Making logical appeals

Page contents:

While the way you present your character in writing always exerts a strong appeal (or lack of appeal) in an argument, credibility alone cannot and should not carry the full burden of convincing readers. Indeed, many are inclined to think that the logic of the argument—

Examples

Examples are used most often to support generalizations or to bring abstractions to life. In an argument about American mass media and body image, for instance, you might make the general statement that popular media send the message that a woman must be thin to be attractive; you might then illustrate your generalization with these examples:

At the supermarket checkout, a tabloid publishes unflattering photographs of a young singer and comments on her apparent weight gain in shocked captions that ask “What happened?!?” Another praises a starlet for quickly shedding “ugly pounds” after the recent birth of a child. The cover of Cosmopolitan features a glamorously made-

Precedents

Precedents are particular kinds of examples taken from the past. The most common use of precedent occurs in law, where an attorney may ask for a certain ruling based on a similar earlier case. Precedent appears in everyday arguments as well. If, as part of a proposal for increasing lighting in the library garage, you point out that the university has increased lighting in four other garages in the past year, you are arguing on the basis of precedent.

In research writing, you must identify your sources for any examples or precedents not based on your own knowledge.

The following questions can help you check any use of example or precedent:

How representative are the examples?

Are they sufficient in strength or number to lead to a generalization?

In what ways do they support your point?

How closely does the precedent relate to the point you’re trying to make? Are the situations really similar?

How timely is the precedent? (What would have been applicable in 1980 is not necessarily applicable today.)

Narratives

Because storytelling is universal, narratives can be persuasive in helping readers understand and accept the logic of an argument. Stories drawn from your own experience can particularly appeal to readers, for they not only help make your point in true-

When you include stories in your argument, ask yourself the following questions:

Does the narrative support your thesis?

Will the story’s significance to the argument be clear to your readers?

Is the story one of several good reasons or pieces of evidence—

or does it have to carry the main burden of the argument?

In general, do not rely solely on the power of stories to carry your argument; readers usually expect writers to state and argue their reasons more directly and abstractly as well. An additional danger if you use only your own experiences is that you can seem focused too much on yourself (and perhaps not enough on your readers).

As you develop your own arguments, keep in mind that although narratives can provide effective logical support, they may be used equally effectively for ethical or emotional appeals as well.

Appeals to authority and testimony

Another way to support an argument logically is to cite an authority. For more than fifty years, the use of authority has figured prominently in the controversy over smoking. Since the U.S. surgeon general’s 1964 announcement that smoking is hazardous to health, millions of Americans have quit smoking, largely persuaded by the authority of the scientists offering the evidence.

But as with other strategies for building support for an argumentative claim, citing authorities demands careful consideration. Ask yourself the following questions to be sure you are using authorities effectively:

Is the authority timely? (The argument that the United States should pursue a policy just because it was supported by Thomas Jefferson may fail because Jefferson’s time was so radically different from ours.)

Is the authority qualified to judge the topic at hand? (To cite a baseball player in an essay on banking practices, an appeal to false authority, would probably not strengthen your argument.)

Is the authority likely to be known and respected by readers? (To cite an unfamiliar authority without some identification will lessen the impact of the evidence.)

Are the authority’s credentials clearly stated and verifiable? (Especially with web-

based sources, it is crucial to know whose authority guarantees the reliability of the information.)

Authorities are commonly cited in research-

Testimony—

Causes and effects

Tracing causes often lays the groundwork for an argument, particularly if the effect of the causes is one we would like to change. In an environmental science class, for example, a student may argue that a national law regulating smokestack emissions from utility plants is needed because (1) acid rain on the East Coast originates from emissions at utility plants in the Midwest, (2) acid rain kills trees and other vegetation, (3) utility lobbyists have prevented midwestern states from passing strict laws controlling emissions from such plants, and (4) in the absence of such laws, acid rain will destroy a high percentage of eastern forests. In this case, the first point is that the emissions cause acid rain; the second, that acid rain causes destruction in eastern forests; and the third, that states have not acted to break the cause-

In fact, a cause-

Inductive and deductive reasoning

Traditionally, logical arguments are classified as using either inductive or deductive reasoning, but in practice, the two types of reasoning usually appear together. Inductive reasoning is the process of making a generalization based on a number of specific instances. If you find you are ill on ten occasions after eating shellfish, for example, you will likely draw the inductive generalization that shellfish makes you ill. It may not be an absolute certainty that shellfish was the culprit, but the probability lies in that direction.

Deductive reasoning, on the other hand, reaches a conclusion by assuming a general principle (known as a major premise) and then applying that principle to a specific case (the minor premise). In practice, this general principle is usually derived from induction. The inductive generalization Shellfish makes me ill, for instance, could serve as the major premise for the deductive argument Because all shellfish makes me ill, the shrimp on this buffet is certain to make me ill.

Syllogisms and enthymemes

Deductive arguments have traditionally been analyzed as syllogisms—

| MAJOR PREMISE | All people die. |

| MINOR PREMISE | I am a person. |

| CONCLUSION | I will die. |

Syllogisms are too rigid and absolute to serve in arguments about questions that have no absolute answers, and they often lack any appeal to an audience. Aristotle’s simpler alternative, the enthymeme, calls on the audience to supply the implied major premise. Consider the following example:

Because children who are bullied suffer psychological harm, schools should immediately discipline students who bully others.

You can analyze this enthymeme by restating it in the form of two premises and a conclusion.

| MAJOR PREMISE | Schools should immediately discipline students who harm other children. |

| MINOR PREMISE | Being bullied causes psychological harm to children. |

| CONCLUSION | Schools should immediately discipline students who bully other children. |

The writer can count on an audience agreeing with or supplying the major premise: safety and common sense demand that schools should discipline children who harm other students. This premise is assumed rather than stated in the enthymeme. By implicitly asking the audience to supply this premise to the argument, the writer engages the audience’s participation.

Conclusions from premises

A deductive conclusion is only as strong as the premises on which it is based. The citizen who argues that Ed is a crook and shouldn’t be elected to public office is arguing deductively, based on an implied major premise: No crook should be elected to public office. Most people would agree with this major premise. So the issue in this argument rests on the minor premise that Ed is a crook. Satisfactory proof of that premise will make us likely to accept the deductive conclusion that Ed shouldn’t be elected.

At other times, the unstated premise may be more problematic. The person who says Don’t bother to ask for Ramon’s help with physics—

Toulmin’s system

Philosopher Stephen Toulmin offers a variation on the syllogism and enthymeme that looks for claims, reasons, and assumptions rather than major and minor premises.

| CLAIM | Schools should immediately discipline students who bully other children. |

| REASON(S) | Being bullied causes psychological harm to children. |

| ASSUMPTION | Schools should discipline students who harm other children. |

Note that in this system, the assumption—

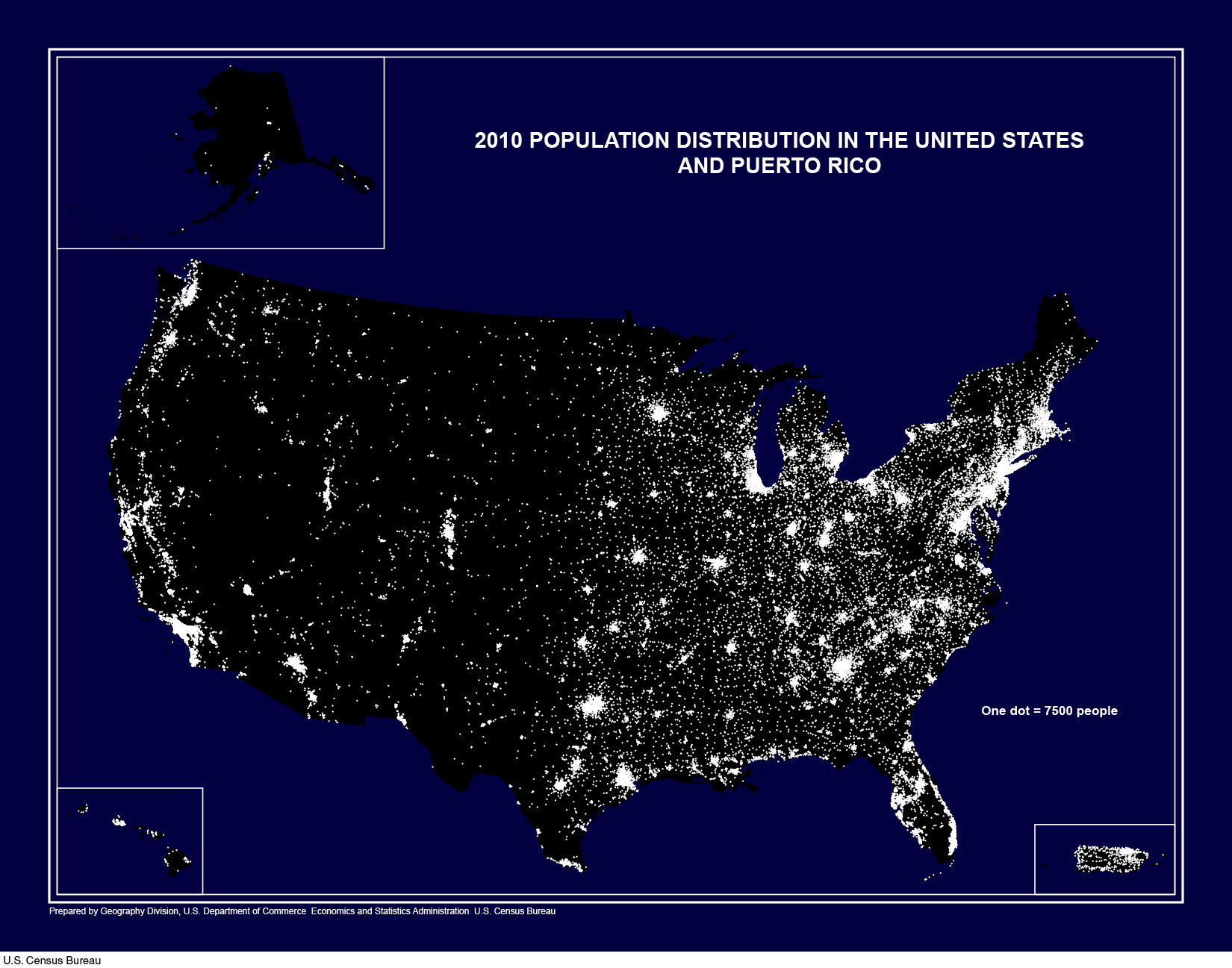

Sample: Logical appeals in a chart

Charts, graphs, tables, maps, photographs, and so on can be especially useful in arguments because they present factual information that can be taken in at a glance. The United States Census Bureau used the following graphic to show the nation's population distribution. Consider how long it would take to explain all the information in this chart with words alone.

A chart that makes a logical appeal