12-1 Identifying the Causes of Behavior

We may think that the most obvious explanation for our behavior is simply that that we act in a state of free will: we do what we want to, and we always have a choice. But free will is not a likely cause of behavior.

Consider Roger. We first met 25-

Later, as we wandered about the ward, we encountered a worker replacing linoleum floor tiles. Roger was watching the worker, and as he did, he dipped his finger into the pot of gluing compound and licked the glue from his finger, as if he were sampling honey from a jar. When we asked Roger what he was doing, he said that he was really hungry and that this stuff was not too bad. It reminded him of peanut butter.

One of us tasted the glue and concluded that it did not taste like peanut butter. It tasted awful. Roger was undeterred. We alerted a nurse, who quickly removed him from the glue. Later, we saw him eating flowers from another bouquet.

Neurological testing revealed that a tumor had invaded Roger’s hypothalamus at the base of his brain. He was indeed hungry all of the time and in all likelihood could consume more than 20,000 calories a day if allowed to do so.

Would you say that Roger was exercising free will regarding his appetite and food preferences? Probably not. Roger seemed compelled to eat whatever he could find, driven by a ravenous hunger. The nervous system, not an act of free will, produced this behavior and undoubtedly produces many others.

If free will does not adequately explain why we act as we do, what does? One obvious answer is that we do things that we find rewarding. Rewarding experiences must activate brain circuits that make us feel good. Consider the example of prey killing by domestic cats.

One frustrating thing about being a cat owner is that even well-

To provide an answer, we look to the activities of neural circuits. Cats must have a brain circuit that controls prey killing. When this circuit is active, a cat makes an “appropriate” kill. Viewed in an evolutionary context, it makes sense for cats to have such a circuit: in the days when doting humans did not keep cats as pets, cats did not have food dishes that were regularly filled.

Why does this prey-

Many people find watching and sharing cute cat videos rewarding: it makes them feel good, and they do it often.

In the wild, after all, a cat that did not like killing would probably be dead. In the early 1960s, Steve Glickman and Bernard Schiff (1967) first proposed the idea that behaviors such as prey killing are rewarding. We return to reward in Section 12-6 because it is important in understanding the causes of behavior.

Behavior for Brain Maintenance

Some experiences are rewarding; others are aversive, again because brain circuits are activated to produce behaviors that reduce the aversive experience. One example is the brain’s inherent need for stimulation.

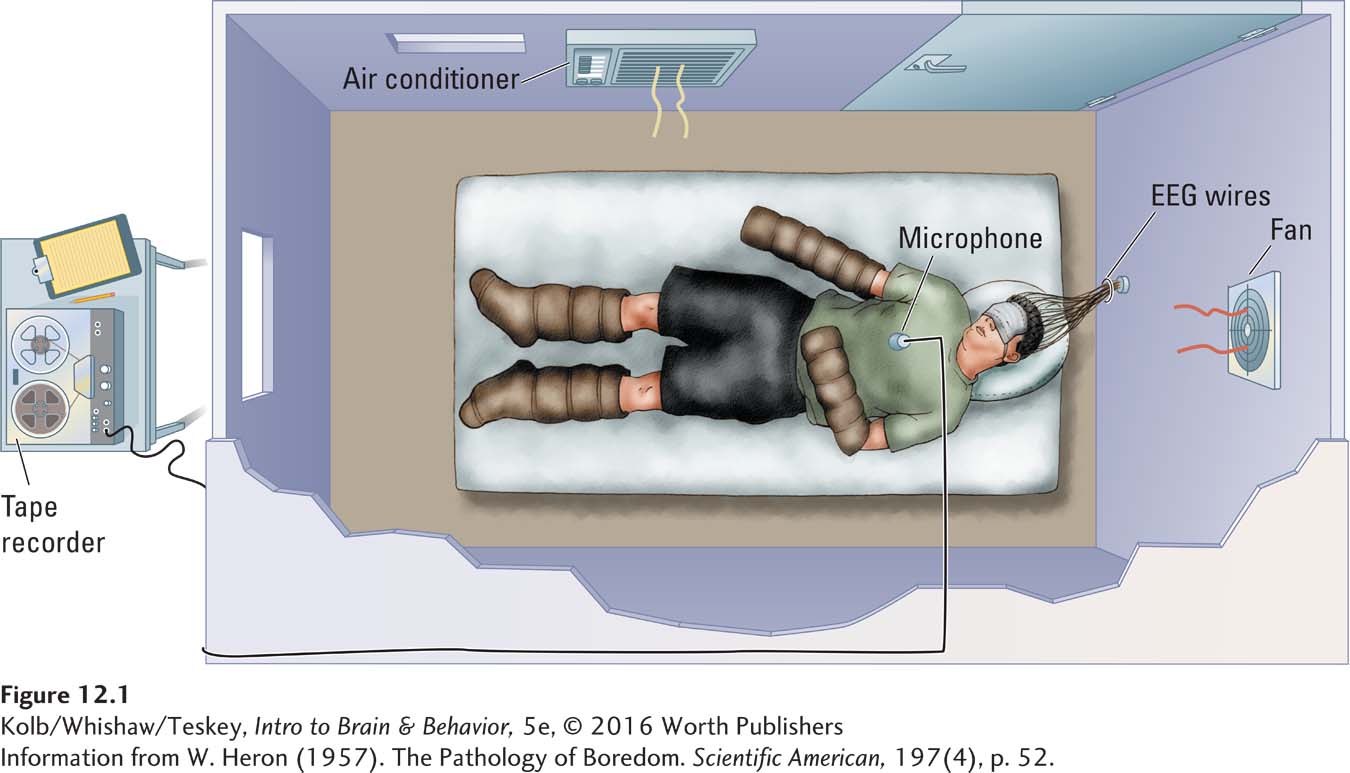

Donald Hebb and his coworkers (Heron, 1957) studied the effects of sensory deprivation, depriving people of nearly all sensory input. They wanted to see how well-

Each student lay on a bed in a small, soundproofed room with ears enveloped by a hollowed-

Wouldn’t you think the participants would be ecstatic to contribute to scientific knowledge in such a painless way? In fact, they were far from happy. Most were content for perhaps 4 to 8 hours; then they became increasingly distressed. They craved stimulation of almost any kind. In one version of the experiment, the participants could listen, on request, to a talk for 6-

What caused their distress? Why did they find sensory deprivation so aversive? The answer, Hebb and colleagues concluded, must be that the brain has an inherent need for stimulation.

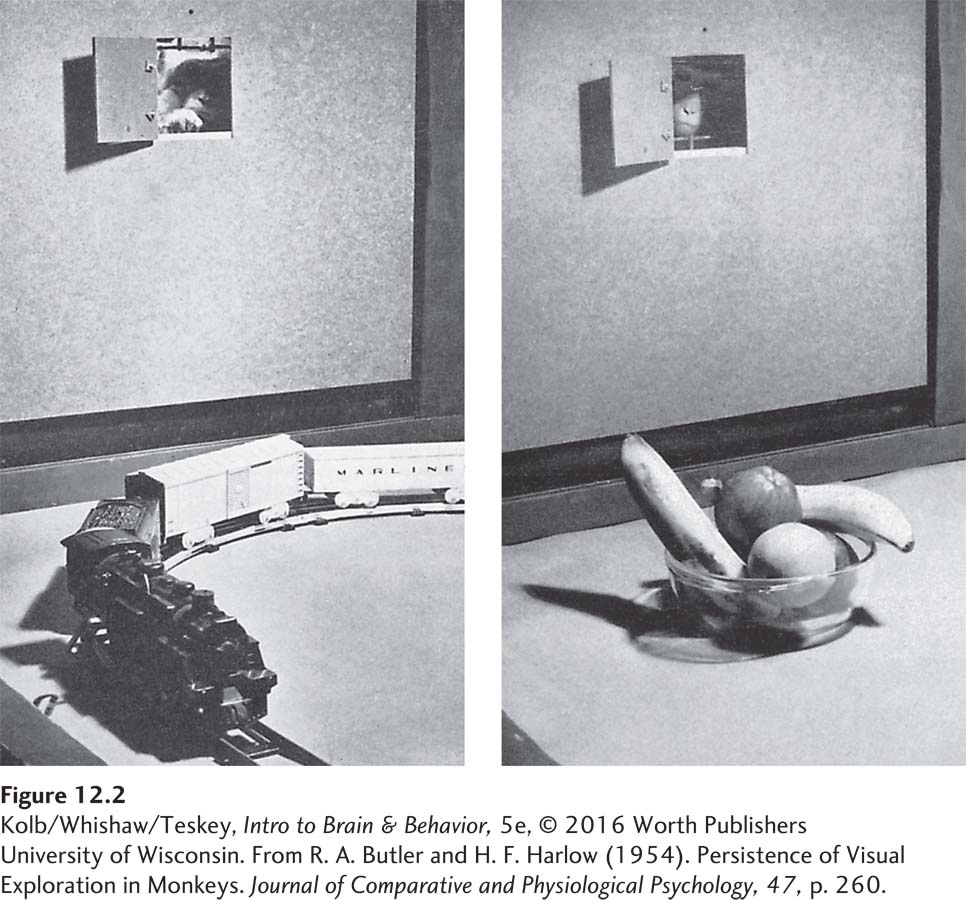

Psychologists Robert Butler and Harry Harlow (1954) came to a similar conclusion through a series of experiments they conducted at about the same time Hebb conducted his sensory deprivation studies. Butler placed rhesus monkeys in a dimly lit room with a small door that could be opened to view an adjoining room. As shown in Figure 12-2, the researchers could vary the stimuli in the adjoining room so that the monkeys could view different objects or animals each time they opened the door.

University of Wisconsin

Monkeys in these conditions spent a lot of time opening the door and viewing whatever was on display, such as toy trains circling a track. The monkeys were even willing to perform various tasks just for an opportunity to look through the door. The longer they were deprived of a chance to look, the more time they spent looking when finally given the opportunity.

The Butler and Harlow experiments, together with Hebb and colleagues’ research on sensory deprivation, show that in the absence of stimulation, the brain will seek it out.

Neural Circuits and Behavior

Researchers have identified brain circuits for “reward” and discovered that these circuits can modulate to increase or decrease activity. Researchers studying the rewarding properties of sexual activity in males, for example, found that a man’s frequency of copulation correlates with his levels of androgens (male hormones). Unusually high androgen levels are related to ultrahigh sexual interest; abnormally low androgen levels are linked to low sexual interest or perhaps no interest at all. The brain circuits are more difficult to activate in the absence of androgens.

Another way to modulate reward circuits comes via our chemical senses, smell and taste. The odor of a mouse can stimulate hunting in cats, whereas the odor of a cat will drive mice into hiding. Similarly, the smell from a bakery can make us hungry, whereas foul odors can reduce the rewarding value of our favorite foods. Although we tend to view the chemical senses as relatively minor in our daily lives, they are central to motivated and emotional behavior, as discussed next, in Section 12-2.

Understanding the neural basis for motivated behavior has wide application. For instance, we can say that Roger had a voracious and indiscriminate appetite either because the brain circuits that initiate eating were excessively active or because the circuits that terminate eating were inactive. Similarly, we can say that Hebb’s participants were highly upset by sensory deprivation because the neural circuits that respond to sensory inputs were forced into abnormal underactivity. So the main reason for a particular thought, feeling, or action lies in what is going on in brain circuits.

12-1 REVIEW

Identifying the Causes of Behavior

Before you continue, check your understanding.

Question 1

One reason cats kill when they may not be hungry is that the killing behavior is ________________.

Question 2

A reason animals get bored and seek new things to do is to maintain a(n)___________________.

Question 3

Which senses strongly modulate neural circuits?

Question 4

Why is free will inadequate to explain why we do the things we do?

Answers appear in the Self Test section of the book.