Understanding How and Why

science of human development

The science that seeks to understand how and why people of all ages and circumstances change or remain the same over time.

The science of human development seeks to understand how and why people—

Development over the life span is multi-

THINK CRITICALLY: What are the limitations of a scientific approach to human development?2

Science is especially necessary when the topic is human development. People disagree about what pregnant women should eat; where babies should sleep; when children should be punished; whether adults should go to college, marry, divorce, and have children; how people in late adulthood should approach aging, caregiving, and dying.

Some parents beat their children; other people put such parents in prison. Some people quit working as soon as they can; other people never retire. Everyone’s choices affect everyone else. Scientists seek to progress from personal opinions to proven facts, from wishes to evidence that might affect us all.

The Scientific Method

scientific method

A way to answer questions using empirical research and data-

As you surely realize, facts may be twisted, and applications sometimes spring from false assumptions. To rein in personal biases and avoid misinterpretations, researchers follow the scientific method (see Figure 1.1):

hypothesis

A specific prediction that can be tested.

empirical evidence

Evidence that is based on observation, experience, or experiment; not theoretical.

Begin with curiosity. Pose a question, guided by theory, research, or observation.

Develop a hypothesis. Shape the question into a hypothesis, a testable prediction.

Test the hypothesis. Conduct research to gather empirical evidence (data).

Draw conclusions. Use the evidence to support or refute the hypothesis.

Report the results. Share data, conclusions, limitations, and alternative explanations.

As you see, developmental scientists begin with curiosity and then seek facts, drawing conclusions after careful research.

replication

Repeating a study, usually using different participants, perhaps of another age, location, socioeconomic status (SES), or culture.

Replication—repeating the procedures and methods of a study with different participants—

This method is not foolproof. Scientists sometimes draw conclusions too hastily, misinterpret data, or ignore alternative perspectives.

Occasionally scientists discover, to their shock and horror, that another scientist has not followed the procedures outlined above. This is one reason that detailed procedures and replication are needed. Asking questions and testing hypotheses by gathering data are the foundation of science.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Are Children Too Overweight?*

Obesity is a serious problem. In every age group, from childhood to age 60, rates of obesity increase. Rates begin to decrease at about age 60, perhaps because some of the heaviest people die of the consequences of a lifetime of overweight—

The connection between overweight and disease was not always known. Since before written history, observers have noted that some children were heavier than others and that underweight children were more likely to die. That led to an assumption, still held by some adults: Heavy children are healthy (Laraway et al., 2010).

Sixty years ago another untested assumption was that heart attacks in older adults could not be prevented, or even predicted. Doctors were “baffled” and decided to study more than 5,000 adults in Framingham, Massachusetts, to see what they could learn (Levy & Brink, 2005).

The Framingham Heart Study began in 1948, collecting data and drawing conclusions that, by 1990, revolutionized adult behavior—

That research led to a new thought: Since obese adults are likely to die of heart attacks and strokes, childhood obesity might be a health risk, too. That thought (Step 1) led to the hypothesis (Step 2) that childhood overweight impairs adult health.

This hypothesis is now widely assumed to be true. For instance, a poll found that most Californians consider childhood obesity “very serious,” with a third of them rating poor eating habits as a worse risk to child health than drug use or violence (Hennessy-

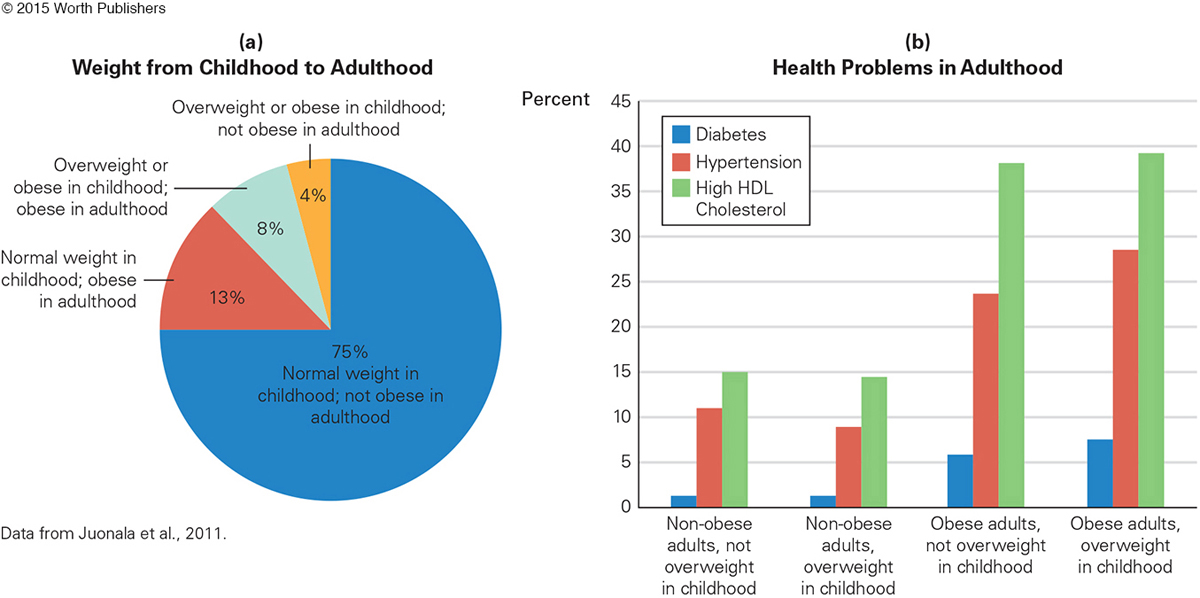

The best way to test that hypothesis (Step 3) is to examine adult health in people who had been weighed and measured in childhood. Several researchers did exactly that. Indeed, four studies measured and weighed children and then assessed the same people as adults. Most (83 percent) of the people in these studies maintained their relative weight (see Figure 1.2a).

From that research, a strong conclusion was reached (Step 4) and published (Step 5): Overweight and obese children are likely to become obese adults, who then are at high risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and early death (Juonala et al., 2011). For instance, in those four studies, 29 percent of those who were overweight from childhood on had high blood pressure as adults, compared to 11 percent of those who were never overweight.

A new question arose (Step 1), building on the earlier findings. What about overweight children who become normal-

Many other issues, complications, and conclusions regarding obesity are discussed later in this book. For now, all you need to remember are the steps of the scientific method and that developmentalists are right: Significant “change over time” is possible.

The Nature–Nurture Controversy

nature

In development, nature refers to the traits, capacities, and limitations that each individual inherits genetically from his or her parents at the moment of conception.

nurture

In development, nurture includes all the environmental influences that affect the individual after conception. This includes everything from the mother’s nutrition while pregnant to the cultural influences in the nation.

An easy example of the need for science concerns a great issue in development, the nature–

The nature–

Some people believe that most traits are inborn, that children are innately good (an “innocent child”) or bad (“beat the devil out of them”). Other people stress nurture, crediting or blaming parents, or neighborhoods, or society, or drugs.

Neither extreme is accurate. The question is “how much,” not “which,” because both genes and experience affect every characteristic: Nature always affects nurture, and then nurture affects nature.

Some scientists think that even “how much” is misleading: It implies that nature and nurture each contribute a fixed amount when actually their explosive interaction is crucial (Eagly & Wood, 2013; Lock, 2013).

epigenetics

The study of how environmental factors affect genes and genetic expression—

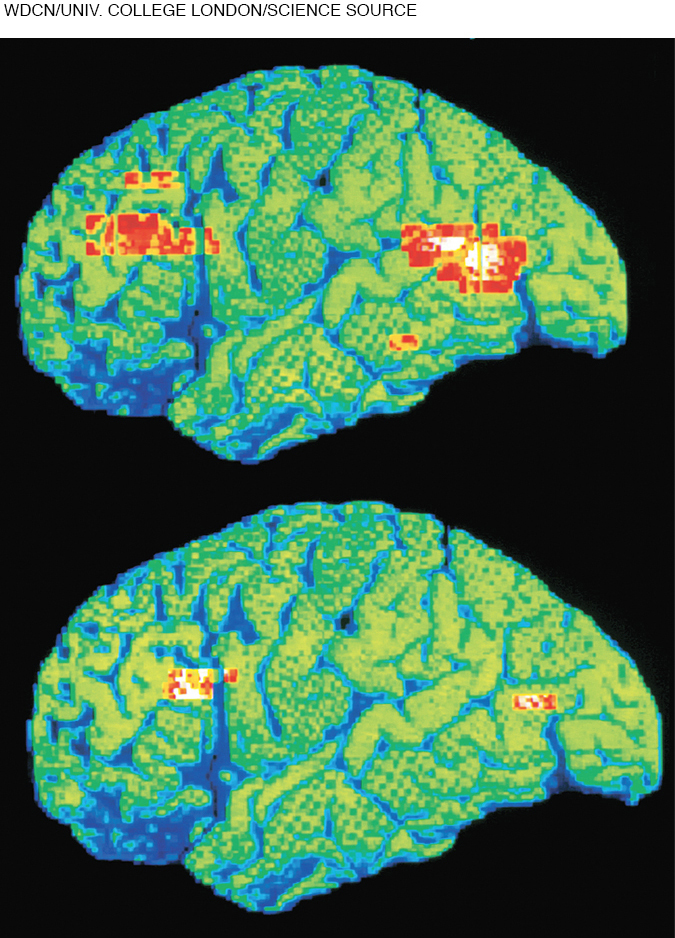

EPIGENETICS A new discipline related to genetics is called epigenetics—it explores the many ways environmental forces alter genetic expression. Neuroscientists have shown that loneliness, for example, can literally change structures in the brain (Cacioppo et al., 2014).

Sometimes protective factors, in either nature or nurture, outweigh liabilities. As one review explains, “there are, indeed, individuals whose genetics indicate exceptionally high risk of disease, yet they never show any signs of the disorder” (Friend & Schadt, 2014, p. 970). Why? Epigenetics.

differential susceptibility

The idea that people vary in how sensitive they are to particular experiences. Often such differences are genetic, which makes some people affected “for better or for worse” by life events. (Also called differential sensitivity.)

DANDELIONS AND ORCHIDS There is increasing evidence of differential susceptibility—that is, how sensitivity to any particular environmental experience differs from one person to another because of the particular genes each person has inherited.

Some people are like dandelions—hardy, growing and thriving in good soil or bad, with or without ample sun and rain. Other people are like orchids—quite wonderful, but only when ideal growing conditions are met (Ellis & Boyce, 2008; Laurent, 2014).

For example, in one study, depression in pregnant women was assessed and then the emotional maturity of their children was measured. Those children who had a particular version of the serotonin transporter gene (5-

The interaction between nature and nurture is apparent for every topic in this book, as you will see, and in every moment of our lives, as I see in myself. In retrospect, I fainted at Caleb’s birth because of the interaction of at least eight factors (low blood sugar, lack of sleep, physical exertion, gender, age, joy, memories, relief), all influenced by both nature and nurture, a combination that threw me to the floor.

The Three Domains

Obviously, it is impossible to examine nature and nurture in every aspect of human development at once, especially for any one individual. I do not know how much of my fainting was affected by my genes, nor how much by my past experiences.

A century ago, nature (especially physical development such as tooth eruption or running speed) was the main focus of developmental research. Scientists now realize that social factors affect every aspect of development and that intellect and emotions, not just physical growth, develop throughout the entire life span. All three are always responsive to each other.

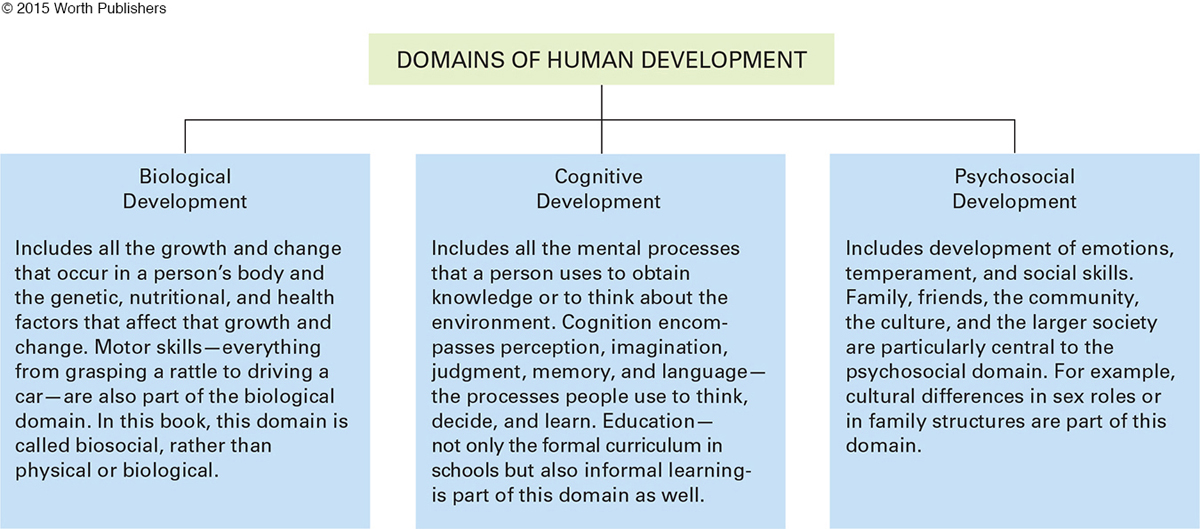

Consequently, the traditional emphasis on physical growth has been accompanied by recognition of cognition and social interactions. Development is often divided into three domains—

Each domain includes several academic disciplines: Biological includes physiology, neuroscience, and medicine; cognitive includes psychology, linguistics, and education; and psychosocial includes economics, sociology, and history.

Typically, each scientist pursues a particular thread within one discipline, using clues, research, and conclusions from scientists in other disciplines who have concentrated on that same thread. Yet always remember that the interaction between and among domains—

Since every individual is a tapestry of many-

From the recognition of the interaction of domains comes a related concept in psychology called embodied cognition, the idea that people’s thinking and social relationships are affected by their bodies. For instance, walking in a happy, open way makes a person feel happier, and standing arms akimbo makes a person feel confident and makes other people perceive that person as competent. More research is needed, as the evidence for embodied cognition is mixed, but no one doubts that all three domains interact (Marmolejo-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 1.1

1. What are the five steps of the scientific method?

(1) Pose a question; (2) develop a hypothesis; (3) test the hypothesis (usually by doing research); (4) draw conclusions; and (5) report the results.

Question 1.2

2. Why is replication important?

Replication confirms, modifies, or refutes the conclusions of a scientific study.

Question 1.3

3. What basic question is at the heart of the nature–

The basic question is: How much of any characteristic, behavior, or emotion is the result of genes, and how much is the result of experience?

Question 1.4

4. What is the difference between “genetics” and “epigenetics”?

The term “genetics” refers to the influence of genes. “Epigenetics” is a new discipline that explores the many ways environmental factors affect genes and genetic expression.

Question 1.5

5. How might differential susceptibility apply to understanding students’ varied responses to a low exam grade?

This concept applies here because it explains that people vary in how sensitive they are to particular experiences, depending on their genetic makeup. Some students might take a poor grade to mean that they are failures, while others shrug off the low grade and know to try harder next time.

Question 1.6

6. What are the three domains of development?

The three domains are biological, cognitive, and psychosocial.

Question 1.7

7. How does multidisciplinary research connect with the three domains?

The interaction between and among domains is essential to understanding the whole developing person. Every individual is a tapestry of many-