Instructor's Notes

- To add the “Make Connections” activity as a discussion prompt, click on “Add to This Unit,” select “Create New,” choose “Discussion Board,” and then paste the text into the text box.

- To assign the Analyze and Write activities following the reading, click on the “Browse Resources for this Unit” button or navigate to the “Resources” panel.

- An autograded multiple-

choice quiz, a summary activity with a sample summary as feedback, and a synthesis activity are available for this reading; click on the “Browse Resources for this Unit” button or navigate to the “Resources” panel to find those and other resources for this chapter.

Jenée Desmond-Harris Tupac and My Non-thug Life

JENÉE DESMOND-

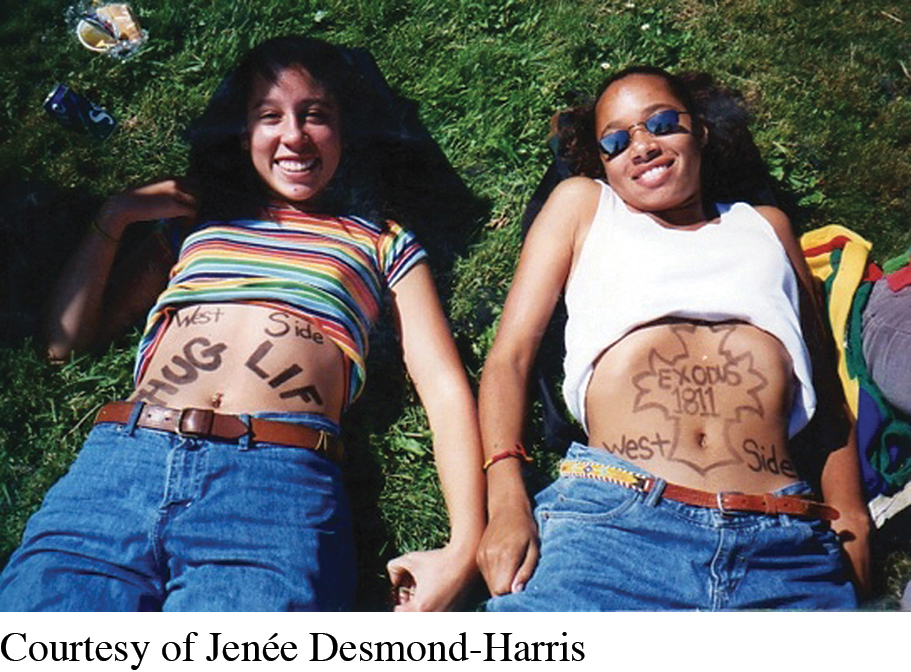

As you read, consider the photograph that appeared in the article:

What does the photograph capture about the fifteen-

year- old Desmond- Harris? What does its inclusion say about Desmond-

Harris’s perspective on her adolescent self and the event she recollects?

1

I learned about Tupac’s death when I got home from cheerleading practice that Friday afternoon in September 1996. I was a sophomore in high school in Mill Valley, Calif. I remember trotting up my apartment building’s stairs, physically tired but buzzing with the frenetic energy and possibilities for change that accompany fall and a new school year. I’d been cautiously allowing myself to think during the walk home about a topic that felt frighteningly taboo (at least in my world, where discussion of race was avoided as delicately as obesity or mental illness): what it meant to be biracial and on the school’s mostly white cheerleading team instead of the mostly black dance team. I remember acknowledging, to the sound of an 8-

2

My private musings on identity and belonging — not original in the least, but novel to me — were interrupted when my mom heard me slam the front door and drop my bags: “Your friend died!” she called out from another room. Confused silence. “You know, that rapper you and Thea love so much!”

Mourning a Death in Vegas

3

The news was turned on, with coverage of the deadly Vegas shooting. Phone calls were made. Ultimately my best friend, Thea, and I were left to our own 15-

4

We couldn’t “pour out” much alcohol undetected for a libation, so we limited ourselves to doing somber shots of liqueur from a well-

5

On a sound system that echoed through speakers perched discreetly throughout the airy house, we played “Life Goes On” on a loop and sobbed. We analyzed lyrics for premonitions of the tragedy. We, of course, cursed Biggie. Who knew that the East Coast–West Coast war had two earnest soldiers in flannel pajamas, lying on a king-

6

A snapshot taken that Monday on our high school’s front lawn (seen here) shows the two of us lying side by side, shirts lifted to display the tributes in black marker. Despite our best efforts, it’s the innocent, bubbly lettering of notes passed in class and of poster boards made for social studies presentations. My hair has recently been straightened with my first (and last) relaxer and a Gold ’N Hot flatiron on too high a setting. Hers is slicked back with the mixture of Herbal Essences and Blue Magic that we formulated in a bathroom laboratory.

7

My rainbow-

Mixed Identities: Tupac and Me

8

Did we take ourselves seriously? Did we feel a real stake in the life of this “hard-

9

I mourned Tupac’s death then, and continue to mourn him now, because his music represents the years when I was both forced and privileged to confront what it meant to be black. That time, like his music, was about exploring the contradictory textures of this identity: The ambience and indulgence of the fun side, as in “California Love” and “Picture Me Rollin’.” But also the burdensome anxiety and outright anger — “Brenda’s Got a Baby,” “Changes” and “Hit ’Em Up.”

10

For Thea and me, his songs were the musical score to our transition to high school, where there emerged a vague, lunchtime geography to race: White kids perched on a sloping green lawn and the benches above it. Below, black kids sat on a wall outside the gym. The bottom of the hill beckoned. Thea, more outgoing, with more admirers among the boys, stepped down boldly, and I followed timidly. Our formal invitations came in the form of unsolicited hall passes to go to Black Student Union meetings during free periods. We were assigned to recite Maya Angelou’s “Phenomenal Woman” at the Black History Month assembly.

11

Tupac was the literal sound track when our school’s basketball team would come charging onto the court, and our ragtag group of cheerleaders kicked furiously to “Toss It Up” in a humid gymnasium. Those were the games when we might breathlessly join the dance team after our cheer during time-

Everything Black — and Cool

12

. . . Blackness became something cool, something to which we had brand-

13

Tupac’s music, while full of social commentary (and now even on the Vatican’s playlist), probably wasn’t made to be a treatise on racial identity. Surely it wasn’t created to accompany two girls (little girls, really) as they embarked on a coming-

[REFLECT]

Make connections: Searching for identity.

Remembering high school, Desmond-

School, particularly high school, is notorious for students’ forming peer groups or cliques of various kinds—

Did you associate with any particular groups, and if so, why did you choose these groups?

How did being in a particular group or not being in that group affect your sense of yourself?

Why do you think it is important for her “coming-

of- age journey” that Desmond- Harris felt that the group at the “bottom of the hill beckoned” (par. 10)? The word beckoned here can be read in two ways: that she felt the need to be a part of the group or that members of the group invited her to join them. Consider how these possible interpretations affect your understanding of her remembered event.

[ANALYZE]

Use the basic features.

A WELL-

We have seen that the dramatic arc (Fig. 2.1) is often used to organize a remembered event narrative around a central conflict, arousing curiosity and suspense as it builds toward a climax or emotional high point before resolving the conflict or at least bringing it to a conclusion. This is basically the structure Brandt and Dillard use to tell their stories. Writers, however, do not always follow this straightforward pattern. They may emphasize certain elements of the arc and downplay or even skip others.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing the structure of Tupac and My Non-thug Life.

Desmond-

Harris could have built up to the surprising news of Tupac’s death, using it as the dramatic climax of her story. Why do you think she chose instead to use his death as the “inciting incident” with which to begin her story? How does the opening paragraph shed light on the conflict at the heart of Desmond-

Harris’s story? What do the girls’ actions as they mourn Tupac’s death (paragraphs 3–7) as well as their actions later (paragraphs 10 –12) suggest about how the inciting incident of Tupac’s death led them to deal with the underlying conflict?

VIVID DESCRIPTION OF PEOPLE AND PLACES: USING VISUALS AND BRAND NAMES

Desmond-

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph or two analyzing Desmond-

Skim paragraphs 5–7, highlighting the specific details in the photo that Desmond-

Harris points out as well as the brand names (usually capitalized) and the modifiers (as in skater- inspired ) that make them more specific.Look closely at the photograph itself, and consider its purpose.

Why do you think Desmond-

Harris included it? What does the photograph contribute or show us that the text alone does not convey?

Consider the effect that the photo and the brand names have on you as a reader (or might have on readers of about Desmond-

Harris’s age). How do they help readers envision the girls? What is the dominant impression you get of the young Desmond Harris from these descriptive details?

For more about analyzing visuals, see Chapter 28.

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SIGNIFICANCE: HANDLING COMPLEX EMOTIONS

Remembered events that have lasting significance nearly always involve mixed or ambivalent feelings. Therefore, readers expect and appreciate some degree of complexity. Multiple layers of meaning make autobiographical stories more, not less, interesting. Significance that seems simplistic or predictable makes stories less successful. For example, if Brandt’s story had ended with her arrest and left out the conversations with her parents, readers would have less insight into Brandt’s still intense and unresolved feelings.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph or two analyzing Desmond-

Skim the last two sections (pars. 8 –13), noting passages where Desmond-

Harris tells readers her remembered feelings and thoughts at the time and her present perspective as an adult reflecting on the experience. How does Desmond- Harris use her dual perspective— that of the fifteen- year- old experiencing the event and the thirty- year- old writing about it— to help readers understand the event’s significance? Look closely at paragraph 8, and consider how Desmond-

Harris helps her readers grasp the significance of the event by using sentence strategies like these: rhetorical questions (questions writers ask and answer themselves)

repeated words and phrases

intentional sentence fragments (incomplete sentences used for special effect)

Note that in academic writing, sentence fragments—

[RESPOND]

Consider possible topics: Recognizing a public event as a turning point.

Like Desmond-