Chapter 11 Introduction

CHAPTER 11

One-

Type I Errors When Making Three or More Comparisons

The F Statistic as an Expansion of the z and t Statistics

The F Distributions for Analyzing Variability to Compare Means

The F Table

The Language and Assumptions for ANOVA

Everything About ANOVA but the Calculations

The Logic and Calculations of the F Statistic

Making a Decision

R2, the Effect Size for ANOVA

Post Hoc Tests

Tukey HSD

The Benefits of Within-

The Six Steps of Hypothesis Testing

R2, the Effect Size for ANOVA

Tukey HSD

BEFORE YOU GO ON

You should understand the z distribution and the t distributions. You should also be able to differentiate among distributions of scores (Chapter 6), means (Chapter 6), mean differences (Chapter 9), and differences between means (Chapter 10).

You should know the six steps of hypothesis testing (Chapter 7).

You should understand what variance is (Chapter 4).

You should be able to differentiate between between-

groups designs and within- groups designs (Chapter 1). You should understand the concept of effect size (Chapter 8).

Here’s the bad news: You are not very good at multitasking. Here’s some additional bad news: You probably think you’re pretty good at multitasking—

Usually, nothing bad happens when you drive and talk on your mobile phone, so many people probably conclude that they are pretty good at multitasking while driving. But here’s a simple research question: Are we worse drivers when we talk on a hands-

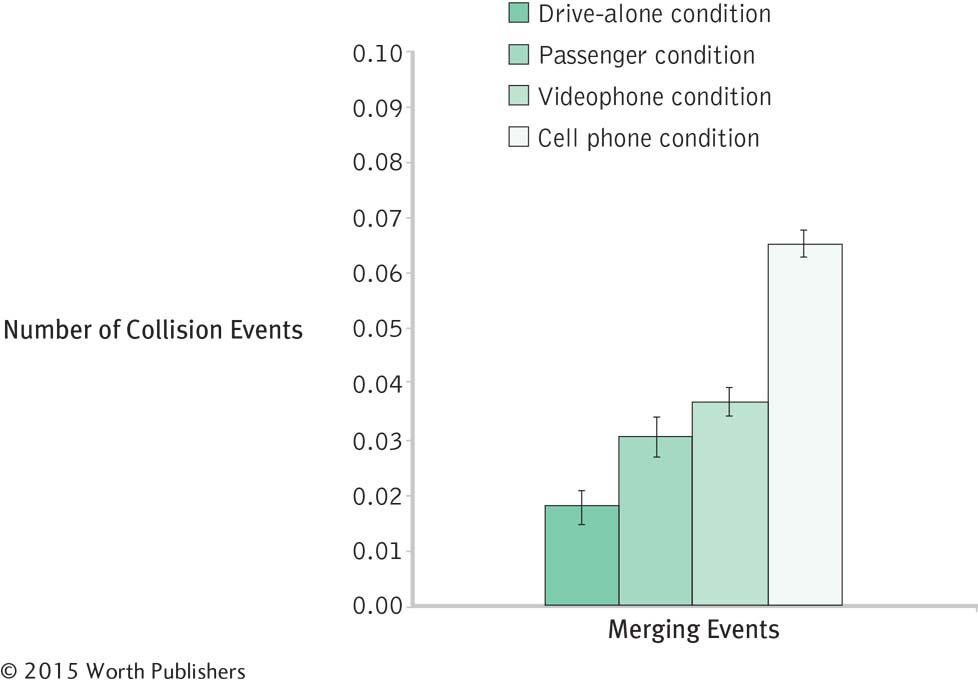

To address the variety of conversations, researchers used a driving simulator with eight surrounding projection screens to create a series of dangerous driving situations, such as merging into traffic (Gaspar & colleagues, 2014). Participants experienced all four different experimental conditions: (1) driving alone, (2) driving and talking with a passenger seated next to them, (3) driving and talking on a videophone with a “remote passenger” in a separate room, and (4) driving and talking on a hands-

Comparing Three or More Groups

Researchers compared four groups in one study, which allowed them to discover that a conversation on a hands-

For researchers, a four-