24.2Amino Acids Are Made from Intermediates of the Citric Acid Cycle and Other Major Pathways

Amino Acids Are Made from Intermediates of the Citric Acid Cycle and Other Major Pathways

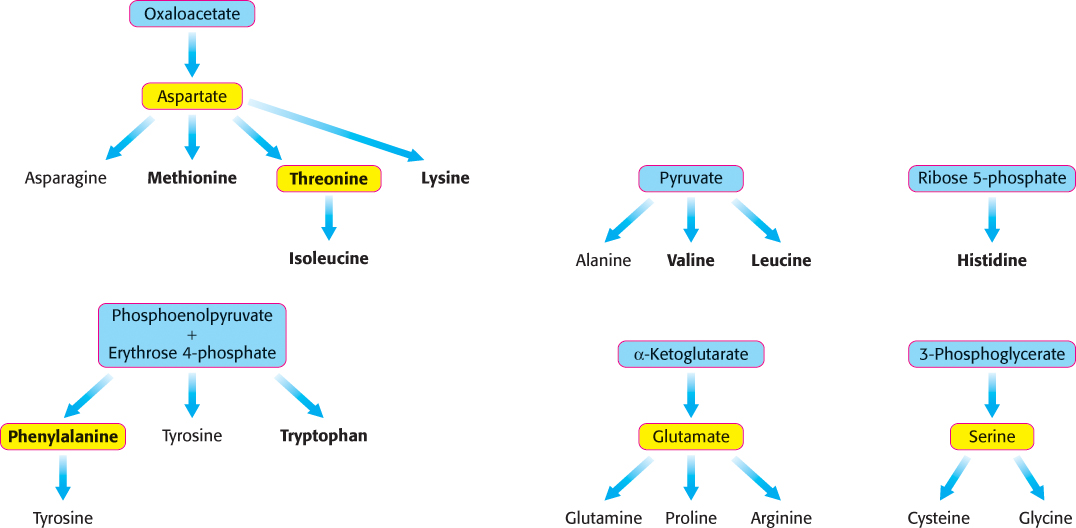

Thus far, we have considered the conversion of N2 into NH4+ and the assimilation of NH4+ into glutamate and glutamine. We turn now to the biosynthesis of the other amino acids, the majority of which obtain their nitrogen from glutamate or glutamine. The pathways for the biosynthesis of amino acids are diverse. However, they have an important common feature: their carbon skeletons come from intermediates of glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, or the citric acid cycle. On the basis of these starting materials, amino acids can be grouped into six biosynthetic families (Figure 24.5).

Human beings can synthesize some amino acids but must obtain others from their diet

|

Nonessential |

Essential |

|---|---|

|

Alanine |

Histidine |

|

Arginine |

Isoleucine |

|

Asparagine |

Leucine |

|

Aspartate |

Lysine |

|

Cysteine |

Methionine |

|

Glutamate |

Phenylalanine |

|

Glutamine |

Threonine |

|

Glycine |

Tryptophan |

|

Proline |

Valine |

|

Serine |

|

|

Tyrosine |

|

Most microorganisms, such as E. coli, can synthesize the entire basic set of 20 amino acids, whereas human beings cannot make 9 of them. The amino acids that must be supplied in the diet are called essential amino acids, whereas the others, which can be synthesized if dietary content is insufficient, are termed nonessential amino acids (Table 24.1). These designations refer to the needs of an organism under a particular set of conditions. For example, enough arginine is synthesized by the urea cycle to meet the needs of an adult, but perhaps not those of a growing child. A deficiency of even one amino acid results in a negative nitrogen balance. In this state, more protein is degraded than is synthesized, and so more nitrogen is excreted than is ingested.

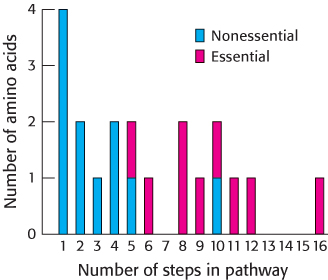

The nonessential amino acids are synthesized by quite simple reactions, whereas the pathways for the formation of the essential amino acids are quite complex. For example, the nonessential amino acids alanine and aspartate are synthesized in a single step from pyruvate and oxaloacetate, respectively. In contrast, the pathways for the essential amino acids require from 5 to 16 steps (Figure 24.6). The sole exception to this pattern is arginine, inasmuch as the synthesis of this nonessential amino acid de novo requires 10 steps. Typically, however, it is made in only 3 steps from ornithine as part of the urea cycle. Tyrosine, classified as a nonessential amino acid because it can be synthesized in 1 step from phenylalanine, requires 10 steps to be synthesized from scratch and is essential if phenylalanine is not abundant. We begin with the biosynthesis of nonessential amino acids.

720

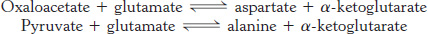

Aspartate, alanine, and glutamate are formed by the addition of an amino group to an alpha-ketoacid

Three α-ketoacids—

These reactions are carried out by pyridoxal phosphate-

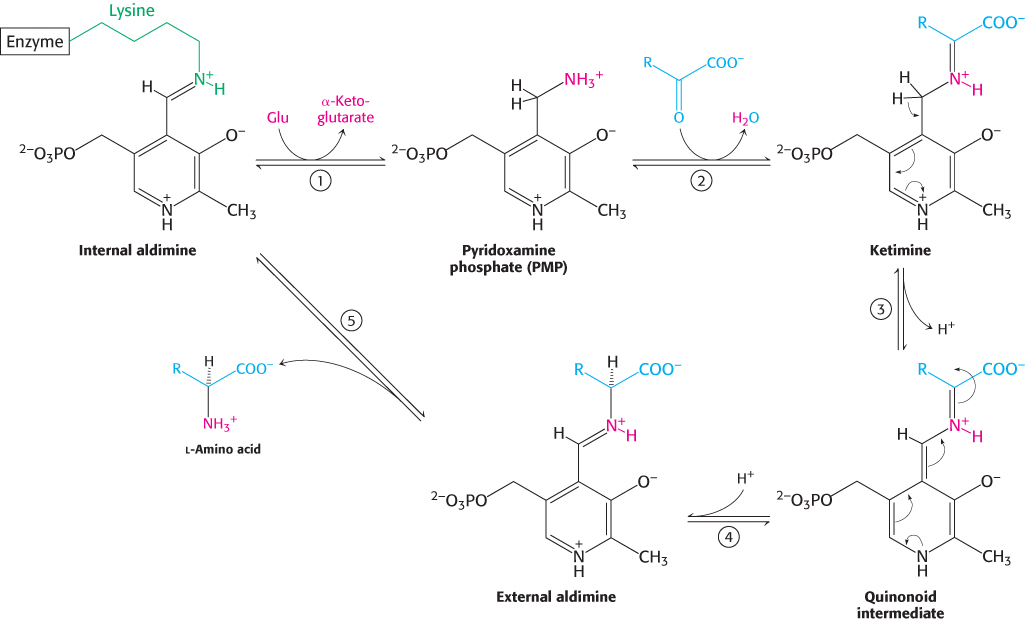

In Section 23.3, we considered the mechanism of aminotransferases as applied to the metabolism of amino acids. Let us review the aminotransferase mechanism as it operates in the biosynthesis of amino acids (Figure 23.11). The reaction pathway begins with pyridoxal phosphate in a Schiff-

721

A common step determines the chirality of all amino acids

Aspartate aminotransferase is the prototype of a large family of PLP-

Aspartate aminotransferase is the prototype of a large family of PLP-

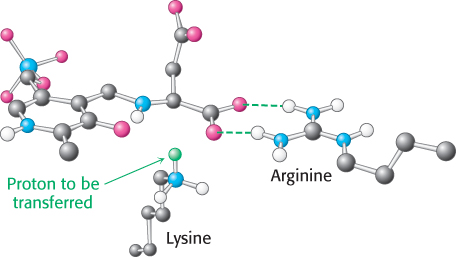

An essential step in the transamination reaction is the protonation of the quinonoid intermediate to form the external aldimine. The chirality of the amino acid formed is determined by the direction from which this proton is added to the quinonoid form (Figure 24.8). The interaction between the conserved arginine residue and the α-carboxylate group helps orient the substrate so that the lysine residue transfers a proton to the bottom face of the quinonoid intermediate, generating an aldimine with an l configuration at the Cα center.

The formation of asparagine from aspartate requires an adenylated intermediate

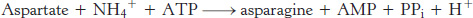

The formation of asparagine from aspartate is chemically analogous to the formation of glutamine from glutamate. Both transformations are amidation reactions and both are driven by the hydrolysis of ATP. The actual reactions are different, however. In bacteria, the reaction for the asparagine synthesis is

Thus, the products of ATP hydrolysis are AMP and PPi rather than ADP and Pi. Aspartate is activated by adenylation rather than by phosphorylation.

We have encountered this mode of activation in fatty acid degradation and will see it again in lipid and protein synthesis.

In mammals, the nitrogen donor for asparagine is glutamine rather than ammonia as in bacteria. Ammonia is generated by hydrolysis of the side chain of glutamine and directly transferred to activated aspartate, bound in the active site. An advantage is that the cell is not directly exposed to NH4+, which is toxic at high levels to human beings and other mammals. The use of glutamine hydrolysis as a mechanism for generating ammonia for use within the same enzyme is a motif common throughout biosynthetic pathways.

722

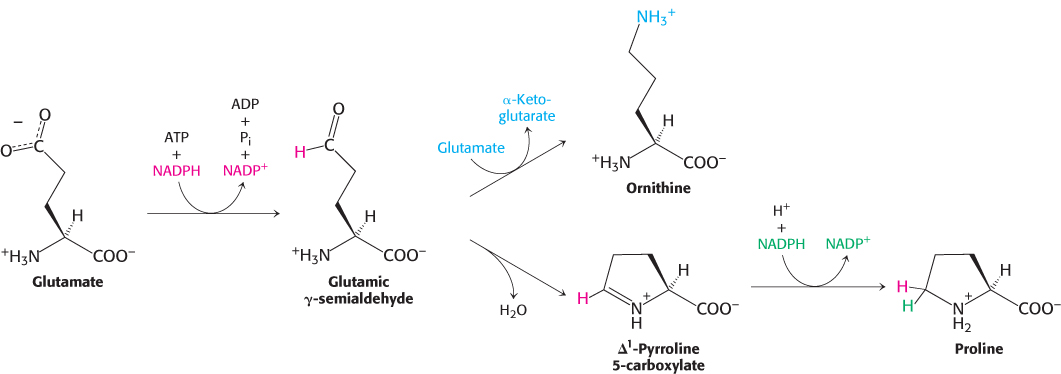

Glutamate is the precursor of glutamine, proline, and arginine

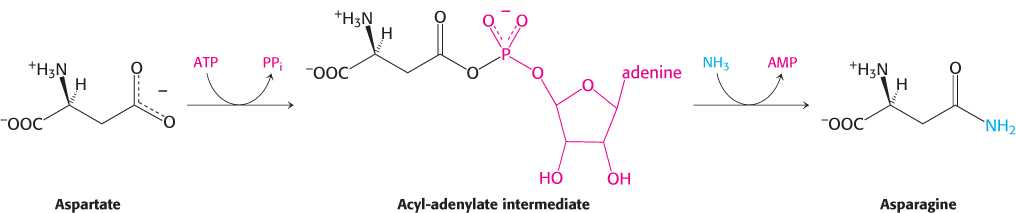

The synthesis of glutamate by the reductive amination of α-ketoglutarate has already been discussed, as has the conversion of glutamate into glutamine. Glutamate is the precursor of two other nonessential amino acids: proline and arginine. First, the γ-carboxyl group of glutamate reacts with ATP to form an acyl phosphate. This mixed anhydride is then reduced by NADPH to an aldehyde.

Glutamic γ-semialdehyde cyclizes with a loss of H2O in a nonenzymatic process to give Δ1-pyrroline 5-

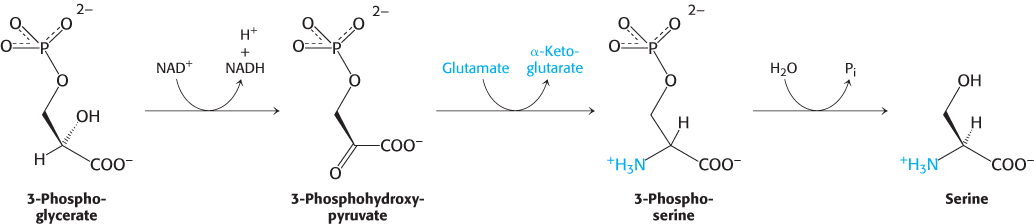

3-Phosphoglycerate is the precursor of serine, cysteine, and glycine

Serine is synthesized from 3-

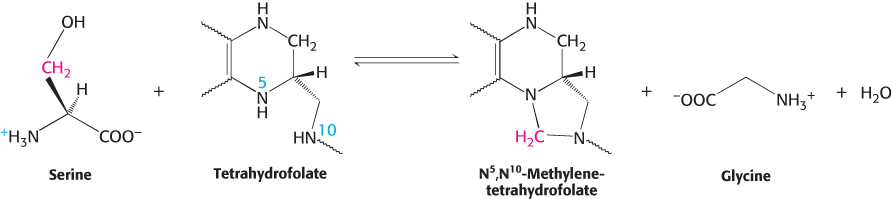

Serine is the precursor of cysteine and glycine. As we shall see, the conversion of serine into cysteine requires the substitution of a sulfur atom derived from methionine for the side-

723

This interconversion is catalyzed by serine hydroxymethyltransferase, a PLP enzyme that is homologous to aspartate aminotransferase. The formation of the Schiff base of serine renders the bond between its α- and β-carbon atoms susceptible to cleavage, enabling the transfer of the β-carbon to tetrahydrofolate and producing the Schiff base of glycine.

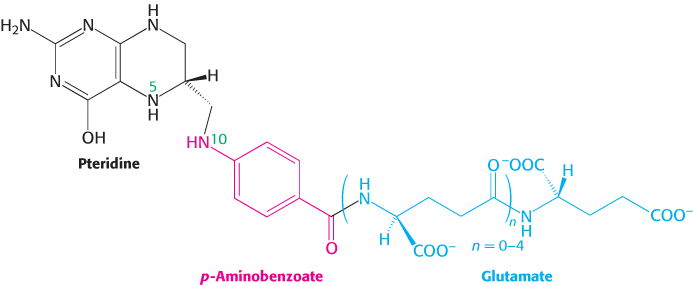

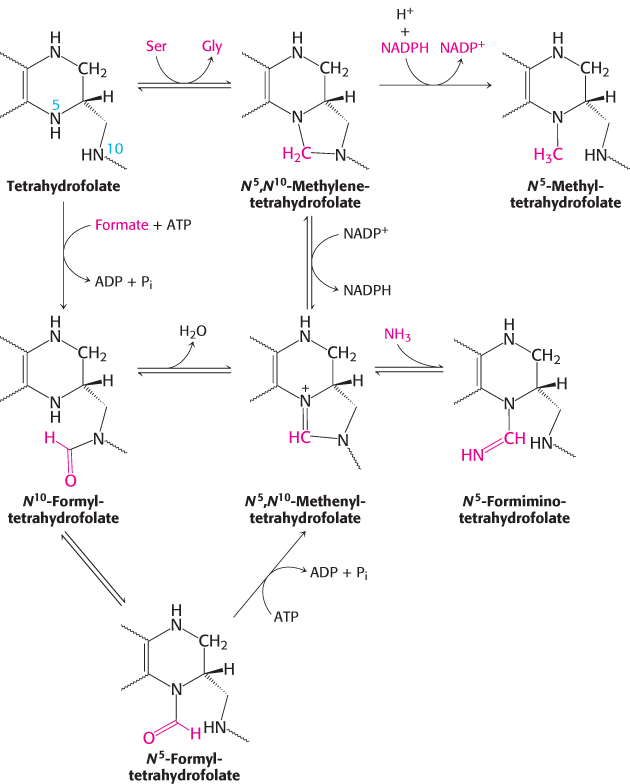

Tetrahydrofolate carries activated one-carbon units at several oxidation levels

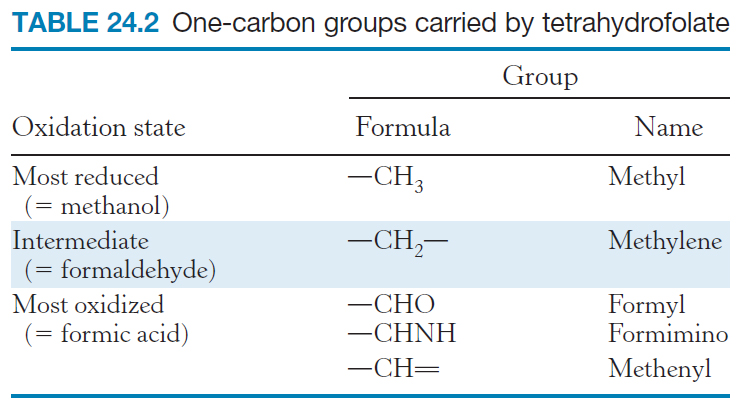

Tetrahydrofolate (also called tetrahydropteroylglutamate) is a highly versatile carrier of activated one-

The one-

The one-

724

These tetrahydrofolate derivatives serve as donors of one-

Thus, one-

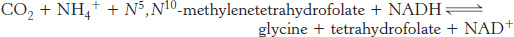

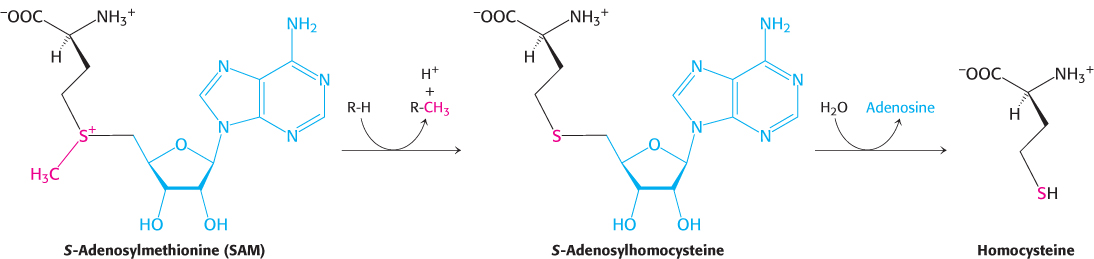

S-Adenosylmethionine is the major donor of methyl groups

Tetrahydrofolate can carry a methyl group on its N-

725

The methyl group of the methionine unit is activated by the positive charge on the adjacent sulfur atom, which makes the molecule much more reactive than N5-methyltetrahydrofolate. The synthesis of S-adenosylmethionine is unusual in that the triphosphate group of ATP is split into pyrophosphate and orthophosphate; the pyrophosphate is subsequently hydrolyzed to two molecules of Pi. S-

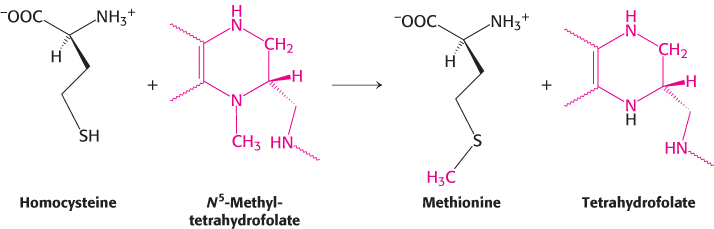

Methionine can be regenerated by the transfer of a methyl group to homocysteine from N5-methyltetrahydrofolate, a reaction catalyzed by methionine synthase (also known as homocysteine methyltransferase).

The coenzyme that mediates this transfer of a methyl group is methylcobalamin, derived from vitamin B12. In fact, this reaction and the rearrangement of l-methylmalonyl CoA to succinyl CoA, catalyzed by a homologous enzyme, are the only two B12-dependent reactions known to take place in mammals. Another enzyme that converts homocysteine into methionine without vitamin B12 also is present in many organisms.

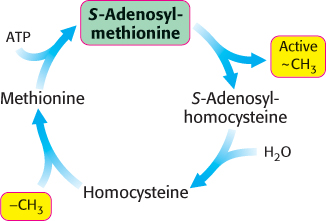

These reactions constitute the activated methyl cycle (Figure 24.11). Methyl groups enter the cycle in the conversion of homocysteine into methionine and are then made highly reactive by the addition of an adenosyl group, which makes the sulfur atoms positively charged and the methyl groups much more electrophilic. The high transfer potential of the S-methyl group enables it to be transferred to a wide variety of acceptors. Among the acceptors modified by S-adenosylmethionine are specific bases in bacterial DNA. For instance, the methylation of DNA protects bacterial DNA from cleavage by restriction enzymes (Section 9.3). Methylation is also important for the synthesis of phospholipids (Section 26.1).

726

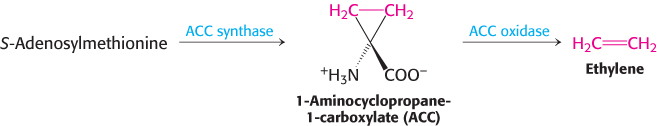

S-Adenosylmethionine is also the precursor of ethylene, a gaseous plant hormone that induces the ripening of fruit. S-Adenosylmethionine is cyclized to a cyclopropane derivative that is then oxidized to form ethylene. The Greek philosopher Theophrastus recognized more than 2000 years ago that sycamore figs do not ripen unless they are scraped with an iron claw. The reason is now known: Wounding triggers ethylene production, which in turn induces ripening.

Cysteine is synthesized from serine and homocysteine

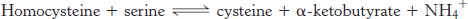

In addition to being a precursor of methionine in the activated methyl cycle, homocysteine is an intermediate in the synthesis of cysteine. Serine and homocysteine condense to form cystathionine. This reaction is catalyzed by cystathionine β-synthase. Cystathionine is then deaminated and cleaved to cysteine and α-ketobutyrate by cystathionine γ-lyase or cystathionase. Both of these enzymes utilize PLP and are homologous to aspartate aminotransferase. The net reaction is

Note that the sulfur atom of cysteine is derived from homocysteine, whereas the carbon skeleton comes from serine.

High homocysteine levels correlate with vascular disease

People with elevated serum levels of homocysteine (homocysteinemia) or the disulfide-

People with elevated serum levels of homocysteine (homocysteinemia) or the disulfide-

727

Shikimate and chorismate are intermediates in the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids

We turn now to the biosynthesis of essential amino acids. These amino acids are synthesized by plants and microorganisms, and those in the human diet are ultimately derived primarily from plants. The essential amino acids are formed by much more complex routes than are the nonessential amino acids. The pathways for the synthesis of aromatic amino acids in bacteria have been selected for discussion here because they are well understood and exemplify recurring mechanistic motifs.

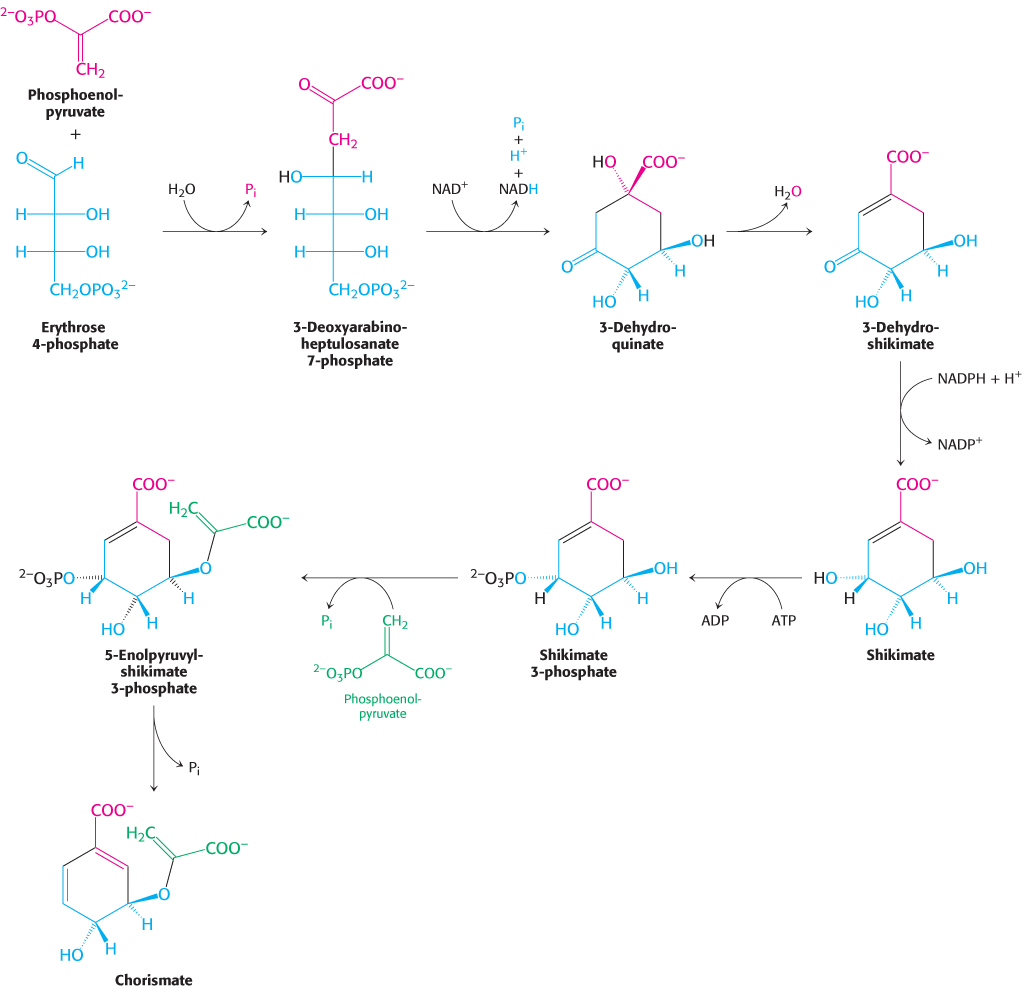

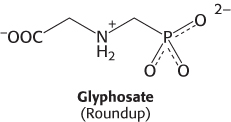

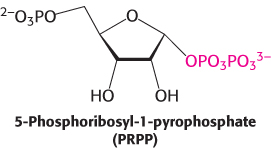

Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan are synthesized by a common pathway in E. coli (Figure 24.12). The initial step is the condensation of phosphoenolpyruvate (a glycolytic intermediate) with erythrose 4-

728

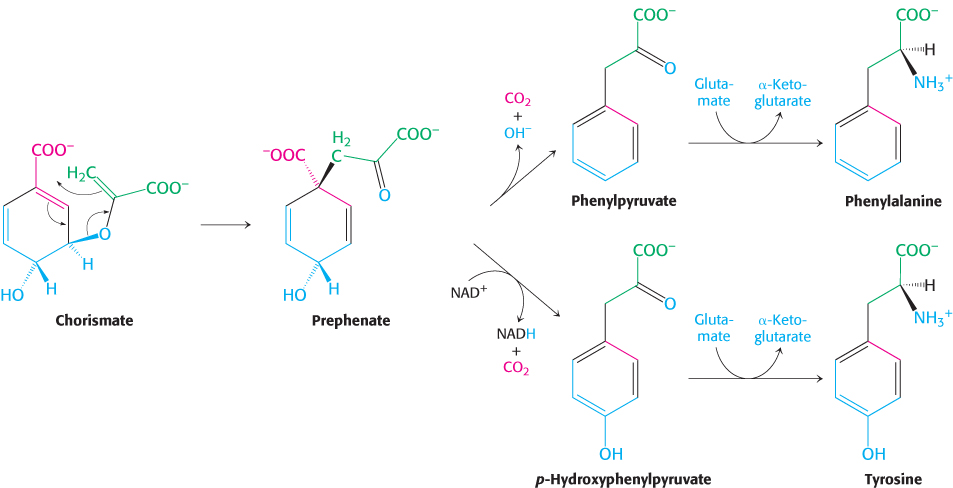

The pathway bifurcates at chorismate. Let us first follow the prephenate branch (Figure 24.13). A mutase converts chorismate into prephenate, the immediate precursor of the aromatic ring of phenylalanine and tyrosine. This fascinating conversion is a rare example of an electrocyclic reaction in biochemistry, mechanistically similar to the well-

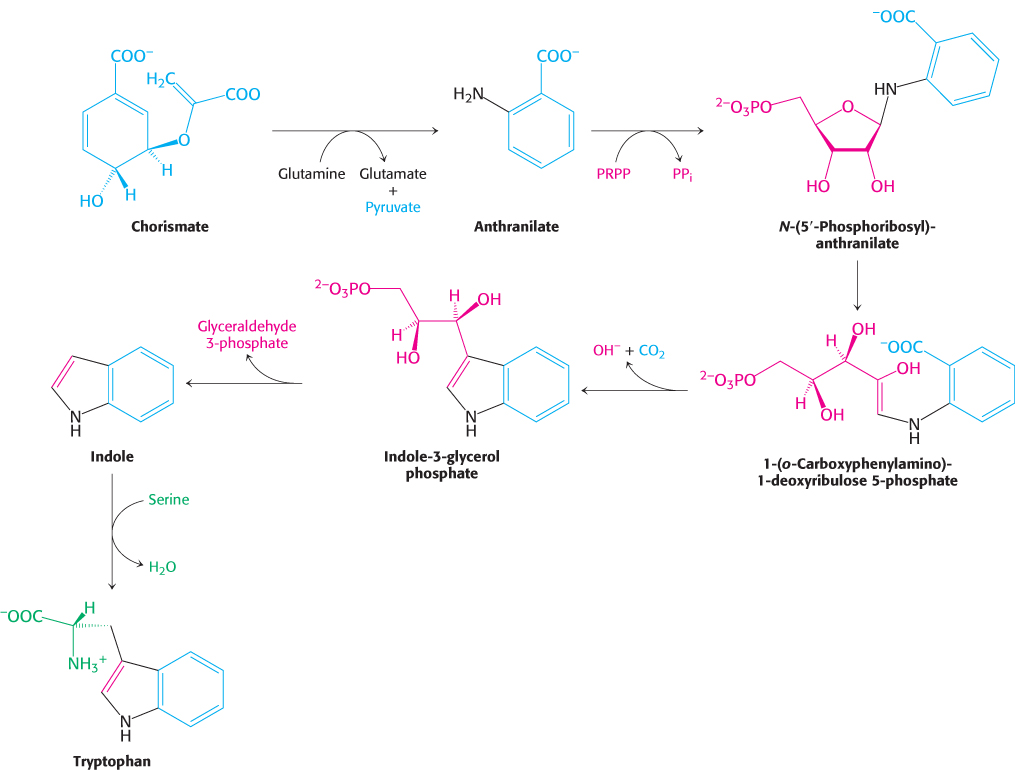

The branch starting with anthranilate leads to the synthesis of tryptophan (Figure 24.14). Chorismate acquires an amino group derived from the hydrolysis of the side chain of glutamine and releases pyruvate to form anthranilate. Anthranilate then condenses with 5-

729

Tryptophan synthase illustrates substrate channeling in enzymatic catalysis

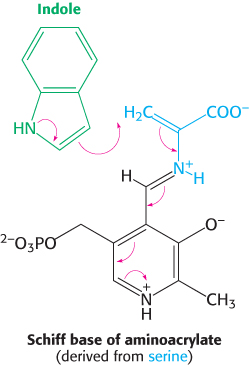

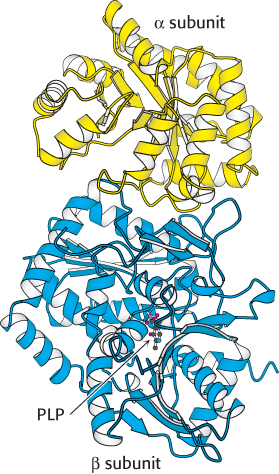

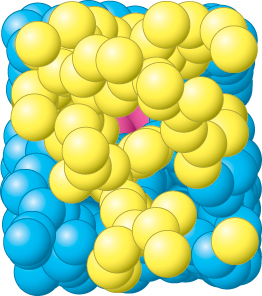

The E. coli enzyme tryptophan synthase, an α2β2 tetramer, can be dissociated into two α subunits and a β2 dimer (Figure 24.15). The α subunit catalyzes the formation of indole from indole-

FIGURE 24.15 Structure of tryptophan synthase. The structure of the complex formed by one α subunit (yellow) and one β subunit (blue). Notice that pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) is bound deeply inside the β subunit, a considerable distance from the α subunit.

FIGURE 24.15 Structure of tryptophan synthase. The structure of the complex formed by one α subunit (yellow) and one β subunit (blue). Notice that pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) is bound deeply inside the β subunit, a considerable distance from the α subunit.

The synthesis of tryptophan poses a challenge. Indole, a hydrophobic molecule, readily traverses membranes and would be lost from the cell if it were allowed to diffuse away from the enzyme. This problem is solved in an ingenious way. A 25-

730