9.3Restriction Enzymes Catalyze Highly Specific DNA-Cleavage Reactions

Restriction Enzymes Catalyze Highly Specific DNA-Cleavage Reactions

We next consider a hydrolytic reaction that results in the cleavage of DNA. Bacteria and archaea have evolved mechanisms to protect themselves from viral infections. Many viruses inject their DNA genomes into cells; once inside, the viral DNA hijacks the cell’s machinery to drive the production of viral proteins and, eventually, of progeny virus. Often, a viral infection results in the death of the host cell. A major protective strategy for the host is to use restriction endonucleases (restriction enzymes) to degrade the viral DNA on its introduction into a cell. These enzymes recognize particular base sequences, called recognition sequences or recognition sites, in their target DNA and cleave that DNA at defined positions. We have already considered the utility of these important enzymes for dissecting genes and genomes (Section 5.1). The most well-

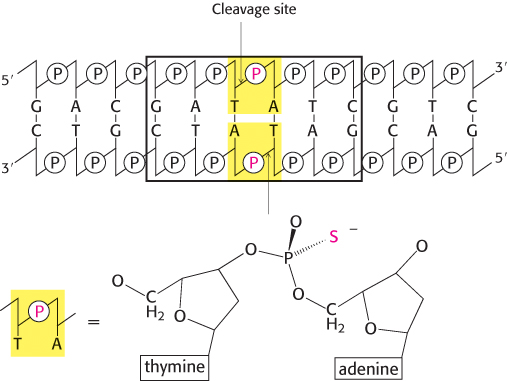

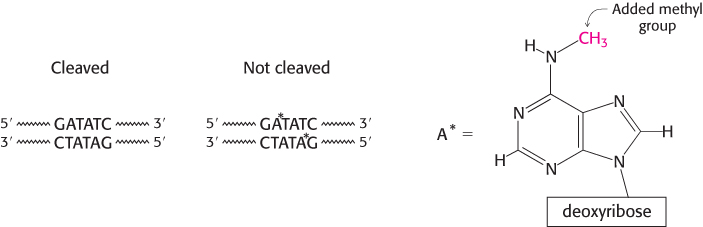

Restriction endonucleases must show tremendous specificity at two levels. First, they must not degrade host DNA containing the recognition sequences. Second, they must cleave only DNA molecules that contain recognition sites (hereafter referred to as cognate DNA) without cleaving DNA molecules that lack these sites. How do these enzymes manage to degrade viral DNA while sparing their own? In E. coli, the restriction endonuclease EcoRV cleaves double-

Restriction enzymes must cleave DNA only at recognition sites, without cleaving at other sites. Suppose that a recognition sequence is six base pairs long. Because there are 46, or 4096, sequences having six base pairs, the concentration of sites that must not be cleaved will be approximately 4000-

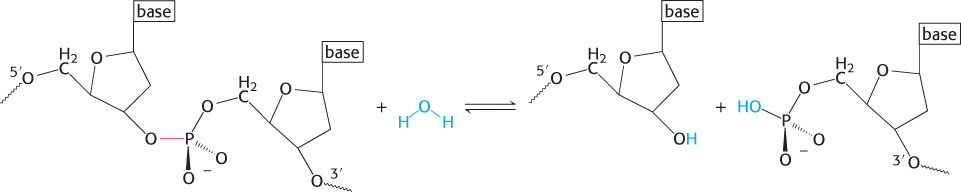

Cleavage is by in-line displacement of 3′-oxygen from phosphorus by magnesium-activated water

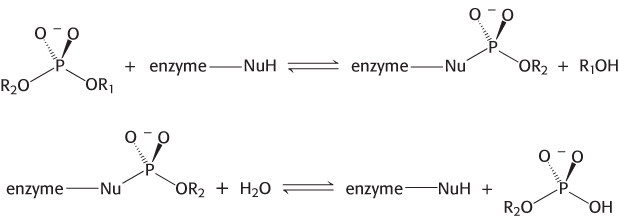

A restriction endonuclease catalyzes the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester backbone of DNA. Specifically, the bond between the 3′-oxygen atom and the phosphorus atom is broken. The products of this reaction are DNA strands with a free 3′-hydroxyl group and a 5′-phosphoryl group at the cleavage site (Figure 9.31). This reaction proceeds by nucleophilic attack at the phosphorus atom. We will consider two alternative mechanisms, suggested by analogy with the proteases. The restriction endonuclease might cleave DNA by mechanism 1 through a covalent intermediate, employing a potent nucleophile (Nu), or by mechanism 2 through direct hydrolysis:

270

Mechanism 1 (covalent intermediate)

Mechanism 2 (direct hydrolysis)

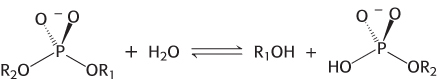

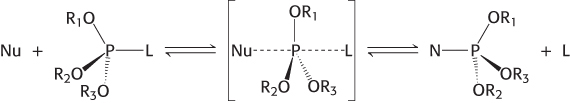

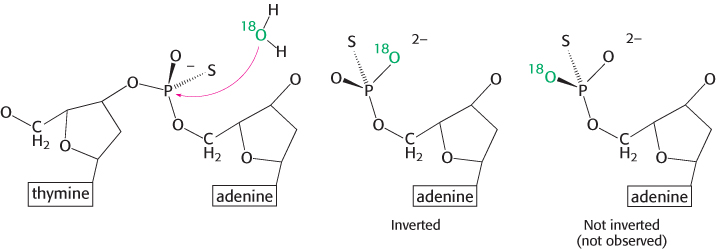

Each mechanism postulates a different nucleophile to attack the phosphorus atom. In either case, each reaction takes place by in-

The incoming nucleophile attacks the phosphorus atom, and a pentacoordinate transition state is formed. This species has a trigonal bipyramidal geometry centered at the phosphorus atom, with the incoming nucleophile at one apex of the two pyramids and the group that is displaced (the leaving group, L) at the other apex. Note that the displacement inverts the stereochemical conformation at the tetrahedral phosphorous atom, analogous to the interconversion of the R and S configurations around a tetrahedral carbon center (Section 2.1).

The two mechanisms differ in the number of times that the displacement takes place in the course of the reaction. In the first type of mechanism, a nucleophile in the enzyme (analogous to serine 195 in chymotrypsin) attacks the phosphate group to form a covalent intermediate. In a second step, this intermediate is hydrolyzed to produce the final products. In this case, two displacement reactions take place at the phosphorus atom. Consequently, the stereochemical configuration at the phosphorus atom would be inverted and then inverted again, and the overall configuration would be retained. In the second type of mechanism, analogous to that used by the aspartyl-

A difficulty is that the stereochemistry is not easily observed, because two of the groups bound to the phosphorus atom are simple oxygen atoms, identical with each other. This difficulty can be circumvented by replacing one oxygen atom with sulfur (producing a species called a phosphorothioate). Let us consider EcoRV endonuclease. This enzyme cleaves the phosphodiester bond between the T and the A at the center of the recognition sequence 5′-GATATC-

271

Restriction enzymes require magnesium for catalytic activity

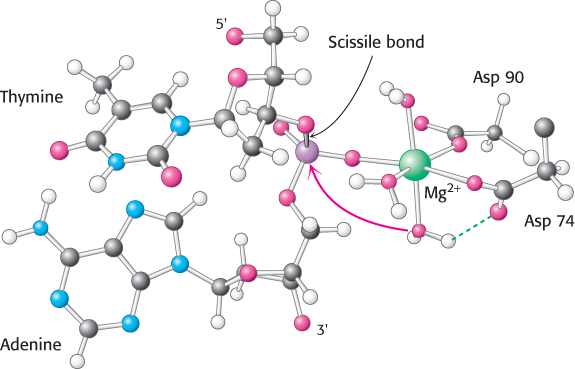

Many enzymes that act on phosphate-

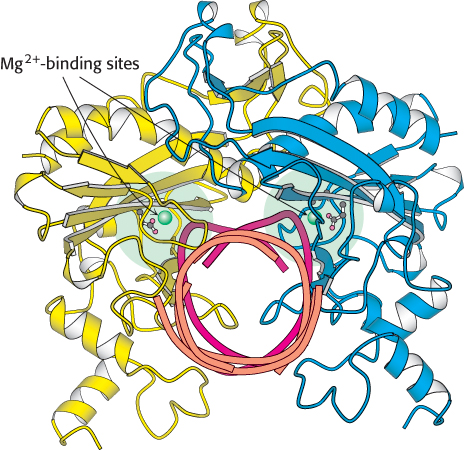

Direct visualization of the complex between EcoRV endonuclease and cognate DNA molecules in the presence of Mg2+ by crystallization has not been possible, because the enzyme cleaves the substrate under these circumstances. Nonetheless, metal ion complexes can be visualized through several approaches. In one approach, crystals of EcoRV endonuclease are prepared bound to oligonucleotides that contain the enzyme’s recognition sequence. These crystals are grown in the absence of magnesium to prevent cleavage; after their preparation, the crystals are soaked in solutions containing the metal. Alternatively, crystals have been grown with the use of a mutated form of the enzyme that is less active. Finally, Mg2+ can be replaced by metal ions such as Ca2+ that bind but do not result in much catalytic activity. In all cases, no cleavage takes place, and so the locations of the metal ion-

272

As many as three metal ions have been found to be present per active site. The roles of these multiple metal ions are still under investigation. One ion-

The complete catalytic apparatus is assembled only within complexes of cognate DNA molecules, ensuring specificity

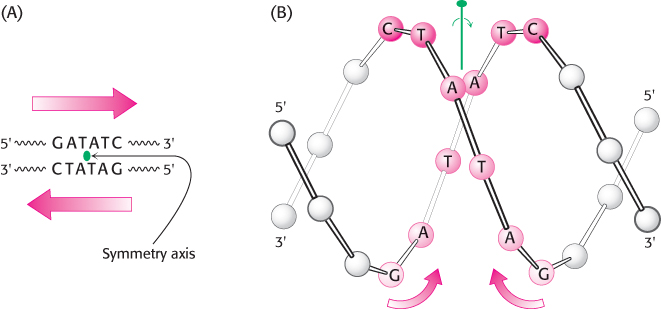

We now return to the question of specificity, the defining feature of restriction enzymes. The recognition sequences for most restriction endonucleases are inverted repeats. This arrangement gives the three-

The restriction enzymes display a corresponding symmetry: they are dimers whose two subunits are related by twofold rotational symmetry. The matching symmetry of the recognition sequence and the enzyme facilitates the recognition of cognate DNA by the enzyme. This similarity in structure has been confirmed by the determination of the structure of the complex between EcoRV endonuclease and DNA fragments containing its recognition sequence (Figure 9.36). The enzyme surrounds the DNA in a tight embrace.

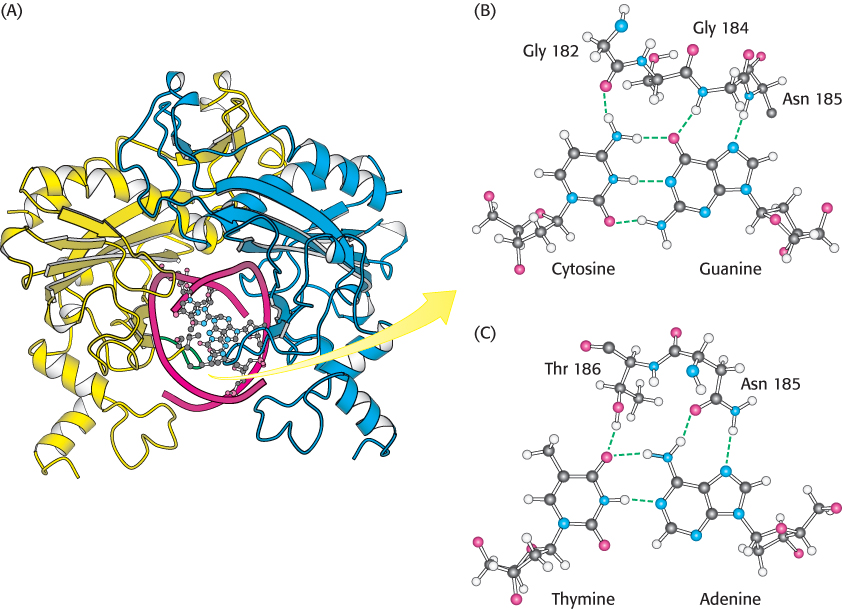

FIGURE 9.36 EcoRV embracing a cognate DNA molecule. (A) This view of the structure of EcoRV endonuclease bound to a cognate DNA fragment is down the helical axis of the DNA. The two protein subunits are in yellow and blue, and the DNA backbone is in red. Notice that the twofold axes of the enzyme dimer and the DNA are aligned. One of the DNA-

FIGURE 9.36 EcoRV embracing a cognate DNA molecule. (A) This view of the structure of EcoRV endonuclease bound to a cognate DNA fragment is down the helical axis of the DNA. The two protein subunits are in yellow and blue, and the DNA backbone is in red. Notice that the twofold axes of the enzyme dimer and the DNA are aligned. One of the DNA-273

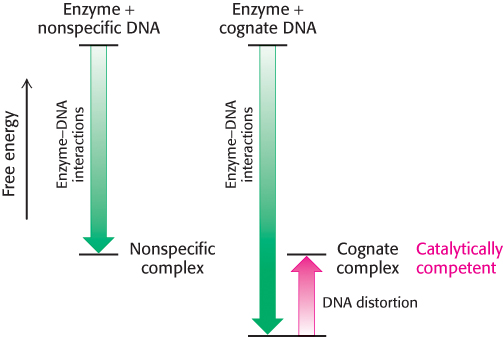

An enzyme’s binding affinity for substrates often determines specificity. Surprisingly, however, binding studies performed in the absence of magnesium have demonstrated that the EcoRV endonuclease binds to all sequences, both cognate and noncognate, with approximately equal affinity. Why, then, does the enzyme cleave only cognate sequences? The answer lies in a unique set of interactions between the enzyme and a cognate DNA sequence.

Within the 5′-GATATC-

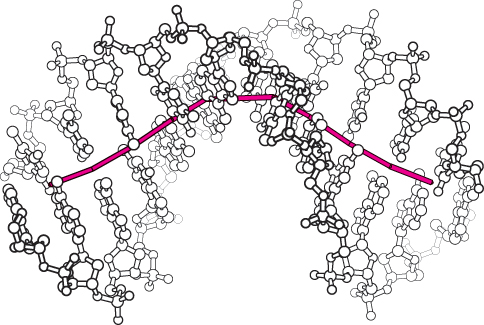

FIGURE 9.38 Nonspecific and cognate DNA within EcoRV endonuclease. A comparison of the positions of the nonspecific (orange) and the cognate DNA (red) within EcoRV. Notice that, in the nonspecific complex, the DNA backbone is too far from the enzyme to complete the magnesium ion-

FIGURE 9.38 Nonspecific and cognate DNA within EcoRV endonuclease. A comparison of the positions of the nonspecific (orange) and the cognate DNA (red) within EcoRV. Notice that, in the nonspecific complex, the DNA backbone is too far from the enzyme to complete the magnesium ion-The structures of complexes formed with noncognate DNA fragments are strikingly different from those formed with cognate DNA: the noncognate DNA conformation is not substantially distorted (Figure 9.38). This lack of distortion has important consequences with regard to catalysis. No phosphate is positioned sufficiently close to the active-

274

We can now see the role of binding energy in this strategy for attaining catalytic specificity. The distorted DNA makes additional contacts with the enzyme, increasing the binding energy. However, the increase in binding energy is canceled by the energetic cost of distorting the DNA from its relaxed conformation (Figure 9.39). Thus, for EcoRV endonuclease, there is little difference in binding affinity for cognate and nonspecific DNA fragments. However, the distortion in the cognate complex dramatically affects catalysis by completing the magnesium ion-

Host-cell DNA is protected by the addition of methyl groups to specific bases

How does a host cell harboring a restriction enzyme protect its own DNA? The host DNA is methylated on specific adenine bases within host recognition sequences by other enzymes called methylases (Figure 9.40). An endonuclease will not cleave DNA if its recognition sequence is methylated. For each restriction endonuclease, the host cell produces a corresponding methylase that marks the host DNA at the appropriate methylation site. These pairs of enzymes are referred to as restriction-

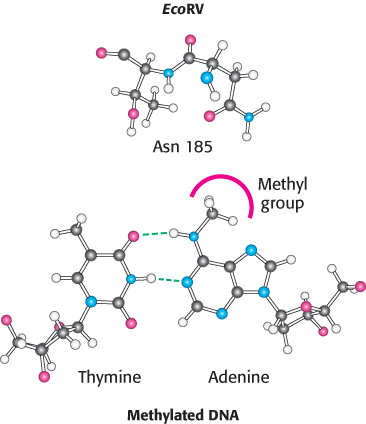

The distortion in the DNA explains how methylation blocks catalysis and protects host-

275

Type II restriction enzymes have a catalytic core in common and are probably related by horizontal gene transfer

Type II restriction enzymes are prevalent in Archaea and Bacteria. What can we tell of the evolutionary history of these enzymes? Comparison of the amino acid sequences of a variety of type II restriction endonucleases did not reveal significant sequence similarity between most pairs of enzymes. However, a careful examination of three-

Type II restriction enzymes are prevalent in Archaea and Bacteria. What can we tell of the evolutionary history of these enzymes? Comparison of the amino acid sequences of a variety of type II restriction endonucleases did not reveal significant sequence similarity between most pairs of enzymes. However, a careful examination of three-

These observations indicate that many type II restriction enzymes are indeed evolutionarily related. Analyses of the sequences in greater detail suggest that bacteria may have obtained genes encoding these enzymes from other species by horizontal gene transfer, the passing of pieces of DNA (such as plasmids) between species that provide a selective advantage in a particular environment. For example, EcoRI (from E. coli) and RsrI (from Rhodobacter sphaeroides) are 50% identical in sequence over 266 amino acids, clearly indicative of a close evolutionary relationship. However, these species of bacteria are not closely related. Thus, these species appear to have obtained the gene for these restriction endonucleases from a common source more recently than the time of their evolutionary divergence. Moreover, the codons used by the gene encoding EcoRI endonuclease to specify given amino acids are strikingly different from the codons used by most E. coli genes, which suggests that the gene did not originate in E. coli.

Horizontal gene transfer may be a common event. For example, genes that inactivate antibiotics are often transferred, leading to the transmission of antibiotic resistance from one species to another. For restriction-