The Economics of the Book Industry

To serve customers profitably, the book business (like other mass media industries) must bring in money while also investing in needed resources. Publishers make money by selling books through specific channels (such as brick-and-mortar stores and online stores) and by selling television and movie rights; publishers spend money on essential activities such as book production, distribution, and marketing.

Money In

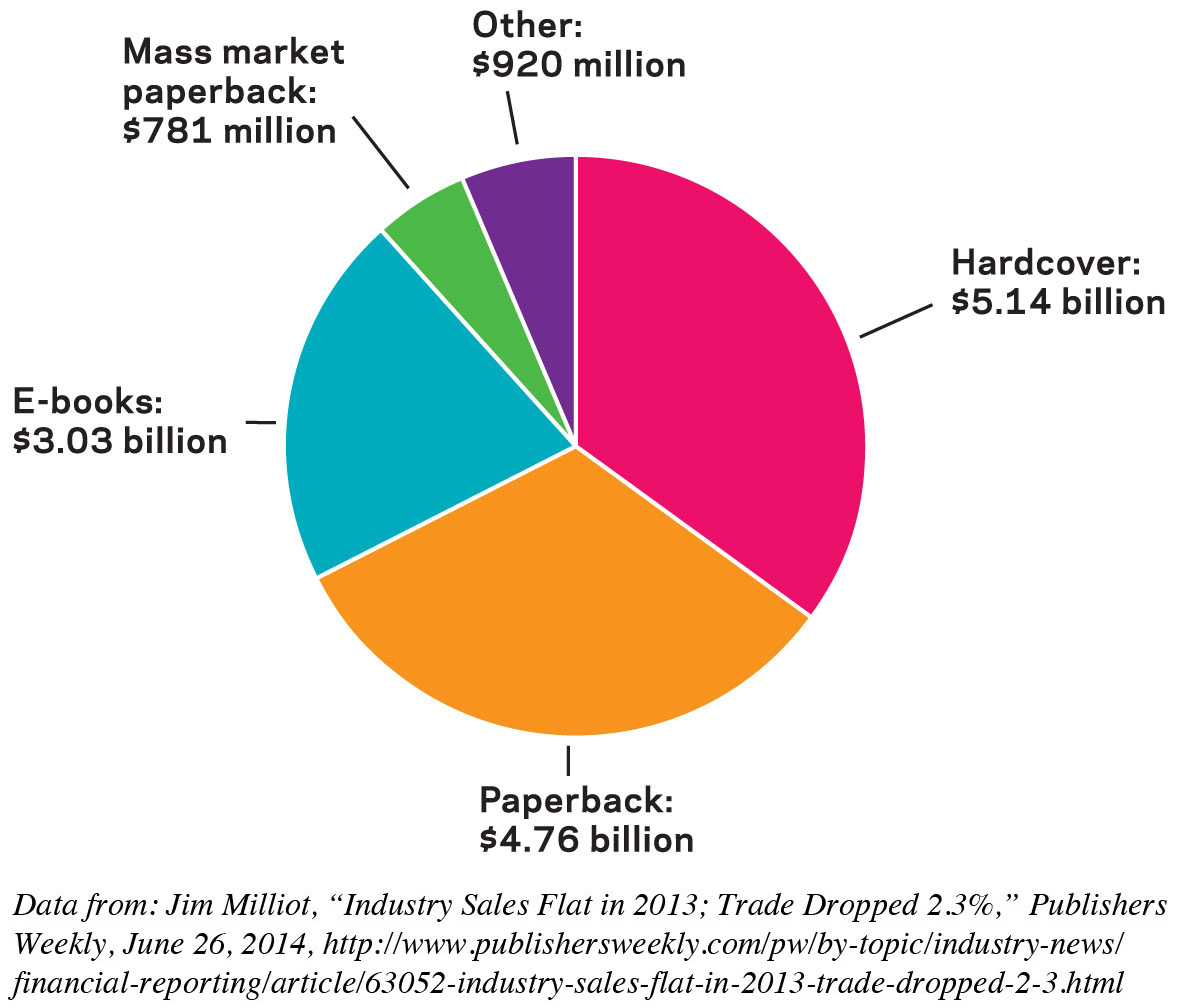

Compared with other mass media industries, book publishing has seen only a relatively modest increase in revenues over the decades. From the mid-1980s to 2013, total revenues went from $9 billion to about $27 billion (see Figure 2.2), but the industry continues to seek new and bigger sources of growth. Publishers bring in money through a variety of channels.

Book Sales

The most obvious source of revenue for publishers is sales of the books themselves—whether they’re in print, audio, or e-book form. There are several main outlets for selling books:

Brick-and-mortar stores. These include traditional bookstores, department stores, drugstores, used-book stores, and toy stores. Since the 2011 bankruptcy of Borders, the single largest chain—Barnes & Noble—now dominates book sales. Barnes & Noble operates 661 superstores and 700 college bookstores, though it closed its last remaining B. Dalton bookstores in 2010. The rise of book superstores—along with competition from online stores—severely cut into independent bookstores’ business, dropping their number from 5,100 in 1991 to only about 1,900 today. Many independents have formed regional or statewide groups to develop survival tactics.

Amazon’s warehouses go far beyond the stockrooms of typical brick-and-mortar stores, housing more than one hundred employees in each location, of which there are dozens across the United States and throughout the world.David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Amazon’s warehouses go far beyond the stockrooms of typical brick-and-mortar stores, housing more than one hundred employees in each location, of which there are dozens across the United States and throughout the world.David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty ImagesOnline stores. Since the late 1990s, online booksellers have created an entirely new book-distribution system on the Internet. The trailblazer is Amazon.com, established in 1995 by then thirty-year-old Jeff Bezos. In 1997, Barnes & Noble, the leading retail store bookseller, launched its own heavily invested and carefully researched bn.com site. In 1999, the ABA launched BookSense.com to help more than a thousand independent bookstores establish an online presence. Despite this competition, Amazon remains the top online retailer, controlling 41 percent of U.S. book sales by 2014 (print and e-books combined).10 The strength of online sellers lies in their convenience and low prices, especially their ability to offer backlist titles and the works of less-famous authors that even superstores don’t carry on their shelves. Many online customers also appreciate the ability to post their own book reviews at online stores, read those of fellow customers, and receive book recommendations based on their searches and past purchases. As book readers turn to e-books, online stores are better situated for this transition. By 2011, customers were buying more e-books than print books from Amazon.

Book clubs. Similar to music clubs, book clubs entice new members with introductory offers, such as five books for a dollar, then require regular purchases from their list of recommended titles. The Book-of-the-Month Club and the Literary Guild are two examples, both launched in 1926. Originally, this business model helped generate revenues when bookstores were not as numerous as they are today. But since the 1980s, book clubs’ sales have declined. Today, twenty remaining book clubs—including the Book-of-the-Month Club, the Literary Guild, and Doubleday—are consolidated under a single company, Pride Tree Holdings, which also owns DVD and music clubs.

Mail order. Mail-order bookselling was another tactic introduced before bookstores became a major channel for selling, now used primarily by trade, professional, and university press publishers. Like a book club, a mail-order company immediately notifies readers about new book titles. This channel appeals to customers who want to avoid the hassle of shopping in stores or who want their purchases (for example, of sexually explicit materials) to remain private.

Regardless of what channel a publisher sells its books through, trade publishers are constantly on the hunt for the next best-seller—dating back to the huge success of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which sold 15,000 copies in just fifteen days in 1852. (A total of three million copies flew off the shelves before the Civil War.) A best-seller can come from anywhere—a celebrity who pens his or her autobiography, a respected scientist who offers a provocative new perspective on artificial intelligence, a first-time novelist whose work is chosen for Oprah’s Book Club.

Indeed, publishers have learned that TV can help sell books. Through TV exposure, books by or about talk-show hosts, actors, and politicians sell millions of copies—enormous sales in a business in which 100,000 units sold constitutes remarkable success. In national polls conducted from the 1980s through today, nearly 30 percent of respondents said they had read a book after seeing a story about it or a promotion on television. A major force in promoting books on TV was Oprah’s Book Club. Each selection by the club—before it made its transition online to Oprah’s Book Club 2.0 in 2012—became an immediate best-seller.

TV and Movie Rights

One of the most dramatic (literally and figuratively) examples of media convergence happens in the relationship between book publishing and the big (and little) screens. Many TV shows and films get their story ideas from books, a process that generates enormous movie-rights revenues for the book industry and its authors. The most profitable movie-rights deals for the book industry in recent years have included the Hunger Games and Harry Potter series as well as Peter Jackson’s movie adaptations of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (first published in the 1950s). The subgenre of comic books and graphic novels has led to countless films on its own, including several top box-office hits, like the Dark Knight trilogy and Marvel’s interconnected series of superhero films. And just as a popular book can help generate interest for a movie, a movie or TV show can boost book sales. HBO’s adaptation of A Game of Thrones, the first book in George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, pushed Martin’s work to the top of best-seller lists and promoted the publication of the fifth book in the series, A Dance with Dragons. TV or movie promotion can also boost sales in new media: In September 2011, Martin joined Amazon’s Kindle Million Club, meaning that e-book sales of his work have exceeded one million downloads. Even classic and public domain books (those no longer subject to copyright law) can create profits for the book industry. For example, in 2011, a screen version of Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel Jane Eyre boosted sales of the reissued novel.

Money Out

To generate sales, publishers must spend money on producing books, distributing their products, and promoting or marketing newly launched titles.

Based On: Making Books into Movies

Writers and producers discuss the process that brings a book to the big screen.

Discussion: How is the creative process of writing a novel different from that of making a movie? Which would you rather do, and why?

Production

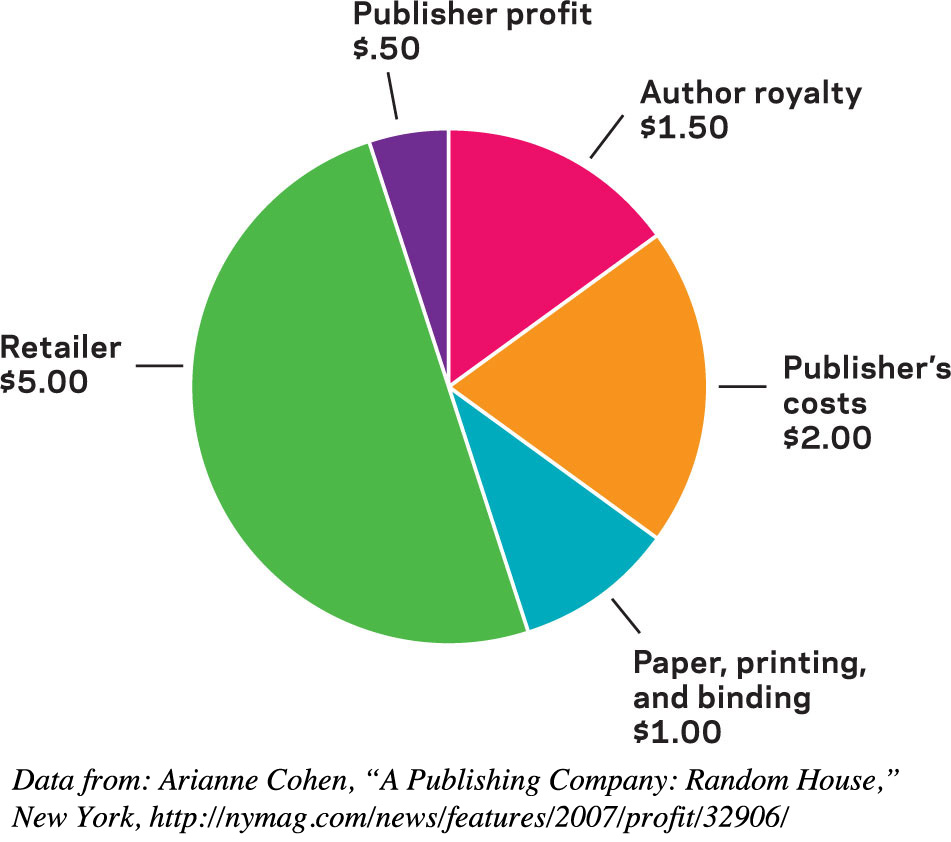

To produce books, publishing houses have expenditures such as overhead (including salaries for the employees who edit and design books) as well as paper, printing, and binding. Also, as part of their contracts, authors sometimes require that publishers pay them advance money, an up-front payment that’s subtracted from royalties later earned from book sales (see Figure 2.3). Typically, an author’s royalty is 5 to 15 percent of the net price of the book. New authors may receive little or no advance from a publisher, but commercially successful authors can receive millions. For example, Interview with a Vampire author Anne Rice hauled in a $17 million advance from Knopf in a contract for writing three more vampire novels. Celebrities such as actors, musicians, or politicians can also get million-dollar advances. In 2012, Girls writer, director, and star Lena Dunham got a $3.5 million advance for her book. J.K. Rowling got a reported $8 million advance for her 2012 book, The Casual Vacancy.

Distribution

Distribution costs include maintaining inventory of books to be sold and fulfilling orders (shipping books to commercial outlets or college bookstores). Publishers monitor their warehouse inventories to ensure that enough copies of a book will be available to meet demand. Anticipating demand, though, is a tricky business. No publisher wants to be caught short if a book proves more popular than originally predicted. Nor does it want to get stuck with books it can’t sell, as the company must then absorb the cost of returned books. As one way to avoid both of these costly scenarios, distributors, publishers, and bookstores have begun taking advantage of digital technology to print books on demand rather than stockpiling them in warehouses. Through this technology, they can revive books that would otherwise have gone out of print because of limited demand—and avoid the expense of carrying unsold books (see “Converging Media Case Study: Self-Publishing Redefined”).

Marketing

Publishers spend a significant amount of money on marketing, which includes advertising and generating favorable reviews. For trade books and some scholarly books, publishing houses may send advance copies of a book to appropriate magazines and newspapers with the hope of receiving positive reviews that can be used in promotional materials, such as brochures. A house may also send well-known authors on book-signing tours and arrange radio and TV talk-show interviews to promote their books. College textbook firms “seed adoptions” by paying instructors an honorarium to review a book that’s in development, by sending free examination copies to potential adopters, and by promoting new titles through direct-mail brochures.

To help create a best-seller, trade publishing houses often give large illustrated cardboard bins, called dumps, to bookstores to display a particular book in bulk quantities. Large trade houses buy shelf space from major chains to ensure prominent locations in bookstores. Publishers also buy ad space in newspapers and magazines and on buses, billboards, television, radio, and the Web—all to pump up interest in a new book.