24.4Amino Acids Are Precursors of Many Biomolecules

Amino Acids Are Precursors of Many Biomolecules

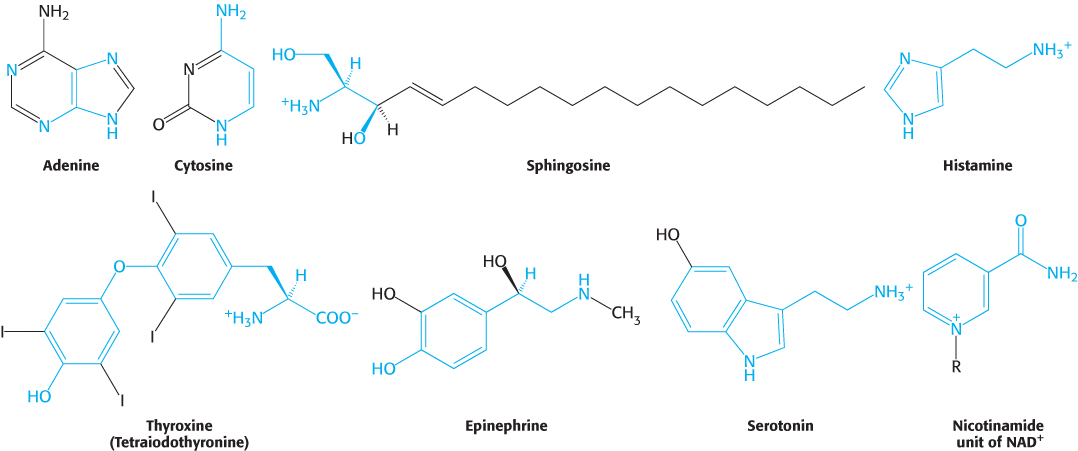

In addition to being the building blocks of proteins and peptides, amino acids serve as precursors of many kinds of small molecules that have important and diverse biological roles. Let us briefly survey some of the biomolecules that are derived from amino acids (Figure 24.22).

Purines and pyrimidines are derived largely from amino acids. The biosynthesis of these precursors of DNA, RNA, and numerous coenzymes will be discussed in detail in Chapter 25. The reactive terminus of sphingosine, an intermediate in the synthesis of sphingolipids, comes from serine. Histamine, a potent vasodilator, is derived from histidine by decarboxylation. Tyrosine is a precursor of thyroxine (tetraiodothyronine, a hormone that modulates metabolism), epinephrine (adrenaline), and melanin (a complex polymeric molecule responsible for skin pigmentation). The neurotransmitter serotonin (5-

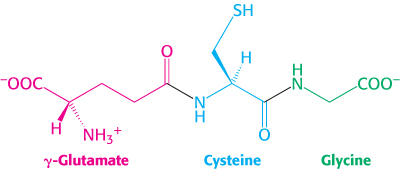

Glutathione, a gamma-glutamyl peptide, serves as a sulfhydryl buffer and an antioxidant

Glutathione, a tripeptide containing a sulfhydryl group, is a highly distinctive amino acid derivative with several important roles (Figure 24.23). For example, glutathione, present at high levels (∼5 mM) in animal cells, protects red blood cells from oxidative damage by serving as a sulfhydryl buffer (Section 20.5). It cycles between a reduced thiol form (GSH) and an oxidized form (GSSG) in which two tripeptides are linked by a disulfide bond.

GSSG is reduced to GSH by glutathione reductase, a flavoprotein that uses NADPH as the electron source. The ratio of GSH to GSSG in most cells is greater than 500. Glutathione plays a key role in detoxification by reacting with hydrogen peroxide and organic peroxides, the harmful by-

735

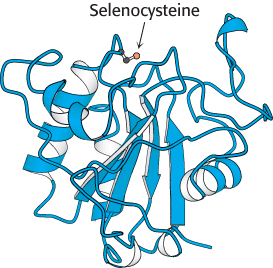

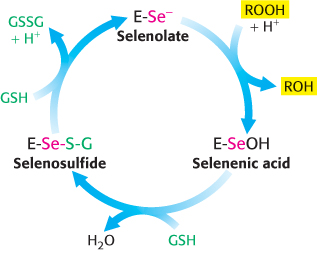

Glutathione peroxidase, the enzyme catalyzing this reaction, is remarkable in having a modified amino acid containing a selenium (Se) atom (Figure 24.24). Specifically, its active site contains the selenium analog of cysteine, in which selenium has replaced sulfur. The selenolate (E-

FIGURE 24.24 Structure of glutathione peroxidase. This enzyme, which has a role in peroxide detoxification, contains a selenocysteine residue in its active site.

FIGURE 24.24 Structure of glutathione peroxidase. This enzyme, which has a role in peroxide detoxification, contains a selenocysteine residue in its active site.

15N labeling: A pioneer’s account

“Myself as a Guinea Pig

… in 1944, I undertook, together with David Rittenberg, an investigation on the turnover of blood proteins of man. To this end I synthesized 66 g of glycine labeled with 35 percent 15N at a cost of $1000 for the 15N. On 12 February 1945, I started the ingestion of the labeled glycine. Since we did not know the effect of relatively large doses of the stable isotope of nitrogen and since we believed that the maximum incorporation into the proteins could be achieved by the administration of glycine in some continual manner, I ingested 1 g samples of glycine at hourly intervals for the next 66 hours …. At stated intervals, blood was withdrawn and after proper preparation the 15N concentrations of different blood proteins were determined.”

—David Shemin Bioessays 10(1989):30

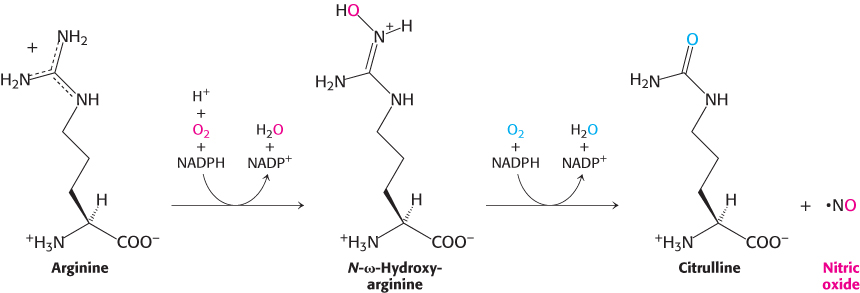

Nitric oxide, a short-lived signal molecule, is formed from arginine

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important messenger in many vertebrate signal-

736

Porphyrins are synthesized from glycine and succinyl coenzyme A

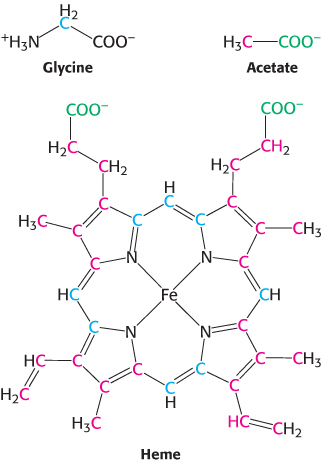

The participation of an amino acid in the biosynthesis of the porphyrin rings of hemes and chlorophylls was first revealed by isotope-

Experiments using 14C, which had just become available, revealed that 8 of the carbon atoms of heme in nucleated duck erythrocytes are derived from the α-carbon atom of glycine and none from the carboxyl carbon atom. Subsequent studies demonstrated that the other 26 carbon atoms of heme can arise from acetate. Moreover, the 14C in methyl-

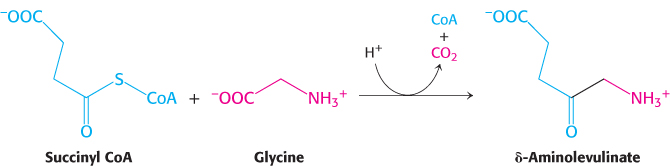

This highly distinctive labeling pattern suggested that acetate is converted to succinyl-

This reaction is catalyzed by δ-aminolevulinate synthase, a PLP enzyme present in mitochondria. Consistent with the labeling studies described earlier, the carbon atom from the carboxyl group of glycine is lost as carbon dioxide, while the α-carbon remains in δ-aminolevulinate.

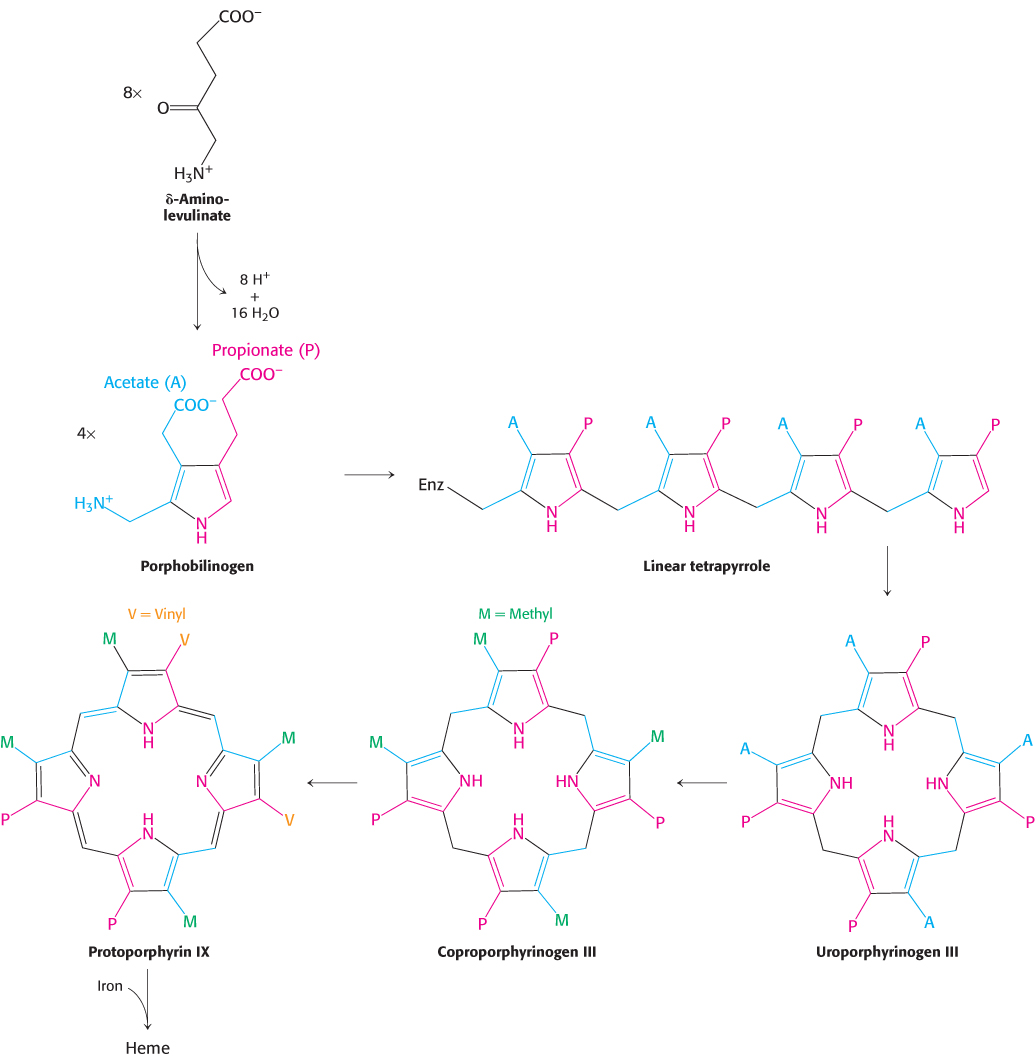

Two molecules of δ-aminolevulinate condense to form porphobilinogen, the next intermediate. Four molecules of porphobilinogen then condense head to tail to form a linear tetrapyrrole in a reaction catalyzed by porphobilinogen deaminase. The enzyme-

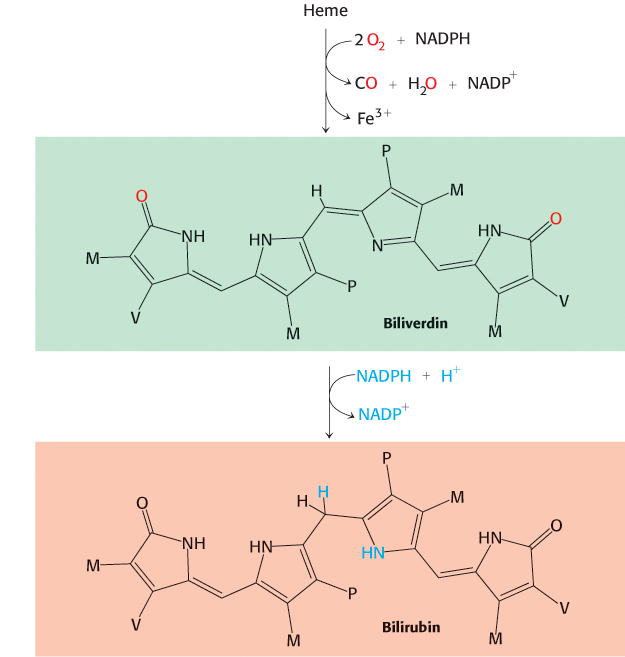

The porphyrin skeleton is now formed. Subsequent reactions alter the side chains and the degree of saturation of the porphyrin ring (Figure 24.28). Coproporphyrinogen III is formed by the decarboxylation of the acetate side chains. The desaturation of the porphyrin ring and the conversion of two of the propionate side chains into vinyl groups yield protoporphyrin IX. The chelation of iron finally gives heme, the prosthetic group of proteins such as myoglobin, hemoglobin, catalase, peroxidase, and cytochrome c. The insertion of the ferrous form of iron is catalyzed by ferrochelatase. Iron is transported in the plasma by transferrin, a protein that binds two ferric ions, and is stored in tissues inside molecules of ferritin (Section 32.4).

Studies with 15N-

737

Porphyrins accumulate in some inherited disorders of porphyrin metabolism

Porphyrias are inherited or acquired disorders caused by a deficiency of enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway. Porphyrin is synthesized in both the erythroblasts and the liver, and either one may be the site of a disorder. Congenital erythropoietic porphyria, for example, prematurely destroys erythrocytes. This disease results from insufficient cosynthase. In this porphyria, the synthesis of the required amount of uroporphyrinogen III is accompanied by the formation of very large quantities of uroporphyrinogen I, the useless symmetric isomer. Uroporphyrin I, coproporphyrin I, and other symmetric derivatives also accumulate. The urine of patients having this disease is red because of the excretion of large amounts of uroporphyrin I. Their teeth exhibit a strong red fluorescence under ultraviolet light because of the deposition of porphyrins. Furthermore, their skin is usually very sensitive to light because photoex-

Porphyrias are inherited or acquired disorders caused by a deficiency of enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway. Porphyrin is synthesized in both the erythroblasts and the liver, and either one may be the site of a disorder. Congenital erythropoietic porphyria, for example, prematurely destroys erythrocytes. This disease results from insufficient cosynthase. In this porphyria, the synthesis of the required amount of uroporphyrinogen III is accompanied by the formation of very large quantities of uroporphyrinogen I, the useless symmetric isomer. Uroporphyrin I, coproporphyrin I, and other symmetric derivatives also accumulate. The urine of patients having this disease is red because of the excretion of large amounts of uroporphyrin I. Their teeth exhibit a strong red fluorescence under ultraviolet light because of the deposition of porphyrins. Furthermore, their skin is usually very sensitive to light because photoex-

738