8.1 Puberty

Compare photos of yourself from late elementary school and high school to get a vivid sense of the changes that occur during puberty. From the size of our thighs to the shape of our nose, we become a different-

This lack of person–

Setting the Context: Culture, History, and Puberty

As my sisters and I went about doing our daily chores, we choked on the dust stirred up by the herd of cattle and goats that had just arrived in our compound. . . . These animals were my bride wealth, negotiated by my parents and the family of the man who had been chosen as my husband. . . . I am considered to be a woman, so I am ready to marry, have children, and assume adult privileges and responsibilities. My name is Telelia ole Mariani. I am 14 years old.

(quoted in Wilson, Ngige, & Trollinger, 2003, p. 95)

As you can see in this quotation from a girl in rural Nigeria, throughout most of history and even today in agrarian cultures, having sex as a teenager was “normal.” The reason is that puberty was often society’s signal to find a spouse (Schlegel, 1995; Schlegel & Barry, 1991). The fact that a young person’s changing body meant entering a new adult stage of life produced a different attitude toward the physical changes. In our culture, we downplay puberty because we don’t want teenagers to act on their sexual feelings for years. In traditional societies, people might celebrate the changes in a coming-

Celebrating Puberty

Puberty rites were emotional events, carefully scripted to highlight a young person’s entrance into adulthood. Often, children were removed from their families and asked to perform challenging tasks. There was anxiety (“Can I really do this thing?”) and feelings of awe and self-

So as this photo shows in one South African tribe, after a private group initiation, boys returned to their tribe and were labeled as “warriors” in a community celebration. In the Amazon, males were required to prove their manhood by killing a large animal and then, metaphorically, “die”—by drinking a hallucinogen and spending time in isolation to “be born again” as adults. Among the Masai of Africa, male children first faced the challenge of undergoing a painful circumcision without showing distress. After passing this test, they entered a segregated compound to learn military maneuvers before proudly returning home and taking wives (Feixa, 2011).

For girls, menstruation was the standard marker to celebrate one’s arrival into womanhood. In the traditional Navajo Kinaalda ceremony, for instance, girls in their first or second menstrual cycle, guided by a female mentor, performed the long-

Today, however, girls may menstruate at age 10 or even 9. At that age—

The Declining Age of Puberty

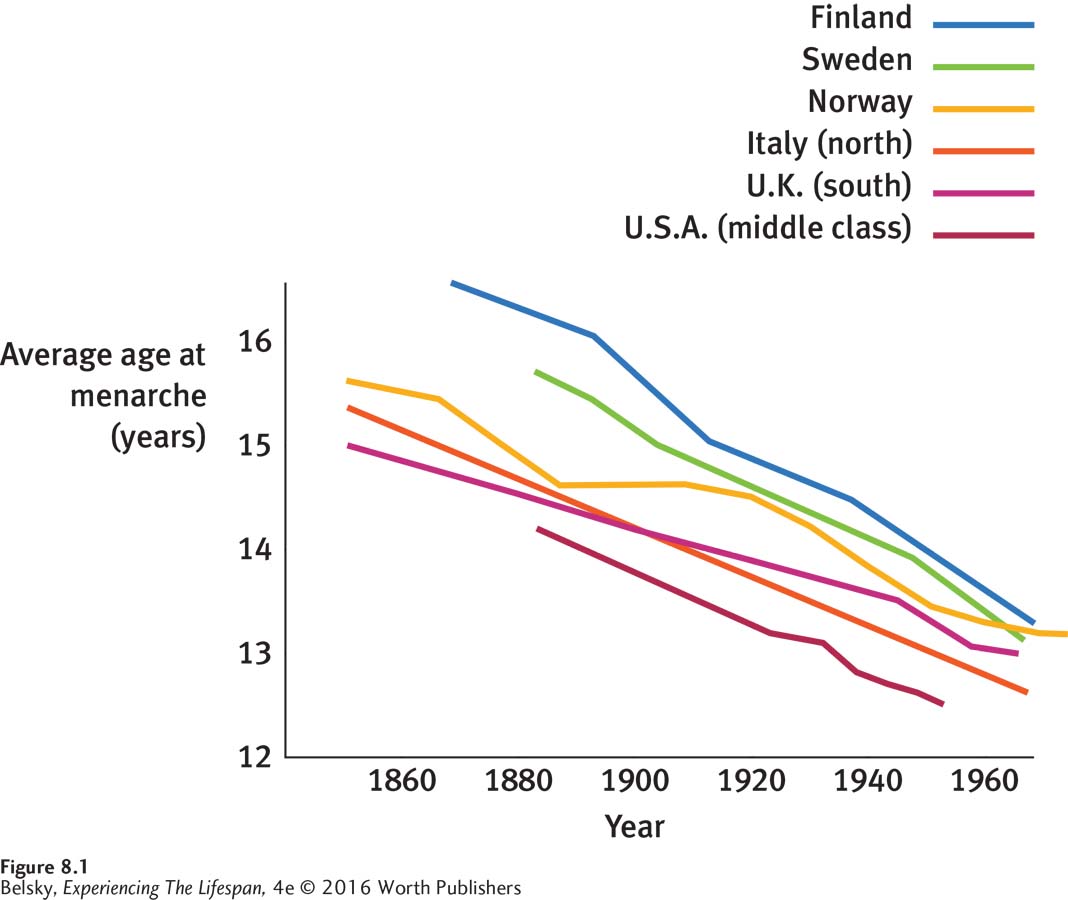

You can see this fascinating decline, called the secular trend in puberty, in Figure 8.1. In the 1860s, the average age of menarche, or first menstruation, in northern Europe was over 17 (Tanner, 1978). In the 1960s, in the developed world, it dropped to under 13 (Parent and others, 2003). Then, after a pause, about 20 years ago, the menarche marker began to slide downward again (Lee & Styne, 2013).

This means, a century ago, many girls could not get pregnant until their late teens. Today, many girls can have babies before their teenage years.

Researchers typically use menarche as their benchmark for charting the secular trend because it is an obvious sign of being able to have a child. The male signal of fertility, spermarche, or first ejaculation of live sperm, is a hidden event.

In addition, because it reflects better nutrition, in the same way as with stunting in early childhood (remember Chapter 3), we can use the secular trend in puberty as an index of a nation’s economic development. In the United States, African American girls begin to menstruate at close to age 12. In impoverished African nations, such as Senegal, the average age of menarche is over 16 (Parent and others, 2003)!

Given that nutrition is intimately involved, what exactly sets puberty off? For answers, let’s focus on the hormonal systems that program the physical changes.

The Hormonal Programmers

Puberty is programmed by two command centers. One system, located in the adrenal glands at the top of the kidneys, begins to release its hormones at about age 6 to 8, several years before children show observable signs of puberty. The adrenal androgens, whose output increases to reach a peak in the early twenties, eventually produce (among other events) pubic hair development, skin changes, body odor, and, as you will read later in this chapter, our first feelings of sexual desire (McClintock & Herdt, 1996).

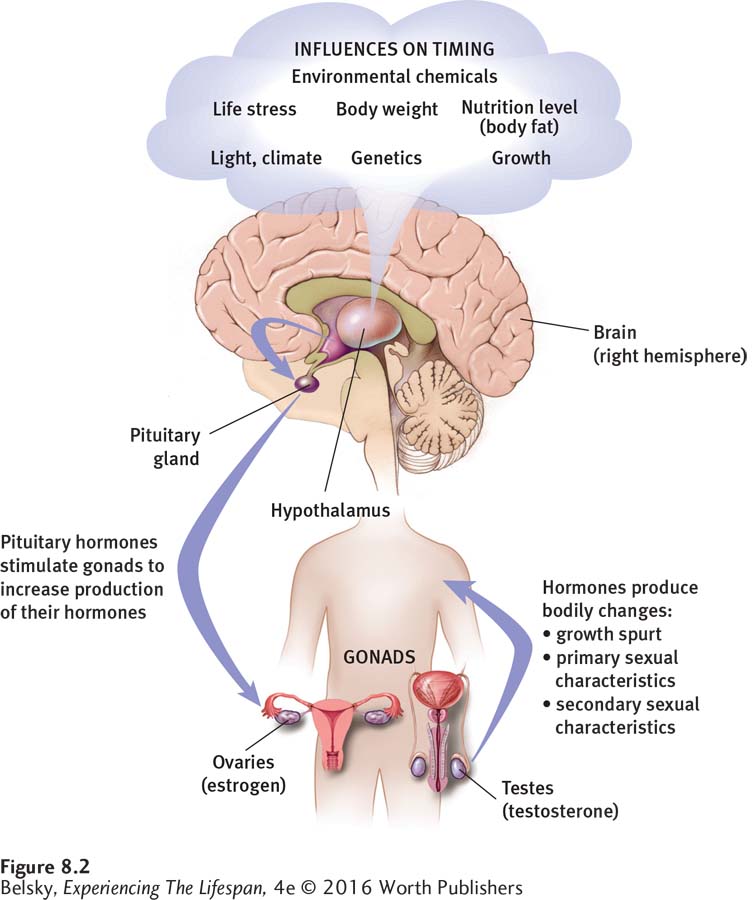

About two years later, the most important command center kicks in. Called the HPG axis—because it involves the hypothalamus (in the brain), the pituitary (a gland at the base of the brain), and the gonads (the ovaries and the testes)—this system produces the major body changes.

As you can see in Figure 8.2, puberty is set off by a three-

As the blood concentrations of estrogens and testosterone float upward, these hormones unleash a physical transformation. Estrogens produce females’ changing shape by causing the hips to widen and the uterus and breasts to enlarge. They set in motion the cycle of reproduction, stimulating the ovaries to produce eggs. Testosterone causes the penis to lengthen, promotes the growth of facial and body hair, and is responsible for a dramatic increase in muscle mass and other internal masculine changes.

Boys and girls both produce estrogens and testosterone. Testosterone and the adrenal androgens are the desire hormones. They are responsible for sexual arousal in females and males. However, women produce mainly estrogens. The concentration of testosterone is roughly eight times higher in boys after puberty than it is in girls; in fact, this classic “male” hormone is responsible for all the physical changes in boys.

Now, to return to our earlier question: What primes the triggering hypothalamic hormone? As Figure 8.2 illustrates, many forces help unleash the pulsating hypothalamic bursts—

The Physical Changes

Puberty causes a total psychological as well as physical transformation. As the hormones flood the body, they affect specific brain regions, making teenagers more emotional, sensitive to social cues, and interested in taking risks (as you will read in Chapter 9). Scientists divide the physical changes into three categories:

Primary sexual characteristics refer to the body changes directly involved in reproduction. The growth of the penis and menstruation are examples of primary sexual characteristics.

Secondary sexual characteristics is the label for the hundreds of other changes that accompany puberty, such as breast development, the growth of pubic hair, voice changes, and alterations in the texture of the skin.

The growth spurt merits its own special category. At puberty—

as should come as no surprise— there is a dramatic increase in height and weight.

Now, let’s offer a motion picture of these changes, first in girls and then in boys.

For Girls

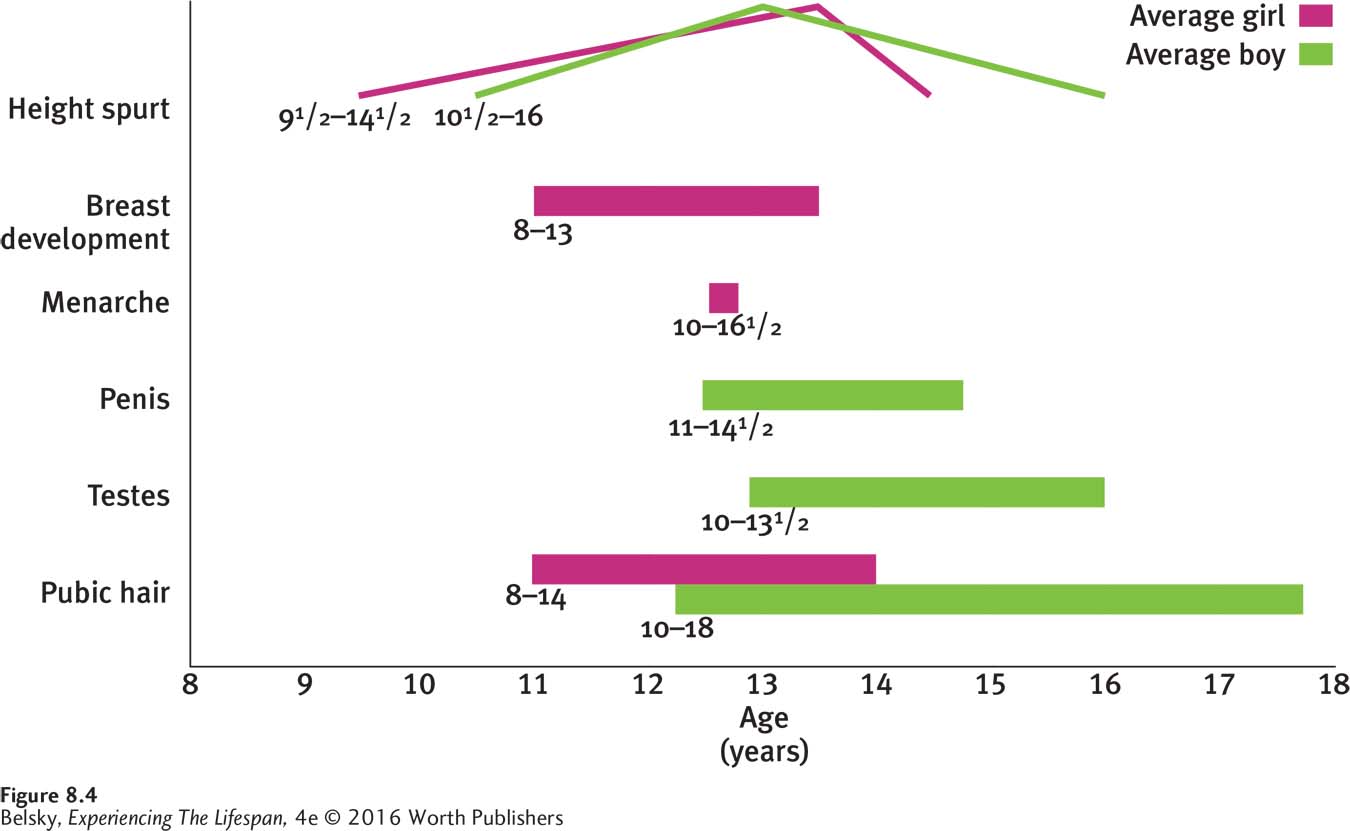

The first sign of puberty in girls is the growth spurt. During late childhood, girls’ growth picks up speed, accelerates, and then begins to decrease (Abbassi, 1998). On a visit to my 11-

About six months after the growth spurt begins, girls start to develop breasts and pubic hair. On average, girls’ breasts take about four years to grow to their adult form (Tanner, 1955, 1978).

Menarche typically occurs in the middle to final stages of breast and pubic hair development when growth is winding down (Christensen and others, 2010; Peper & Dahl, 2013; Lee & Styne, 2013). So you can tell your 12-

When they reach menarche, can girls get pregnant? Yes, but there is often a window of infertility until the system fully gears up. Does puberty unfold in the same way for every girl? The answer is no. Because the hormonal signals are complex, in some girls, pubic hair development (programmed by the adrenal androgens) is underway before the breasts begin to enlarge. Occasionally, a girl does grow much taller after she begins to menstruate.

The most fascinating variability relates to the rate of change. Some children are developmental “tortoises.” Their progression through puberty is slow-

New research suggests the pace at which children progress through puberty is affected by when the process starts. Girls who begin to develop earlier often proceed at a slower rate. Late starters pass through puberty for a shorter time. So if your 13-

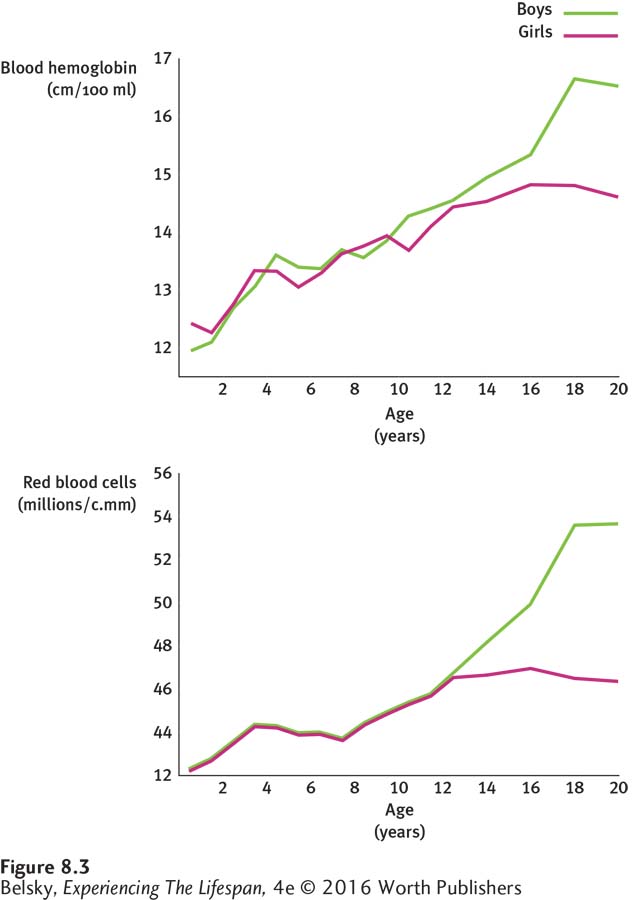

In tracking puberty in females, researchers focus on charting pubic hair and breast development because they can measure these external secondary sexual changes in stages. But the internal changes are equally dramatic. During puberty the uterus grows, the vagina lengthens, and the hips develop a cushion of fat. The vocal cords get longer, the heart gets bigger, and the red blood cells carry more oxygen. So, in addition to looking very different, after puberty, girls become much stronger (Archibald, Graber, & Brooks-

For Boys

In boys, researchers also chart how the penis, testicles, and pubic hair develop in stages. However, because these organs of reproduction begin developing first, boys still look like children to the outside world for a year or two after their bodies start changing. Voice changes, the growth of body hair, and that other visible sign of being a man—

Recall from Chapter 5 that elementary school boys and girls are roughly the same size. Then, during the puberty growth spurt, males shoot up an incredible average of 8 inches, compared to 4 inches for girls (Tanner, 1978). Boys also become far stronger than the other sex.

One reason lies in the tremendous increase in muscle mass. Another lies in the dramatic cardiovascular changes. At puberty, boys’ hearts increase in weight by more than one-

Do you know seventh or eighth-

Their long legs and large feet explain why, in their early teens, boys look so gawky (and unattractive!). Adding to the problem is the crackly voice produced by the growing larynx, the wispy look of beginning facial hair, and the fact that during puberty a boy’s nose and ears grow before the rest of his face catches up. Plus, the increased activity of the sweat glands and enlarged pores leads to the condition that results in so much emotional agony: acne. Although girls also suffer from acne, boys are more vulnerable to this condition because testosterone, which males produce in abundance, produces changes in the hair and skin.

Are Boys on a Later Timetable? A Bit

Now, visit a middle school and you will be struck by the fact that boys, on average, appear to reach puberty two years later than girls. But appearances can be deceiving. In girls, as I mentioned earlier, the externally visible signs of puberty, such as the growth spurt and breast development, take place toward the beginning of the sequence. For boys, the hidden development—

If we look at the real sign of fertility, the timetables for girls and boys are not very far apart. In one study, boys reported that spermarche occurred at roughly age 13, only about six months later than the average age of menarche (Stein & Reiser, 1994).

Figure 8.4, below, graphically summarizes some changes I have been discussing. Now, let’s explore the numbers inside the chart. Why do children undergo puberty at such different ages?

Individual Differences in Puberty Timetables

I’m seventeen already. But I still look like a kid. I get teased a lot, especially by the other guys. . . . Girls aren’t interested in me, either, because most of them are taller than I am. When will I grow up?

(adapted from an on-

The gender difference in puberty timetables can cause anxiety. As an early-

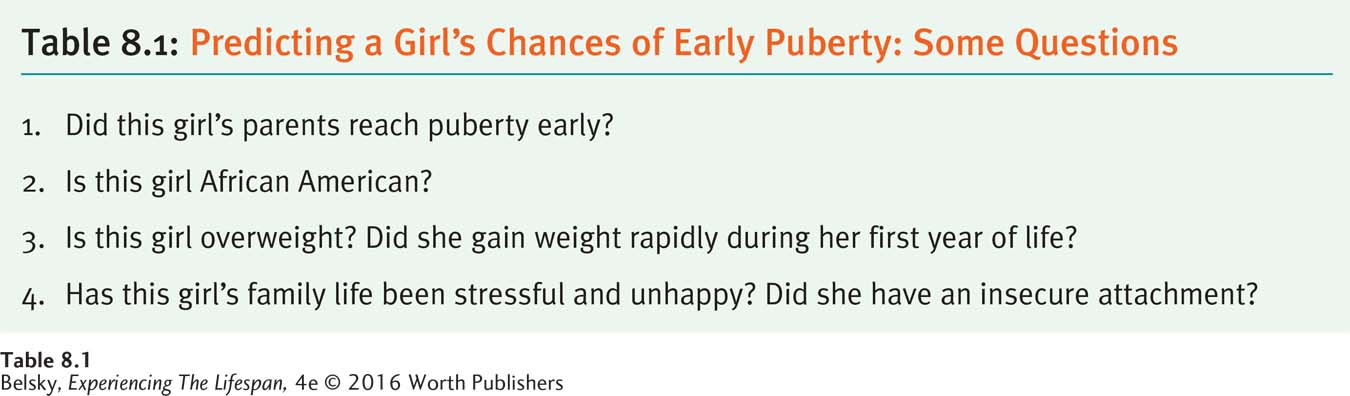

Not unexpectedly, genetics is important. Identical twins go through puberty at roughly the same ages (Silventoinen and others, 2008; Lee & Styne, 2013). Asian Americans tend to be slightly behind other U.S. children in puberty timetables (Sun and others, 2002). African American and Hispanic boys and girls are ahead of other North American groups (Rosenfield, Lipton, & Drum, 2009; Lee & Styne, 2013).

But remember that in impoverished African countries—

Overweight and Early Puberty (It’s All About Girls)

The answer is yes—

Recall that this finding dovetails with the research in Chapter 5, suggesting that our overweight path is set in motion early in life. Now—

Now let’s turn to a more astonishing environmental influence predicting puberty, specifically in girls—

Family Stress and Early Puberty (Again, It’s About Girls)

Drawing on an evolutionary psychology perspective, some developmentalists argue that when family stress is intense, nature might build in a mechanism to accelerate sexual maturity and free a child from an inhospitable nest (Belsky, Steinberg, & Draper, 1991). Just as stress in the womb “instructs” the baby to store fat (recall the fetal programming hypothesis in Chapter 2), researchers believe that an unhappy childhood signals the body to expect a short life and pushes adult fertility to a younger age (Belsky, Houts, & Pasco Fearon, 2010).

I must emphasize that “genetics” is the most important force predicting your puberty timetable (when your mother or father developed). But, if a girl is temperamentally vulnerable, controlling for every other influence (genetics, body weight, and so on), her family life makes its small, tantalizing contribution, too (Ellis and others, 2011b). Early-

Why—

Table 8.1 summarizes these points by spelling out questions that predict a female child’s chance of reaching puberty at a younger-

Now that I’ve described the physical process, let’s shift to an insider’s perspective, exploring how children feel about three classic signs of puberty—

An Insider’s View of Puberty

If you think back to how you felt about your changing body during puberty, you probably remember a mixture of emotions: fear, pride, embarrassment, excitement. Now, imagine how you would react if a researcher asked you to describe your inner state. Would you want to talk about how you really felt? The reluctance of pre-

The Breasts

In a classic study, researchers used this indirect strategy to explore how girls feel in relation to their parents while undergoing that most visible sign of becoming a woman—

Because society strongly values this symbol of being a woman (and our contemporary culture sees bigger as better!), other research suggests that U.S. girls feel proud of their developing breasts (Brooks-

Menstruation

Think of being a Navajo girl and knowing that when you begin to menstruate, you enter a special spiritual state. Compare this with the less-

Luckily, upper-

Positive responses make a difference. In contrast to earlier research, about half of these young women described menarche as positive or “no big deal.” But negative emotions linger. Even when they described their mothers as supportive, 1 in 3 students remembered feeling “disgusted” or, more likely, ambivalent—

First Ejaculation

Daughters must confide in their mothers about menarche because this change demands specific coping techniques. Spermarche, as I mentioned earlier, is hidden, because this event doesn’t require instructions from the outside world. Who talks to male adolescents about first ejaculation, and how do teenagers feel about their signal of becoming a man? Read these memories from some 18-

I woke up the next morning and my sheets were pasty. . . . After you wake up your mind is kind of happy and then you realize: “Oh my God, this is my wet dream!”

(quoted in Stein & Reiser, 1994, p. 380)

My mom, she knew I had them. It was all over my sheets and bedspread and stuff, but she didn’t say anything, didn’t tease me and stuff. She never asked if I wanted to talk about it—

(quoted in Stein & Reiser, 1994, p. 377)

Most of these boys reported that they needed to be secretive. They didn’t want to let anyone know. And notice from the second quotation—

Is this tendency for children to hide the symptoms of puberty around the parent of the other gender programmed into evolution to help teenagers emotionally separate from their families? We do not know. Where we do have massive scientific information is on the emotional impact of being early or late.

Being Early: It Can Be a Problem for Girls

Imagine being an early-

Actually, the timing of development matters, but again the results differ for boys and girls. Early-

Unfortunately, the research is consistently downbeat for the other sex: Hundreds of studies suggest early-

EARLY-

Because they are so busy testing the limits, in one classic study, early-

Then, there is the main concern with having a mature body early on: having unprotected sex. Because they may not have the cognitive abilities to resist this social pressure and often have older boyfriends, early-

EARLY-

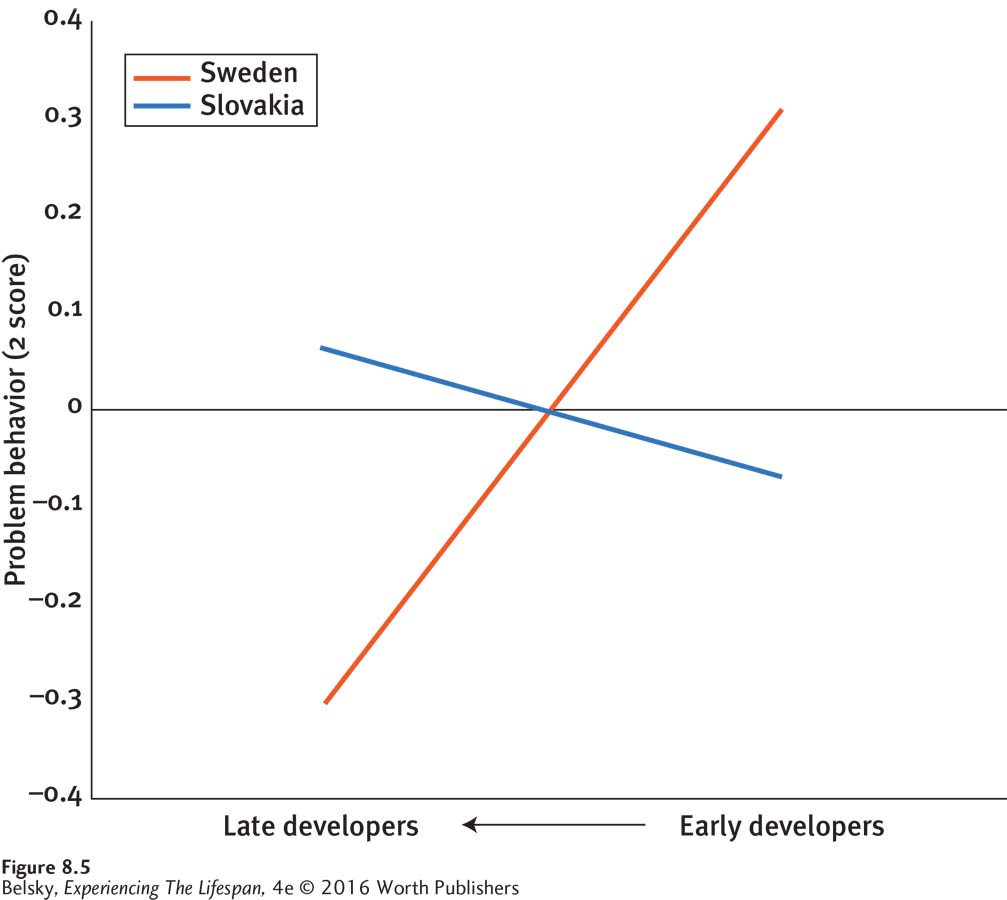

So far, I’ve been painting a dismal portrait of early-

Most important, these negative effects happen mainly when there are other risk factors in a child’s life. If a girl is exposed to harsh parenting (Deardorff and others, 2013) or if she is living in poverty, then, yes, early maturation can be the straw that breaks the camel’s back (Lynne-

The risks linked with maturing early also seem dependent on the society in which a girl grows up. In one interesting international comparison, while early-

This brings up that important teenage milieu: school. In a classic study, researchers (Simmons & Blyth, 1987) found that early-

Based on these findings, developmentalists have argued that it’s best not to “warehouse” boys and girls in middle schools during the stressful pubertal years (see Eccles & Roeser, 2003). But, the following study suggests we might rethink this classic scientific advice.

In tracking students in 36 rural school systems that did and did not offer middle school, the researchers were surprised to find that bullying was less frequent among the sixth graders who moved to middle schools. Moreover, the middle schoolers reported having more supportive class environments than children who remained in K–

This study highlights the fact that with pre-

Wrapping Up Puberty

Now, let’s summarize these messages:

Children’s reactions to puberty depend on the environment in which they physically mature. Negative feelings are more likely to occur when society looks down on a given sign of development (as with menstruation) or when the physical changes are not valued in a person’s particular group (as with breast development in ballerinas). Living in a sexually permissive society or changing to a non-

nurturing school during puberty magnifies the stress of body changes. With early-

maturing girls, we should take special steps to arrange the right body– Having an adult body at a young age is dangerous for girls, but only when the changes happen in a high-environment fit. risk milieu. Therefore, when a girl reaches puberty early, it’s important to arrange her life with special care. Communication about puberty should be improved—

especially for boys. While some contemporary mothers may be doing a fine job discussing menstruation with their daughters, boys, in particular, seem to enter puberty without any guidance about what to expect (Omar, McElderry, & Zakharia, 2003).

INTERVENTIONS: Minimizing Puberty Distress

Given these findings, what are the lessons for parents? What changes should society make?

LESSONS FOR PARENTS. It’s tempting for parents to avoid discussing puberty because children are so sensitive about their changing bodies (see Elliot, 2012; Hyde and others, 2013). This reluctance is a mistake. Developmentalists urge parents to discuss what is happening with a same-

Finally, parents of early-

LESSONS FOR SOCIETY. No matter what a child’s puberty timetable, the implicit message of this section is that the school environment matters tremendously at this gateway-

It also seems critical to provide more adequate puberty education. Think back to what you wanted to know about your changing body (“My breasts don’t look right”; “My penis has a strange shape”), and you will realize that offering a few fifth-

UNESCO has developed global guidelines aimed at teaching young children (aged 5 to 8) to respect their bodies. But, with the exception of a few European nations, schools routinely ignore this document—

Tying It All Together

Question 8.1

In contrast to earlier times, give the main reason why our culture can’t celebrate puberty today?

Today, puberty occurs a decade or more before we can fully reach adult life.

Question 8.2

You notice that your 11-

(a) The initial hypothalamic hormone triggers the pituitary to produce its hormones, which cause the ovaries and testes to mature and produce their hormones, which, in turn, produce the body changes. (b) Estrogens, testosterone, and the adrenal androgens.

Question 8.3

Kendra has recently begun to menstruate. Calista has just shot up in height. Carl is developing facial hair. Statistically speaking, which child is at the beginning of puberty?

Calista

Question 8.4

Brianna, an overweight second grader, has a harsh, rejecting family life. Based on this chapter, you might predict that Briana should enter puberty earlier/later than her peers.

earlier

Question 8.5

Based simply on knowing a child’s puberty timetable, spell out who is most at risk of getting into trouble (e.g., with drugs or having unprotected sex) as a teen.

An early maturing girl

Question 8.6

You are on an international advisory committee charged with developing programs to help children cope emotionally with puberty. What recommendations might you make?

Possible recommendations: Pay special attention to providing nurturing schools in sixth and seventh grade. Push for more adequate, “honest” puberty education at a younger age, possibly in a format—