Chapter Introduction

Appendix A

Statistical Reasoning in Everyday Life

Measures of Central Tendency

Measures of Variation

Correlation: A Measure of Relationships

When Is an Observed Difference Reliable?

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT: Cross-

When Is an Observed Difference “Significant”?

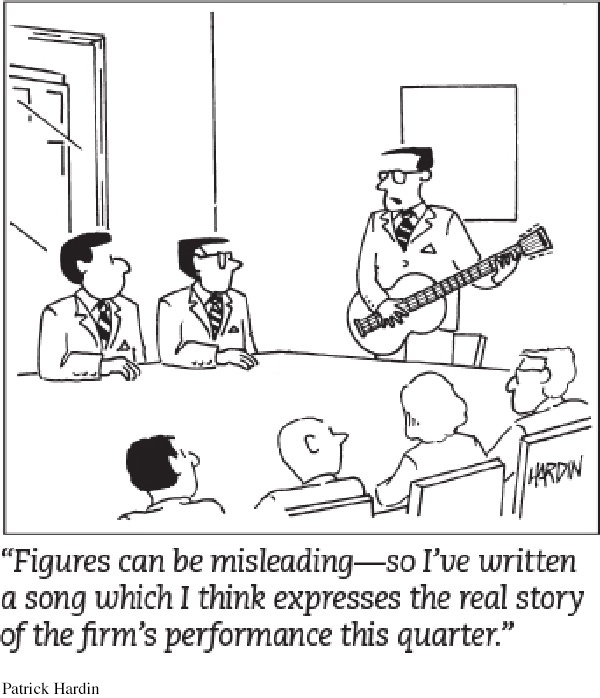

Statistics are important tools in psychological research. But accurate statistical understanding benefits everyone. To be an educated person today is to be able to apply simple statistical principles to everyday reasoning. We needn’t memorize complicated formulas to think more clearly and critically about data.

Off-

When setting goals, we love big, round numbers. We’re far more likely to want to lose 20 pounds than 19 or 21 pounds. And by modifying their behavior, batters are nearly four times more likely to finish the season with a .300 average than with a .299 average (Pope & Simonsohn, 2011).

Ten percent of people are gay or lesbian. Or is it 2 to 4 percent, as suggested by various national surveys (Chapter 4)?

We ordinarily use only 10 percent of our brain. Or is it closer to 100 percent (Chapter 2)?

The human brain has 100 billion nerve cells. Or is it more like 86 billion, as suggested by one analysis (Chapter 2)?

The point to remember: Doubt big, round, undocumented numbers.

Statistical illiteracy also feeds needless health scares (Gigerenzer, 2010; Gigerenzer et al., 2008, 2009). In the 1990s, the British press reported a study showing that women taking a particular contraceptive pill had a 100 percent increased risk of blood clots that could produce strokes. This caused thousands of women to stop taking the pill, leading to a wave of unwanted pregnancies and an estimated 13,000 additional abortions (which also are associated with increased blood clot risk). And what did the study actually find? A 100 percent increased risk, indeed—