13-1 A Clock for All Seasons

We first consider evidence that proved the existence of a biological clock: how the clock keeps time and how it regulates our behavior. Because environmental cues are not always consistent, we examine how biological clocks help us interpret environmental cues in an adaptive way.

Origins of Biological Rhythms

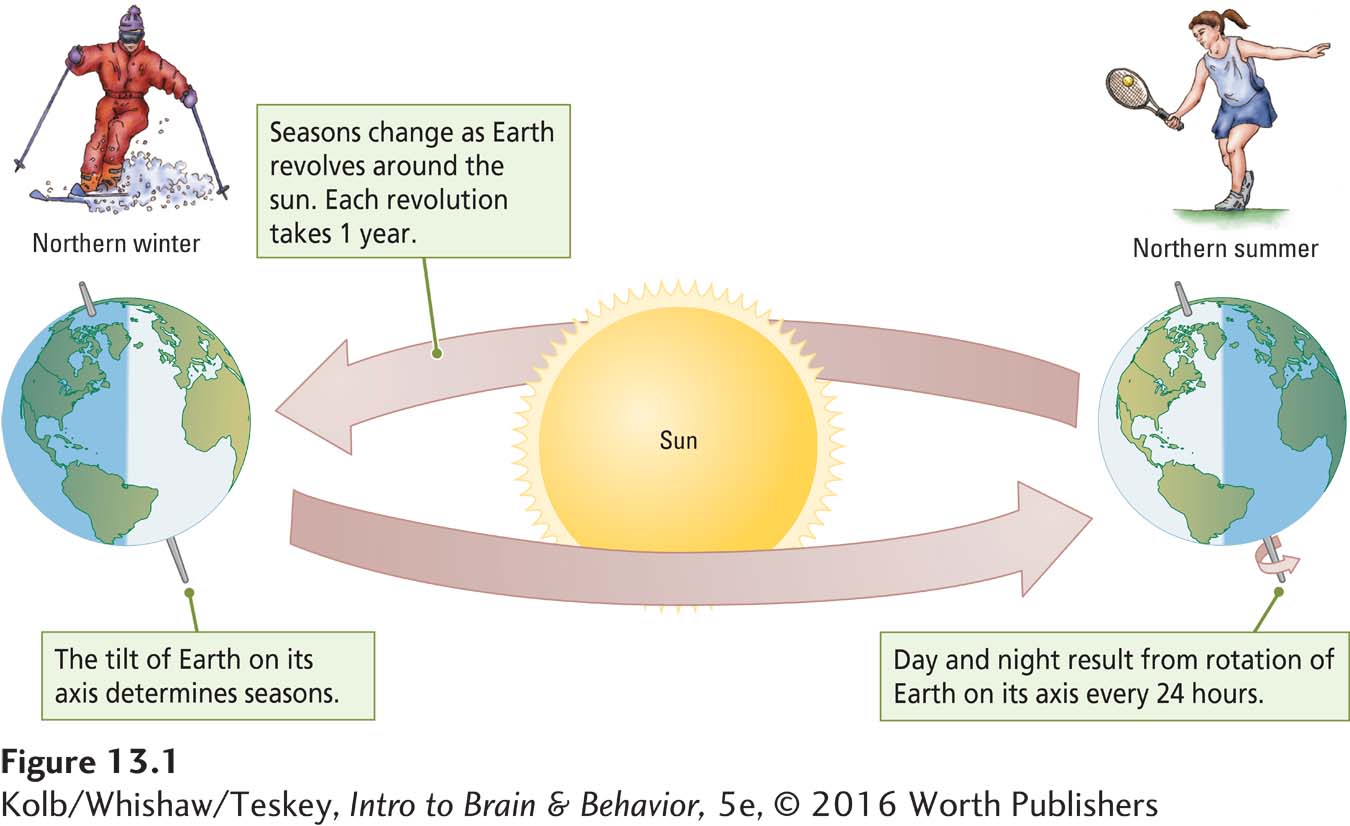

Biorhythms, the inherent timing mechanisms that control or initiate various biological processes, are linked to the cycles of days and seasons produced by Earth’s rotation on its axis and by its progression in orbit around the sun (Figure 13-1). Earth rotates on its axis once every 24 hours, producing a 24-

Earth’s axis is tilted slightly, so as it orbits the sun once each year, the North and South Poles incline slightly toward the sun for part of the year and slightly away from it for the rest of the year. As the Southern Hemisphere inclines toward the sun, its inhabitants experience summer: more direct sunshine for more hours each day, and the weather is warmer. At the same time inhabitants of the Northern Hemisphere, inclined away from the sun, experience winter: less direct sunlight, making the days shorter and the weather colder. Over the year the polar inclinations reverse, as do the seasons. Tropical regions near the equator undergo little seasonal or day length change as Earth progresses around the sun.

Daily and seasonal changes have combined effects on organisms, inasmuch as the onset and duration of daily change depend on the season and latitude. Animals living in polar regions have to cope with greater seasonal fluctuations in daily temperature, light, and food availability than do animals living near the equator.

We humans largely evolved as equatorial animals, and our behavior is dominated by a circadian rhythm of daylight activity and nocturnal sleep. Nevertheless our daily cycles adapt to extreme latitudes. Not only does human waking and sleep behavior cycle daily; so also do pulse rate, blood pressure, body temperature, rate of cell division, blood cell count, alertness, urine composition, metabolic rate, sexual drive, feeding behavior, and responsiveness to medications. The activity of nearly every cell in our bodies shares a daily rhythm.

Biorhythms are not unique to animals. Plants display rhythmic behavior exemplified by species whose leaves or flowers open during the day and close at night. Even unicellular algae and fungi display rhythmic behaviors related to the passage of the day. Some animals, including lizards and crabs, change color in a rhythmic pattern. The Florida chameleon, for example, turns green at night, whereas its coloration matches its environment during the day. In short, almost every living organism and every living cell displays rhythms related to daily changes (Bosler et al., 2015).

Biological Clocks

If animal behavior were affected only by daily changes in external cues, the neural mechanisms that account for changes in behavior would be simple to study. An external cue—

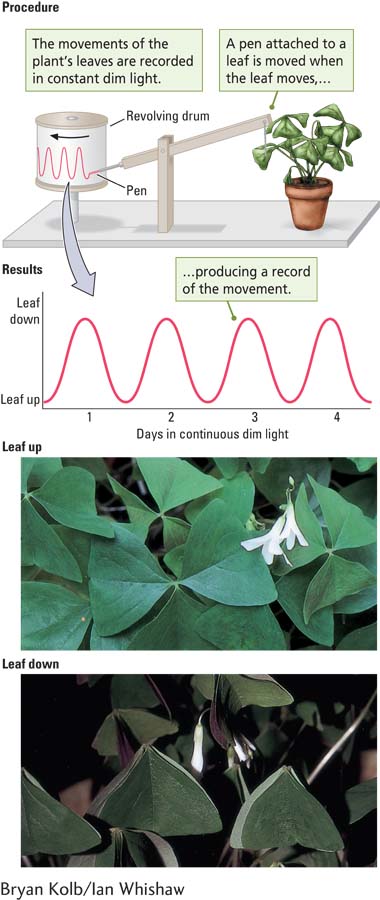

That behavior is not driven simply by external cues was first recognized in 1729 by the French geologist Jean Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan (see Raven et al., 1992). In an experiment similar to the one illustrated in the Procedure section of Experiment 13-1, de Mairan isolated a plant from daily light, dark, and temperature cues. He noted that the rhythmic movements of its leaves seen over a light–

EXPERIMENT

Question: Is plant movement exogenous or endogenous?

Conclusion: Movement of the plant is endogenous. It is caused by an internal clock that matches the temporal passage of a real day.

What concerned investigators who came after de Mairan was the possibility that some undetected external cue stimulates the plant’s rhythmic behavior. Such cues could include changes in temperature, in electromagnetic fields, and even in the intensity of cosmic rays from outer space. But further experiments showed that daily fluctuations are endogenous—

Similar experiments show that almost all organisms, including humans, have biological clocks that synchronize behavior to the temporal passage of a real day and make predictions about tomorrow. A biological clock signals that if daylight lasts for a given time today, it will last for about the same time tomorrow. A biological clock allows us to anticipate events and prepare for them both physiologically and cognitively. And unless external factors get in the way, a biological clock regulates feeding times, sleeping times, and metabolic activity as appropriate to day–

Measuring Biological Rhythms

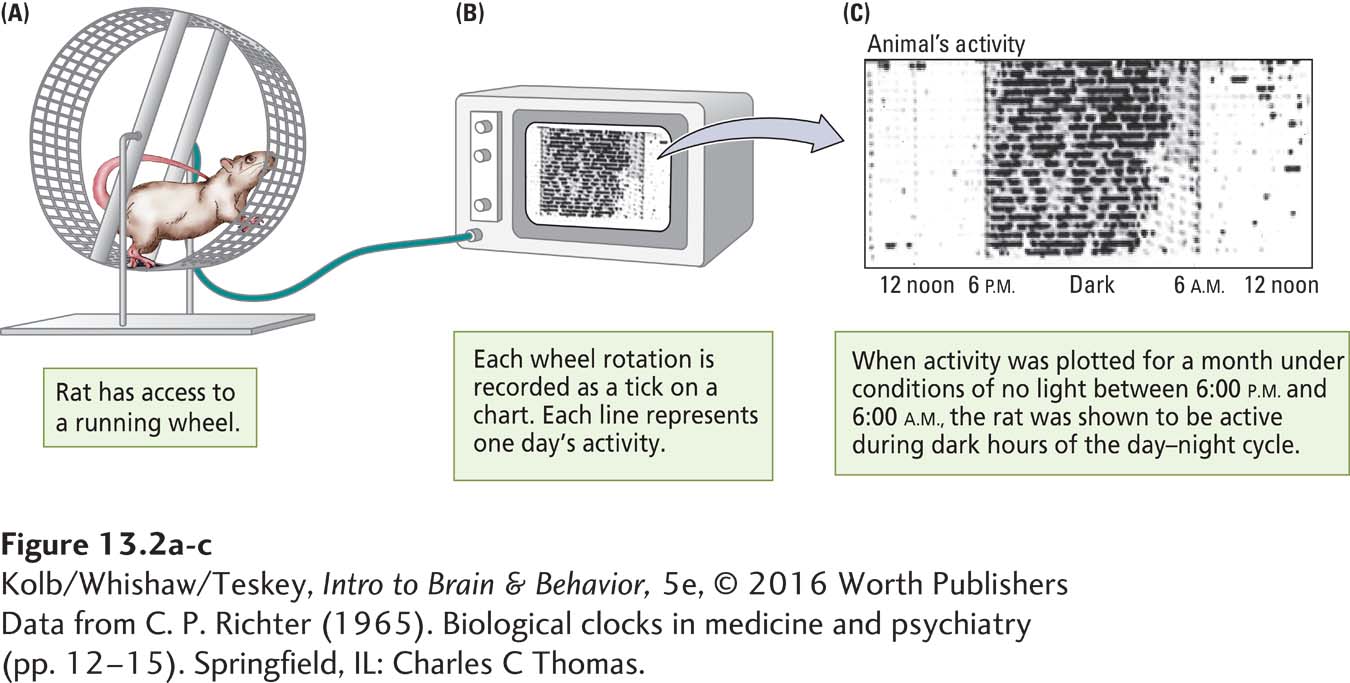

Although the existence of endogenous biological clocks was demonstrated nearly 300 years ago, detailed study of biorhythms had to await the development of electrical and computer-

A computer records each turn of the wheel and displays the result (Figure 13-2B). Because most rodents are nocturnal, sleeping during light hours and becoming active during dark hours, their wheel running takes place in the dark. If each day’s activity is plotted under the preceding day’s activity in a column, we observe a pattern—

The animal’s activity cycle has a period, the time required to complete one cycle of activity. Most animals’ activity period is about 24 hours in an environment in which the lights go on and off regularly. Our own sleep–

In Latin circa means about, annum means year, and dies means day.

Many behaviors have periods longer or shorter than this 24-

Ultradian rhythms have a period of less than one day. Our eating behavior, which takes place about every 90 minutes to 2 hours, including snacks, is one ultradian rhythm. Rodents, although active throughout the night, display an ultradian rhythm in being most active at the beginning and end of the dark period.

| Biological rhythm | Time frame | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Circannual | Yearly | Migratory cycles of birds |

| Circadian | Daily | Human sleep– |

| Infradian | More than a day | Human menstrual cycle |

| Ultradian | Less than a day | Human eating cycles |

The fact that a behavior appears to be rhythmic does not mean that it is ruled only by a biological clock. Animals may postpone migrations as long as food supplies last. They adjust their circadian activities in response to the availability of food, the presence of predators, and competition from other members of their own species. We humans obviously change our daily activities in response to seasonal changes, work schedules, and play opportunities. Therefore, whether a rhythmic behavior is produced by a biological clock and the extent to which it is controlled by a clock must be demonstrated experimentally.

Free-Running Rhythms

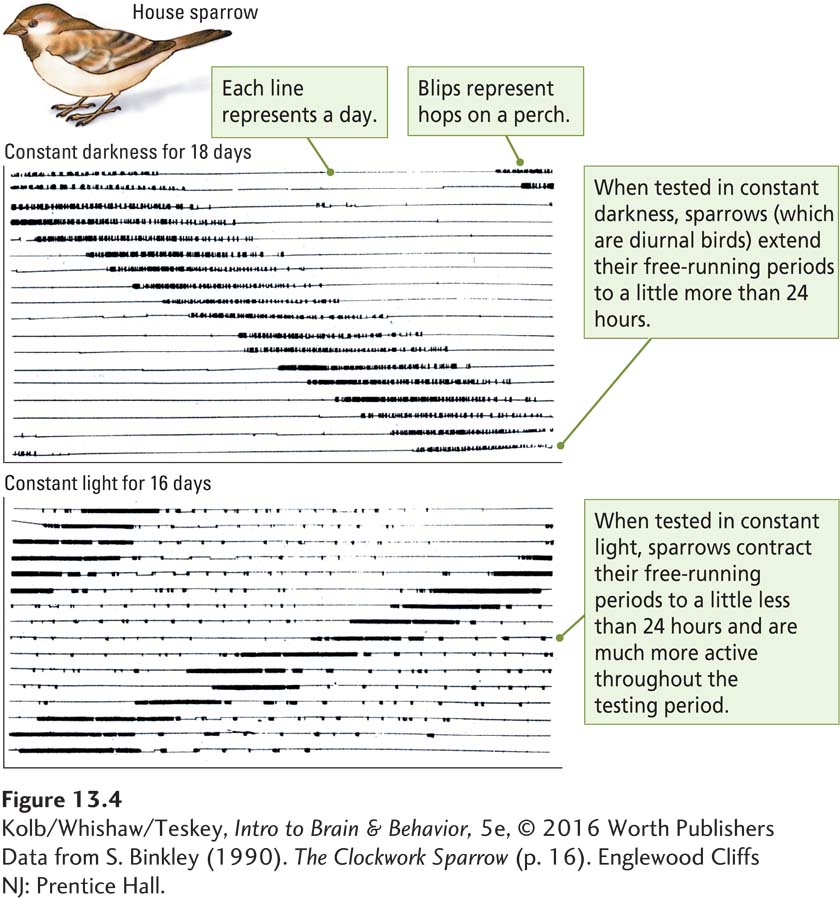

To determine whether a rhythm is produced by a biological clock, researchers design three types of tests in which they manipulate relevant cues, especially light cues. A test is given (1) in continuous light, (2) in continuous darkness, or (3) by choice of the participant. Each treatment yields a slightly different insight into the periods of biological clocks.

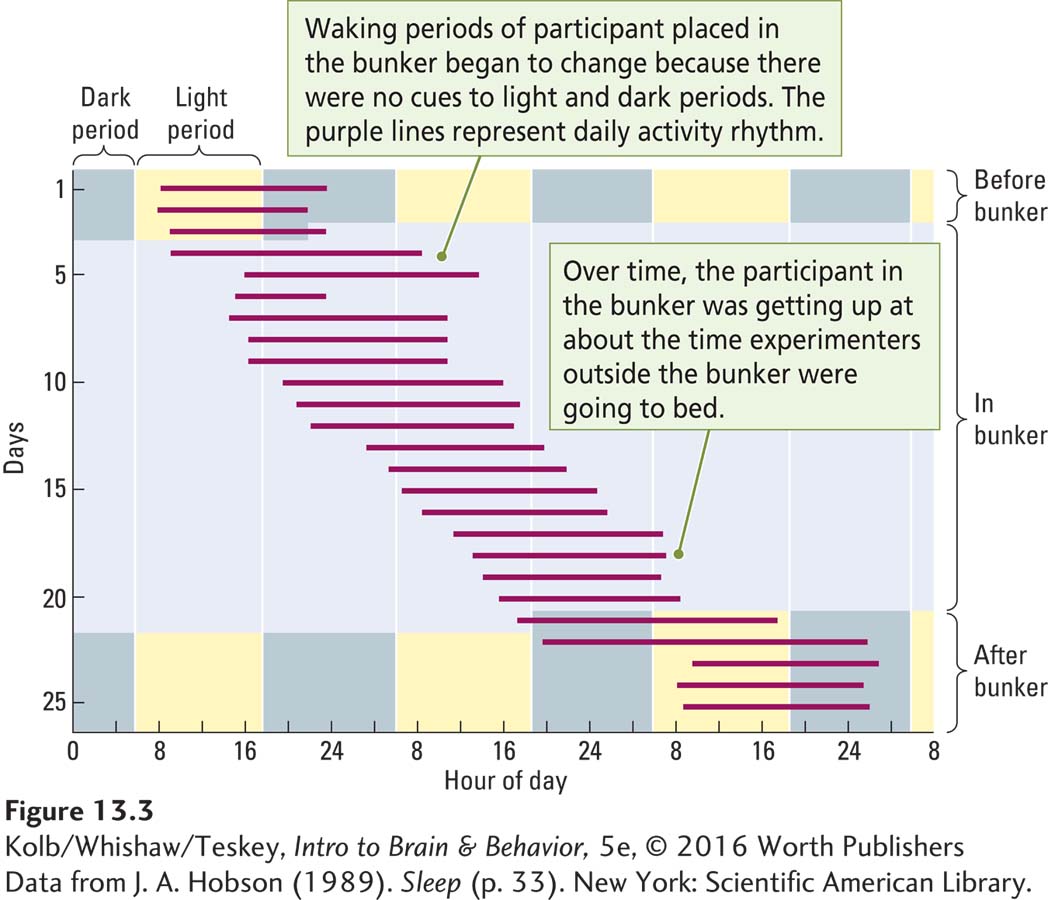

Jurgen Aschoff and Rutger Weber first demonstrated that the human sleep–

Measures of ongoing behavior and recording of sleep periods with sensors on the beds revealed that the participants continued to show daily sleep–

The participants chose to go to bed 1 to 2 hours later every “night.” Soon they were getting up at about the time the experimenters outside the bunker were going to bed. Clearly. the participants were displaying their own personal cycles. Such a free-

The period of free-

A rule of thumb to explain the period of free-

Zeitgebers

Endogenous rhythmicity is not the only factor that contributes to circadian periods. A mechanism exists for setting rhythms to correspond to environmental events as well. To be useful, the biological clock must keep to a time that predicts actual changes in the day–

If we reset an errant wristwatch each day, however—

Aschoff and Weber called a clock-

The property that allows a biological clock to be entrained explains how circadian rhythms synchronize with seasonal changes in day–

A biological clock that resets each day tells an animal that daylight will begin tomorrow at approximately the same time that it began today and that tomorrow will last approximately as long as today did. Current research finds that light Zeitgebers are effective at both sunrise and sunset: morning light sets the biological clock by advancing it, and evening darkness sets the clock by retarding it (Schmal et al., 2015).

The potent entraining effect of light Zeitgebers is illustrated by laboratory studies of Syrian hamsters, perhaps one of the most compulsive animal timekeepers. When given access to running wheels, hamsters exercise during the night segment of the laboratory day–

Considering the less compulsive behavior that most of us display, we should shudder at the way we entrain our own clocks when we stay up late in artificial light, sleep late some days, and get up early by using an alarm clock on other days. Light pollution, the extent to which we are exposed to artificial lighting, disrupts circadian rhythms and accounts for a great deal of inconsistent behavior associated with accidents, daytime fatigue, alterations in emotional states, obesity, diabetes, and other disorders characteristic of metabolic syndrome described in Clinical Focus 13-1, Doing the Right Thing at the Right Time (Gerhart-Hines & Lazar, 2015).

Entrainment works best if the adjustment made to the biological clock is not too large. People who work night shifts are often subject to huge adjustments, especially when they work the graveyard shift (11:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M.), the period when they would normally sleep. Study results show that adapting to such a change is difficult and stressful, and it increases susceptibility to disease by altering immune system rhythms (Labrecque & Cermakian, 2015). Compared with people who have a regular daytime work schedule, people who work night shifts have a higher incidence of metabolic syndrome. Thus, shift workers benefit from vigilance in maintaining good sleep habits and diet and in exercising to minimize other risk factors for metabolic syndrome. Adaptations to shift work fare better if people first work the swing shift (3:00 P.M. to 11:00 P.M.) for a time before beginning the graveyard shift.

13-2

Seasonal Affective Disorder

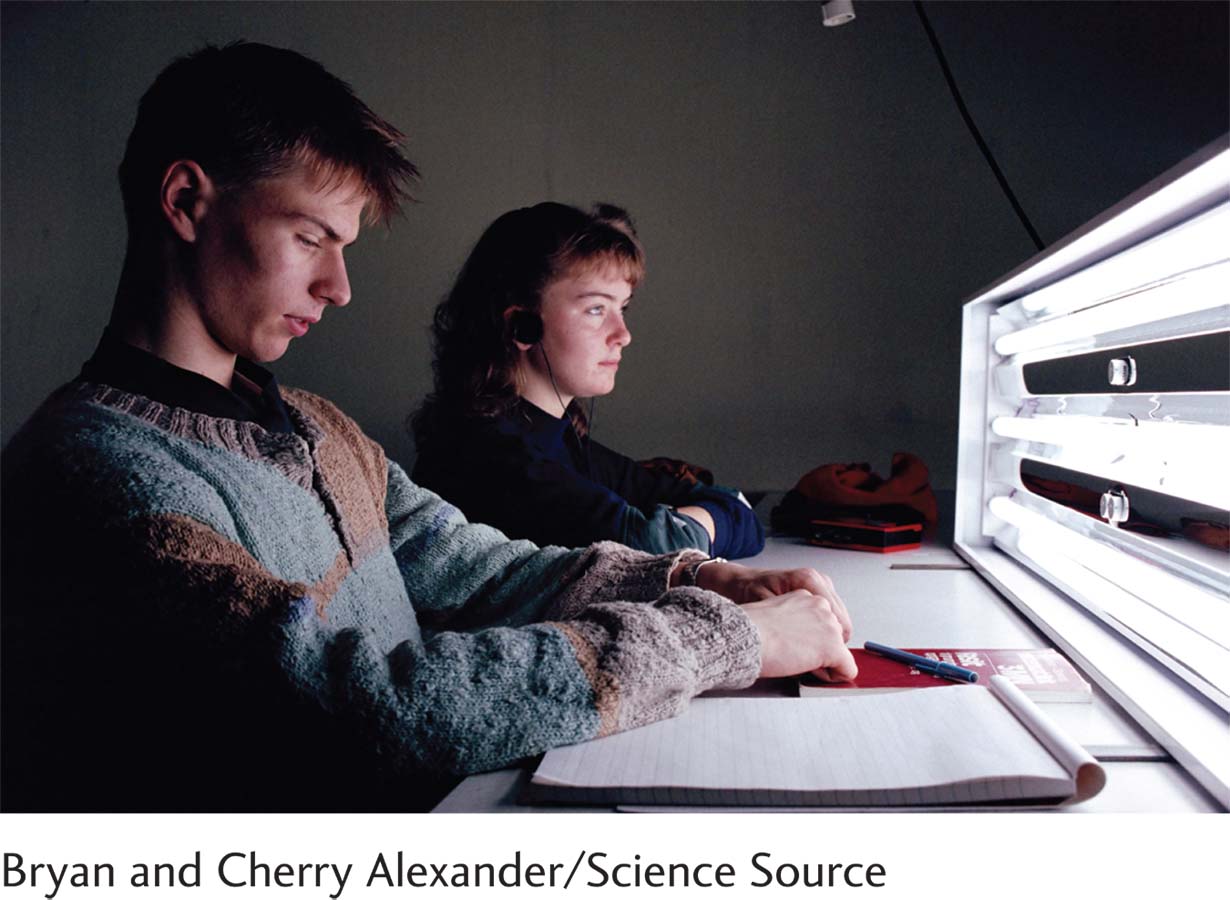

In seasonal affective disorder (SAD), a form of depression, low levels of sunlight in winter, do not entrain the circadian rhythm. Consequently, a person’s biorhythm becomes a free-

Because people vary in the duration of their free-

The cumulative changes associated with altered circadian rhythms can promote depression. The finding that incidence of depressive symptoms increases as a function of the latitude at which a person lives supports this idea.

Because a class of retinal ganglion cells that express a photosensitive pigment called melanopsin are responsive to blue light (see Section 13-2), it has been proposed that exposure to bright white light that contains this blue frequency can reset the circadian clock and ameliorate depression. In this treatment, called phototherapy, the idea is to increase the short winter photoperiod by exposing a person to artificial bright light in the morning or both morning and evening (Mårtensson et al., 2015). Typical room lighting is not bright enough.

A word of caution, however. Decreased exposure to sunlight in winter can result in Vitamin D deficiency and is also suggested to contribute to depression (Kerr et al., 2015).

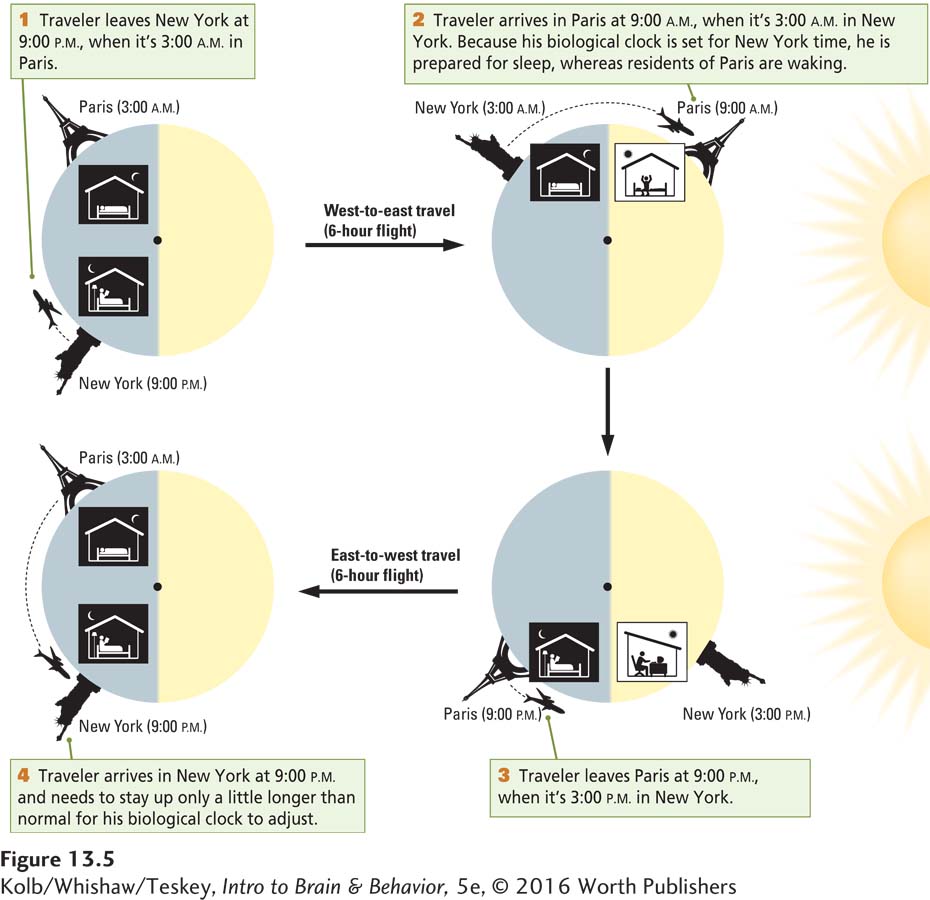

Long-

The west-

13-1 REVIEW

A Clock for All Seasons

Before you continue, check your understanding.

Question 1

Many behaviors occur in a rhythmic pattern in relation to time. These biorhythms may display a yearly, or ____________, cycle or a daily, or ____________, cycle.

Question 2

Although biological clocks keep fairly good time, their ____________ rhythms may be slightly shorter or longer than 24 hours unless they are reset each day by ____________.

Question 3

____________ and ____________ can disrupt circadian rhythms.

Question 4

Explain why the circadian rhythm is important.

Answers appear in the Self Test section of the book.