Some Procedures in Argument

DEFINITION

Definition, we mentioned in Chapter 1, is one of the classical topics, a “place” to which one goes with questions; in answering the questions, one finds ideas. When we define, we’re answering the question “What is it?” In answering this question as precisely as we can, we will find, clarify, and develop ideas.

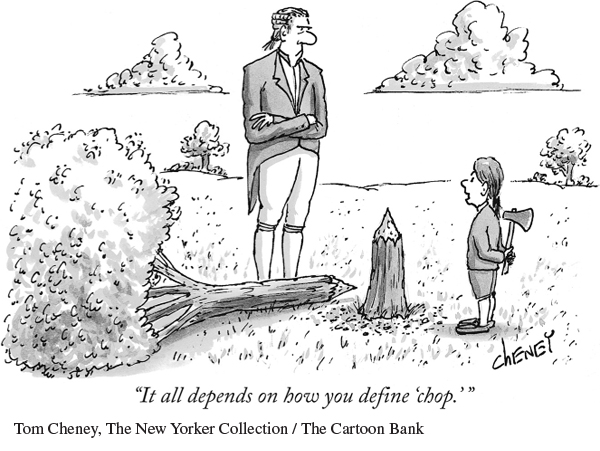

We have already glanced at an argument over the proposition that “all men are created equal,” and we saw that the words needed clarification. Equal meant, in the context, not physically or mentally equal but something like “equal in rights,” equal politically and legally. (And, of course, men meant “white men and women.”) Words don’t always mean exactly what they seem to mean: There’s no lead in a lead pencil, and a standard 2-by-4 is currently 15/8 inches in thickness and 33/8 inches in width.

DEFINITION BY SYNONYM Let’s return for a moment to pornography, a word that is not easy to define. One way to define a word is to offer a synonym. Thus, pornography can be defined, at least roughly, as “obscenity” (something indecent). But definition by synonym is usually only a start because then we have to define the synonym; besides, very few words have exact synonyms. (In fact, pornography and obscenity are not exact synonyms.)

DEFINITION BY EXAMPLE A second way to define a word is to point to an example (this is often called ostensive definition, from the Latin ostendere, “to show”). This method can be very helpful, ensuring that both writer and reader are talking about the same thing, but it also has limitations. A few decades ago, many people pointed to James Joyce’s Ulysses and D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover as examples of obscene novels, but today these books are regarded as literary masterpieces. It’s possible that they can be obscene and also be literary masterpieces. (Joyce’s wife is reported to have said of her husband, “He may have been a great writer, but … he had a very dirty mind.”)

One of the difficulties of using an example, however, is that the example is richer and more complex than the term it’s being used to define, and this richness and complexity get in the way of achieving a clear definition. Thus, if one cites Lady Chatterley’s Lover as an example of pornography, a reader may erroneously think that pornography has something to do with British novels (because Lawrence was British) or with heterosexual relationships outside of marriage. Yet neither of these ideas relates to the concept of pornography.

We are not trying here to formulate a satisfactory definition of pornography. Our object is to make the following points clear:

An argument will be most fruitful if the participants first agree on what they are talking about.

One way to secure such agreement is to define the topic ostensively.

Choosing the right example, one that has all the central or typical characteristics, can make a topic not only clear but also vivid.

DEFINITION BY STIPULATION Arguments frequently involve matters of definition. In a discussion of gun control, for instance, you probably will hear one side speak of assault weapons and the other side speak instead of so-called assault weapons. In arguing, you can hope to get agreement — at least on what the topic of argument is — by offering a stipulative definition (from a Latin verb meaning “to bargain”). For instance, you and a representative of the other side can agree on a definition of assault weapon based on the meaning of the term in the ban approved by Congress in 1994, which expired in 2004, and which President Obama in 2013 asked Congress to renew. Although the renewal of the ban was unsuccessful, the definition was this: a semiautomatic firearm (the spent cartridge case is automatically extracted, and a new round is automatically reloaded into the chamber but isn’t fired until the trigger is pulled again) with a detachable magazine and at least two of the following five characteristics:

collapsible or folding stock

pistol grip (thus allowing the weapon to be fired from the hip)

bayonet mount

grenade launcher

flash suppressor (to keep the shooter from being blinded by muzzle flashes)

Again, this was the agreed-upon definition for the purposes of the legislation. Congress put fully automatic weapons into an entirely different category, and the legislatures of California and of New York each agreed on a stipulation different from that of Congress: In these two states, an assault weapon is defined as a semiautomatic firearm with a detachable magazine and with any one (not two) of the five bulleted items. The point is that for an argument to proceed rationally, and especially in the legal context, the key terms need to be precisely defined and agreed upon by all parties.

Let’s now look at stipulative definitions in other contexts. Who is a Native American? In discussing this issue, you might stipulate that Native American means any person with any Native American blood; or you might say, “For the purpose of the present discussion, I mean that a Native American is any person who has at least one grandparent of pure Native American blood.” A stipulative definition is appropriate in the following cases:

when no fixed or standard definition is available, and

when an arbitrary specification is necessary to fix the meaning of a key term in the argument.

Not everyone may accept your stipulative definition, and there will likely be defensible alternatives. In any case, when you stipulate a definition, your audience knows what you mean by the term.

It would not be reasonable to stipulate that by Native American you mean anyone with a deep interest in North American aborigines. That’s too idiosyncratic to be useful. Similarly, an essay on Jews in America will have to rely on a definition of the key idea. Perhaps the writer will stipulate the definition used in Israel: A Jew is a person who has a Jewish mother or, if not born of a Jewish mother, a person who has formally adopted the Jewish faith. Perhaps the writer will stipulate another meaning: Jews are people who consider themselves to be Jews. Some sort of reasonable definition must be offered.

To stipulate, however, that Jews means “persons who believe that the area formerly called Palestine rightfully belongs to the Jews” would hopelessly confuse matters. Remember the old riddle: If you call a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs does a dog have? The answer is four. Calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it a leg.

Later in this chapter you will see, in an essay titled “When ‘Identity Politics’ Is Rational,” that the author, Stanley Fish, begins by stipulating a definition. His first paragraph begins thus:

If there’s anything everyone is against in these election times, it’s “identity politics,” a phrase that covers a multitude of sins. Let me start with a definition. (It may not be yours, but it will at least allow the discussion to be framed.) You’re practicing identity politics when you vote for or against someone because of his or her skin color, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, or any other marker that leads you to say yes or no independently of a candidates’ ideas or policies.

Fish will argue in later paragraphs that sometimes identity politics makes very good sense, that it is not irrational, is not logically indefensible; but here we simply want to make two points — one about how a definition helps the writer, and one about how it helps the reader:

A definition is a good way to get started when drafting an essay, a useful stimulus (idea prompt, pattern, template, heuristic) that will help you to think about the issue, a device that will stimulate your further thinking.

A definition lets readers be certain that they understand what the author means by a crucial word.

Readers may disagree with Fish, but at least they know what he means when he speaks of identity politics.

A stipulation may be helpful and legitimate. Here’s the opening paragraph of a 1975 essay by Richard B. Brandt titled “The Morality and Rationality of Suicide.” Notice that the author does two things:

He first stipulates a definition.

Then, aware that the definition may strike some readers as too broad and therefore unreasonable or odd, he offers a reason on behalf of his definition.

“Suicide” is conveniently defined, for our purposes, as doing something which results in one’s death, either from the intention of ending one’s life or the intention to bring about some other state of affairs (such as relief from pain) which one thinks it certain or highly probable can be achieved only by means of death or will produce death. It may seem odd to classify an act of heroic self-sacrifice on the part of a soldier as suicide. It is simpler, however, not to try to define “suicide” so that an act of suicide is always irrational or immoral in some way; if we adopt a neutral definition like the above we can still proceed to ask when an act of suicide in that sense is rational, morally justifiable, and so on, so that all evaluations anyone might wish to make can still be made. (61)

Sometimes, a definition that at first seems extremely odd can be made acceptable by offering strong reasons in its support. Sometimes, in fact, an odd definition marks a great intellectual step forward. For instance, in 1990 the U.S. Supreme Court recognized that speech includes symbolic nonverbal expression such as protesting against a war by wearing armbands or by flying the American flag upside down. Such actions, because they express ideas or emotions, are now protected by the First Amendment. Few people today would disagree that speech should include symbolic gestures. (We include an example of controversy over this issue in Derek Bok’s essay “Protecting Freedom of Expression on the Campus” in Protecting Freedom of Expression on the Campus.)

A definition that seems notably eccentric to many readers and thus far has not gained much support is from Peter Singer’s Practical Ethics, in which the author suggests that a nonhuman being can be a person. He admits that “it sounds odd to call an animal a person” but says that it seems so only because of our habit of sharply separating ourselves from other species. For Singer, persons are “rational and self-conscious beings, aware of themselves as distinct entities with a past and a future.” Thus, although a newborn infant is a human being, it isn’t a person; however, an adult chimpanzee isn’t a human being but probably is a person. You don’t have to agree with Singer to know exactly what he means and where he stands. Moreover, if you read his essay, you may even find that his reasons are plausible and that by means of his unusual definition he has broadened your thinking.

THE IMPORTANCE OF DEFINITIONS Trying to decide on the best way to define a key idea or a central concept is often difficult as well as controversial. Death, for example, has been redefined in recent years. Traditionally, a person was considered dead when there was no longer any heartbeat. But with advancing medical technology, the medical profession has persuaded legislatures to redefine death as cessation of cerebral and cortical functions — so-called brain death.

Some scholars have hoped to bring clarity into the abortion debate by redefining life. Traditionally, human life has been seen as beginning at birth or perhaps at viability (the capacity of a fetus to live independently of the uterine environment). However, others have proposed a brain birth definition in the hope of resolving the abortion controversy. Some thinkers want abortion to be prohibited by law at the point where “integrated brain functioning begins to emerge,” allegedly about seventy days after conception. Whatever the merits of such a redefinition may be, the debate is convincing evidence of just how important the definition of certain terms can be.

LAST WORDS ABOUT DEFINITION Since Plato’s time in the fourth century B.C.E, it has often been argued that the best way to give a definition is to state the essence of the thing being defined. Thus, the classic example defines man as “a rational animal.” (Today, to avoid sexist implications, instead of man we would say human being or person.) That is, the property of rational animality is considered to be the essence of every human creature, so it must be mentioned in the definition of man. This statement guarantees that the definition is neither too broad nor too narrow. But philosophers have long criticized this alleged ideal type of definition on several grounds, one of which is that no one can propose such definitions without assuming that the thing being defined has an essence in the first place — an assumption that is not necessary. Thus, we may want to define causality, or explanation, or even definition itself, but it’s doubtful whether it is sound to assume that any of these concepts has an essence.

A much better way to provide a definition is to offer a set of sufficient and necessary conditions. Suppose we want to define the word circle and are conscious of the need to keep circles distinct from other geometric figures such as rectangles and spheres. We might express our definition by citing sufficient and necessary conditions as follows: “Anything is a circle if and only if it is a closed plane figure and all points on the circumference are equidistant from the center.” Using the connective “if and only if” (called the biconditional) between the definition and the term being defined helps to make the definition neither too exclusive (too narrow) nor too inclusive (too broad). Of course, for most ordinary purposes we don’t require such a formally precise definition. Nevertheless, perhaps the best criterion to keep in mind when assessing a proposed definition is whether it can be stated in the “if and only if” form, and whether, if so stated, it is true; that is, if it truly specifies all and only the things covered by the word being defined. The Thinking Critically exercise that follows provides examples.

We aren’t saying that the four sentences in the table below are incontestable. In fact, they are definitely arguable. We offer them merely to show ways of defining, and the act of defining is one way of helping to get your own thoughts going. Notice, too, that the fourth example, a “statement of necessary and sufficient conditions” (indicated by if and only if), is a bit stiff for ordinary writing. An informal prompt along this line might begin, “Essentially, something can be called pornography if it presents….”

THINKING CRITICALLY Giving Definitions

In the spaces provided, define one of the “new terms” provided according to the definition type stipulated.

| DEFINITION TYPE | EXAMPLE | NEW TERM | YOUR DEFINITION |

| Synonym | “Pornography, simply stated, is obscenity.” |

Police brutality Helicopter parenting Alternative music Organic foods | |

| Example | “Pornography can be seen, for example, in D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, in the scene where …” |

Police brutality Helicopter parenting Alternative music Organic foods |

|

| Stipulation | “For the purposes of this essay, pornography means any type of media that …” |

Police brutality Helicopter parenting Alternative music Organic foods |

|

| Statement of necessary and sufficient conditions | “Something can be called pornography if and only if it presents sexually stimulating material without offering anything of redeeming social value.” |

Police brutality Helicopter parenting Alternative music Organic foods |

To complete this activity online, click here.

To complete this activity online, click here.

ASSUMPTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed the assumptions made by the authors of two essays on religious freedoms. But we have more to say about assumptions. We’ve already said that in the form of discourse known as argument, certain statements are offered as reasons for other statements. But even the longest and most complex chain of reasoning or proof is fastened to assumptions — one or more unexamined beliefs. (Even if writer and reader share such a belief, it is no less an assumption.) Benjamin Franklin argued against paying salaries to the holders of executive offices in the federal government on the grounds that men are moved by ambition (love of power) and by avarice (love of money) and that powerful positions conferring wealth incite men to do their worst. These assumptions he stated, although he felt no need to argue them at length because he assumed that his readers shared them.

An assumption may be unstated. A writer, painstakingly arguing specific points, may choose to keep one or more of the argument’s assumptions tacit. Or the writer may be completely unaware of an underlying assumption. For example, Franklin didn’t even bother to state another assumption. He must have assumed that persons of wealth who accept an unpaying job (after all, only persons of wealth could afford to hold unpaid government jobs) will have at heart the interests of all classes of people, not only the interests of their own class. Probably Franklin didn’t state this assumption because he thought it was perfectly obvious, but if you think critically about it, you may find reasons to doubt it. Surely one reason we pay our legislators is to ensure that the legislature does not consist only of people whose incomes may give them an inadequate view of the needs of others.

As another example, here are two assumptions in the argument for permitting abortion:

Ours is a pluralistic society, in which we believe that the religious beliefs of one group should not be imposed on others.

Personal privacy is a right, and a woman’s body is hers, not to be violated by laws that forbid her from doing certain things to her body.

But these (and other) arguments assume that a fetus is not — or not yet — a person and therefore is not entitled to the same protection against assaults that we are. Virtually all of us assume that it is usually wrong to kill a human being. Granted, there may be instances in which we believe it’s acceptable to take a human life, such as self-defense against a would-be murderer. But even here we find a shared assumption that persons are ordinarily entitled not to be killed.

The argument about abortion, then, usually depends on opposed assumptions. For one group, the fetus is a human being and a potential person — and this potentiality is decisive. For the other group, it is not. Persons arguing one side or the other of the abortion issue ought to be aware that opponents may not share their assumptions.

PREMISES AND SYLLOGISMS

Premises are stated assumptions that are used as reasons in an argument. (The word comes from a Latin word meaning “to send before” or “to set in front.”) A premise thus is a statement set down — assumed — before the argument begins. The joining of two premises — two statements taken to be true — to produce a conclusion, a third statement, is a syllogism (from the Greek for “a reckoning together”). The classic example is this:

| Major premise: | All human beings are mortal. |

| Minor premise: | Socrates is a human being. |

| Conclusion: | Socrates is mortal. |

DEDUCTION

The mental process of moving from one statement (“All human beings are mortal”) through another (“Socrates is a human being”) to yet a further statement (“Socrates is mortal”) is deduction, from the Latin for “lead down from.” In this sense, deductive reasoning doesn’t give us any new knowledge, although it’s easy to construct examples that have so many premises, or premises that are so complex, that the conclusion really does come as news to most who examine the argument. Thus, the great fictional detective Sherlock Holmes was credited by his admiring colleague, Dr. Watson, with having unusual powers of deduction. Watson meant in part that Holmes could see the logical consequences of apparently disconnected reasons, the number and complexity of which left others at a loss. What is common in all cases of deduction is that the reasons or premises offered are supposed to contain within themselves, so to speak, the conclusion extracted from them.

Often a syllogism is abbreviated. Martin Luther King Jr., defending a protest march, wrote in “Letter from Birmingham Jail”:

You assert that our actions, even though peaceful, must be condemned because they precipitate violence.

Fully expressed, the argument that King attributes to his critics would be stated thus:

Society must condemn actions (even if peaceful) that precipitate violence.

This action (though peaceful) will precipitate violence.

Therefore, society must condemn this action.

An incomplete or abbreviated syllogism in which one of the premises is left unstated, of the sort found in King’s original quotation, is an enthymeme (from the Greek for “in the mind”).

Here is another, more whimsical example of an enthymeme, in which both a premise and the conclusion are left implicit. Henry David Thoreau remarked that “circumstantial evidence can be very strong, as when you find a trout in the milk.” The joke, perhaps intelligible only to people born before 1930 or so, depends on the fact that milk used to be sold “in bulk” — that is, ladled out of a big can directly to the customer by the farmer or grocer. This practice was prohibited in the 1930s because for centuries the sellers, seeking to increase their profit, were diluting the milk with water. Thoreau’s enthymeme can be fully expressed thus:

Trout live only in water.

This milk has a trout in it.

Therefore, this milk has water in it.

These enthymemes have three important properties: Their premises are true, the form of their argument is valid, and they leave implicit either the conclusion or one of the premises.

SOUND ARGUMENTS

The purpose of a syllogism is to present reasons that establish its conclusion. This is done by making sure that the argument satisfies both of two independent criteria:

First, all of the premises must be true.

Second, the syllogism must be valid.

Once these criteria are satisfied, the conclusion of the syllogism is guaranteed. Any such argument is said to establish or to prove its conclusion — to use another term, it is said to be sound. Here’s an example of a sound argument, a syllogism that proves its conclusion:

Extracting oil from the Arctic Wildlife Refuge would adversely affect the local ecology.

Adversely affecting the local ecology is undesirable, unless there is no better alternative fuel source.

Therefore, extracting oil from the Arctic Wildlife Refuge is undesirable, unless there is no better alternative fuel source.

Each premise is true, and the syllogism is valid, so it establishes its conclusion.

But how do we tell in any given case that an argument is sound? We perform two different tests, one for the truth of each of the premises and another for the validity of the argument.

The basic test for the truth of a premise is to determine whether what it asserts corresponds with reality; if it does, then it is true, and if it doesn’t, then it is false. Everything depends on the premise’s content — what it asserts — and the evidence for it. (In the preceding syllogism, it’s possible to test the truth of the premises by checking the views of experts and interested parties, such as policymakers, environmental groups, and experts on energy.)

The test for validity is quite different. We define a valid argument as one in which the conclusion follows from the premises, so that if all the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true, too. The general test for validity, then, is this: If one grants the premises, one must also grant the conclusion. In other words, if one grants the premises but denies the conclusion, is one caught in a self-contradiction? If so, the argument is valid; if not, the argument is invalid.

The preceding syllogism passes this test. If you grant the information given in the premises but deny the conclusion, you contradict yourself. Even if the information were in error, the conclusion in this syllogism would still follow from the premises — the hallmark of a valid argument! The conclusion follows because the validity of an argument is a purely formal matter concerning the relation between premises and conclusion based on what they mean.

It’s possible to see this relationship more clearly by examining an argument that is valid but that, because one or both of the premises are false, does not establish its conclusion. Here’s an example of such a syllogism:

The whale is a large fish.

All large fish have scales.

Therefore, whales have scales.

We know that the premises and the conclusion are false: Whales are mammals, not fish, and not all large fish have scales (sharks have no scales, for instance). But in determining the argument’s validity, the truth of the premises and the conclusion is beside the point. Just a little reflection assures us that if both premises were true, then the conclusion would have to be true as well. That is, anyone who grants the premises of this syllogism yet denies the conclusion contradicts herself. So the validity of an argument does not in any way depend on the truth of the premises or the conclusion.

A sound argument, as we said, is one that passes both the test of true premises and the test of valid inference. To put it another way, a sound argument does the following:

It passes the test of content (the premises are true, as a matter of fact).

It passes the test of form (its premises and conclusion, by virtue of their very meanings, are so related that it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false).

Accordingly, an unsound argument, one that fails to prove its conclusion, suffers from one or both of two defects:

Not all the premises are true.

The argument is invalid.

Usually, we have in mind one or both defects when objecting to someone’s argument as “illogical.” In evaluating a deductive argument, therefore, you must always ask: Is it vulnerable to criticism on the grounds that one (or more) of its premises is false? Or is the inference itself vulnerable because even if all the premises are true, the conclusion still wouldn’t follow?

A deductive argument proves its conclusion if and only if two conditions are satisfied: (1) All the premises are true, and (2) it would be inconsistent to assert the premises and deny the conclusions.

A WORD ABOUT FALSE PREMISES Suppose that one or more of a syllogism’s premises are false but the syllogism itself is valid. What does that indicate about the truth of the conclusion? Consider this example:

All Americans prefer vanilla ice cream to other flavors.

Jimmy Fallon is an American.

Therefore, Jimmy Fallon prefers vanilla ice cream to other flavors.

The first (or major) premise in this syllogism is false. Yet the argument passes our formal test for validity; if one grants both premises, then one must accept the conclusion. So we can say that the conclusion follows from its premises, even though the premises do not prove the conclusion. This is not as paradoxical as it may sound. For all we know, the argument’s conclusion may in fact be true; Jimmy Fallon may indeed prefer vanilla ice cream, and the odds are that he does because consumption statistics show that a majority of Americans prefer vanilla. Nevertheless, if the conclusion in this syllogism is true, it’s not because this argument proved it.

A WORD ABOUT INVALID SYLLOGISMS Usually, one can detect a false premise in an argument, especially when the suspect premise appears in someone else’s argument. A trickier business is the invalid syllogism. Consider this argument:

All terrorists seek publicity for their violent acts.

John Doe seeks publicity for his violent acts.

Therefore, John Doe is a terrorist.

In this syllogism, let’s grant that the first (major) premise is true. Let’s also grant that the conclusion may well be true. Finally, the person mentioned in the second (minor) premise could indeed be a terrorist. But it’s also possible that the conclusion is false; terrorists aren’t the only ones who seek publicity for their violent acts — consider, for example, the violence committed against doctors, clinic workers, and patients at clinics where abortions are performed. In short, the truth of the two premises is no guarantee that the conclusion is also true. It’s possible to assert both premises and deny the conclusion without being self-contradictory.

How do we tell, in general and in particular cases, whether a syllogism is valid? Chemists use litmus paper to determine instantly whether the liquid in a test tube is an acid or a base. Unfortunately, logic has no litmus test to tell us instantly whether an argument is valid or invalid. Logicians beginning with Aristotle have developed techniques to test any given argument, no matter how complex or subtle, to determine its validity. But the results of their labors cannot be expressed in a paragraph or even a few pages; this is why entire semester-long courses are devoted to teaching formal deductive logic. Apart from advising you to consult Chapter 9, A Logician’s View: Deduction, Induction, Fallacies, all we can do here is repeat two basic points.

First, the validity of deductive arguments is a matter of their form or structure. Even syllogisms like the one on the Arctic Wildlife Refuge above come in a large variety of forms (256 forms, to be precise), and only some of these forms are valid. Second, all valid deductive arguments (and only such arguments) pass this test: If one accepts all the premises, then one must accept the conclusion as well. Hence, if it’s possible to accept the premises but reject the conclusion (without self-contradiction, of course), then the argument is invalid.

Let’s exit from further discussion of this important but difficult subject on a lighter note. Many illogical arguments masquerade as logical. Consider this example: If it takes a horse and carriage four hours to go from Pinsk to Chelm, does it follow that a carriage with two horses will get there in two hours?

Note: In Chapter 9, we discuss at some length other kinds of deductive arguments, as well as fallacies, which are kinds of invalid reasoning.

INDUCTION

Whereas deduction takes beliefs and assumptions and extracts their hidden consequences, induction uses information about observed cases to reach a conclusion about unobserved cases. (The word comes from the Latin in ducere, “to lead into” or “to lead up to.”) If we observe that the bite of a certain snake is poisonous, we may conclude on the basis of this evidence that the bite of another snake of the same general type is also poisonous. Our inference might be even broader: If we observe that snake after snake of a certain type has a poisonous bite and that these snakes are all rattlesnakes, then we’re tempted to generalize that all rattlesnakes are poisonous.

By far the most common way to test the adequacy of a generalization is to consider one or more counterexamples. If the counterexamples are genuine and reliable, then the generalization must be false. For example, Ronald Takaki’s essay on the “myth” of Asian racial superiority is full of examples that contradict the alleged superiority of Asians; they are counterexamples to that thesis, and they help to expose it as a “myth.” What is true of Takaki’s reasoning is true generally in argumentative writing: We constantly test our generalizations by considering them against actual or possible counterexamples, or by doing research on the issue.

Unlike deduction, induction yields conclusions that go beyond the information contained in the premises used in their support. It’s not surprising that the conclusions of inductive reasoning are not always true, even when all the premises are true. On page 83, we gave as an example our observation that on previous days a subway has run at 6:00 A.M. and that therefore we conclude that it runs at 6:00 A.M. every day. Suppose, following this reasoning, we arrive at the subway platform just before 6:00 A.M. on a given day and wait for an hour without seeing a single train. What inference should we draw to explain this? Possibly today is Sunday, and the subway doesn’t run before 7:00 A.M. Or possibly there was a breakdown earlier this morning. Whatever the explanation might be, we relied on a sample that wasn’t large enough (a larger sample might have included some early morning breakdowns) or representative enough (a more representative sample would have included the later starts on Sundays and holidays).

A WORD ABOUT SAMPLES When we reason inductively, much depends on the size and the quality of the sample (we say “sample” because a writer probably cannot examine every instance). If, for example, we’re offering an argument concerning the politics of members of sororities and fraternities, we probably cannot interview every member. Rather, we select a sample. But is the sample a fair one? Is it representative of the larger group? We may interview five members of Alpha Tau Omega and find that all five are Republicans, yet we cannot legitimately conclude that all members of ATO are Republicans. The problem doesn’t always involve failing to interview an adequately large sample group. For example, a poll of ten thousand college students tells us very little about “college students” if all ten thousand are white males at the University of Texas. Because such a sample leaves out women and minority males, it isn’t sufficiently representative of “college students” as a group. Further, though not all students at the University of Texas are from Texas or even from the Southwest, it’s quite likely that the student body is not fully representative (e.g., in race and in income) of American college students. If this conjecture is correct, even a truly representative sample of University of Texas students wouldn’t enable us to draw firm conclusions about American college students.

In short: An argument that uses samples ought to tell the reader how the samples were chosen. If it doesn’t provide this information, the reader should treat the argument with suspicion.

EVIDENCE: EXPERIMENTATION, EXAMPLES, AUTHORITATIVE TESTIMONY, STATISTICS

Different disciplines use different kinds of evidence:

In literary studies, the texts are usually the chief evidence.

In the social sciences, field research (interviews, surveys) usually provides evidence.

In the sciences, reports of experiments are the usual evidence; if an assertion cannot be tested — if one cannot show it to be false — it is a belief, an opinion, not a scientific hypothesis.

EXPERIMENTATION Induction is obviously useful in arguing. If, for example, one is arguing that handguns should be controlled, one will point to specific cases in which handguns caused accidents or were used to commit crimes. In arguing that abortion has a traumatic effect on women, one will point to women who testify to that effect. Each instance constitutes evidence for the relevant generalization.

In a courtroom, evidence bearing on the guilt of the accused is introduced by the prosecution, and evidence to the contrary is introduced by the defense. Not all evidence is admissible (e.g., hearsay is not, even if it’s true), and the law of evidence is a highly developed subject in jurisprudence. In the forum of daily life, the sources of evidence are less disciplined. Daily experience, a particularly memorable observation, an unusual event — any or all of these may serve as evidence for (or against) some belief, theory, hypothesis, or explanation. Science involves the systematic study of what experience can yield, and one of the most distinctive features of the evidence that scientists can marshal on behalf of their claims is that it is the result of experimentation. Experiments are deliberately contrived situations, often complex in their technology, that are designed to yield particular observations. What the ordinary person does with unaided eye and ear, the scientist does, much more carefully and thoroughly, with the help of laboratory instruments.

The variety, extent, and reliability of the evidence obtained in daily life are quite different from those obtained in the laboratory. It’s no surprise that society attaches much more weight to the “findings” of scientists than to the corroborative (much less the contrary) experiences of ordinary people. No one today would seriously argue that the sun really does go around the earth just because it looks that way; nor would we argue that because viruses are invisible to the naked eye they cannot cause symptoms such as swellings and fevers, which are plainly evident.

EXAMPLES One form of evidence is the example. Suppose we argue that a candidate is untrustworthy and shouldn’t be elected to public office. We point to episodes in his career — his misuse of funds in 2008 and the false charges he made against an opponent in 2016 — as examples of his untrustworthiness. Or if we’re arguing that President Truman ordered the atom bomb dropped to save American (and, for that matter, Japanese) lives that otherwise would have been lost in a hard-fought invasion of Japan, we point to the stubbornness of the Japanese defenders in battles on the islands of Saipan, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa, where Japanese soldiers fought to the death rather than surrender.

These examples, we say, indicate that the Japanese defenders of the main islands would have fought to their deaths without surrendering, even though they knew defeat was certain. Or if we argue that the war was nearly won when Truman dropped the bomb, we can cite secret peace feelers as examples of the Japanese willingness to end the war.

An example is a sample. These two words come from the same Old French word, essample, from the Latin exemplum, which means “something taken out” — that is, a selection from the group. A Yiddish proverb shrewdly says, “‘For example’ is no proof,” but the evidence of well-chosen examples can go a long way toward helping a writer to convince an audience.

In arguments, three sorts of examples are especially common:

real events

invented instances (artificial or hypothetical cases)

analogies

We will treat each of these briefly.

Real Events In referring to Truman’s decision to drop the atom bomb, we’ve already touched on examples drawn from real events — the battles at Saipan and elsewhere. And we’ve also seen Ben Franklin pointing to an allegedly real happening, a fish that had consumed a smaller fish. The advantage of an example drawn from real life, whether a great historical event or a local incident, is that its reality gives it weight. It cannot simply be brushed off.

Yet an example drawn from reality may not be as clear-cut as we would like. Suppose, for instance, that someone cites the Japanese army’s behavior on Saipan and on Iwo Jima as evidence that the Japanese later would have fought to the death in an American invasion of Japan and would therefore have inflicted terrible losses on themselves and on the Americans. This example is open to the response that in June and July 1945 certain Japanese diplomats sent out secret peace feelers, so that in August 1945, when Truman authorized dropping the bomb, the situation was very different.

Similarly, in support of the argument that nations will no longer resort to using atomic weapons, some people have offered as evidence the fact that since World War I the great powers have not used poison gas. But the argument needs more support than this fact provides. Poison gas wasn’t decisive or even highly effective in World War I. Moreover, the invention of gas masks made its use obsolete.

In short, any real event is so entangled in historical circumstances that it might not be adequate or relevant evidence in the case being argued. In using a real event as an example (a perfectly valid strategy), the writer must demonstrate that the event can be taken out of its historical context for use in the new context of argument. Thus, in an argument against using atomic weapons in warfare, the many deaths and horrible injuries inflicted on the Japanese at Hiroshima and Nagasaki can be cited as effects of nuclear weapons that would invariably occur and did not depend on any special circumstances of their use in Japan in 1945.

Invented Instances Artificial or hypothetical cases — invented instances — have the great advantage of being protected from objections of the sort we have just given. Recall Thoreau’s trout in the milk; that was a colorful hypothetical case that illustrated his point well. An invented instance (“Let’s assume that a burglar promises not to shoot a householder if the householder swears not to identify him. Is the householder bound by the oath?”) is something like a drawing of a flower in a botany textbook or a diagram of the folds of a mountain in a geology textbook. It is admittedly false, but by virtue of its simplifications it sets forth the relevant details very clearly. Thus, in a discussion of rights, the philosopher Charles Frankel says:

Strictly speaking, when we assert a right for X, we assert that Y has a duty. Strictly speaking, that Y has such a duty presupposes that Y has the capacity to perform this duty. It would be nonsense to say, for example, that a nonswimmer has a moral duty to swim to the help of a drowning man.

This invented example is admirably clear, and it is immune to charges that might muddy the issue if Frankel, instead of referring to a wholly abstract person, Y, talked about some real person, Jones, who did not rescue a drowning man. For then Frankel would get bogged down over arguing about whether Jones really couldn’t swim well enough to help, and so on.

Yet invented examples have drawbacks. First and foremost, they cannot serve as evidence. A purely hypothetical example can illustrate a point or provoke reconsideration of a generalization, but it cannot substitute for actual events as evidence supporting an inductive inference. Sometimes, such examples are so fanciful that they fail to convince the reader. Thus, the philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson, in the course of an argument entitled “A Defense of Abortion,” asks the reader to imagine waking up one day and finding that against her will a celebrated violinist whose body is not adequately functioning has been hooked up into her body for life support. Does she have the right to unplug the violinist? As you read the essays we present in this textbook, you’ll have to decide for yourself whether the invented cases proposed by various authors are helpful or whether they are so remote that they hinder thought. Readers will have to decide, too, about when they can use invented cases to advance their own arguments.

But we add one point: Even a highly fanciful invented case can have the valuable effect of forcing us to see where we stand. A person may say that she is, in all circumstances, against vivisection — the practice of performing operations on live animals for the purpose of research. But what would she say if she thought that an experiment on one mouse would save the life of someone she loves? Conversely, if she approves of vivisection, would she also approve of sacrificing the last giant panda to save the life of a senile stranger, a person who in any case probably wouldn’t live longer than another year? Artificial cases of this sort can help us to see that we didn’t really mean to say such-and-such when we said so-and-so.

Analogies The third sort of example, analogy, is a kind of comparison. An analogy asserts that things that are alike in some ways are alike in yet another way as well. Here’s an example:

Before the Roman Empire declined as a world power, it exhibited a decline in morals and in physical stamina; our society today shows a decline in both morals (consider the high divorce rate and the crime rate) and physical culture (consider obesity in children). America, like Rome, will decline as a world power.

Strictly speaking, an analogy is an extended comparison in which different things are shown to be similar in several ways. Thus, if one wants to argue that a head of state should have extraordinary power during wartime, one can argue that the state at such a time is like a ship in a storm: The crew is needed to lend its help, but the decisions are best left to the captain. (Notice that an analogy compares things that are relatively unlike. Comparing the plight of one ship to another or of one government to another isn’t an analogy; it’s an inductive inference from one case of the same sort to another such case.)

Let’s consider another analogy. We have already glanced at Judith Thomson’s hypothetical case in which the reader wakes up to find herself hooked up to a violinist in need of life support. Thomson uses this situation as an analogy in an argument about abortion. The reader stands for the mother; the violinist, for the unwanted fetus. You may want to think about whether this analogy is close enough to pregnancy to help illuminate your own thinking about abortion.

The problem with argument by analogy is this: Two admittedly different things are agreed to be similar in several ways, and the arguer goes on to assert or imply that they are also similar in another way — the point being argued. (That’s why Thomson argues that if something is true of the reader-hooked-up-to-a-violinist, it is also true of the pregnant-mother-hooked-up-to-a-fetus.) But the two things that are said to be analogous and that are indeed similar in characteristics A, B, and C are also different — let’s say in characteristics D and E. As Bishop Butler is said to have remarked in the early eighteenth century, “Everything is what it is, and not another thing.”

Analogies can be convincing, especially because they can make complex issues seem simple. “Don’t change horses in midstream” isn’t a statement about riding horses across a river but, rather, about choosing new leaders in critical times. Still, in the end, analogies don’t necessarily prove anything. What may be true about riding horses across a stream may not be true about choosing new leaders in troubled times. Riding horses across a stream and choosing new leaders are fundamentally different things, and however much they may be said to resemble each other, they remain different. What is true for one need not be true for the other.

Analogies can be helpful in developing our thoughts and in helping listeners or readers to understand a point we’re trying to make. It is sometimes argued, for instance — on the analogy of the doctor–patient, the lawyer–client, or the priest–penitent relationship — that newspaper and television reporters should not be required to reveal their confidential sources. That is worth thinking about: Do the similarities run deep enough, or are there fundamental differences? Consider another example: Some writers who support abortion argue that the fetus is not a person any more than the acorn is an oak. That is also worth thinking about. But one should also think about this response: A fetus is not a person, just as an acorn is not an oak; but an acorn is a potential oak, and a fetus is a potential person, a potential adult human being. Children, even newborn infants, have rights, and one way to explain this claim is to call attention to their potentiality to become mature adults. Thus, some people argue that the fetus, by analogy, has the rights of an infant, for the fetus, like the infant, is a potential adult.

Three analogies for consideration: First, let’s examine a brief comparison made by Jill Knight, a member of the British Parliament, speaking about abortion:

Babies are not like bad teeth, to be jerked out because they cause suffering.

Her point is effectively put; it remains for the reader to decide whether fetuses are babies and if a fetus is not a baby, why it can or cannot be treated like a bad tooth.

Now a second bit of analogical reasoning, again about abortion: Thomas Sowell, an economist at the Hoover Institute, grants that women have a legal right to abortion, but he objects to a requirement that the government pay for abortions:

Because the courts have ruled that women have a legal right to an abortion, some people have jumped to the conclusion that the government has to pay for it. You have a constitutional right to privacy, but the government has no obligation to pay for your window shades. (Pink and Brown People, 1981, p. 57)

We leave it to you to decide whether the analogy is compelling — that is, if the points of resemblance are sufficiently significant to allow you to conclude that what’s true of people wanting window shades should be true of people wanting abortions.

And one more: A common argument on behalf of legalizing gay marriage drew an analogy between gay marriage and interracial marriage, a practice that was banned in sixteen states until 1967, when the Supreme Court declared miscegenation statutes unconstitutional. The gist of the analogy was this: Racism and discrimination against gay and lesbian people are the same. If marriage is a fundamental right — as the Supreme Court held in its 1967 decision striking down bans on miscegenation — then it is a fundamental right for gay and lesbian people as well as heterosexual people.

AUTHORITATIVE TESTIMONY Another form of evidence is testimony, the citation or quotation of authorities. In daily life, we rely heavily on authorities of all sorts: We get a doctor’s opinion about our health, we read a book because an intelligent friend recommends it, we see a movie because a critic gave it a good review, and we pay at least a little attention to the weather forecaster.

In setting forth an argument, one often tries to show that one’s view is supported by notable figures — perhaps Jefferson, Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., or scientists who won the Nobel Prize. You may recall that in Chapter 2, in talking about medical marijuana legalization, we presented an essay by Sanjay Gupta. To make certain that you were impressed by his ideas, we described him as CNN’s chief medical correspondent and a leading public health expert. In our Chapter 2 discussion of Sally Mann, we qualified our description of her controversial photographs by noting that Time magazine called her “America’s Best Photographer” and the New Republic called her book “one of the great photograph books of our time.” But heed some words of caution:

Be sure that the authority, however notable, is an authority on the topic in question. (A well-known biologist might be an authority on vitamins but not on the justice of war.)

Be sure that the authority is unbiased. (A chemist employed by the tobacco industry isn’t likely to admit that smoking may be harmful, and a producer of violent video games isn’t likely to admit that playing those games stimulates violence.)

Beware of nameless authorities: “a thousand doctors,” “leading educators,” “researchers at a major medical school.” (If possible, offer at least one specific name.)

Be careful when using authorities who indeed were great authorities in their day but who now may be out of date. (Examples would include Adam Smith on economics, Julius Caesar on the art of war, Louis Pasteur on medicine).

Cite authorities whose opinions your readers will value. (William F. Buckley Jr.’s conservative/libertarian opinions mean a good deal to readers of the magazine that he founded, the National Review, but probably not to most liberal thinkers. Gloria Steinem’s liberal/feminist opinions carry weight with readers of the magazines that she cofounded, New York and Ms. magazine, but probably not with most conservative thinkers.) When writing for the general reader — your usual audience — cite authorities whom the general reader is likely to accept.

One other point: You may be an authority. You probably aren’t nationally known, but on some topics you might have the authority of personal experience. You may have been injured on a motorcycle while riding without wearing a helmet, or you may have escaped injury because you wore a helmet. You may have dropped out of school and then returned. You may have tutored a student whose native language isn’t English, you may be such a student who has received tutoring, or you may have attended a school with a bilingual education program. In short, your personal testimony on topics relating to these issues may be invaluable, and a reader will probably consider it seriously.

STATISTICS The last sort of evidence we discuss here is quantitative, or statistical. The maxim “More is better” captures a basic idea of quantitative evidence: Because we know that 90 percent is greater than 75 percent, we’re usually ready to grant that any claim supported by experience in 90 percent of cases is more likely to be true than an alternative claim supported by experience in only 75 percent of cases. The greater the difference, the greater our confidence. Consider an example. Honors at graduation from college are often computed on the basis of a student’s cumulative grade-point average (GPA). The undisputed assumption is that the nearer a student’s GPA is to a perfect record (4.0), the better scholar he or she is and therefore the more deserving of highest honors. Consequently, a student with a GPA of 3.9 at the end of her senior year is a stronger candidate for graduating summa cum laude than another student with a GPA of 3.6. When faculty members on the honors committee argue over the relative academic merits of graduating seniors, we know that these quantitative, statistical differences in student GPAs will be the basic (if not the only) kind of evidence under discussion.

Graphs, Tables, Numbers Statistical information can be presented in many forms, but it tends to fall into two main types: the graphic and the numerical. Graphs, tables, and pie charts are familiar ways of presenting quantitative data in an eye-catching manner. (See Visuals as Aids to Clarity: Maps, Graphs, and Pie Charts.) To prepare the graphics, however, one first has to decide how best to organize and interpret the numbers, and for some purposes it may be more appropriate to directly present the numbers themselves.

But is it better to present the numbers in percentages or in fractions? Should a report say that the federal budget (1) underwent a twofold increase over the decade; (2) increased by 100 percent; (3) doubled; or (4) at the beginning of the decade was one-half what it was at the end? These are equivalent ways of saying the same thing. Making a choice among them, therefore, will likely rest on whether one’s aim is to dramatize the increase (a 100 percent increase looks larger than a doubling) or to play down its size.

Thinking about Statistical Evidence Statistics often get a bad name because it’s so easy to misuse them (unintentionally or not) and so difficult to be sure that they were gathered correctly in the first place. (One old saying goes, “There are lies, damned lies, and statistics.”) Every branch of social science and natural science needs statistical information, and countless decisions in public and private life are based on quantitative data in statistical form. It’s important, therefore, to be sensitive to the sources and reliability of the statistics and to develop a healthy skepticism when you confront statistics whose parentage is not fully explained.

Consider statistics that pop up in conversations about wealth distribution in the United States. In 2014, the Census Bureau calculated that the median household income in the United States was $53,657, meaning that half of households earned less than this amount and half earned above it. However, the average — technically, the mean — household income in the same year was $72,641, about $19,000 (or 39 percent) higher. Which number more accurately represents the typical household income? Both are “correct,” but both are calculated with different measures, median and mean. If a politician wanted to argue that the United States has a strong middle class, he might use the average (mean) income as evidence, a number calculated by dividing the total income of all households by the total number of households. If another politician wished to make a rebuttal, she could point out that the average income paints a rosy picture because the wealthiest households skew the average higher. The median income (representing the number above and below which two halves of all households fall) should be the measure we use, the rebutting politician could argue, because it helps reduce the effect of the limitless ceiling of higher incomes and the finite floor of lower incomes at zero.

A CHECKLIST FOR EVALUATING STATISTICAL EVIDENCE

Regard statistical evidence (like all other evidence) cautiously, and don’t accept it until you have thought about these questions:

Was it compiled by a disinterested (impartial) source? The source’s name doesn’t always reveal its particular angle (e.g., People for the American Way), but sometimes it lets you know what to expect (e.g., National Rifle Association, American Civil Liberties Union).

Is it based on an adequate sample?

Is the statistical evidence recent enough to be relevant?

How many of the factors likely to be relevant were identified and measured?

Are the figures open to a different and equally plausible interpretation?

If a percentage is cited, is it the average (or mean), or is it the median?

We are not suggesting that everyone who uses statistics is trying to deceive or is unconsciously being deceived by them. We suggest only that statistics are open to widely different interpretations and that often those columns of numbers, which appear to be so precise with their decimal points, may actually be imprecise and possibly worthless if they’re based on insufficient or biased samples.

Consider the following statistics: Suppose in a given city in 2014, 1 percent of the victims in fatal automobile accidents were bicyclists. In the same city in 2015, the percentage of bicyclists killed in automobile accidents was 2 percent. Was the increase 1 percent (not an alarming figure), or was it 100 percent (a staggering figure)? The answer is both, depending on whether we’re comparing (1) bicycle deaths in automobile accidents with all deaths in automobile accidents (that’s an increase of 1 percent), or (2) bicycle deaths in automobile accidents only with other bicycle deaths in automobile accidents (an increase of 100 percent). An honest statement would say that bicycle deaths due to automobile accidents doubled in 2015, increasing from 1 to 2 percent. But here’s another point: Although every such death is lamentable, if there was one such death in 2014 and two in 2015, the increase from one death to two (an increase of 100 percent!) hardly suggests a growing problem that needs attention. No one would be surprised to learn that in the next year there were no deaths at all, or only one or two.

If it’s sometimes difficult to interpret statistics, it’s often at least equally difficult to establish accurate statistics. Consider this example:

Advertisements are the most prevalent and toxic of the mental pollutants. From the moment your radio alarm sounds in the morning to the wee hours of late-night TV, microjolts of commercial pollution flood into your brain at the rate of about three thousand marketing messages per day. (Kalle Lasn, Culture Jam [1999], 18–19)

Lasn’s book includes endnotes as documentation, so, being curious about the statistics, we turn to the appropriate page and find this information concerning the source of his data:

“three thousand marketing messages per day.” Mark Landler, Walecia Konrad, Zachary Schiller, and Lois Therrien, “What Happened to Advertising?” BusinessWeek, September 23, 1991, page 66. Leslie Savan in The Sponsored Life (Temple University Press, 1994), page 1, estimated that “16,000 ads flicker across an individual’s consciousness daily.” I did an informal survey in March 1995 and found the number to be closer to 1,500 (this included all marketing messages, corporate images, logos, ads, brand names, on TV, radio, billboards, buildings, signs, clothing, appliances, in cyberspace, etc., over a typical twenty-four hour period in my life). (219)

Well, this endnote is odd. In the earlier passage, the author asserted that about “three thousand marketing messages per day” flood into a person’s brain. In the documentation, he cites a source for that statistic from BusinessWeek — though we haven’t the faintest idea how the authors of the BusinessWeek article came up with that figure. Oddly, he goes on to offer a very different figure (16,000 ads) and then, to our confusion, offers yet a third figure, 1,500, based on his own “informal survey.”

Probably the one thing we can safely say about all three figures is that none of them means very much. Even if the compilers of the statistics explained exactly how they counted — let’s say that among countless other criteria they assumed that the average person reads one magazine per day and that the average magazine contains 124 advertisements — it would be hard to take them seriously. After all, in leafing through a magazine, some people may read many ads and some may read none. Some people may read some ads carefully — but perhaps just to enjoy their absurdity. Our point: Although the author in his text said, without implying any uncertainty, that “about three thousand marketing messages per day” reach an individual, it’s evident (by checking the endnote) that even he is confused about the figure he gives.

Unreliable Statistics We’d like to make a final point about the unreliability of some statistical information — data that looks impressive but that is, in fact, insubstantial. For instance, Marilyn Jager Adams studied the number of hours that families read to their children in the five or so years before the children start attending school. In her book Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning about Print (1994), she pointed out that in all those preschool years, poor families read to their children only 25 hours, whereas in the same period middle-income families read 1,000 to 1,700 hours. The figures were much quoted in newspapers and by children’s advocacy groups. Adams could not, of course, interview every family in these two groups; she had to rely on samples. What were her samples? For poor families, she selected 24 children in 20 families, all in Southern California. Ask yourself: Can families from only one geographic area provide an adequate sample for a topic such as this? Moreover, let’s think about Adams’s sample of middle-class families. How many families constituted that sample? Exactly one — her own. We leave it to you to judge the validity of her findings.

Quiz

What is wrong with the following statistical proof that children do not have time for school?

One-third of the time they are sleeping (about 122 days).

One-eighth of the time they are eating (three hours a day, totaling 45 days).

One-fourth of the time they are on summer and other vacations (91 days).

Two-sevenths of the year is weekends (104 days).

Total: 362 days — so how can a kid have time for school?