GUIDE TO READING

Analyzing Remembered Event Essays

As you read the selections in this chapter, you will see how different authors craft stories about an important event in their lives.

Jean Brandt looks back on getting caught shoplifting.

Annie Dillard recalls the consequences of a childhood prank.

Jenée Desmond-Harris reflects on the death of her idol, rapper Tupac Shakur.

Peter Orner struggles to understand why he swiped something his father valued.

Analyzing how these writers tell a dramatic, well-

Determine the writer’s purpose and audience.

Many people write about important events in their lives to archive their memories and to learn something about themselves. Choosing events that are important to them personally, writers strive to imbue their stories with meaning and feeling that will resonate with readers. That is, they seek to help readers appreciate what we call the event’s autobiographical significance— why the event is so memorable for the writer and what it might mean for readers. Often writers use autobiographical stories to reflect on a conflict that remains unresolved or one they still do not fully understand. Autobiographical stories may not only prompt readers to reflect on the writer’s complicated and ambivalent emotions, puzzling motivations, and strained relationships. They may also help readers see larger cultural themes in these stories or understand implications the writer may not even have considered.

When reading the selections about remembered events that follow, ask yourself questions like these:

What seems to be the writer’s purpose (or multiple, perhaps even conflicting purposes)?

to understand what happened and why, perhaps to confront unconscious and possibly uncomplimentary motives?

to relive an intense experience that might resonate with readers and lead them to reflect on similar experiences of their own?

to win over readers, perhaps to justify or rationalize choices made, actions taken, or words used?

to use personal experience as an example that readers are likely to understand?

to reflect on cultural attitudes at the time the event occurred, perhaps in contrast to current ways of thinking?

How does the author want readers to react?

to understand or empathize with the writer?

to think anew about a similar experience of their own?

to see the writer’s experience as symptomatic of a broader social phenomenon?

to assess how well the story applies to other people and situations?

Assess the genre’s basic features.

![]() Basic Features

Basic Features

A Well-

Vivid Description

Significance

As you read about the remembered events in this chapter, analyze and evaluate how different authors use the basic features of the genre. The examples that follow are taken from the reading selections that appear later in this Guide to Reading.

A WELL-

Read first to see how the story attempts to engage readers:

by letting readers into the storyteller’s (or narrator’s) point of view (for example, by using the first-

person pronoun I to narrate the story); by arousing curiosity and suspense;

by clarifying or resolving the underlying conflict through a change or discovery of some kind.

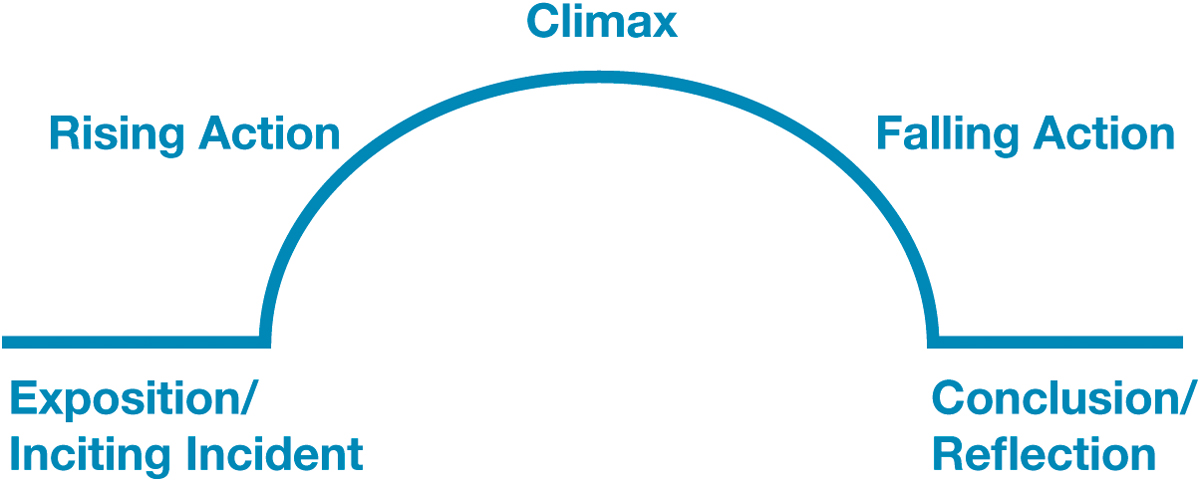

Many of these basic narrative elements can be visualized in the form of a dramatic arc (see Figure 2.1), which you can analyze to see how a story creates and resolves dramatic tension.

Exposition/Inciting Incident: Background information and scene setting, introducing the characters and the initial conflict or problem that sets off the action, arousing curiosity and suspense

Rising Action: The developing crisis, possibly leading to other conflicts and complications

Climax: The emotional high point, often a turning point marking a change for good or ill

Falling Action: Resolution of tension and unraveling of conflicts; may include a final surprise

Conclusion/Reflection: Conflicts come to an end but may not be fully resolved, and writer may reflect on the event’s meaning and importance—

Notice the narrating strategies used to create action sequences. Narrating action sequences relies on such strategies as using action verbs (such as walked) in different tenses or in conjunction with prepositional phrases or other cues of time or location to depict movement and show the relation among actions in time. In the following example, notice that I walked occurred in the past — after I had found and before I was about to drop it:

Action verbs

I walked back to the basket where I had found the button and was about to drop it when suddenly, instead, I took a quick glance around, assured myself no one could see, and slipped the button into the pocket of my sweatshirt. (Brandt, par. 3)

In addition to moving the narrative along, action sequences may also contribute to the overall or dominant impression and help readers understand the event’s significance. In this example, Brandt’s actions show her ambivalence or inner conflict. While her actions seem impulsive (“suddenly”), they are also self-

VIVID DESCRIPTION OF PEOPLE AND PLACES

For more on describing strategies, see Chapter 15.

Look for the describing strategies of naming, detailing, and comparing. In this example, Annie Dillard uses all three strategies to create a vivid description of a Pittsburgh street on one memorable winter morning:

Naming

Detailing

Comparing

The cars’ tires laid behind them on the snowy street a complex trail of beige chunks like crenellated castle walls. I had stepped on some earlier; they squeaked. (Dillard, par. 5)

Notice the senses the description evokes. In the example above, Dillard relies mainly on visual details to identify color, texture, and shape of the snowy tire tracks. But she also tells us what the chunks of snow sounded like when stepped on.

Think about the impression made by the descriptions, particularly by the comparisons (similes and metaphors). For example, Dillard’s comparison of tire tracks to crenellated castle walls suggests a kind of starry-

Finally, notice how dialogue is used to portray people and their relationships. Autobiographers use dialogue to characterize the people involved in the event, showing what they’re like by depicting how they talk and interact. Speaker tags identify who is speaking and indicate the speaker’s tone or attitude. Here’s a brief example that comes at the climax of Dillard’s story when the man finally catches the kids he’s been chasing:

Speaker tag

“You stupid kids,” he began perfunctorily. (Dillard, par. 18)

Consider why the writer chose to quote, paraphrase, or summarize. Quoting can give dialogue immediacy, intensify a confrontation, and shine a spotlight on a relationship. For example, Brandt uses quoting to make an inherently dramatic interaction that much more intense.

“I don’t understand. What did you take? Why did you do it? You had plenty of money with you.”

“I know but I just did it. I can’t explain why. Mom, I’m sorry.”

“I’m afraid sorry isn’t enough. I’m horribly disappointed in you.” (pars. 33–35)

Paraphrasing enables the writer to choose words for their impact or contribution to the dominant impression.

Paraphrase cue

Next thing I knew, he was talking about calling the police and having me arrested and thrown in jail, as if he had just nabbed a professional thief instead of a terrified kid. (Brandt, par. 7)

The clichés (thrown in jail and nabbed) mock the security guard, aligning Brandt with her father’s criticism of the police at the story’s end.

Summarizing gives the gist. Sometimes writers use summary because what was said or how it was said isn’t as important as the mere fact that something was said:

Summary cue

. . . the chewing out was redundant, a mere formality, and beside the point. (Dillard, par. 19)

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Look for remembered feelings and thoughts from the time the event occurred. Notice in the first example that Brandt announces her thoughts and feelings before describing them, but in the second example she simply shows her feelings by her actions:

Emotional response

The thought of going to jail terrified me. . . .

Long after we got off the phone,. . . I could still distinctly hear the disappointment and hurt in my mother’s voice. I cried. (36)

Look also for present perspective reflections about the past. In this example, Desmond-

Rhetorical questions

Did we take ourselves seriously? Did we feel a real stake in the life of this “hard-

Notice that writers sometimes express both their past and present feelings, possibly to contrast them or to show that they have not changed. Observe the time cues Orner and Desmond-

Time cues

Now that he is older and far milder, it is hard to believe how scared I used to be of my father. (Orner, par. 8)

I mourned Tupac’s death then, and continue to mourn him now, because his music represents the years when I was both forced and privileged to confront what it meant to be black. (Desmond-

Mark word choices in descriptive and narrative passages that contribute to the dominant impression and help to show why the event or person was significant. For example, Brandt shows her feeling of shame vividly in this passage:

As the officers led me through the mall, I sensed a hundred pairs of eyes staring at me. My face flushed and I broke out in a sweat. (par. 18)

Consider whether the story’s significance encompasses mixed or ambivalent feelings and still-

Right after shoplifting, Brandt tells us “I thought about how sly [I] had been” and that “I felt proud of [my] accomplishment” (par. 5).

After she is arrested, she acknowledges mixed feelings: “Being searched, although embarrassing, somehow seemed to be exciting. . . .

I was having fun” (19). It is only when she has to face her mother that Brandt lets her intense feelings show: “For the first time that night, I was close to tears” (26).

At the end, however, by transferring the blame from Brandt to the police, her father seems to leave the conflict essentially unresolved and repressed: “Although it would never be forgotten, the incident was not mentioned again” (38).