10.5 The Problem with Plastic

Assess the environmental impact of and remedies for plastic pollution in the oceans.

Plastic is cheaper than most natural materials, and it often performs better. Nearly everything we use is composed at least partly of plastic: electronics (cell phones and computers), packaging, facial scrubs, toothbrushes, credit cards, bags, bottles, car parts, combs and hairbrushes, clothing—

Each year, about 300 million metric tons of plastic are made. That is about 42 kg (92 lb) per year for each person on Earth.

More plastic has been made in the last 10 years than in all of the previous 100 years.

Only about 5%–10% of all plastic made is recycled.

Most plastic is not biodegradable (it cannot be broken down by decomposers). About 40% of plastic is disposed of in landfills, and the rest is either still in use or litters the continents and oceans.

What Happens to Plastic in the Oceans?

How does plastic get into the oceans? Most of the plastic entering the oceans comes from streams flowing into the sea and from beaches. Plastic trash in the streets of towns and cities is washed into storm drains, then into rivers, then into the oceans.

About 70% of all plastic that enters the oceans eventually sinks to the seafloor. There it is swept away by deep-

Question 10.10

What is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch?

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a concentration of plastic that has entered the ocean through storm drains and rivers in urban areas and collected in the North Pacific Gyre.

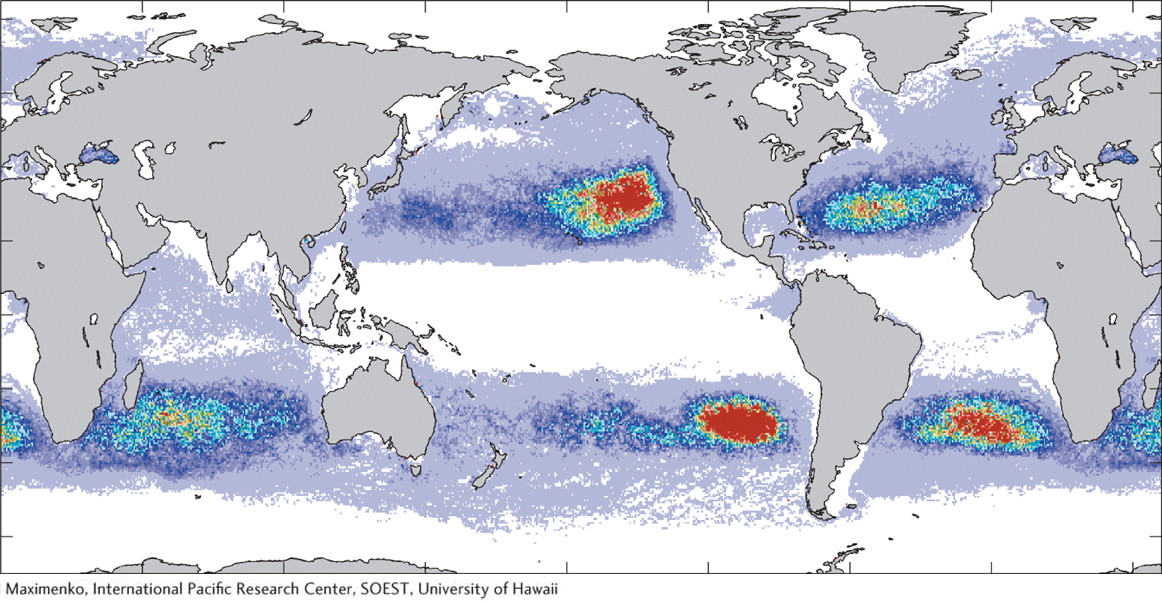

The 30% of plastic that remains suspended in the sunlit epipelagic zone is carried on the ocean gyres. Eventually, that plastic collects in the center of the gyre in what is often referred to as a garbage patch or plastic vortex. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a region of concentrated plastic litter formed by the North Pacific Gyre, is the largest and best known of these collections. It is made up of an estimated 100 million metric tons of plastic trash. This suspended plastic ranges in size from massive clumps of fishing nets to minuscule bits of plastic invisible to the human eye. Most of the pieces are less than 1 cm (0.4 in) in length and cannot be seen from a boat. Towing a fine sieve (net) through the water catches them (Figure 10.34).

Great Pacific Garbage Patch

A region of concentrated plastic litter formed by the North Pacific Gyre.

The plastic in garbage patches is undetectable to satellites because most of it is suspended just beneath the water surface. Yet ocean current patterns are well known, and computer simulations reveal where the plastic collects, as shown in Figure 10.35.

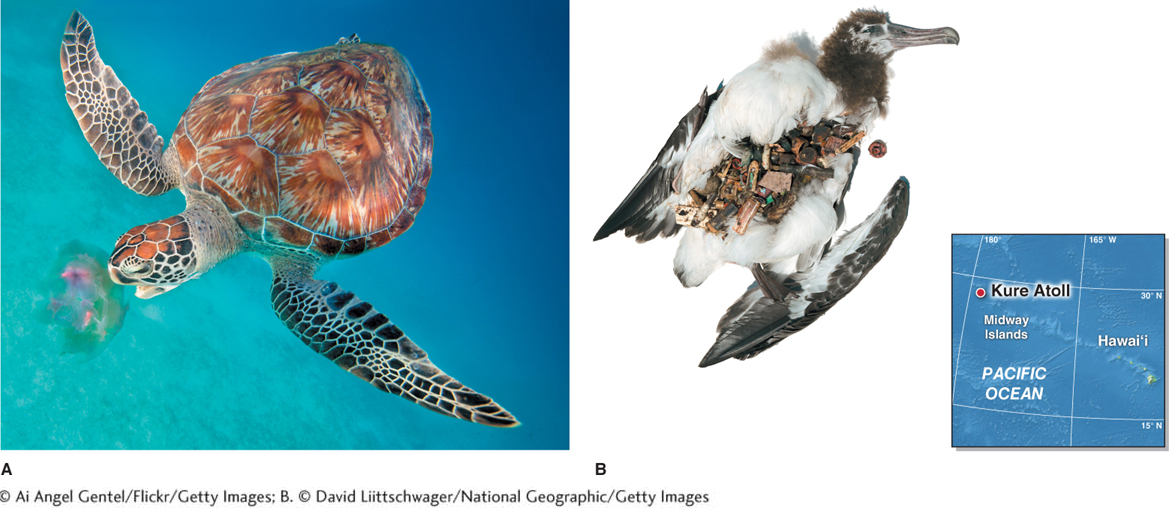

Transported by ocean currents, suspended plastic finds its way to the most remote areas. There, waves wash it onto beaches, where it collects and breaks down further (Figure 10.36).

How Does Plastic in the Oceans Pose a Problem?

Suspended plastic provides a surface onto which many forms of life cling, creating what's called the plastisphere. Some of this life can be harmful. For example, bacteria in the genus Vibrio, which cause cholera and other human health ailments, have been found on ocean plastic. Researchers suspect that such pathogens are able to persist longer and travel farther as they cling to plastic particles adrift in the ocean.

Suspended plastic particles in the oceans also attract and adsorb (bind to their surface) toxic chemicals that have entered ocean waters (such as PCBs and DDEs from industrial activity and pesticides from agricultural spraying). Plastics have been found to carry concentrations of PCBs and DDEs 1 million times those of seawater. The toxins may then enter organisms that eat the plastic. Scientists have documented ingestion of microscopic bits of plastic by organisms such as barnacles, krill (small shrimplike organisms), and fish that filter-

Plastic does more obvious harm to marine life when animals eat it or become entangled in it (Figure 10.37). Scientists estimate that 100,000 marine mammals and sea turtles are killed by plastic each year, mostly through entanglement.

Plastic debris is not limited to the oceans. In 2012, scientists found that the Great Lakes contain high concentrations of microscopic plastic particles. Most of them come from facial cleansers that contain tiny plastic beads.

Fixing the Problem

The problem with plastic in the oceans resembles other situations in which a pollutant released into the environment by people has led to problems in Earth’s physical and biological systems later on. Toxic air pollutants (Section 1.4), CFCs in the ozonosphere (Section 1.5), and carbon in the atmosphere (Section 6.3) are three examples we have examined in this book.

As of 2014, a cumulative total of 29 billion metric tons of plastic had been made. At this rate, by the middle of this century, a total of roughly 40 billion metric tons of plastic will have been made, mostly in the United States, Europe, and China. There is too much plastic being made to clean it up after it has entered the environment, and doing away with plastic altogether is not practical.

What can society do? There is no single solution. An important step toward addressing this problem is making the problem widely known. As Figure 10.38 demonstrates, a social media campaign to inform the public is under way.

What can an individual do? Reduce, reuse, and recycle. Many of the plastic items that enter the oceans are designed to be one-

To address this issue, closed-

Another important step is to create plastics that biodegrade in the environment. Biodegradable vegetable-

Modern society needs plastic, and it needs healthy ecosystems. The two need not be mutually incompatible. The way plastic is perceived and manufactured will certainly change as more people become aware of this growing ecological problem.