14.4 Central Banks

A central bank is an institution that oversees and regulates the banking system and controls the monetary base.

Who decides how large the monetary base will be? For all developed economies, the answer is the central bank—an institution that oversees and regulates the banking system and controls the monetary base. Canada’s central bank is the Bank of Canada. Other central banks include the Bank of England; the Federal Reserve, of the United States; the Bank of Japan; and the European Central Bank (ECB). The ECB acts as a common central bank for 17 European countries: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. The world’s oldest central bank, by the way, is Sweden’s Sveriges Riksbank, which awards the Nobel Prize in economics.

The Functions of a Central Bank

In some ways, central banks are just like ordinary banks: they accept deposits and give loans; they have assets and liabilities; and generally they make a profit. But unlike commercial banks, their clientele are not members of the public—

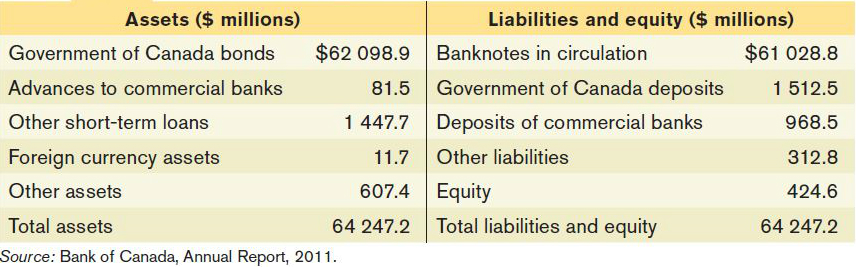

As with other central banks, the Bank of Canada accepts deposits from, and makes loans to, both the federal government and domestic commercial banks. Deposits from commercial banks are part of the Bank of Canada’s reserves. The BOC makes loans to both the government and the commercial banks by buying government bonds. Its greatest asset is Government of Canada bonds and its greatest liability is banknotes in circulation. The sum of the banknotes in circulation and deposits of commercial banks is the monetary base.

The following is a more detailed description of the central bank’s four major responsibilities.

1. The Central Bank Acts as Banker for Commercial Banks Just as you find it convenient to put your money in a bank and to write cheques on that account, so do commercial banks. Depositing cash with the central bank rather than holding cash reserves in their own vaults has another advantage for commercial banks: the central bank will, on order, transfer money from one bank’s account to the account of another bank. In this way, commercial bank accounts with the central bank can be used to settle large debts between the commercial banks with a single keystroke. The third row on the right side of Table 14-3 shows that the deposits of commercial banks with the Bank of Canada amounted to $968.5 million in December 2011. This money constitutes an asset owned by the commercial banks—

As banker for the commercial banks, a central bank is also committed to keeping the banking system stable. A central bank will normally act as a “lender of last resort” for a commercial bank with sound investments that is in urgent need of cash and cannot find a lender. More generally, a central bank will loan money on a daily basis to a commercial bank that is short of cash reserves, at a rate known as the bank rate. For example, the second row on the left side of Table 14-3 shows that in December 2011 the Bank of Canada lent $81.5 million to commercial banks for this reason. At the same time, the Bank of Canada made $1447.7 million in short-

2. The Central Bank Acts as Banker for the Federal Government The federal government also finds it convenient to put its money in a bank and to write cheques on that account. The second row on the right side of Table 14-3 shows that in December 2011, the federal government had $1512.5 million in its chequing account with the Bank of Canada. The federal government also has demand deposits at the large commercial banks, and it is the job of the Bank of Canada to manage these government bank accounts. When the government needs to borrow money, does the central bank lend it money? Yes, occasionally, but not always. When the government needs to borrow money it issues government securities—

3. The Central Bank Issues Currency It is a central bank’s duty to issue currency, prevent counterfeiting, and ensure that the supply of banknotes meets public demand. The top row on the right side of Table 14-3 shows that in December 2011 there were just over $61 billion in banknotes in circulation. These notes are a liability of the Bank of Canada. Before 1940, this liability was clear because these notes could be exchanged for gold. Even though that exchange is no longer in force, the Bank of Canada still has the duty to maintain the viability of these notes as legal tender.

4. The Central Bank Conducts Monetary Policy A central bank has the duty to conduct the nation’s monetary policy. This may involve controlling interest rates, the quantity of money, the exchange rate, or some combination of these actions. Since the central bank may occasionally intervene in foreign exchange markets to moderate fluctuations in the value of the Canadian dollar, it needs to hold some foreign currency. Before September 1998, the Bank of Canada’s policy was to automatically intervene in the foreign exchange market whenever the Canadian dollar came under significant upward or downward pressure. The BOC also undertook other interventions at its discretion whenever conditions merited it. The Asian financial crisis of 1997 created significant downward pressure on a number of currencies, and not just those of Asian countries. Countries that supplied commodities to these growing Asian countries, such as Canada, found their currencies caught in the downdraft. This contributed to the 1998 Russian financial crisis and default on Russian debt, which in turn caused the failure of the U.S. hedge fund Long-

The Structure of the Bank of Canada

Now we know what central banks do, the next question is “Who controls them?” While all central banks are owned by their governments, most have a degree of autonomy from their government, essentially because it is desirable to separate the power to spend (which the government has) from the power to print money (which the central bank has).

With respect to the Bank of Canada, legally it is a crown corporation owned by the government. As such, any profit it makes is remitted to the government. But despite being owned by the government, it is far from being a typical government department. Just like most central banks, the Bank of Canada is a partially independent institution with considerable autonomy to carry out its responsibilities. This partial autonomy is reflected in its institutional structure.

The Bank of Canada’s chief executive officer—

As we said, the Bank of Canada is only partially autonomous: the government still has considerable influence over it. The minister of finance appoints all members of the Board of Directors, and the federal cabinet must approve the governor’s appointment. Also, the minister of finance meets with the governor regularly to express the government’s desires regarding monetary policy. If a disagreement over policy occurs, the government can issue written instructions to the governor. If the governor feels these instructions are inappropriate and does not wish to implement them, then the governor must resign (or be fired).

Ultimately, the governor’s real power rests with the threat of his or her resignation. When a respected central banker resigns, the world takes notice. Everyone will suspect the government of trying to force unsound and inappropriate monetary policies onto its central bank. In itself this would cause considerable financial uncertainty. The governor of the BOC can use this power to influence monetary policy.

Central Banks’ Tools of Monetary Control

In general, central banks have four main tools for monetary control at their disposal: reserve requirements, the bank rate (or the discount rate), open-

Reserve Requirements Reserve requirements influence how much money the banking system can create with each dollar of reserves. If reserve requirements increase, banks can loan out less of each dollar that is deposited. This lowers the money multiplier and decreases the money supply. Many countries, such as Russia and Turkey, do have reserve requirements, but as noted earlier, Canadian banks do not. As a result, they hold amounts that are consistent with their desire to maximize profits and their experience of sound banking practice. Currently, the voluntary reserve ratio of Canadian banks is around 4%, and on occasions even lower.

The Bank Rate Occasionally, Canadian banks will find themselves short of reserves. On any given day individuals and firms write a great many cheques to finance their purchases. When these cheques are cleared at the end of the day, some banks may gain deposits and some may lose. As we discussed above, settlements between commercial banks can be made with a single keystroke by the Bank of Canada.

The overnight funds market is a financial market in which financial institutions, such as banks that are short of reserves can borrow funds from banks with excess reserves.

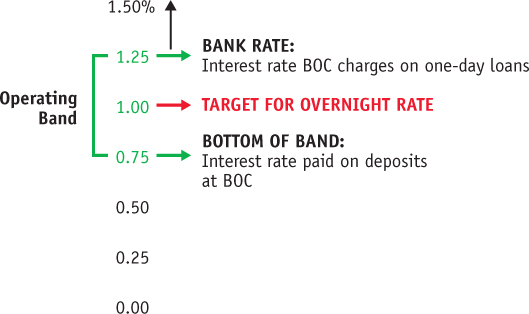

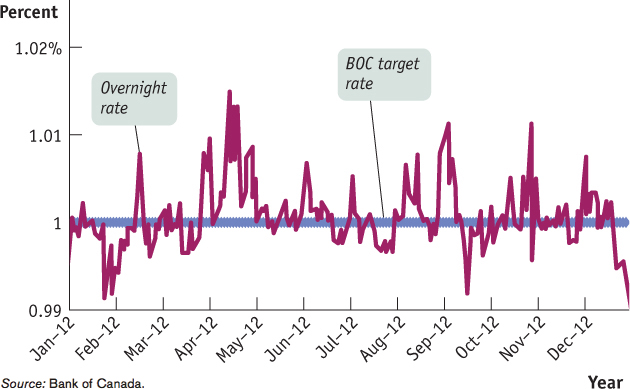

But what happens if a commercial bank doesn’t have enough in its deposit account with the Bank of Canada to settle its debts? Normally, a bank will borrow additional reserves from other banks. Banks lend money to each other in the overnight funds market, at the overnight rate of interest. The overnight funds market is a financial market that allows banks to borrow reserves from each other, usually just overnight. The interest rate in this market is called the overnight rate and is determined by supply and demand, both of which are strongly affected by Bank of Canada actions. As we’ll discuss in Chapter 15, the BOC has a target for the overnight rate called (appropriately enough) the target for the overnight rate. The BOC tries to ensure that the overnight rate stays within a band of half a percentage point of its target; that is, the overnight rate could be a quarter of a percentage point above or below the target. As we’ll see in the following Economics in Action, the BOC tends to hit its target almost precisely.

The overnight rate is the interest rate determined in the overnight funds market.

The target for the overnight rate is the Bank of Canada’s official key policy interest rate.

The bank rate is the rate of interest the Bank of Canada charges on loans to banks. In many countries, this rate of interest is known as the discount rate.

If a bank cannot borrow from other banks in the overnight funds market, it can always borrow from the Bank of Canada, at the bank rate. The bank rate (or the discount rate in some countries) is the rate of interest the BOC charges banks. The bank rate is set as the upper limit of the BOC’s operating band for the target for the overnight rate. So, the bank rate is one quarter of a percentage point above the target for the overnight rate.

Incidentally, the lower limit of the BOC’s operating band for the overnight rate target is the rate of interest it pays to commercial banks on their accounts (at the BOC). Figure 14-7 illustrates the relationship between the overnight rate, its target, and the upper and lower limits of the band.

If it chooses to do so, the Bank of Canada can change the target for the overnight rate (which would also change the bank rate) and so affect the money supply. If the Bank of Canada were to reduce the target for the overnight rate, banks would increase their lending because the cost of finding themselves short of reserves wouldn’t be as high, and as a result the money supply would increase. If the Bank of Canada were to increase the target for the overnight rate, bank lending would fall, as would the money supply.

An open-market operation is the purchase or sale of assets by a central bank. For the Bank of Canada, normally these assets are Government of Canada bonds, but they may also be foreign exchange.

Nowadays, the target for the overnight rate is the Bank of Canada’s main monetary policy tool. When the BOC changes this target, it is sending a clear signal about the direction in which it wants short-

Open-Market Operations

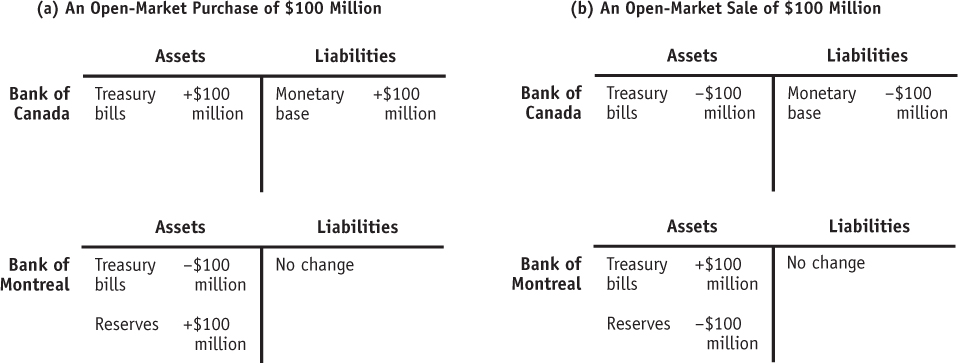

Another method central banks use to manage the money supply is open-

Suppose the Bank of Canada buys $100 million in bonds. It can pay for them using cash if it buys the bonds from the public, in which case banknotes in circulation increase by $100 million. If it buys the bonds from commercial banks, it can credit their accounts at the BOC by $100 million (i.e., bank reserves increase by $100 million). Either way, the monetary base has increased by $100 million. As seen in the previous section, this increases the money supply by a multiple of this $100 million and will shift the aggregate demand curve to the right.

Now let’s have a more specific example. Suppose the Bank of Canada buys the bonds from the Bank of Montreal and pays for them by crediting the Bank of Montreal’s account at the Bank of Canada with $100 million. Figure 14-9a shows the resulting changes in the financial positions of both institutions. The top of the figure shows the Bank of Canada now has $100 million more assets, consisting of government bonds, and $100 million more in liabilities, consisting of deposits owned by commercial banks—

Up to this point the money supply hasn’t been affected. However, the Bank of Montreal now has additional reserves. Since the Bank of Montreal earns more from lending money out to clients than having it sit in its account with the Bank of Canada, it will loan this money out. Suppose it loans all of the money. Then, the Bank of Montreal will credit individuals’ accounts by an extra $100 million, which they will eventually spend. Some of this money will be deposited back in the banking system, increasing reserves again and permitting a further round of loans, and so on. So an open-

Would the process differ if the Bank of Canada bought the bonds from a private individual using cash? Not substantively. The changes to the Bank of Canada’s balance sheet would be almost identical. Its assets and liabilities would both increase by $100 million. The only slight difference is that on the liability side of the ledger it would be “banknotes in circulation” that increase by $100 million rather than “deposits of commercial banks.” At this point the money supply has increased by $100 million. However, as soon as the private individual deposits the money in a commercial bank, that bank will find that its deposits and reserves have both increased by $100 million. Apart from the size of the deposit, this process is identical to that described in Table 14-1. In just the same way, the money multiplier process is again set in motion.

Conversely, as Figure 14-9b shows, an open-

Open-

Of course, the Bank of Canada doesn’t often buy (or sell) office furniture. However, there is one other asset (besides bonds) that it does sometimes buy and sell, and that is foreign currency. Suppose the Canadian dollar is appreciating (increasing in value) relative to the U.S. dollar, and this increase is affecting our exports negatively. To prevent the Canadian dollar from appreciating further, the BOC would sell Canadian dollars on the foreign exchange market, receiving foreign currency in exchange. In effect, the BOC is buying foreign currency using Canadian dollars. The BOC’s balance sheet would show an increase in assets, in the form of foreign currency, and an increase in liability in the form of banknotes in circulation. Since Canada is the only place where these Canadian dollars can be spent, they will eventually find their way into the deposits of commercial banks, leading to a multiple expansion of the money supply. In effect, the BOC has made an open-

WHO GETS THE INTEREST ON THE BANK OF CANADA’S ASSETS?

As we’ve just learned, the Bank of Canada owns a lot of assets—

The answer is, you do—

We can now finish the chapter’s opening story—

Meanwhile, the BOC decides on the size of the monetary base based on economic considerations—

In contrast, suppose the BOC wishes to prevent the Canadian dollar from depreciating (decreasing in value). Then it would buy Canadian dollars on the foreign exchange market using its foreign currency reserves. Since the Canadian dollars it buys are no longer in private use, the monetary base is reduced. The BOC’s balance sheet side would show a decrease in assets in the form of foreign currency, and a decrease in liability in the form of banknotes in circulation. In effect, the Bank of Canada has made an open-

The key point to all of this is that any attempt the Bank of Canada makes to influence the value of the Canadian dollar necessarily affects the supply of money. An independent monetary policy is possible only when the BOC allows market forces to determine the exchange rate, with no intervention of any sort on its part. Such a policy is called allowing the exchange rate to “float,” or a “floating exchange rate.” The analogy is to a boat, floating on the sea, buffeted by the waves, moving up and down with the swell.

Similarly, the value of the Canadian dollar, floating on the international exchange market, is buffeted by the forces of demand and supply, appreciating and depreciating as the market sees fit. When the exchange rate is allowed to float, the central bank is under no obligation to make any trades in the foreign exchange market. In this case, open-

The opposite of a floating exchange rate is a “fixed” exchange rate. When the exchange rate is fixed, the BOC must continually intervene in the foreign exchange market to offset those market forces that would otherwise tend to change the value of the Canadian dollar. It does this through buying and selling foreign currency—

We’ll talk more about exchange rates in Chapter 19. For now, our bottom line is this: a fixed exchange rate is inconsistent with independent monetary policy. A floating exchange rate is what permits independent monetary policy.

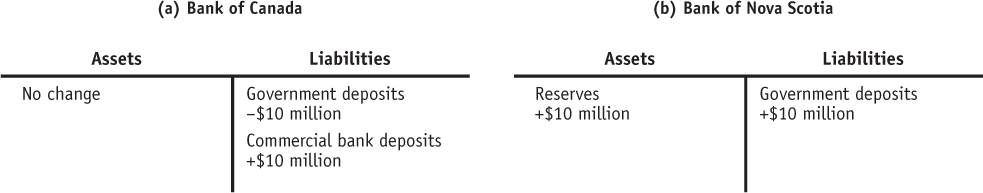

Deposit switching is the shifting of government deposits between the Bank of Canada and the commercial banks. It is a major tool used by the Bank of Canada in its day-

Deposit Switching In addition to open-

Suppose, for example, that the Bank of Canada transfers $10 million from the government’s account at the Bank of Canada to the government’s account at the Bank of Nova Scotia. The transactions involved are illustrated in Figure 14-10. From the government’s point of view, nothing has changed. However, the Bank of Nova Scotia finds that its deposit liabilities and reserves have each increased by $10 million. With an unchanged desired reserve ratio, the Bank of Nova Scotia will have excess reserves, and will begin expanding its loans and creating more deposit money.

Similarly, a switch of government deposits away from chartered banks depletes their reserves—

Economists often say, loosely, that the Bank of Canada controls the money supply. Actually, it controls only the monetary base. But by increasing or reducing the monetary base, the Bank of Canada can exert a powerful influence on both the money supply and interest rates. This influence is the basis of monetary policy, the subject of our next chapter.

Interest Rate Targets versus Money Supply Targets

In the next chapter, we’ll see that all central banks have to make a choice: they can either set the money supply and let the interest rate adjust, or they can set a key interest rate and then adjust the money supply to accommodate the resulting change in desired money holdings. No central bank can set both the money supply and the interest rate independently or simultaneously. But which policy is better?

Currently, the Bank of Canada chooses to set a key interest rate. One reason for this is that the BOC can influence the money supply, but not control it. In other words, it is possible for the money supply to change without any deliberate change in monetary policy. For example, if households choose to hold more cash, the commercial banks will have less cash to hold as reserves, so the money supply will decrease. Or, if commercial banks feel that the economic environment is too risky, they may choose to increase their desired reserve ratio, and again the money supply will decrease.

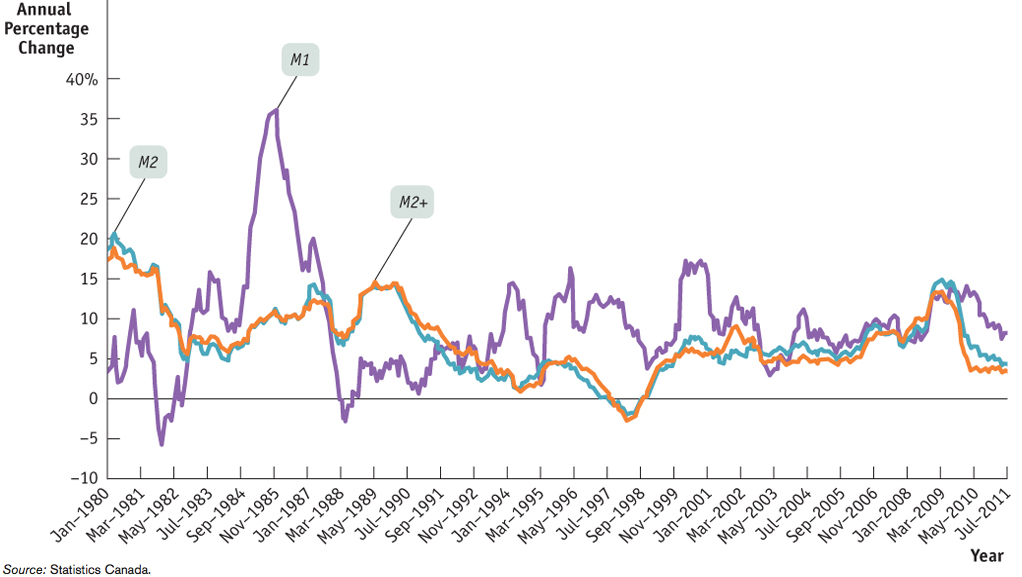

There is another, more fundamental reason why the BOC can’t completely control the money supply: it’s not clear what the money supply is. As we have seen, there are several measures of the money supply, including M1, M2, and M2+, which differ in magnitude and in their annual growth rates. At any given time, some measures of the money supply may be increasing, and others may be decreasing. Figure 14-11 shows the annual percentage change in M1, M2, and M2+ from January 1980 to July 2011. It is obvious that, while these different monetary aggregates are highly correlated, their growth rates do not necessarily move together perfectly, let alone even move in the same direction all the time.

But while the BOC may not be able to control the money supply, it can control its key policy interest rate—

There is another advantage in setting the interest rate instead of the money supply: changes in interest rates tend to be more meaningful to firms and households. For example, if mortgage lending rates at commercial banks have decreased by one percentage point, we can readily understand what this means for our plans to buy a new house. By contrast, if we hear that the money supply has just increased by $5 billion, it is not clear what this means.

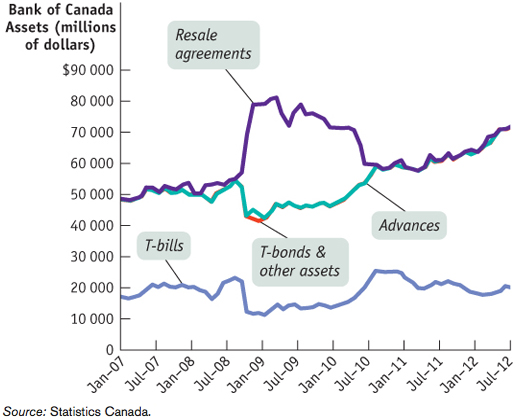

THE BANK OF CANADA’S BALANCE SHEET, NORMAL AND ABNORMAL

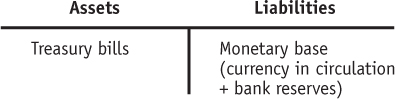

Figure 14-8 showed a simplified version of the BOC’s balance sheet. As Figure 14-8 indicated, the liabilities consisted entirely of the monetary base and assets consisted entirely of treasury bills. Of course, in reality, the BOC’s balance sheet is much more complicated. But, normally, Figure 14-8 is a reasonable approximation: the monetary base typically accounts for more than 90% of the BOC’s liabilities, and almost all its assets are in the form of claims on the Government of Canada (as in Canadian government treasury bills and bonds).

But in late 2007 it became painfully clear that we were no longer in normal times. The source of the turmoil was the bursting of a huge housing bubble in the United States, described in Chapter 10, which led to massive losses for some financial institutions that had made U.S. mortgage loans or held U.S. mortgage-

As we’ll describe in more detail in the next section, not only standard deposit-

The U.S. Federal Reserve (the American central bank, known as “the Fed”) sprang into action to contain what was becoming a meltdown across the entire financial sector. It greatly expanded its discount window—

As the financial crisis spread around the globe, central banks worldwide found they too faced similar, albeit generally smaller, crises of confidence in their own banks and financial markets. The result was a spread of the freeze-

Examining Figure 14-13, we see that starting in the fall of 2008, the BOC sharply reduced its holdings of traditional securities like treasury bills, as its lending to financial institutions skyrocketed. “Advances” refer to loans from lenders of last resort made at the bank rate. “Resale agreements” cover purchases by the BOC of assets like mortgages and corporate bonds, which were necessary to keep interest rates on loans to firms from soaring.

By late 2009, the crisis began to subside, but the BOC didn’t return to its traditional asset holdings. Instead, it continued to offer substantial amounts of loans via resale agreements throughout much of 2010 and increased its holding of longer-

Quick Review

The Bank of Canada is Canada’s central bank, overseeing the banking system and making monetary policy. Although owned by the federal government, the Bank of Canada is partially autonomous.

Banks borrow and lend reserves in the overnight funds market. The interest rate determined in this market is the overnight rate. Banks can also borrow from the Bank of Canada at the bank rate (also known as the discount rate in some countries).

The Bank of Canada’s key policy interest rate is its target for the overnight rate. This is the overnight interest rate the BOC would like to see occur in the market. To achieve this target, the BOC usually controls the level of reserves in the banking system by open-market operations or by switching government deposits between itself and the chartered banks; that is, by deposit switching.

The Bank of Canada no longer sets a required reserve ratio for banks. If the BOC wishes to alter the amount of reserves, it changes the bank rate, using the same techniques, open-

market operations and deposit switching. When the Bank of Canada buys bonds on the open market or switches government deposits into commercial banks, it increases the reserves in the banking system, which in turn increases the monetary base and the money supply. In contrast, when the BOC sells bonds or switches government deposits from commercial banks to itself, it decreases the reserves, which in turn reduces the monetary base and the money supply.

Check Your Understanding 14-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14-4

Assume that any money lent by a bank is always deposited back in the banking system as a chequeable deposit and that the reserve ratio is 10%. Trace out the effects of a $100 million open-

market purchase of treasury bills by the Bank of Canada on the value of chequeable deposits. What is the size of the money multiplier?

An open-