4.7Most Eukaryotic Genes Are Mosaics of Introns and Exons

Most Eukaryotic Genes Are Mosaics of Introns and Exons

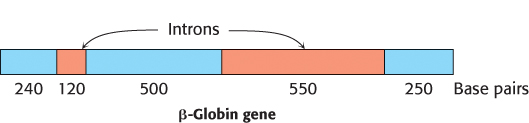

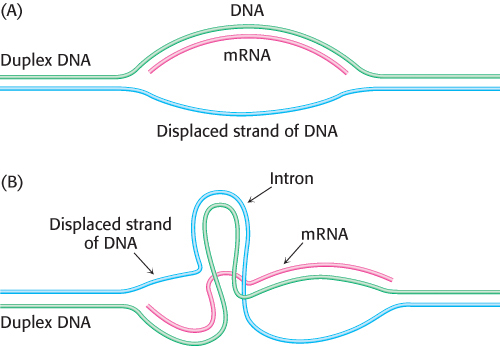

In bacteria, polypeptide chains are encoded by a continuous array of triplet codons in DNA. For many years, genes in higher organisms were assumed to be organized in the same manner. This view was unexpectedly shattered in 1977, when investigators discovered that most eukaryotic genes are discontinuous. The mosaic nature of eukaryotic genes was revealed by electron microscopic studies of hybrids formed between mRNA and a segment of DNA containing the corresponding gene (Figure 4.36). For example, the gene for the β chain of hemoglobin is interrupted within its amino acid-

RNA processing generates mature RNA

At what stage in gene expression are introns removed? Newly synthesized RNA molecules (pre-

128

Splicing is a complex operation that is carried out by spliceosomes, which are assemblies of proteins and small RNA molecules (snRNA). RNA plays the catalytic role (Section 29.3). Spliceosomes recognize signals in the nascent RNA that specify the splice sites. Introns nearly always begin with GU and end with an AG that is preceded by a pyrimidine-

Many exons encode protein domains

Most genes of higher eukaryotes, such as birds and mammals, are split. Lower eukaryotes, such as yeast, have a much higher proportion of continuous genes. In prokaryotes, split genes are extremely rare. Have introns been inserted into genes in the evolution of higher organisms? Or have introns been removed from genes to form the streamlined genomes of prokaryotes and simple eukaryotes? Comparisons of the DNA sequences of genes encoding evolutionarily conserved proteins suggest that introns were present in ancestral genes and were lost in the evolution of organisms that have become optimized for very rapid growth, such as prokaryotes. The positions of introns in some genes are at least 1 billion years old. Furthermore, a common mechanism of splicing developed before the divergence of fungi, plants, and vertebrates, as shown by the finding that mammalian cell extracts can splice yeast RNA.

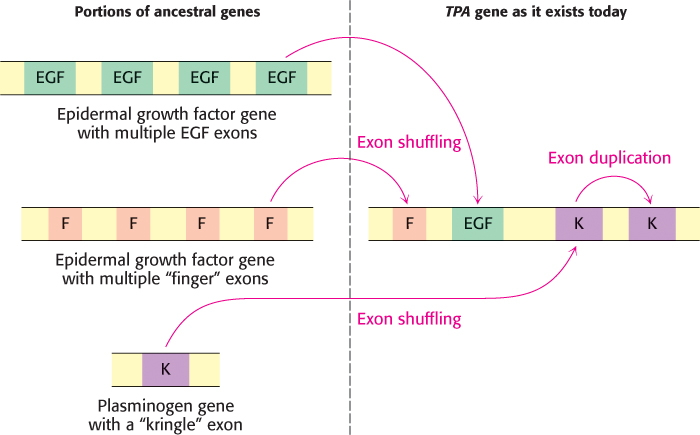

What advantages might split genes confer? Many exons encode discrete structural and functional domains of proteins. An attractive hypothesis is that new proteins arose in evolution by the rearrangement of exons encoding discrete structural elements, binding sites, and catalytic sites, a process called exon shuffling. Because it preserves functional units but allows them to interact in new ways, exon shuffling is a rapid and efficient means of generating novel genes (Figure 4.40). Figure 4.41 shows the composition of a gene that was formed in part by exon shuffling. DNA can break and recombine in introns with no deleterious effect on encoded proteins. In contrast, the exchange of sequences within different exons usually leads to loss of function.

Another advantage of split genes is the potential for generating a series of related proteins by alternative splicing of the primary transcript. For example, a precursor of an antibody-

129