10.3 Is Prejudice an Ugly Thing of the Past?

The historical record shows that prejudice has been rampant in the past. But what about now? If we look around the world, surely we would conclude it’s not just an ugly aspect of history. Prejudice based on ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation continues to fuel violence and societal turmoil in many parts of the world. But what about in the United States? In the 21st century, aren’t Americans past all of that? Isn’t America a land of truly equal opportunity?

Although many European Americans believe that racial prejudice is a thing of the past (Norton & Sommers, 2011), African Americans are far from convinced. In a Pew survey in 2007, 67% of African Americans reported that they often encountered prejudice when applying for jobs, and 50% reported that they had experienced racism when simply shopping or dining out. In a 2013 Pew survey, 88% of African Americans said that their group still experiences “some” or a “a lot” of discrimination, compared with only 57% of European Americans who believe that African Americans still experience discrimination.

Of course there is no question that great progress has been made in improving attitudes toward and treatment of ethnic minorities; women; and gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgendered individuals in the United States. Dial back time about 60 years to 1954. The U.S. Supreme Court has just announced the historic decision Brown v. Board of Education, which struck down state laws enforcing racial segregation in the public schools. The Court ruled that “separate but equal” schools for Black and White students were inherently unequal. The ruling was met with stark and at times violent opposition in a number of states. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had to call in the National Guard to protect African American children heading into and out of school in Arkansas.

Contrast that situation with where America is now. About 60 years later, we have anti-

359

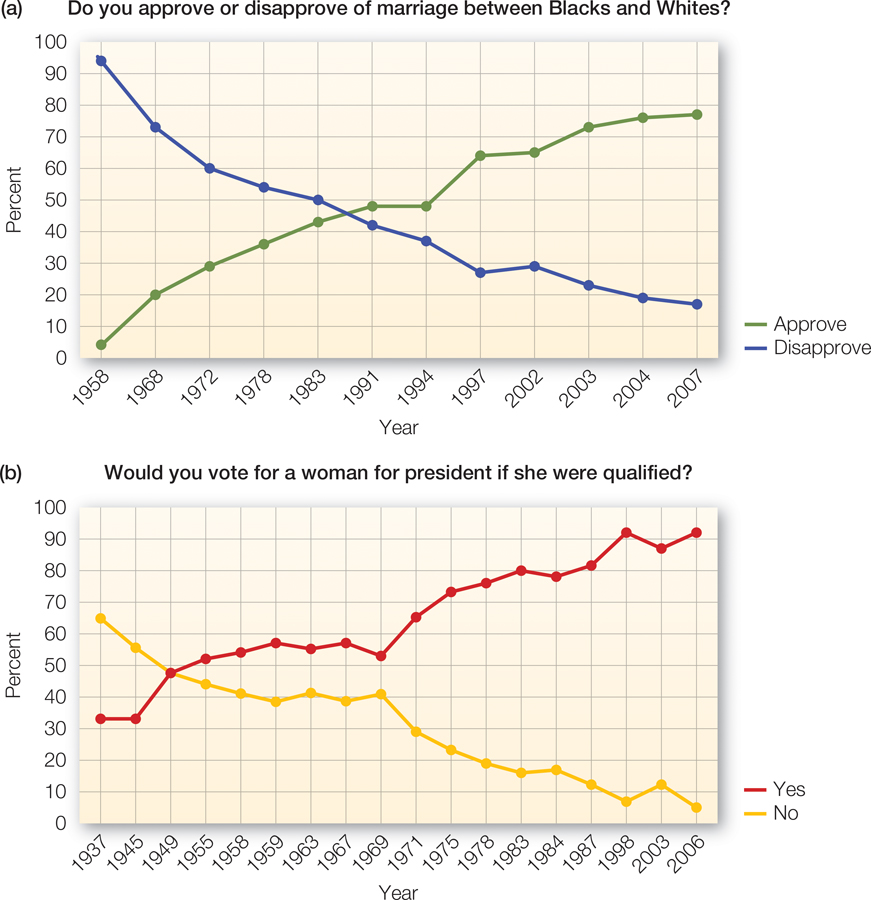

FIGURE 10.3

Changes in Prejudice Over Time

Over the last half century, Americans have reported less prejudice against minorities and women.

[Data sources: (a) Carroll, J. (2007); (b) CBS News/New York Times (2006)]

Similar changes can also be seen with other prejudices—

Think ABOUT

First, yes, segregation is against the law. But how desegregated are we really as a society? Think back to high school. Did Black students sit mainly in one part of the cafeteria, Whites in another, Hispanics in another, and Asians in yet another? Did you even attend a school or live in an area that was ethnically diverse? If people are still clustering by race and ethnicity, we might wonder whether biases still exist that shape our preferences in whom to approach and whom to avoid.

Are these social, political, and legislative strides in step with the prejudices that people express? To a large extent, at least when considering more overt expressions of prejudice, the answer is yes. FIGURE 10.3 shows the results of two polls. Looking at FIGURE 10.3a, you will see that in 1958, 94% of Americans surveyed opposed interracial marriage, a number that had dropped to 17% by 2007 (Carroll, 2007). Similarly, with regard to gender attitudes, you see in FIGURE 10.3b that in 1937, two thirds of Americans said they would not vote for a female presidential candidate, but by 2006, only 5% of Americans expressed such an absolute aversion to having a woman in the Oval Office (CBS/NY Times, 2006; Eagly, 2007). But before we conclude that problems with prejudice are all but solved, we must keep a few important points in mind.

360

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

Do Americans Live in a Postracial World?

Do Americans Live in a Postracial World?

History was made in 2008, when the United States elected its first African American president. Less than 50 years after Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke of his dream that his children would be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character, this dream seemed much closer to reality. With a multiracial president in the White House, many Americans began to wonder, Do we now finally live in a postracial world?

Probably not. Granted, the research we’ve reviewed in this chapter demonstrates that racial prejudice has changed considerably over time. The election of Barack Obama certainly signaled more positive attitudes toward African Americans likely to go beyond a desire to avoid seeming racist. However, we’ve also learned in this chapter that in the contemporary world, prejudice is filled with ambivalence and manifests itself in subtle ways. Elections often might be a time when people try to set biases aside to weigh the more established merits of different candidates. However, among undecided voters, implicit biases seem to play a stronger role in predicting decisions at the polls (Galdi et al., 2008; see also Greenwald, Smith et al., 2009). Such findings suggest that negative biases still lie below the surface of people’s consciously held values, beliefs, and intentions.

On the other hand, the mere fact that the U.S. has had a Black president means that every American citizen now has a highly visible exemplar of a successful Black political leader. Barack Obama might in this way be able to tilt Americans’ implicit associations of Blacks in a more positive direction. Indeed, there is some evidence that the election of Obama and exposure to his campaigns have helped to reduce people’s implicit race bias, in part by providing a positive example of an African American that may counter many of the negative stereotypes that are so pervasive in mass media (Plant et al., 2009; Columb & Plant, 2011). When President Obama is the example that people bring to mind when they think of Black people, they are less likely to be racially prejudiced.

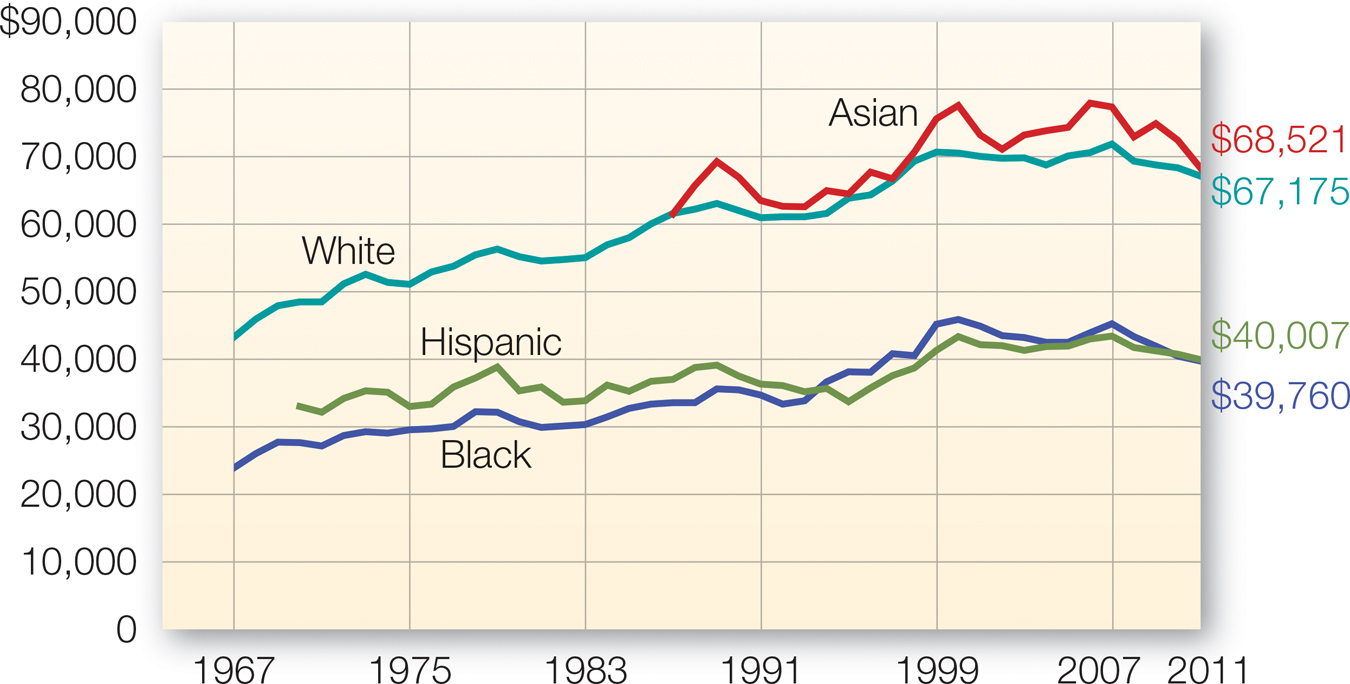

Income Disparities Since the 1960s, Hispanic and Black Americans have not progressed in terms of income compared with White Americans. In contrast, Asian Americans have done quite well.

[Data source: Pew Research (2013)]

However, we must be careful not to look at data like these and feel that we need do no more to rectify racial inequality. There are signs that the election of Obama has in fact fostered that belief—

Endorsing Obama’s election also may give Whites who are high in prejudice the moral credentials, so to speak, to think that enough has been done to improve racial equality and show stronger favoritism to Whites (Effron et al., 2009). For example, in one study participants who varied in their level of racial prejudice indicated whether they would vote for Obama or McCain in the 2008 election, or to indicate whether they would have voted for Bush or Kerry in 2004. (This condition was included to control for priming political orientation.) (Effron et al., 2009). Subsequently, participants imagined they were on a community committee with a budget surplus that could be allocated to two community organizations, one that primarily served a White neighborhood and one that primarily served a Black neighborhood.

When participants indicated they would vote for Obama, especially those higher in prejudice turned around and allocated significantly less money to the organization that would serve the Black neighborhood and more money to the organization that would serve the White neighborhood. For people with strong racial biases, acknowledging and endorsing the success of a single outgroup member seems to come at a cost to broader policies that could benefit more people. The visible success of one person does not imply the success of the group as a whole. Clearly, more work needs to be done to fully realize Dr. King’s dream.

Second, even if attitudes toward some groups have become more favorable over time, social and political contexts can bring about new hostilities that are simply targeted against different groups. Many Americans probably had few strong attitudes about Muslims or people from Arab nations before 2001. But the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon fueled anti-

361

Witness to Discrimination Video on LaunchPad

Third, although overt expressions of discrimination and racial injustice are certainly declining, they are far from absent. In the fall of 2014, protests cropped up throughout the U.S. in response to police killings of African Americans that many people viewed as outrageous and unwarranted (Huffington Post, 2014). The most publicized of these cases were: the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; the shooting of 12-

American President Barack Obama signing the Matthew Shepard Act into law on October 28, 2009.

362

But in addition to subtle and indirect forms of prejudice, extreme acts of cruelty are still evident as well. Consider the highly publicized case in 1998 in which a gay University of Wyoming student, Matthew Shepard, was beaten, tortured, and left to die (Loffreda, 2000). This horrendous crime stimulated further blatant anti-

Beyond these extreme acts, there is still ample evidence of discrimination, even though the majority of Americans believe otherwise. During the late 1950s, the civil rights campaign brought into public awareness the problem of institutional discrimination, unfair restrictions on the opportunities of certain groups of people by institutional policies, structural power relations, and formal laws (for example, a height requirement for employment as a police officer excludes most women). The more closely Americans looked at their systems of health care, criminal justice, education, and the media, the more they discovered how these systems are arranged in ways that systematically disadvantage certain groups over others. In fact, this form of discrimination is so deeply embedded in the fabric of American society that it can take place without people intending to discriminate or even their awareness that institutional practices have discriminatory effects (Pettigrew, 1958).

Institutional discrimination

Unfair restrictions on opportunities for certain groups of people through institutional policies, structural power relations, and formal laws.

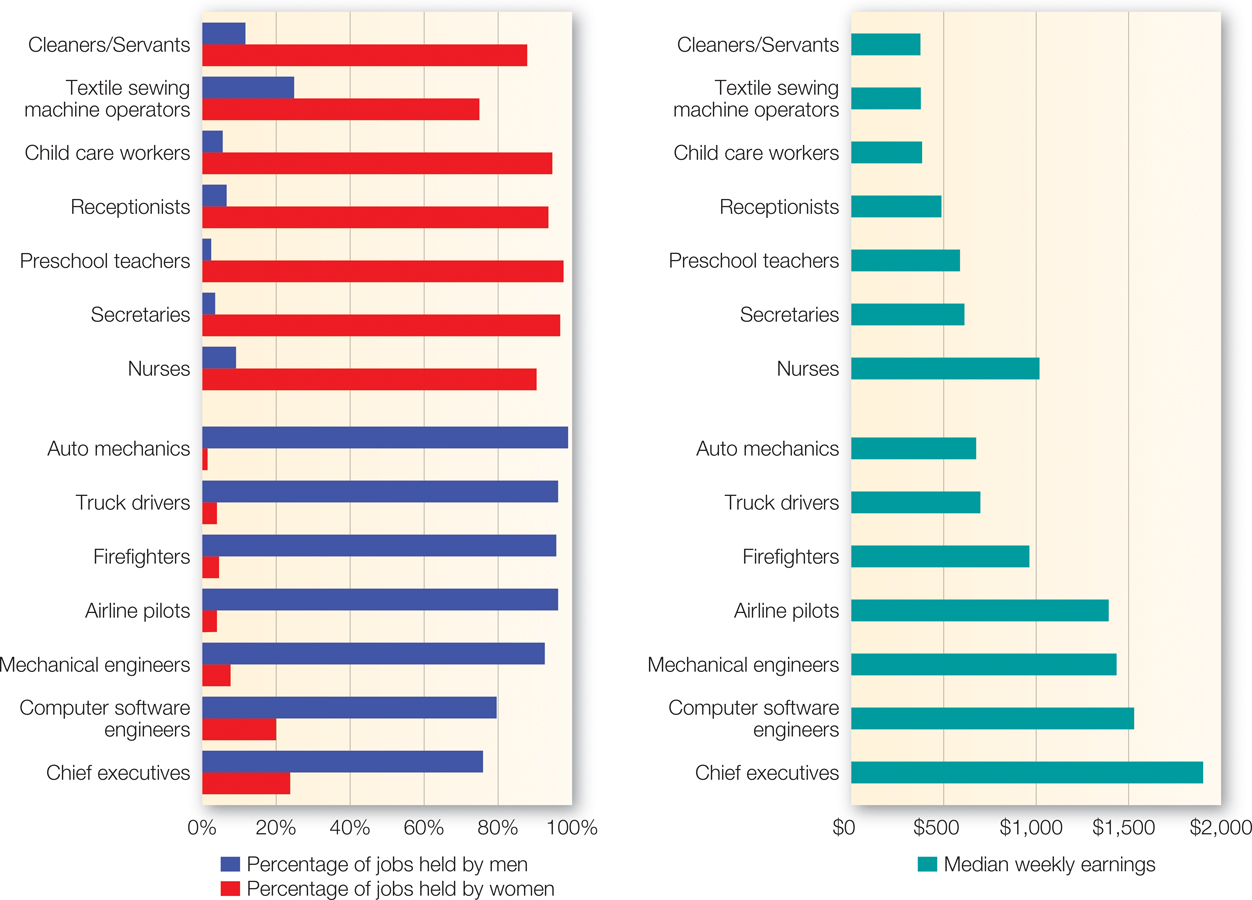

FIGURE 10.4

Women Are Underrepresented in Higher-

Women are underrepresented in some of the highest-

[Data source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009. Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2008. Report 1017. See http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpswom2008.pdf.]

Despite the heightened awareness of institutional discrimination, many examples continue today. Particularly in higher-

Clear signs of racial discrimination remain visible, whether in employment, housing, credit markets, or consumer pricing (Pager & Shepherd, 2008). For example, studies have found that pricing among fast-

363

Disparities that implicate prejudice run even deeper. Analyses of inmate records show that, for comparable crimes, Black males who have “Afrocentric” facial features—

Despite the many encouraging declines in overt prejudice in the last few decades in the United States, these findings indicate that prejudice is still very much a problem in contemporary society. But because of progress in laws and cultural norms combatting overt prejudice and discrimination, the problem has also taken on a somewhat different character. Less prevalent are the explicit signs of prejudice, such as Jim Crow laws, formerly used to mandate various forms of racial segregation, or policies that overtly prevent women from pursuing certain careers. In the contemporary world, we often see more subtle—

364

Theories of Modern Prejudice

In the early 1970s, a new understanding of prejudice emerged in social psychology. Overt demonstrations of prejudice in the United States were dissipating, yet it was clear that many people were still harboring prejudiced attitudes. Two related concepts that psychologists proposed to explain contemporary prejudice were ambivalent racism and aversive racism. Although there are some differences between these perspectives, they have much in common. Each in its own way emphasizes the need to understand how and why people might explicitly reject prejudiced attitudes but still harbor subtle biases. Let’s briefly consider each of these perspectives and what they have taught us.

Ambivalent Racism

Because of changing social norms and values associated with the civil rights movement, contemporary prejudice against African Americans in the United States is often mixed with ambivalence (Katz & Hass, 1988). The term ambivalent racism refers to racial attitudes that are influenced by two clashing sets of values: a belief in individualism, that each person should be able to make it on his or her own; and a belief in egalitarianism, that all people should be given equal opportunities. The core idea of ambivalent racism is that many Whites simultaneously hold anti-

Ambivalent racism

The influence on White Americans’ racial attitudes by two clashing sets of values: a belief in individualism and a belief in egalitarianism.

Consider Steve, who is White. He likes to think of himself as an accepting person and readily admits that Blacks have been disadvantaged in various ways. He supports affirmative action and votes in favor of using tax dollars for aid to the poor to help level the playing field. But while believing this, Steve also thinks that Blacks generally don’t try hard enough. Social psychologists would characterize Steve as having racial ambivalence. What happens with this ambivalence?

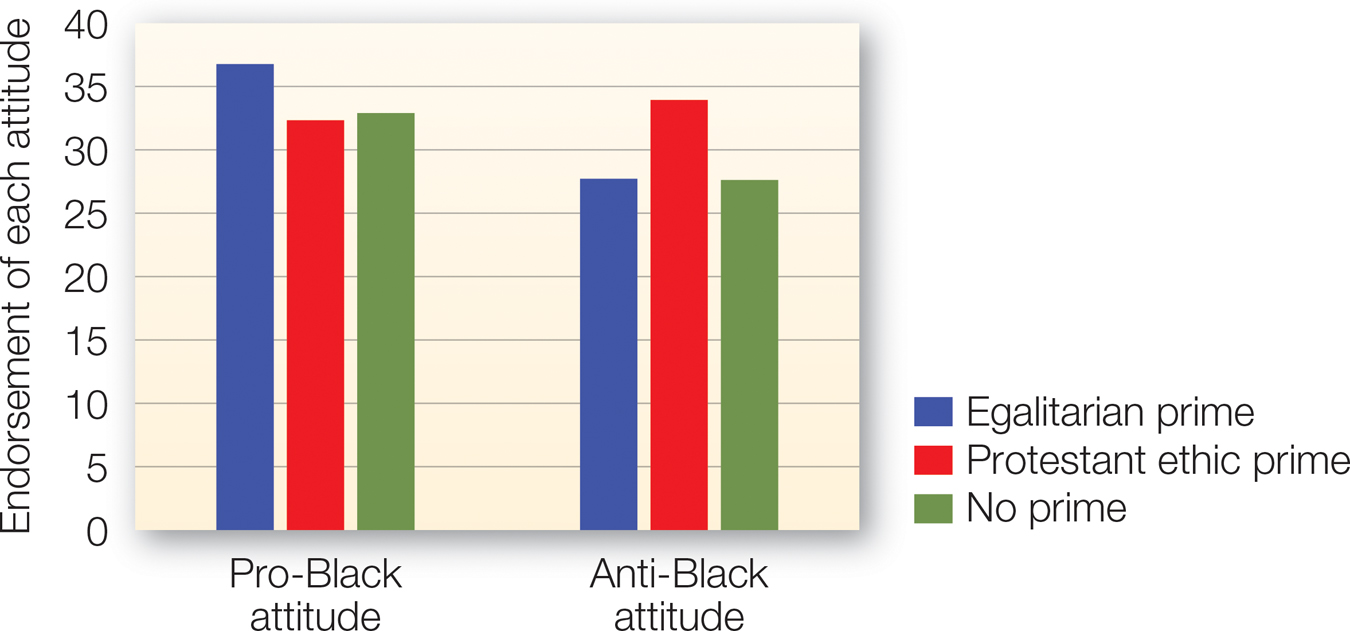

FIGURE 10.5

How Priming of Values Affects White American Attitudes Toward Black Americans

When primed to reflect on their egalitarian values, White Americans report more positive attitudes toward Blacks, but when primed with the Protestant work ethic, their attitudes become more negative.

[Data source: Katz & Hass (1988)]

Believing that each person should be able to make it on his or her own conflicts with trying to justify giving certain people (e.g., Blacks, women) special affirmative action opportunities. Depending on which set of values is primed, ambivalent people are likely to respond more strongly in one direction or the other. This response affirms one of the two sets of values, which at least temporarily reduces the ambivalence.

So how do you know which value people will affirm? Well, it depends on which value is currently most salient, or active (Katz & Hass, 1988). If people are thinking about values related to individualism, they tend to be more prejudiced, but if thinking about values related to egalitarianism, they tend to be less prejudiced. For example, let’s take a look at FIGURE 10.5. When White participants were led to think about the Protestant ethic (a belief that emphasizes the individualistic value of hard work), they were more likely to report stronger anti-

Aversive Racism

A paradox of American society—

365

Aversive racism

Conflicting, often nonconscious, negative feelings about African Americans that Americans may have, even though most do in fact support principles of racial equality and do not knowingly discriminate.

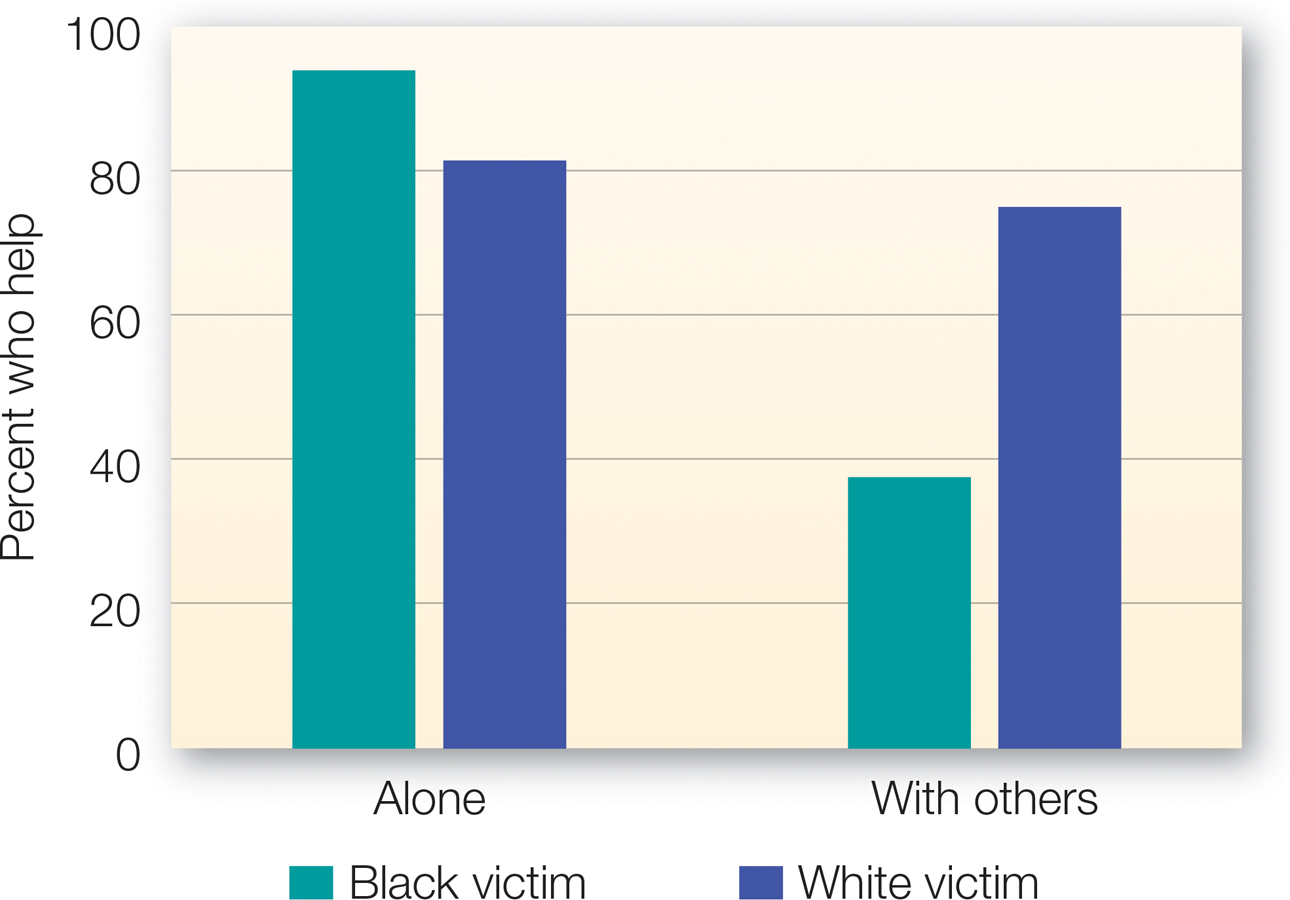

FIGURE 10.6

Evidence for Aversive Racism

When it was clear that they were the only ones who could help, White Americans were equally likely to help a Black or a White victim. But when they believed that others also heard the victim’s cry for help, White Americans were less likely to help if the victim was Black.

[Data source: Gaertner & Dovidio (1977)]

Consider some of the earliest work on aversive racism, inspired by observations and news reports that Whites were less likely to help Black motorists in need. Gaertner and Dovidio (1977) presented White participants with what the participants thought was a situation where a Black or a White person needed help. However, the researchers varied whether a White participant thought she or he was the only person to hear the plea, or whether she or he thought others were available to help. The results of the study—

Similar results are observed in employment scenarios and college application processes. For instance, discrimination is less likely to occur when applicants have especially strong or weak records (because the applicants’ records do the talking) but is more likely to occur when applicants have mixed records. That is, discrimination occurs when a gray area allows race to play a role, but it can be justified through nonracial means (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000). For example, when a Black applicant had higher SAT scores but lower high school grades than a White applicant, high-

So prejudice is more likely to occur in situations when it can be justified by some other motive. But you might be wondering, Do all people do this? Or are particular individuals most likely to act this way? To answer this question, a number of theories about prejudice suggest that it is critical to consider not just the attitudes that people are consciously willing or able to report but also those that might reside beneath their conscious awareness. Since the 1990s, there has been an explosion of interest in this concept of implicit prejudice.

Implicit Prejudice

The term implicit prejudice refers to negative attitudes toward a group of people for which the individual has little or no conscious awareness. Some people may choose not to admit their prejudices, whereas others may not be aware of them. But as we noted in our discussion of implicit attitudes in chapter 3, measures of implicit prejudice tap into attitudes that lie beneath the surface of what people report (Nosek et al., 2011). And indeed, whereas a majority of White Americans don’t report being prejudiced on explicit measures, most do show signs of having biases when their attitudes are assessed implicitly with either cognitive measures of implicit associations or physiological measures of affective responding (Dovidio et al., 2001; Cunningham et al., 2004; Hofmann et al., 2005; Mendes et al., 2002).

Implicit prejudice

Negative attitudes or affective reactions associated with an outgroup, for which the individual has little or no conscious awareness and which can be automatically activated in intergroup encounters.

366

Physiological Measures of Bias

Measures of implicit prejudice tap into people’s automatic affective response to a person or a group. Some measures do this by indexing an immediate physiological reaction that people are unlikely or find difficult to control. For example, when Whites are asked to imagine working on a project with a Black or a White partner, they often report a stronger preference for working with the Black partner. But their faces tell a different story. Electrodes connected to their brows and cheeks pick up subtle movements of the facial muscles that reveal a negative attitude when they think about working with a Black partner (Vanman et al., 2004). Similarly, when Whites are actually paired up to work with a Black partner, they show a cardiovascular response that is associated with threat—

The brain also registers the threat response. The amygdala is the brain region that signals negative emotional responses, especially fear, to things in our environment. Whites who have a strong racial bias exhibit an especially pronounced amygdala response when they view pictures of Black men (Phelps et al., 2000). Interestingly, however, if given more time, this initial negative attitude tends to get downregulated by the more rational dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Cunningham, Johnson et al., 2004; Forbes et al., 2012). This suggests that even people who acknowledge their prejudice may feel some pressure to control it. We’ll discuss why and how people go about controlling their prejudiced attitudes and emotions more in our next chapter. For now, the primary point is that automatic negative bias leaks out in people’s physiological responses.

Cognitive Measures of Implicit Bias

Although physiological measures provide insight into attitudes and affect, cognitive measures also tell us something about people’s implicit attitudes. These measures take different forms, but they all rely on the same assumption. If you like a group, then you will quickly associate that group with good stuff. If you don’t like a group, you will quickly associate that group with bad stuff. With this assumption tucked in our pocket, we can present people with members of different groups and measure how fast it takes them to identify good and bad stuff (Fazio et al., 1995; Dovidio et al., 2002).

For example, in developing one of the first studies of implicit bias, Fazio and colleagues (1995) reasoned that if Whites experience an automatic negative reaction to Blacks, then exposure to photographs of African Americans should speed up evaluations of negative words and slow down evaluations of positive words. To test this hypothesis, they presented participants with positive words (e.g., wonderful) and negative words (e.g., annoying), then asked them to indicate as fast as they could whether each was good or bad by pressing the appropriate button. Each word was immediately preceded by a brief presentation of a photograph of a Black or a White person. The results revealed substantial individual differences in White participants’ automatic reactions: For many White participants, being primed with Black faces significantly sped up reactions to negative words and slowed down reactions to positive words. Other White participants did not show this pattern, and some even showed the opposite. More important, the more closely these people seemed to associate “Black” with “bad,” the less friendly they were during a later 10-

Since the late 1990s, the most commonly used measure of implicit attitudes has been the implicit association test, or IAT (Greenwald et al., 1998), which we introduced to you in chapter 3. The basic logic of this test is that if you associate group A with “bad,” then it should be pretty easy to group together instances of group A and instances of bad stuff, and relatively difficult to group together instances of group A and instances of good stuff. This basic paradigm can be used to assess implicit associations with any group you can think of, but it has most commonly been used for race, so let’s take that example. You can take this and other versions of the IAT test yourself by visiting the Project Implicit web site at www.projectimplicit.com.

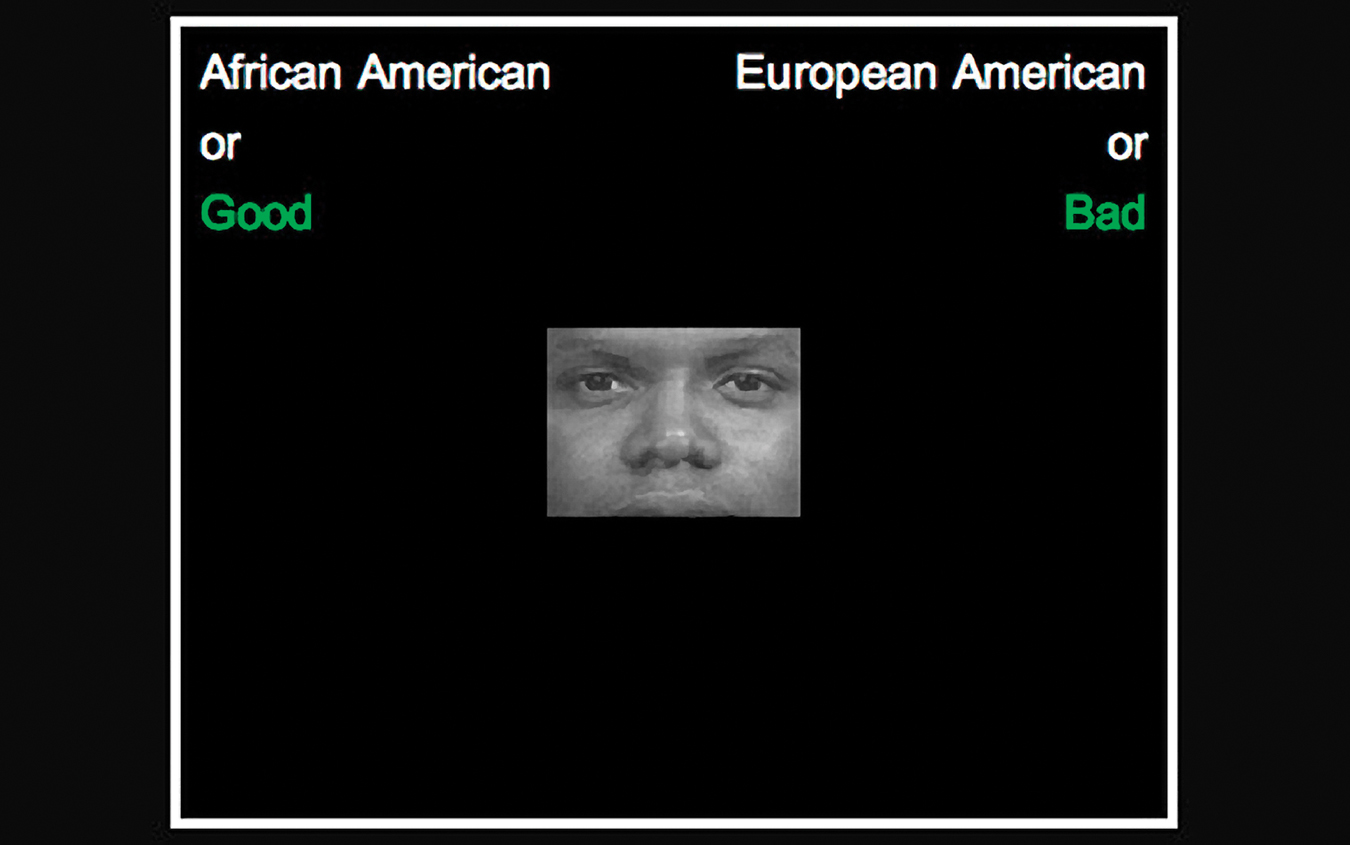

FIGURE 10.7

A Classic Measure of Implicit Racism

The Implicit Association Test measures the relative difficulty people can have in automatically associating Black faces with good thoughts.

[Data source: Greenwald et al. (1998)]

In the Race IAT, people are instructed to do some basic categorization tasks (FIGURE 10.7). The first two rounds are just practice getting used to the categories. For the first round, you are presented with White and Black faces one at a time, and you just need to click on one button if the face is Black and another button if the face is White. In the second round, you categorize positive (“rainbow,” “present”) and negative (“vomit,” “cancer”) words by clicking on one button if the word is positive and a different button if the word is negative. In the third round, the task becomes more complicated as you are presented with both faces and words, one at a time. Deciding as quickly as possible, you must then click one button if what you see is either a Black face or a positive word but a different button if you see either a White face or a negative word. When your cognitive network links “Black” with “bad,” it’s relatively hard to use the same button to categorize Black faces along with positive words without either slowing down or making lots of category errors. In contrast, if “Black” and “bad” are closely associated in your cognitive network, you should find it much easier to use the same button to indicate that you see either a Black face or negative word, the task required in a fourth round. The average difference in time it takes to make these dual category judgments (measured in milliseconds) is the measure of cognitive association.

367

Research using this kind of measure has shown that most Whites and a substantial proportion of Blacks (though usually not greater than 50%) show an implicit association of “Black” with “bad.” What is less clear is what this association means. Some researchers have criticized the measure for confounding the tendency to associate “Black” and “bad” with the tendency to associate “White” and “good” (Blanton & Jaccard, 2006; Blanton et al., 2006). However, other evidence suggests that IAT scores do reliably assess responses that are predictive of behavior (Greenwald et al., 2009; LeBel & Paunonen, 2011). Even if we grant that the IAT is a reliable measure, some dispute continues about what it taps into. For example, people actually show stronger racial biases when they know the measure is supposed to reveal their racial biases (Frantz et al., 2004). Anxiety about being labeled racist might actually make it more difficult for people to perform the task. In addition, some researchers have noted that an association of “Black” with “bad” could mean a variety of things, such as the acknowledgment that Blacks are mistreated and receive bad outcomes, or simply cultural stereotypes that might have little to do with one’s personal attitudes (Andreychik & Gill, 2012; Olson & Fazio, 2004).

Even if we set aside the debate about the IAT in particular, a broader pattern emerges from the literature examining both implicit and explicit measures of prejudiced attitudes. Most notable, although they can be correlated, they are often quite distinct. In other words, people who have an implicit negative attitude toward a group might still explicitly report having positive feelings. But even more interesting is that people’s implicit attitudes seem to predict different kinds of behavior than their explicit attitudes. Let’s consider one study that has shown this most clearly.

Dovidio and colleagues (2002) had students participate in what they thought were two unrelated studies. In the first, the researchers measured implicit prejudice using a cognitive association task like the one Fazio developed in 1995. The researchers measured explicit prejudice by having White participants complete a questionnaire asking them outright how much prejudice they felt toward African Americans. After this, the participants proceeded to what they thought was an unrelated study in which they would have a brief, videotaped interaction with a Black person (actually a confederate). After the conversation, the participants were asked to judge how friendly they were toward their partners. The confederates made their own judgments of how friendly the participants seemed. Finally, the video and the audio soundtrack of the interaction were separately coded by a different group of raters whose only job was to judge how friendly the participant seemed during the interaction.

368

The patterns of relationships among these six variables were very telling. People’s implicit “outgroup = bad” attitudes and explicit “I value being a nonprejudiced person” attitudes predicted very different things about the interaction. White students who explicitly reported being nonprejudiced were coded (only on the basis of the audio recording of what they said) as coming across in a friendly way during a discussion with a Black student, and they came away from the conversation feeling good about the interaction. But their consciously endorsed values did not predict how coders rated their nonverbal cues (on the basis of only the video without sound) or how their Black partners perceived them. Instead, Whites who had a more negative implicit association with Blacks showed more nonverbal signs of discomfort and anxiety—

|

Is Prejudice an Ugly Thing of the Past? |

|

Although overt discrimination is declining, modern, subtler forms of prejudice persist. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Theories of modern prejudice Evidence of institutional discrimination reveals how biases can be so embedded in the structure of our society that discrimination can occur without intention. |

Ambivalent and aversive racism Ambivalent racism is the coexistence of positive and negative attitudes about Blacks resulting from clashing beliefs in individualism and egalitarianism. Aversive racism occurs when people have nonconscious, negative feelings even when they consciously support racial equality. |

Implicit prejudice Implicit prejudice refers to automatically activated, negative associations with outgroups. These associations can be revealed through physiological or cognitive measures, such as the IAT. |