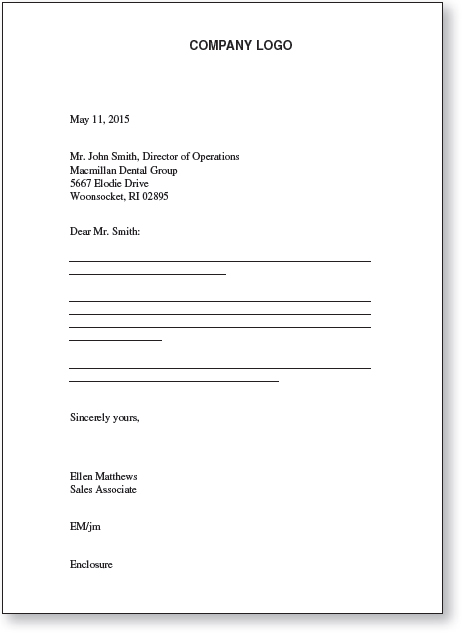

Most letters include a heading, inside address, salutation, body, complimentary close, and signature. Some letters also include one or more of the following: attention line, subject line, enclosure line, and copy line. Figure 14.3 shows the elements of a letter.

Heading. Most organizations use letterhead stationery with their heading printed at the top. This preprinted information and the date the letter is sent make up the heading. If you are using blank paper rather than letterhead, your address (without your name) and the date form the heading. Whether you use letterhead or blank paper for the first page, do not number it. Use blank paper for the second and all subsequent pages.

Inside Address. If you are writing to an individual who has a professional title—such as Professor, Dr., or, for public officials, Honorable—use it. If not, use Mr. or Ms. (unless you know the recipient prefers Mrs. or Miss). If the reader’s position fits on the same line as the name, add it after a comma; otherwise, drop it to the line below. Spell the name of the organization the way the organization itself does: for example, International Business Machines calls itself IBM. Include the complete mailing address: street number and name, city, state, and zip code.

Attention Line. Sometimes you will be unable to address a letter to a particular person because you don’t know (and cannot easily find out) the name of the individual who holds that position in the company.

Subject Line. The subject line is an optional element in a letter. Use either a project number (for example, “Subject: Project 31402”) or a brief phrase defining the subject (for example, “Subject: Price quotation for the R13 submersible pump”).

Salutation. If you decide not to use an attention line or a subject line, put the salutation, or greeting, two lines below the inside address. The traditional salutation is Dear, followed by the reader’s courtesy title and last name and then a colon (not a comma):

Dear Ms. Hawkins:

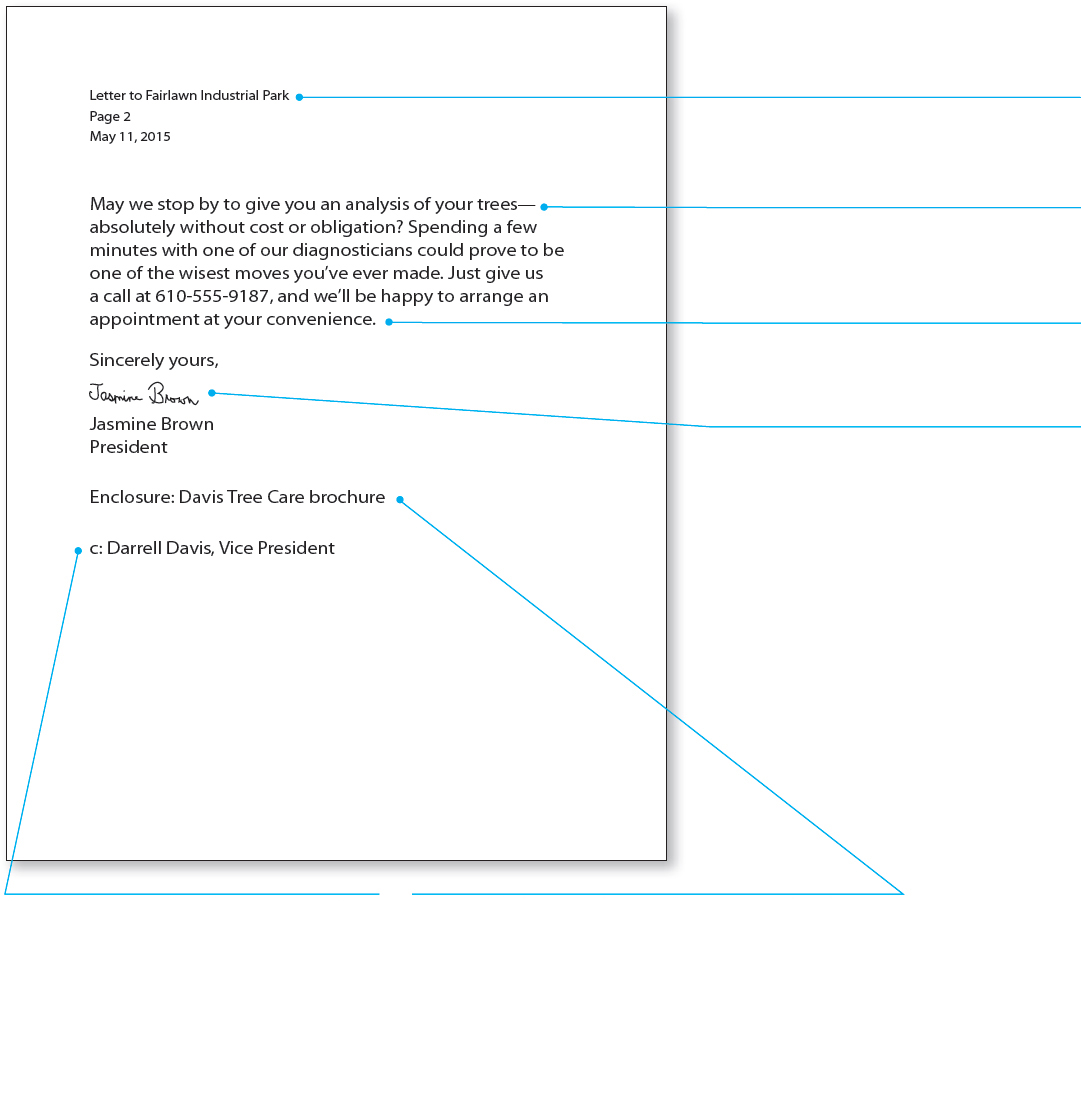

Header for second page.

Body. In most cases, the body contains at least three paragraphs: an introductory paragraph, a concluding paragraph, and one or more body paragraphs.

Complimentary Close. The conventional phrases Sincerely, Sincerely yours, Yours sincerely, Yours very truly, and Very truly yours are interchangeable.

Signature. Type your full name on the fourth line below the complimentary close. Sign the letter, in ink, above the printed name. Most organizations prefer that you include your position under your printed name.

Copy Line. If you want the primary recipient to know that other people are receiving a copy of the letter, include a copy line. Use the symbol c (for “copy”) followed by the names of the other recipients (listed either alphabetically or according to organizational rank). If appropriate, use the symbol cc (for “courtesy copy”) followed by the names of recipients who are less directly affected by the letter.

Enclosure Line. If the envelope contains documents other than the letter, include an enclosure line that indicates the number of enclosures. For more than one enclosure, add the number: “Enclosures (2).” In determining the number of enclosures, count only separate items, not pages. A three-page memo and a 10-page report constitute only two enclosures. Some writers like to identify the enclosures:

Enclosure: 2014 Placement Bulletin

Enclosures (2): “This Year at Ammex”

2014 Annual Report

Figure 14.4 Typical Letter Formats

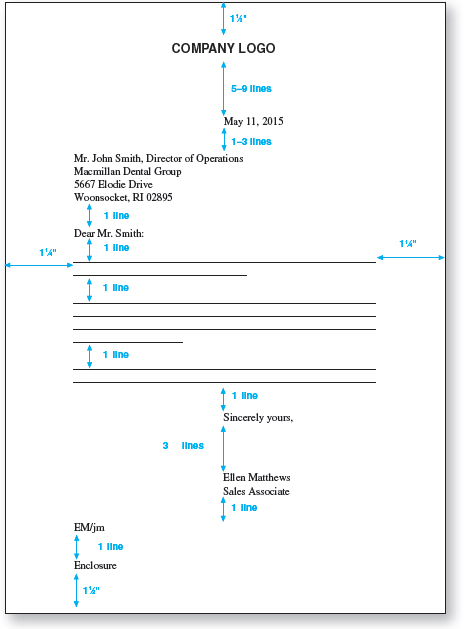

The dimensions and spacing shown for the modified block format also apply to the full block format.

Two other types of letters are discussed in this book: the transmittal letter in Ch. 18, and the job-application letter in Ch. 15.

Organizations send out many different kinds of letters. This section focuses on four types of letters written frequently in the workplace: inquiry, response to an inquiry, claim, and adjustment.

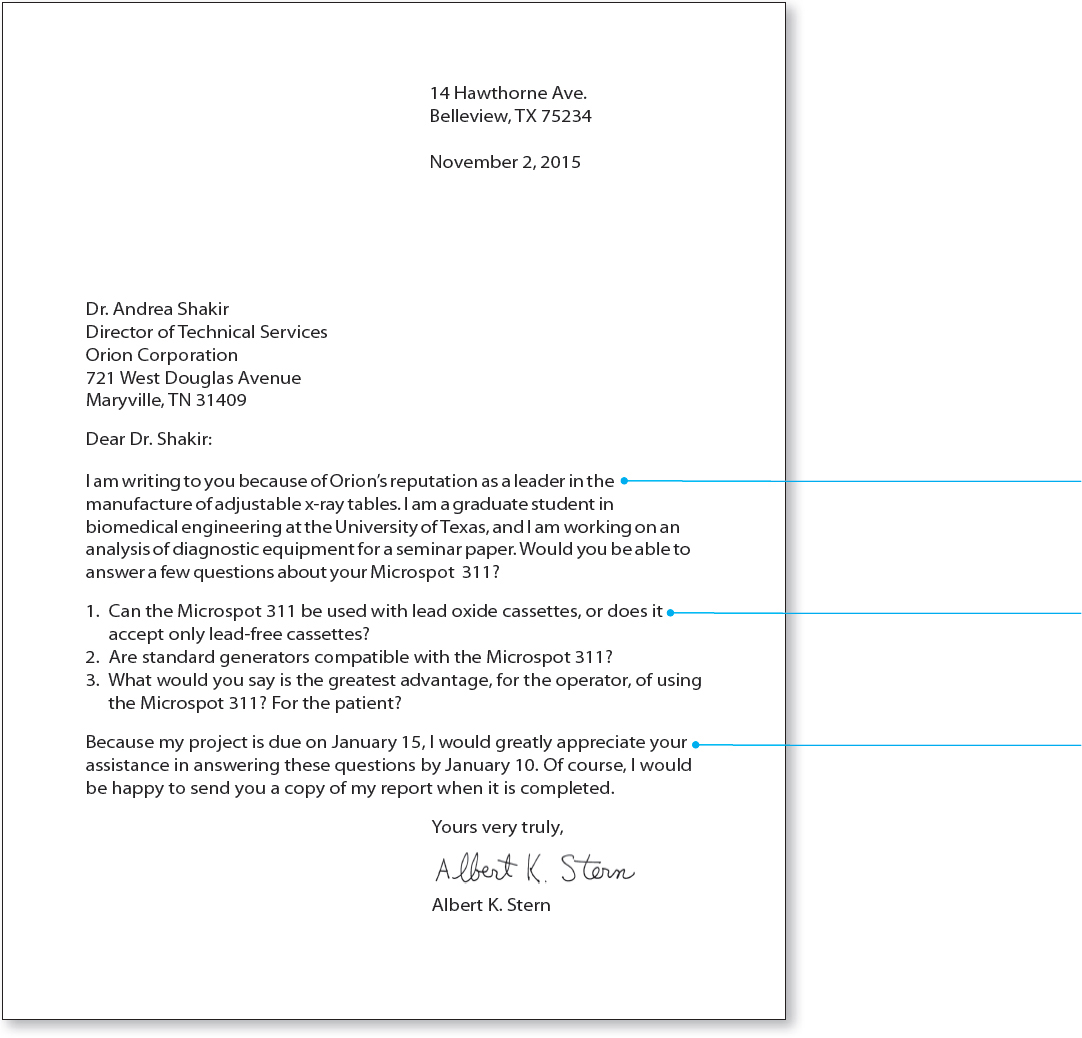

Inquiry Letter Figure 14.5 shows an inquiry letter, in which you ask questions.

Letters follow one of two typical formats: modified block or full block. Figure 14.4 illustrates these two formats.

Notice the flattery in the first sentence.

The writer presents specific questions in a list format, making the questions easy to read and understand.

In the final paragraph, the writer politely indicates his schedule and requests the reader’s response. Note that he offers to send the reader a copy of his report. If the reader provides information, the writer should send a thank-you letter.

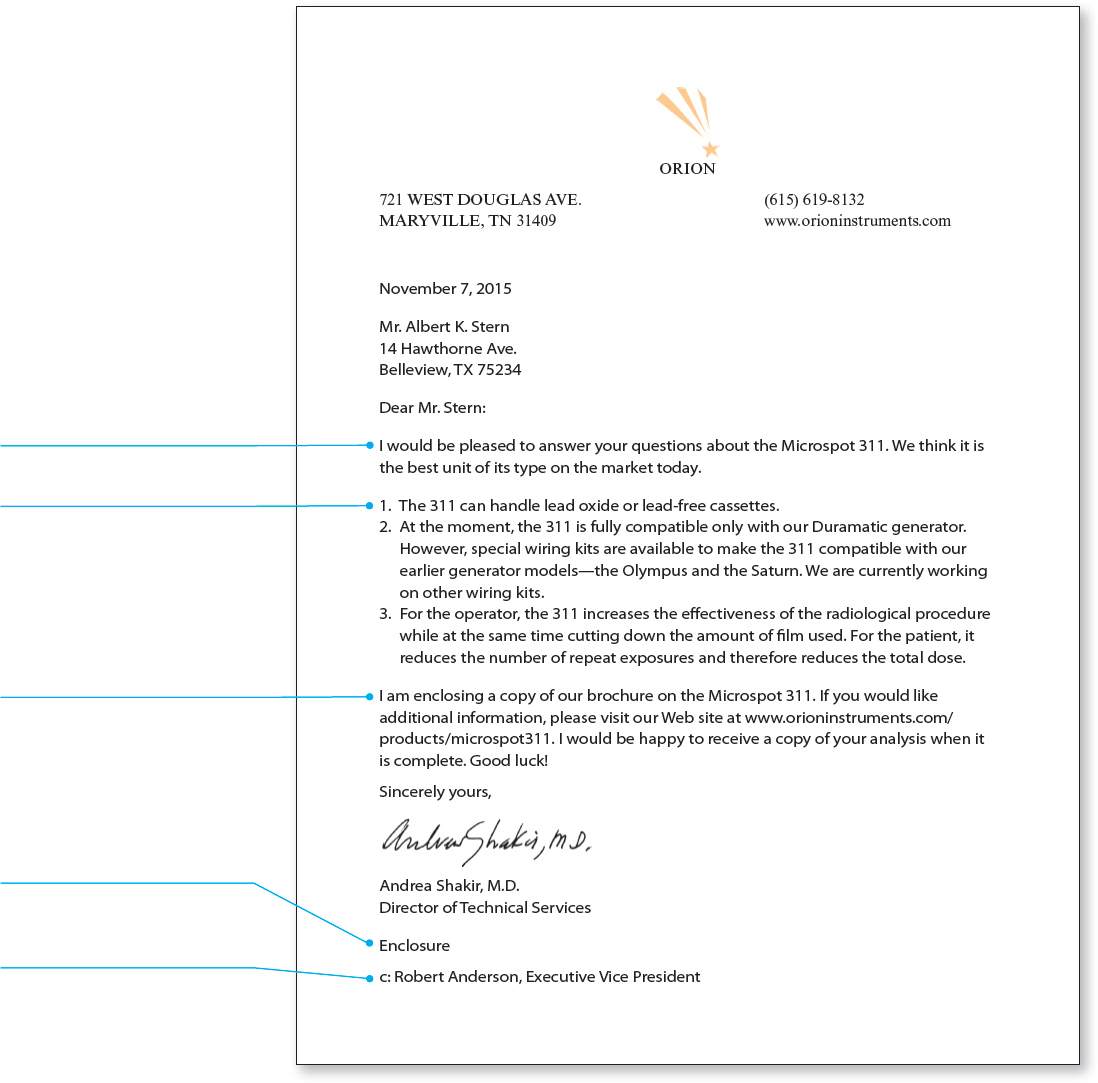

Response to an Inquiry Figure 14.6 shows a response to the inquiry letter in Figure 14.5.

The writer responds graciously.

The writer answers the three questions posed in the inquiry letter.

The writer encloses other information to give the reader a fuller understanding of the product.

The writer uses the enclosure notation to signal that she is attaching an item to the letter.

The writer indicates that she is forwarding a copy to her supervisor.

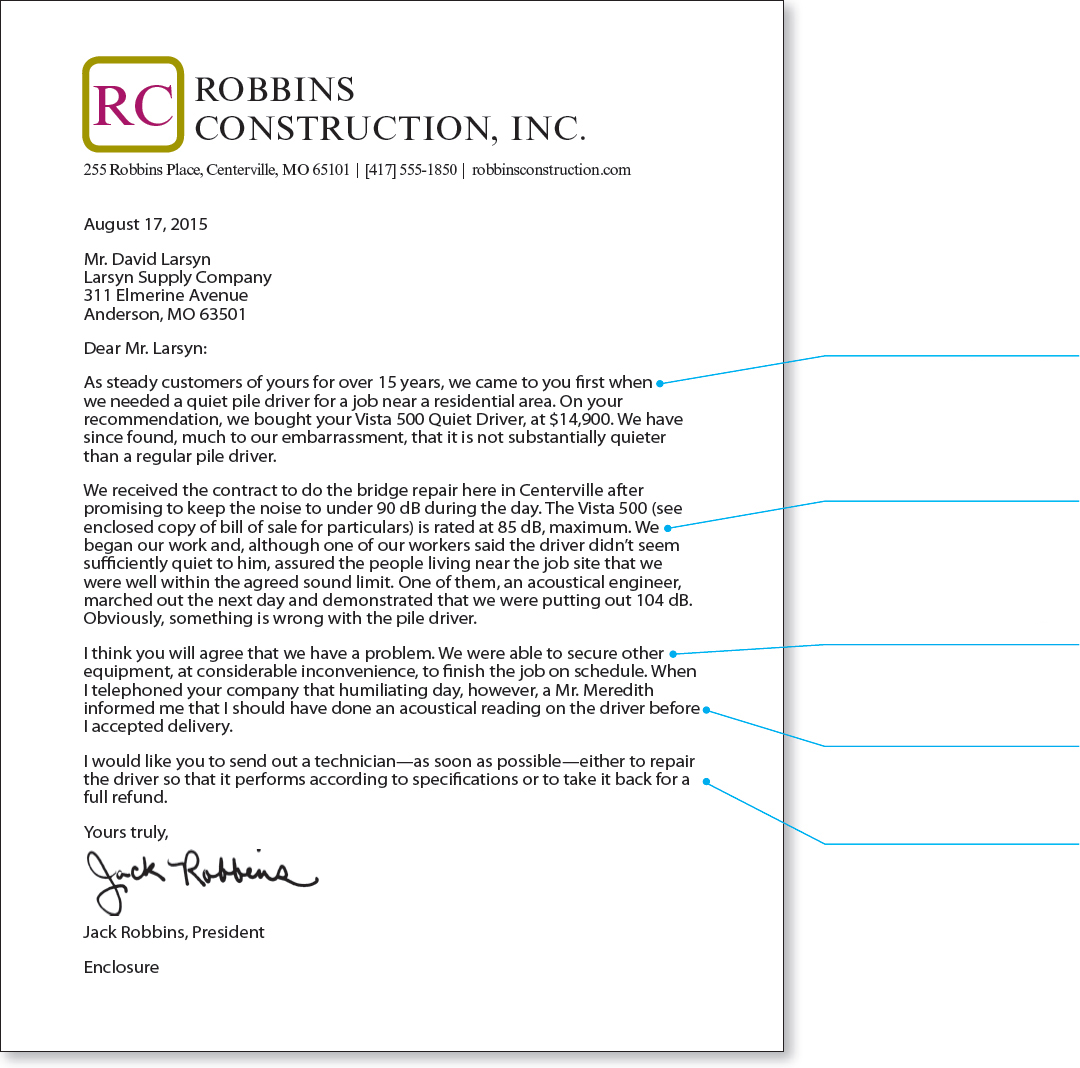

Claim Letter Figure 14.7 is an example of a claim letter that the writer scanned and attached to an email to the reader. The writer’s decision to present his message in a letter rather than an email suggests that he wishes to convey the more-formal tone associated with letters—and yet he wants the letter to arrive quickly.

The writer indicates clearly in the first paragraph that he is writing about an unsatisfactory product. Note that he identifies the product by model name.

The writer presents the background, filling in specific details about the problem. Notice how he supports his earlier claim that the problem embarrassed him professionally.

The writer states that he thinks the reader will agree that there was a problem with the equipment.

Then the writer suggests that the reader’s colleague did not respond satisfactorily.

The writer proposes a solution: that the reader take appropriate action. The writer’s clear, specific account of the problem and his professional tone increase his chances of receiving the solution he proposes.

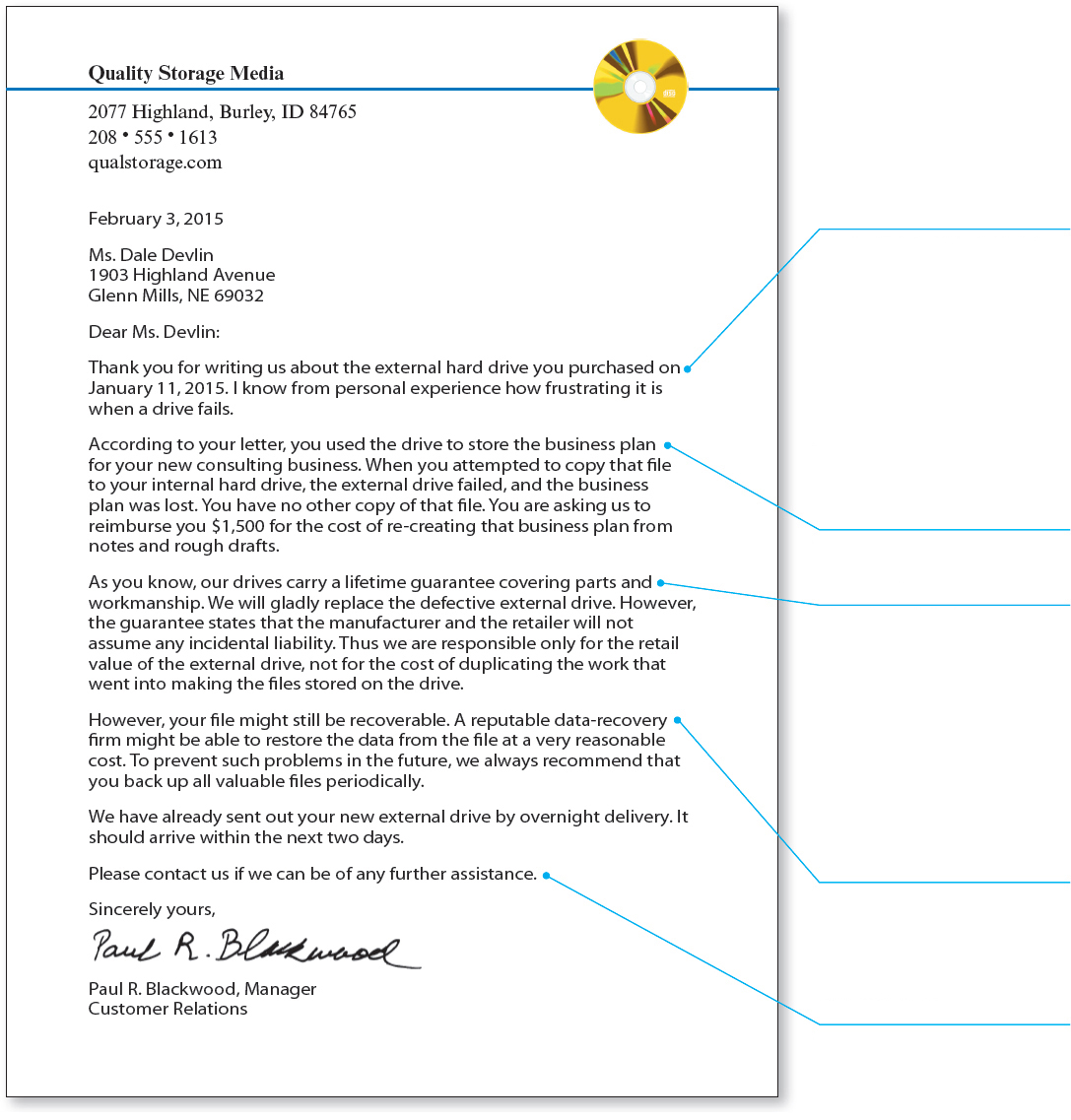

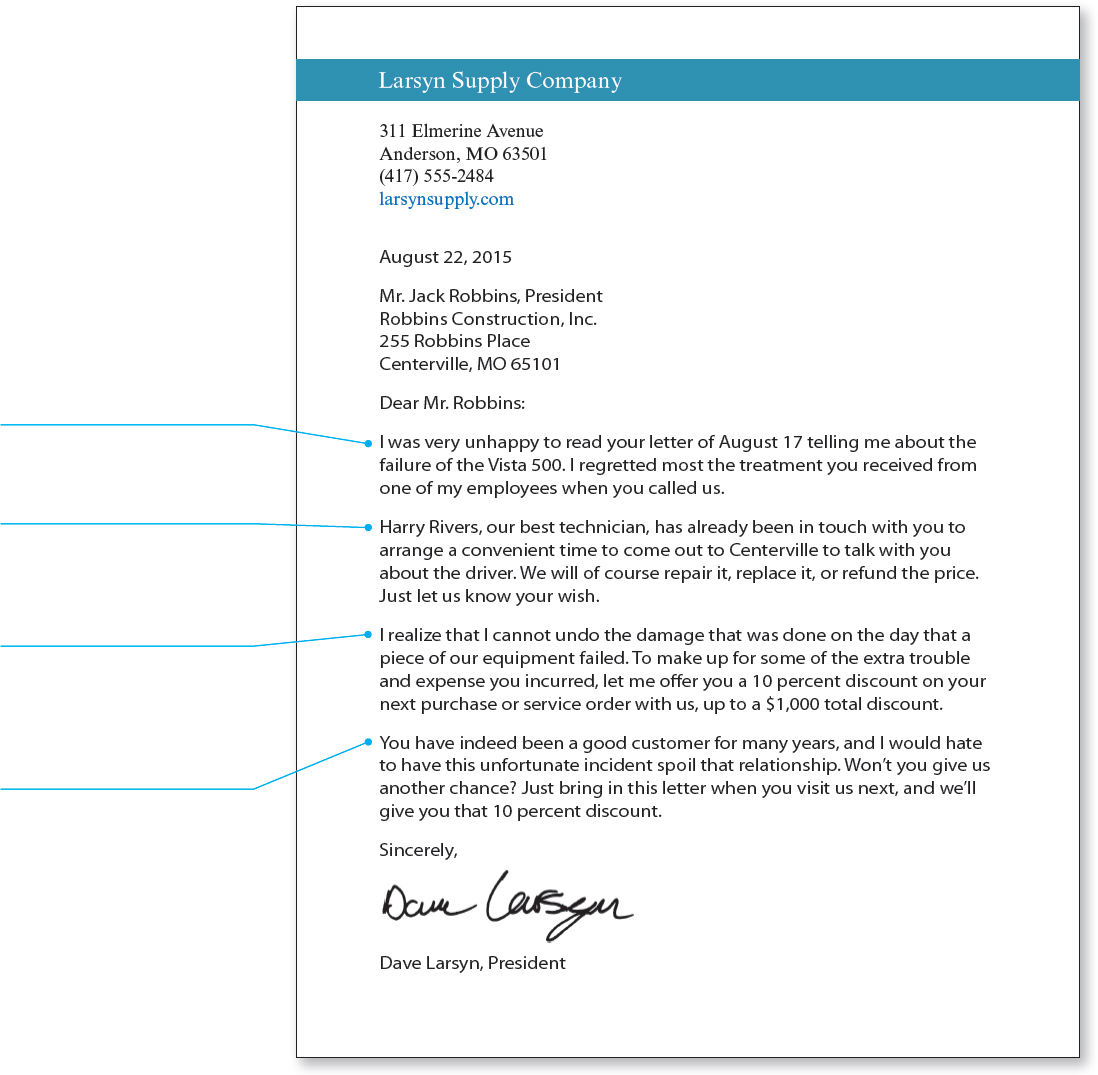

An adjustment letter, a response to a claim letter, tells the customer how you plan to handle the situation. Your purpose is to show that your organization is fair and reasonable and that you value the customer’s business.

If you can grant the request, the letter is easy to write. Express your regret, state the adjustment you are going to make, and end on a positive note by encouraging the customer to continue doing business with you.

The writer wisely expresses regret about the two problems cited in the claim letter.

The writer describes the actions he has already taken and formally states that he will do whatever the reader wishes.

The writer expresses empathy in making the offer of adjustment. Doing so helps to create a bond: you and I are both professionals who rely on our good reputations.

This polite conclusion appeals to the reader’s sense of fairness and good business practice.

If you are writing a “bad news” adjustment letter, salvage as much goodwill as you can by showing that you have acted reasonably. In denying a request, explain your side of the matter, thus educating the customer about how the problem occurred and how to prevent it in the future.

The writer does not begin by stating that he is denying the reader’s request. Instead, he begins politely by trying to form a bond with the reader. In trying to meet the customer on neutral ground, be careful about admitting that the customer is right. If you say “We are sorry that the engine you purchased from us is defective,” it will bolster the customer’s claim if the dispute ends up in court.

The writer summarizes the facts of the incident, as he sees them.

The writer explains that he is unable to fulfill the reader’s request. Notice that the writer never explicitly denies the request. It is more effective to explain why granting the request is not appropriate. Also notice that the writer does not explicitly say that the reader failed to make a backup copy of the plan and therefore the problem is her fault.

The writer shifts from the bad news to the good news. The writer explains that he has already responded appropriately to the reader’s request.

The writer ends with a polite conclusion. A common technique is to offer the reader a special discount on another, similar product.