Instructor's Notes

- The “Make Connections” activity can be used as a discussion board prompt by clicking on “Add to This Unit,” selecting “Create New,” choosing “Discussion Board,” and then pasting the “Make Connections” activity into the text box.

- The basic features (“Analyze and Write”) activities following this reading, as well as an autograded multiple-

choice quiz, a summary activity with a sample summary as feedback, and a synthesis activity for this reading, can be assigned by clicking on the “Browse Resources for the Unit” button or navigating to the “Resources” panel.

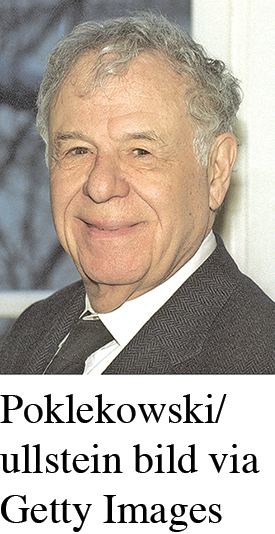

Amitai Etzioni Working at McDonald’s

AMITAI ETZIONI is a sociologist who has taught at Columbia, Harvard, and George Washington University, where he currently directs the Institute for Communitarian Policy Studies. He has written numerous articles and more than two dozen books, including The Spirit of Community: The Reinvention of American Society (1983); The Limits of Privacy (2004); Security First: For a Muscular, Moral Foreign Policy (2007); and most recently, The New Normal: Finding a Balance between Individual Rights and the Common Good (2014). The following reading was originally published on the opinion page of the Miami Herald newspaper.

As you read, consider the following:

What do you imagine Etzioni’s teenage son Dari, who helped his father write the essay, contributed?

What kinds of summer and school-

year jobs, if any, have you and your friends held while in high school or college?

1

M cDonald’s is bad for your kids. I do not mean the flat patties and the white-

2

As many as two-

3

At first, such jobs may seem right out of the Founding Fathers’ educational manual for how to bring up self-

Far from providing opportunities for entrepreneurship . . . most teen jobs these days are highly structured.

4

It has been a longstanding American tradition that youngsters ought to get paying jobs. In folklore, few pursuits are more deeply revered than the newspaper route and the sidewalk lemonade stand. Here the youngsters are to learn how sweet are the fruits of labor and self-

5

Roy Rogers, Baskin Robbins, Kentucky Fried Chicken, et al. may at first seem nothing but a vast extension of the lemonade stand. They provide very large numbers of teen jobs, provide regular employment, pay quite well compared to many other teen jobs and, in the modern equivalent of toiling over a hot stove, test one’s stamina.

6

Closer examination, however, finds the McDonald’s kind of job highly uneducational in several ways. Far from providing opportunities for entrepreneurship (the lemonade stand) or self-

7

True, you still have to have the gumption to get yourself over to the hamburger stand, but once you don the prescribed uniform, your task is spelled out in minute detail. The franchise prescribes the shape of the coffee cups; the weight, size, shape and color of the patties; and the texture of the napkins (if any). Fresh coffee is to be made every eight minutes. And so on. There is no room for initiative, creativity, or even elementary rearrangements. These are breeding grounds for robots working for yesterday’s assembly lines, not tomorrow’s high-

8

There are very few studies on the matter. One of the few is a 1984 study by Ivan Charper and Bryan Shore Fraser. The study relies mainly on what teen-

9

What does it matter if you spend 20 minutes to learn to use a cash register, and then — “operate” it? What “skill” have you acquired? It is a long way from learning to work with a lathe or carpenter tools in the olden days or to program computers in the modern age.

10

A 1980 study by A. V. Harrell and P. W. Wirtz found that, among those students who worked at least 25 hours per week while in school, their unemployment rate four years later was half of that of seniors who did not work. This is an impressive statistic. It must be seen, though, together with the finding that many who begin as part-

11

Some say that while these jobs are rather unsuited for college-

12

The hours are often long. Among those 14 to 17, a third of fast-

13

Often the stores close late, and after closing one must clean up and tally up. In affluent Montgomery County, Md., where child labor would not seem to be a widespread economic necessity, 24 percent of the seniors at one high school in 1985 worked as much as five to seven days a week; 27 percent, three to five. There is just no way such amounts of work will not interfere with school work, especially homework. In an informal survey published in the most recent yearbook of the high school, 58 percent of seniors acknowledged that their jobs interfere with their school work.

14

The Charper-

15

Supervision is often both tight and woefully inappropriate. Today, fast-

16

There is no father or mother figure with which to identify, to emulate, to provide a role model and guidance. The work-

17

The pay, oddly, is the part of the teen work-

18

Where this money goes is not quite clear. Some use it to support themselves, especially among the poor. More middle-

19

One may say that this is only fair and square; they are being good American consumers and spend their money on what turns them on. At least, a cynic might add, these funds do not go into illicit drugs and booze. On the other hand, an educator might bemoan that these young, yet unformed individuals, so early in life driven to buy objects of no intrinsic educational, cultural or social merit, learn so quickly the dubious merit of keeping up with the Joneses in ever-

20

Many teens find the instant reward of money, and the youth status symbols it buys, much more alluring than credits in calculus courses, European history or foreign languages. No wonder quite a few would rather skip school — and certainly homework — and instead work longer at a Burger King. Thus, most teen work these days is not providing early lessons in the work ethic; it fosters escape from school and responsibilities, quick gratification and a short cut to the consumeristic aspects of adult life.

21

Thus, parents should look at teen employment not as automatically educational. It is an activity — like sports —that can be turned into an educational opportunity. But it can also easily be abused. Youngsters must learn to balance the quest for income with the needs to keep growing and pursue other endeavors that do not pay off instantly — above all education.

22

Go back to school.

[REFLECT]

Make connections: Useful job skills.

Etzioni argues that fast-

To judge Etzioni’s argument against your own experience and expectations, consider what you have learned or expect people to learn from summer and after-

Which, if any, of the skills and habits Etzioni lists as important do you think young people learn at summer or after-

school jobs? Why do you think these skills and habits are worth learning? If you think other skills and habits are as important or even more important, explain what they are and why you think so.

[ANALYZE]

Use the basic features.

A FOCUSED, WELL-

When Jessica Statsky wrote “Children Need to Play, Not Compete,” she knew she would be addressing her classmates. But writers of position essays do not always have such a homogeneous audience. Often, they have to direct their argument to a diverse group of readers, many of whom do not share their concerns or values. From the first sentence, it is clear that Etzioni’s primary audience is the parents of teenagers, but his concluding sentence is a direct address to the teenagers themselves: “Go back to school.”

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing and evaluating how Etzioni presents the issue to a diverse group of readers:

Reread paragraphs 1–7, highlighting the qualities—

values and skills— associated with traditional jobs (the newspaper route and lemonade stand of yesteryear) and with today’s McDonald’s- type jobs, at least according to Etzioni. How does Etzioni use this comparison to persuade parents to reconsider their assumption that McDonald’s- type jobs are good for their kids? Page 251Now skim the rest of the essay, looking for places where Etzioni appeals to teenagers themselves. (Notice, for example, how he represents teenagers’ experience and values.) How effective do you think Etzioni’s appeal would be to teenage readers? How effective do you think it would be for you and your classmates?

A WELL-

Numbers can seem impressive — as, for example, when Jessica Statsky refers to the research finding that about 90 percent of children would choose to play regularly on a losing team rather than sit on the bench of a winning team (par. 5). However, without knowing the size of the sample (90 percent of 10 people, 100 people, or 10,000 people?), it is impossible to judge the significance of the statistic. Moreover, without knowing who the researchers are and how their research was funded and conducted, it is also difficult to judge the credibility of the statistic. That’s why most critical readers want to know the source of statistics to see whether the research is peer-

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing and evaluating Etzioni’s use of statistics.

Reread paragraphs 8–14, and highlight the statistics Etzioni uses. What is each statistic being used to illustrate or prove?

Identify what you would need to know about these research studies before you could accept their statistics as credible. Consider also what you would need to know about Etzioni himself before you could decide whether to rely on statistics he calls “impressive” (par. 10). How does your personal experience and observation influence your decision?

AN EFFECTIVE RESPONSE: PRESENTING AND REINTERPRETING EVIDENCE TO UNDERMINE OBJECTIONS

At key points throughout his essay, Etzioni acknowledges readers’ likely objections and then responds to them. One strategy Etzioni uses is to cite research that appears to undermine his claim and then offer a new interpretation of that evidence. For example, he cites a study by Harrell and Wirtz (par. 10) that links work as a student with greater likelihood of employment later on. He then reinterprets the data from this study to show that the high likelihood of future employment could be an indication that workers in fast-

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph or two analyzing and evaluating Etzioni’s strategy of reinterpreting data elsewhere in his essay:

Reread paragraphs 8–9, in which Etzioni responds to the claim that employees in McDonald’s-

type jobs develop many useful skills. Reread paragraphs 14–16, in which Etzioni discusses the benefits and shortcomings of various kinds of on-

the- job supervision. Identify the claim that appears in the research Etzioni cites. How does Etzioni reinterpret it? Do you find his reinterpretation persuasive? Why or why not?

A CLEAR, LOGICAL ORGANIZATION: PROVIDING CUES FOR READERS

Writers of position arguments generally try to make their writing logical and easy to follow. Providing cues, or road signs — for example, by forecasting their reasons in a thesis statement early in the argument, using topic sentences to announce each reason as it is supported, and employing transitions (such as furthermore, in addition, and finally) to guide readers from one point to another — can be helpful, especially in newspaper articles, the readers of which do not want to spend a lot of time deciphering arguments.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing and evaluating the cueing strategies Etzioni uses to help his readers follow his argument:

Find and highlight his thesis statement, the cues forecasting his reasons, the transitions he provides, and any other cueing devices Etzioni uses.

Identify the paragraphs in which Etzioni develops each of his reasons.

How does Etzioni help readers track his reasons, and how effective are his cues?

[RESPOND]

Consider possible topics: Issues facing students.

Etzioni focuses on a single kind of part-