Scheduling

The notion of any schedule is based on specific needs and goals, and is designed to permit you to move through your tasks as quickly and efficiently as possible. However, when it comes to making a movie, the schedule is the yin to the budget’s yang; you can’t design a reasonable budget until you have first created a logistically feasible schedule. And if you don’t have a schedule and a budget, you can’t make your movie—

This means that after finding a story and developing a script that you like, one of the first things you must do is sit down and break your script apart—

Once you have broken down the script, you will build a preliminary shooting schedule, which is essentially the plan for shooting particular scenes on particular days in particular places with particular people and in a particular order until you have the material you need to go into postproduction and edit it all together into a movie. Not only will you need to prepare the shooting schedule with backup scenarios and alternative options in mind, but you will need to take the time to analyze the schedule you have created and revise it multiple times before heading out and shooting anything.

Script Breakdown

In some respects, breaking down the script is similar to the art of marking up your script, as discussed in Chapter 3. In other ways it resembles how you or a department head concerned with one particular area of the production would analyze the script, as described in Chapter 4. Here, however, your job is global, not local, so to speak—

Therefore, the overall script breakdown involves a series of formal steps in which you go through the script and identify key elements for each shot or scene. Key elements are, in essence, every person, place, or thing that you will need to schedule or otherwise allocate resources to in order to have them available and ready to go on your designated shooting day. Knowing these things, in turn, will help you ascertain how many shooting days you will likely need. Once you have this information, you can calculate what money and other resources you will need to spend, which will allow you to determine if your schedule is in fact feasible given your resources and timeline for completing the project. If it isn’t, you will at least have a working foundation for scaling it back.

If, for example, you know you only have a 10-

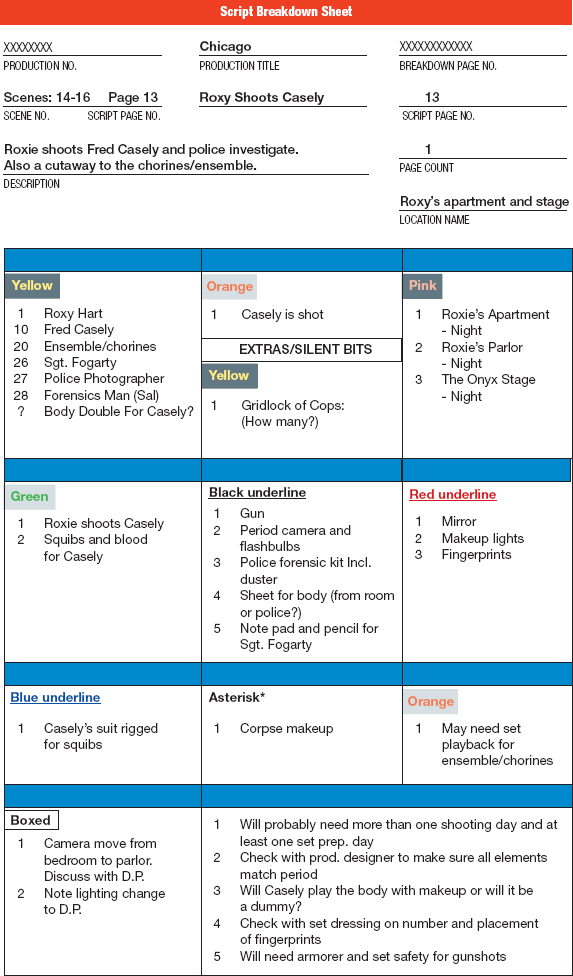

How a breakdown sheet might look, in this case using Chicago (2002) as an example

Line the script. For this step, you literally mark up a physical script, or use specialized scheduling software, to call out key elements you will need to account for in your schedule: locations, actors, extras, vehicles, animals, makeup, props, costumes, visual effects, and so on. Pay attention to script notes about time of day and setting, and instructions about whether scenes must be interior (INT) or exterior (EXT)—and notice that we used the word must. As you go through the script, you need to calculate places where you might be able to change an interior to an exterior, night to day, or vice versa, in order to make the best use of your limited shooting days. Maintain the script instruction when the story needs you to, but when there is wiggle room, decide what is best for the schedule and resources and base your decision on those factors. Along the way, as we discuss in Chapter 4, these notations will indicate where and when you think a stage can replace a location, when one location can double for two or more locations, when you can use a visual effect or a simple camera or an optical technique to avoid a location or complicated set, and so on. This kind of thinking is crucial in schedule building.

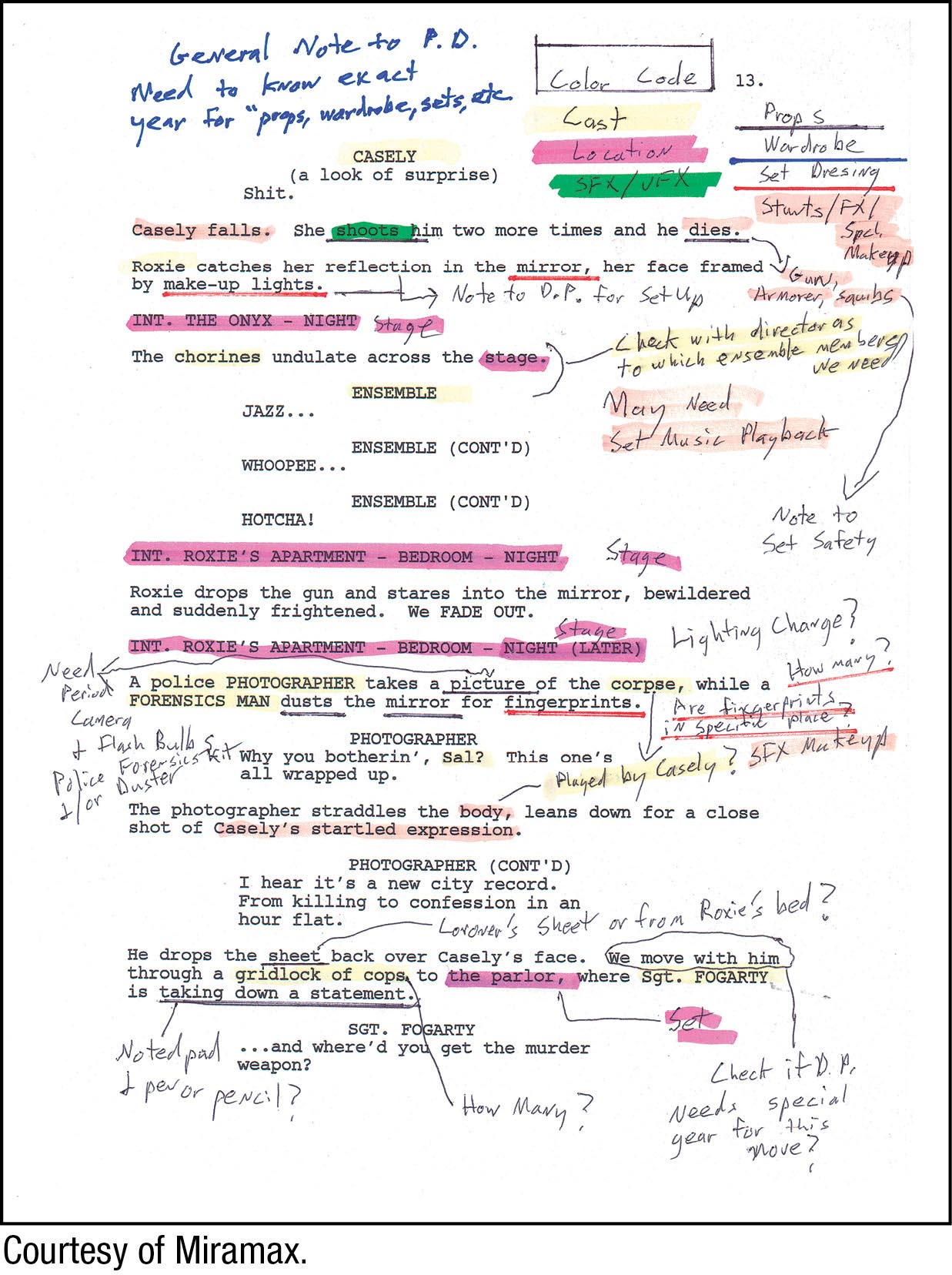

Line the script. For this step, you literally mark up a physical script, or use specialized scheduling software, to call out key elements you will need to account for in your schedule: locations, actors, extras, vehicles, animals, makeup, props, costumes, visual effects, and so on. Pay attention to script notes about time of day and setting, and instructions about whether scenes must be interior (INT) or exterior (EXT)—and notice that we used the word must. As you go through the script, you need to calculate places where you might be able to change an interior to an exterior, night to day, or vice versa, in order to make the best use of your limited shooting days. Maintain the script instruction when the story needs you to, but when there is wiggle room, decide what is best for the schedule and resources and base your decision on those factors. Along the way, as we discuss in Chapter 4, these notations will indicate where and when you think a stage can replace a location, when one location can double for two or more locations, when you can use a visual effect or a simple camera or an optical technique to avoid a location or complicated set, and so on. This kind of thinking is crucial in schedule building. Fill-

Fill-in breakdown sheets. Transfer the information you have broken out when you lined the script on a scene-by- scene basis to individual breakdown sheets, representing each scene in the movie. A professional breakdown sheet (such as the one here) features spreadsheet- style category boxes for each element, so that the data you port over from elements you flagged when you lined the script will ideally flow into appropriate categories— “cars” will end up listed under “vehicles,” and “guns” will end up under “props,” and so on. Depending on the software you use and your degree of sophistication, you can assign unique numbers for characters, scenes, props, and locations and then cross- reference them to make it easy for you to find elements and determine the frequency with which they appear in the story as you set out to budget for them. This provides you with the equivalent of a database that delineates elements for every scene, which you will need to take into consideration when creating a schedule. Once you have breakdown sheets for every scene, you can easily calculate how many elements different scenes share in common, so that when you are ready to build your shooting schedule, you can make plans to shoot similar pieces of different scenes involving the same location, actors, props, or other elements at the same time, to make the best use of your resources. To be most efficient, assign headers to each breakdown sheet that include, at a minimum, the script page; the scene number or name; the number of pages; the location; and whether it is a day, night, interior, or exterior scene.

Create lists or boards. This step involves sorting the information on the breakdown sheets to provide a visual representation of the different categories of elements so that an actual shooting schedule can begin to take shape. In the pre-

Create lists or boards. This step involves sorting the information on the breakdown sheets to provide a visual representation of the different categories of elements so that an actual shooting schedule can begin to take shape. In the pre-digital era, this tool was known as the production board: a graphical display of breakdown- sheet information on a series of thin, color- coded cardboard charts, often called production strips, that the production manager would manually sort and mount on a large production board for the entire production management team to see and use, moving the strips around to form a rudimentary schedule. In some low- budget situations, independent filmmakers have even been known to use index cards. Today, scheduling software, such as affordable tools like Movie Magic Scheduling, have largely replaced physical boards or strips, but the idea is the same— to identify and arrange elements in such a way as to be able to build a shooting schedule. One of the beneficial things about today’s online world is that you can easily create and inexpensively share simple spreadsheets and other documents online using Google Docs and other similar tools. Out of your breakdown sheets, especially if you use the right spreadsheet or scheduling software, it is fairly easy to sort and generate accurate and handy lists of related items, typically sorted in order of their expected cost. On professional productions, the most important lists are typically people and locations, since movie stars usually eat up the most money, and the availability of locations can frequently impact many aspects of your entire schedule. As a student filmmaker, you can evaluate which list will be most crucial and compile your lists according to your priorities. In any case, you will typically generate prop lists, wardrobe lists, vehicle lists, equipment lists, and other specialized lists, such as a list of visual or practical effects. These lists can be as detailed as you want or need them to be, and are a handy tool to help you both budget for particular items and, later, keep track of, and procure, those items. Essentially, you will be sorting out lists based on your project’s needs. In a student production, virtually everyone will likely be volunteering his or her time. Therefore, although they might not be costing you much money, figuring out whom you will need—

cast, crew, and support— and when, will be your biggest scheduling challenge. After all, in addition to scheduling around your project’s needs, you will need to schedule around your cast and crew’s limited availability, as well.

This page of the script for Chicago (previously seen in Chapter 3) has been marked up with the kind of notes a production manager might use to keep track of various elements of the production.

Shooting Schedule

There is no way around the fact that creating a shooting schedule is an art that takes time and experience to learn how to do skillfully. As we have already cautioned, a wide range of factors can impact it and force you to change it, often on the fly, requiring you to make as many contingency plans as possible when creating the schedule, as we will examine below. But if you boil things down, your basic goals for scheduling are as follows:

Schedule so that you can capture what you absolutely must capture to complete your movie. Note that this is a far different thing than capturing everything you might want to capture. In other words: prioritize and make hard and often difficult choices along the way.

Schedule so that you can capture what you absolutely must capture to complete your movie. Note that this is a far different thing than capturing everything you might want to capture. In other words: prioritize and make hard and often difficult choices along the way. Be as efficient and flexible as possible.

Be as efficient and flexible as possible. Be as realistic as possible—don’t attempt things that simply lie outside your resource capabilities.

Be as realistic as possible—don’t attempt things that simply lie outside your resource capabilities. Always prepare as many backup options as you possibly can (see Action Steps: Be Prepared, below).

Always prepare as many backup options as you possibly can (see Action Steps: Be Prepared, below).

ACTION STEPS

Be Prepared

When scheduling a shoot, consider different scenarios and build various options into your schedule as backup plans should conditions require you to suddenly shift gears. Seasoned filmmakers recommend thinking about the following as you put your schedule together:

Make sure any permits or releases have been identified and taken care of long before your shooting day. Film history is littered with stories of shoots held up by union violations, fire or safety violations, or people showing up where they don’t have permission to be. Have all paperwork in order before you go anywhere.

Make sure any permits or releases have been identified and taken care of long before your shooting day. Film history is littered with stories of shoots held up by union violations, fire or safety violations, or people showing up where they don’t have permission to be. Have all paperwork in order before you go anywhere. Constantly analyze weather’s potential impact on each of your exterior locations and schedule, or at least make notes about what you would do on shooting days at those locations if you were rained out. Monitor the weather and stay in communication with your cast and crew, so that you can give them as much advance warning as possible if the time or location or scene to be shot the next morning will need to change.

Constantly analyze weather’s potential impact on each of your exterior locations and schedule, or at least make notes about what you would do on shooting days at those locations if you were rained out. Monitor the weather and stay in communication with your cast and crew, so that you can give them as much advance warning as possible if the time or location or scene to be shot the next morning will need to change. When feasible, arrange for what is known as a cover set—an accessible interior or covered location that you keep available to shoot at in the event bad weather or something else cancels shooting at an exterior location. Keep in mind that a cover set could be set up in a garage, a basement, your home, or in a location near your exterior location.

When feasible, arrange for what is known as a cover set—an accessible interior or covered location that you keep available to shoot at in the event bad weather or something else cancels shooting at an exterior location. Keep in mind that a cover set could be set up in a garage, a basement, your home, or in a location near your exterior location. If at all possible, schedule weather-dependent exterior shooting days early in your shooting schedule, so that if you do get rained out, you might have time to return there, or at least to get exterior shots to combine with material you captured at your cover set.

If at all possible, schedule weather-dependent exterior shooting days early in your shooting schedule, so that if you do get rained out, you might have time to return there, or at least to get exterior shots to combine with material you captured at your cover set. When scouting or arranging permission to shoot in a particular location, such as a restaurant, talk to your contact about an alternative day and time, beyond the agreed-upon day and time, when it might be permissible for your team to show up with minimal notice. If you run into an exterior day ruined by weather and know you have permission to be in the restaurant that same day, you can save an entire day of shooting, but you won’t know that if you haven’t had that conversation well in advance.

When scouting or arranging permission to shoot in a particular location, such as a restaurant, talk to your contact about an alternative day and time, beyond the agreed-upon day and time, when it might be permissible for your team to show up with minimal notice. If you run into an exterior day ruined by weather and know you have permission to be in the restaurant that same day, you can save an entire day of shooting, but you won’t know that if you haven’t had that conversation well in advance.

TRIM YOUR SHOOTING SCRIPT

TRIM YOUR SHOOTING SCRIPT

Continually and dispassionately examine your script and schedule for scenes and shots you think your movie can live without—material that may be pretty or interesting, but that does not have a significant influence on your narrative. Schedule shooting for that material last, and cut it out if you fall behind schedule or need to switch to something else on a particular shooting day.

As you sort your strips or use your scheduling software, you need to plan what you calculate, not only the time it will take to shoot each scene but also the time it will take to set up and shoot on-set and, if necessary, to move from set to set or location to location. Obviously, you won’t know precisely how long it will take to get each shot, capture each sequence, or finish each scene until you actually do it, because it will depend on how many takes and how much coverage you end up pursuing; how your equipment, cast, and crew perform; how well communication works on your set; what unforeseen circumstances you encounter; and how you deal with such things. However, as noted in Chapter 2, each page of a final, locked screenplay typically equates to about one minute of screen time; thus, roughly one-quarter of a script page is going to take up about 15 seconds of screen time. Therefore, in most cases, it won’t be terribly efficient for you to spend an entire shooting day on a quarter page of your screenplay.

What does make sense is to plan your easiest-to-shoot scenes first, as a practical way to get your cast, crew, and sets ready before you segue into more complicated work later in the week. It’s not unusual to schedule a day to prep a set and then shoot two or three quick scenes on the set on one day, and then schedule several rigorous pages to be shot on that same set the next day. The set will be prepped and ready on day two, and thus there is a natural progression between these two shooting days.

In fact, on low-budget films, you may shoot three or four pages over the course of 10 or 12 hours.2 Generally, your pace is a function of your resources. The more money and time you have, the more deliberate you can afford to be. If you only have the luxury of a single day on a location, then logically everything your script says should be filmed in that location needs to be scheduled for that particular day. If all of those scenes won’t fit into that one day, and there is no possibility of rearranging the schedule for returning there, then obviously you will need to cut something out. Therefore, your scheduled shot list should be a priority list, ranging from what is most important to what is least important, and not just in terms of shots but also in terms of coverage (see Chapter 3). Decide when you can live with one angle or less coverage or fewer takes and move on.

KEEP YOUR FILES

KEEP YOUR FILES

Even when your project is finished, organize and file away any important documents connected to it. If an injury or a legal dispute ever occurs related to the project, your records could prove useful. Therefore, it is always important, even on a small student film, to have an efficient record-keeping system during production, and a smart filing and archiving system afterward. On a studio project, you will be required to turn such documentation over to the studio on completion.

Here are some other logical guidelines to keep in mind when preparing your schedule and determining how to order your shoot:

If your project’s schedule allows formal rehearsal days during production, schedule them at the beginning of the week and start shooting on Wednesday, so that everyone comes into the first day of shooting fully prepared, and you leave yourself the following weekend to make changes if they are required.

If your project’s schedule allows formal rehearsal days during production, schedule them at the beginning of the week and start shooting on Wednesday, so that everyone comes into the first day of shooting fully prepared, and you leave yourself the following weekend to make changes if they are required. It is rarely a good idea to film your movie in linear script order, particularly at the low-budget level. You need to schedule your shoots around access to your locations, actors, and other resources; you can put it all together in the editing phase.

It is rarely a good idea to film your movie in linear script order, particularly at the low-budget level. You need to schedule your shoots around access to your locations, actors, and other resources; you can put it all together in the editing phase. If particular actors are only available on certain days, use your scheduling software to print out what is called a day-out-of-days schedule for that individual, and try to select days when you can shoot all material involving that actor, even if it is from different scenes.

If particular actors are only available on certain days, use your scheduling software to print out what is called a day-out-of-days schedule for that individual, and try to select days when you can shoot all material involving that actor, even if it is from different scenes. We suggested in Chapter 4 that there are many advantages to shooting in places you have access to. Among these advantages is the possibility of increased scheduling flexibility. If you have a family member or dear friend with a house on the beach that they will permit you to use, change scenes that take place in the country to the beach unless there is a strong creative reason that would prevent it. For student films in particular, much of a typical story can be told by shooting in places you already have access to and are quite familiar with. Working in places you know, or in places you have been given access to by people you know, will frequently mean you can get more time there, or at least be able to work more efficiently there, thus adding more options to your schedule.

We suggested in Chapter 4 that there are many advantages to shooting in places you have access to. Among these advantages is the possibility of increased scheduling flexibility. If you have a family member or dear friend with a house on the beach that they will permit you to use, change scenes that take place in the country to the beach unless there is a strong creative reason that would prevent it. For student films in particular, much of a typical story can be told by shooting in places you already have access to and are quite familiar with. Working in places you know, or in places you have been given access to by people you know, will frequently mean you can get more time there, or at least be able to work more efficiently there, thus adding more options to your schedule. Schedule as much of the shoot to take place in one location, or in locations close to each other, as possible. The fewer moves there are between locations, the shorter time shooting will take, and the more you will be able to accomplish. If you have found a great old mansion in the country to shoot at, try to arrange to use the yard or surrounding grounds for your exterior work.

Schedule as much of the shoot to take place in one location, or in locations close to each other, as possible. The fewer moves there are between locations, the shorter time shooting will take, and the more you will be able to accomplish. If you have found a great old mansion in the country to shoot at, try to arrange to use the yard or surrounding grounds for your exterior work. Apply what you learned during location scouting (see Chapter 4). Learn everything you possibly can about where you are going and what typically goes on there at the time of day you will be there. For instance, if you have permission to shoot in the bleachers at a high school football field, and the bleachers are adjacent to a parking lot, know what time the parking lot starts filling up with noisy cars. If people start arriving at 9 a.m., schedule filming on the bleachers first thing, at 8 a.m., so that you can have a quieter environment and better sound for that scene before you move on to your scenes on the football field.

Apply what you learned during location scouting (see Chapter 4). Learn everything you possibly can about where you are going and what typically goes on there at the time of day you will be there. For instance, if you have permission to shoot in the bleachers at a high school football field, and the bleachers are adjacent to a parking lot, know what time the parking lot starts filling up with noisy cars. If people start arriving at 9 a.m., schedule filming on the bleachers first thing, at 8 a.m., so that you can have a quieter environment and better sound for that scene before you move on to your scenes on the football field. Any time you can combine tasks, you will be ahead of the game. Be alert to identifying days when you can kill two birds with one stone, so to speak—shooting scenes you had initially pondered taking care of later in your schedule because you will have extra cameras available for other scenes on different days, or will already be at a comparable location. Plan sequences to be captured on particular days based on logistics and feasibility.

Any time you can combine tasks, you will be ahead of the game. Be alert to identifying days when you can kill two birds with one stone, so to speak—shooting scenes you had initially pondered taking care of later in your schedule because you will have extra cameras available for other scenes on different days, or will already be at a comparable location. Plan sequences to be captured on particular days based on logistics and feasibility. Have a list of alternative shots or sequences or establishing material you could shoot at the same location, or other tasks you could take care of, if setup for a particularly complicated scene is taking too long—things you can get done while you are waiting to get other things done.

Have a list of alternative shots or sequences or establishing material you could shoot at the same location, or other tasks you could take care of, if setup for a particularly complicated scene is taking too long—things you can get done while you are waiting to get other things done.

CREATING A BACKUP PLAN

CREATING A BACKUP PLAN

Create two schedules for shooting what is supposed to be an exterior scene in your student film: one, the basic plan; and the other, the backup plan. Describe the scene, actors and crew needed, and location, and type up a simple morning shooting schedule. Then, presume there is a good possibility of rain that morning. Come up with a new schedule and plan for the same sequence. Will you have a cover set prepared? (If so, describe the details.) Will there be an available interior near the original exterior location and a creative way to move the scene inside and still make it work? Will you have an alternate scene that could be shot in the rain? Explain your plan, schedule, and justification for your decisions.

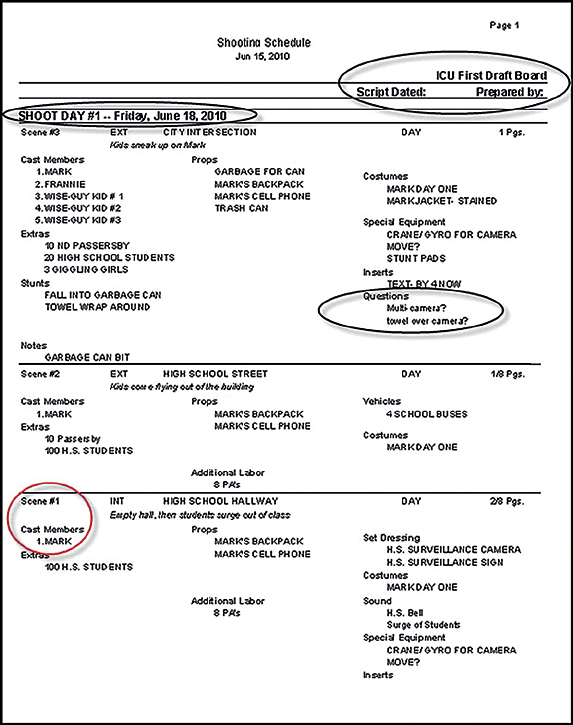

FIGURE 5.1

In this example of a shooting schedule, you will see that many elements are specifically enumerated, including actors, props, costumes, and set dressing.

The shooting schedule will ultimately be used to generate the daily call sheet, a document that delineates each shooting day’s operational plan in detail, informing everyone involved where they are supposed to be and when; what equipment, costumes, or props will be needed; what scenes will be shot, and in what order; and so forth (see Figure 5.1). Additionally, a typical call sheet will list important ancillary information, like what the day’s weather is expected to be like, parking information, emergency cell-phone numbers, meal times or options, and hospital or doctor information. Often, the first assistant director is responsible for generating each day’s call sheet, subject to the producer’s and the director’s approval. Today, making call sheets is a relatively easy and inexpensive thing to do, thanks to several types of online and mobile apps now available, including Doddle, Pocket Call Sheet, and Shot Lister.3