Why We Make Arguments

Why We Make Arguments

In the politically divided and entertainment-driven culture of the United States today, the word argument may well call up negative images: the hostile scowl or shaking fist of a politician or news “opinionator” who wants to drown out other voices and prevail at all costs. This winner-take-all view turns many citizens off to the whole process of using reasoned conversation to identify, explore, and solve problems. Hoping to avoid personal conflict, many people now sidestep opportunities to speak their mind on issues shaping their lives and work. We want to counter this attitude throughout this book.

Some arguments, of course, are aimed at winning, especially those related to politics, business, and law. Two candidates for office, for example, vie for a majority of votes; the makers of one smartphone try to outsell their competitors by offering more features at a lower price; and two lawyers try to outwit each other in pleading to a judge and jury. In your college writing, you may also be called on to make arguments that appeal to a “judge” and “jury” (perhaps your instructor and classmates). You might, for instance, argue that students in every field should be required to engage in service learning projects. In doing so, you will need to offer better arguments or more convincing evidence than potential opponents — such as those who might regard service learning as a politicized or coercive form of education. You can do so reasonably and responsibly, no name-calling required.

There are many reasons to argue and principled ways to do so. We explore some of them in this section.

In the excerpt from his book Disability and the Media: Prescriptions for Change, Charles A. Riley II intends to convince other journalists to adopt a less stereotypical language for discussing diversity.

Arguments to Convince and Inform

We’re stepping into an argument ourselves in drawing what we hope is a useful distinction between convincing and — in the next section — persuading. (Feel free to disagree with us.) Arguments to convince lead audiences to accept a claim as true or reasonable — based on information or evidence that seems factual and reliable; arguments to persuade then seek to move people beyond conviction to action. Academic arguments often combine both elements.

Many news reports and analyses, white papers, and academic articles aim to convince audiences by broadening what they know about a subject. Such fact-based arguments might have no motives beyond laying out what the facts are. Here’s an opening paragraph from a 2014 news story by Anahad O’Connor in the New York Times that itself launched a thousand arguments (and lots of huzzahs) simply by reporting the results of a recent scientific study:

Many of us have long been told that saturated fat, the type found in meat, butter and cheese, causes heart disease. But a large and exhaustive new analysis by a team of international scientists found no evidence that eating saturated fat increased heart attacks and other cardiac events.

— Anahad O’Connor, “Study Questions Fat and Heart Disease Link”

Wow. You can imagine how carefully the reporter walked through the scientific data, knowing how this new information might be understood and repurposed by his readers.

Similarly, in a college paper on viability of nuclear power as an alternative source of energy, you might compare the health and safety record of a nuclear plant to that of other forms of energy. Depending upon your findings and your interpretation of the data, the result of your fact-based presentation might be to raise or alleviate concerns readers have about nuclear energy. Of course, your decision to write the argument might be driven by your conviction that nuclear power is much safer than most people believe.

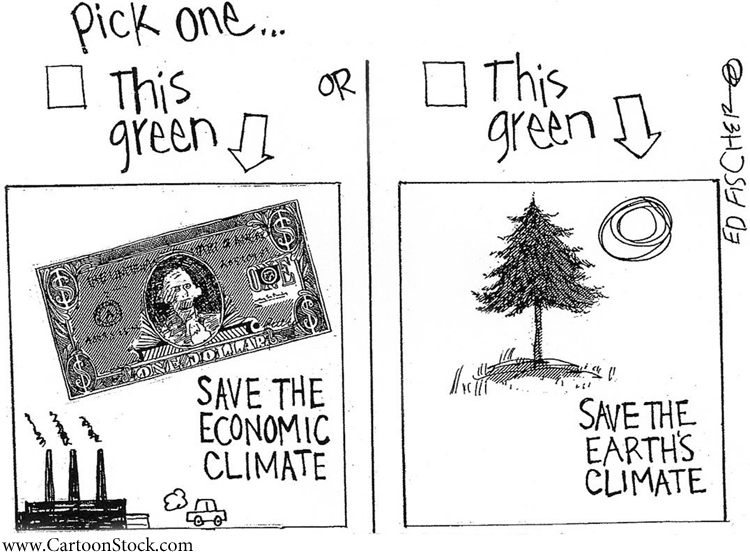

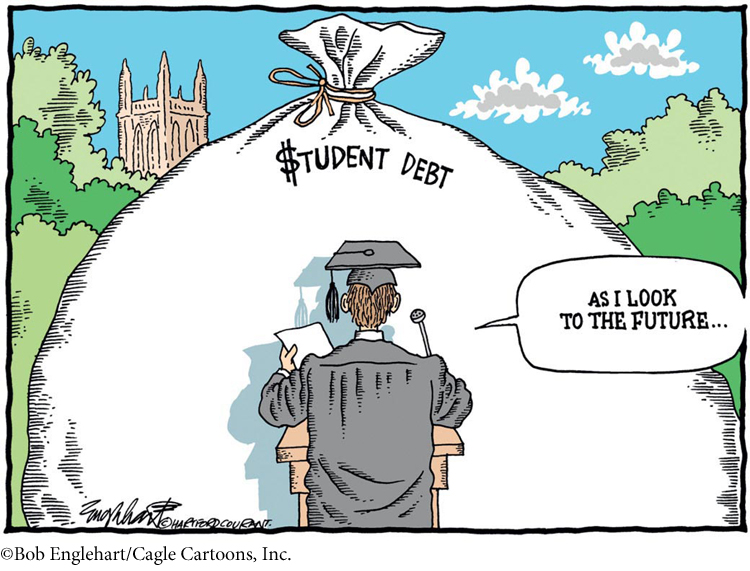

Even an image can offer an argument designed both to inform and to convince. Below, for example, editorial cartoonist Bob Englehart finds a way to frame an issue on the minds of many students today, the burden of crushing debt. As Englehart presents it, the problem is impossible to ignore.

Arguments to Persuade

Today, climate change may be the public issue that best illustrates the chasm that sometimes separates conviction from persuasion. The weight of scientific research may convince people that the earth is warming, but persuading them to act on that knowledge doesn’t follow easily. How then does change occur? Some theorists suggest that persuasion — understood as moving people to do more than nod in agreement — is best achieved via appeals to emotions such as fear, anger, envy, pride, sympathy, or hope. We think that’s an oversimplification. The fact is that persuasive arguments, whether in advertisements, political blogs, YouTube videos, or newspaper editorials, draw upon all the appeals of rhetoric (see “Appealing to Audiences” in Chapter 1, “Everything's an Argument”) to motivate people to act — whether it be to buy a product, pull a lever for a candidate, or volunteer for a civic organization. Here, once again, is Camille Paglia driving home her argument that the 1984 federal law raising the drinking age in the United States to 21 was a catastrophic decision in need of reversal:

What this cruel 1984 law did is deprive young people of safe spaces where they could happily drink cheap beer, socialize, chat, and flirt in a free but controlled public environment. Hence in the 1980s we immediately got the scourge of crude binge drinking at campus fraternity keg parties, cut off from the adult world. Women in that boorish free-for-all were suddenly fighting off date rape. Club drugs — Ecstasy, methamphetamine, ketamine (a veterinary tranquilizer) — surged at raves for teenagers and on the gay male circuit scene.

Paglia chooses to dramatize her argument by sharply contrasting a safer, more supportive past with a vastly more dangerous present when drinking was forced underground and young people turned to highly risky behaviors. She doesn’t hesitate to name them either: binge drinking, club drugs, raves, and, most seriously, date rape. This highly rhetorical, one might say emotional, argument pushes readers hard to endorse a call for serious action — the repeal of the current drinking age law.

RESPOND •

Apply the distinction made here between convincing and persuading to the way people respond to two or three current political or social issues. Is there a useful distinction between being convinced and being persuaded? Explain your position.

Arguments to Make Decisions

Closely allied to arguments to convince and persuade are arguments to examine the options in important matters, both civil and personal — from managing out-of-control deficits to choosing careers. Arguments to make decisions occur all the time in the public arena, where they are often slow to evolve, caught up in electoral or legal squabbles, and yet driven by a genuine desire to find consensus. In recent years, for instance, Americans have argued hard to make decisions about health care, the civil rights of same-sex couples, and the status of more than 11 million immigrants in the country. Subjects so complex aren’t debated in straight lines. They get haggled over in every imaginable medium by thousands of writers, politicians, and ordinary citizens working alone or via political organizations to have their ideas considered.

For college students, choosing a major can be an especially momentous personal decision, and one way to go about making that decision is to argue your way through several alternatives. By the time you’ve explored the pros and cons of each alternative, you should be a little closer to a reasonable and defensible decision.

Sometimes decisions, however, are not so easy to make.

Arguments to Understand and Explore

Arguments to make decisions often begin as choices between opposing positions already set in stone. But is it possible to examine important issues in more open-ended ways? Many situations, again in civil or personal arenas, seem to call for arguments that genuinely explore possibilities without constraints or prejudices. If there’s an “opponent” in such situations at all (often there is not), it’s likely to be the status quo or a current trend which, for one reason or another, puzzles just about everyone. For example, in trying to sort through the extraordinary complexities of the 2011 budget debate, philosophy professor Gary Gutting was able to show how two distinguished economists — John Taylor and Paul Krugman — draw completely different conclusions from the exact same sets of facts. Exploring how such a thing could occur led Gutting to conclude that the two economists were arguing from the same facts, all right, but that they did not have all the facts possible. Those missing or unknown facts allowed them to fill in the blanks as they could, thus leading them to different conclusions. By discovering the source of a paradox, Gutting potentially opened new avenues for understanding.

The infographic “Speak My Language” by Santos Henarejos explores how technology has affected the way we communicate around the world.

Exploratory arguments can also be personal, such as Zora Neale Hurston’s ironic exploration of racism and of her own identity in the essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me.” If you keep a journal or blog, you have no doubt found yourself making arguments to explore issues near and dear to you. Perhaps the essential argument in any such piece is the writer’s realization that a problem exists — and that the writer or reader needs to understand it and respond constructively to it if possible.

Explorations of ideas that begin by trying to understand another’s perspective have been described as invitational arguments by researchers Sonja Foss, Cindy Griffin, and Josina Makau. Such arguments are interested in inviting others to join in mutual explorations of ideas based on discovery and respect. Another kind of argument, called Rogerian argument (after psychotherapist Carl Rogers), approaches audiences in similarly nonthreatening ways, finding common ground and establishing trust among those who disagree about issues. Writers who take a Rogerian approach try to see where the other person is coming from, looking for “both/and” or “win/win” solutions whenever possible. (For more on Rogerian strategies, see Chapter 7.)

RESPOND •

What are your reasons for making arguments? Keep notes for two days about every single argument you make, using our broad definition to guide you. Then identify your reasons: How many times did you aim to convince? To inform? To persuade? To explore? To understand?