1.4 How Do Psychologists Ask and Answer Questions?

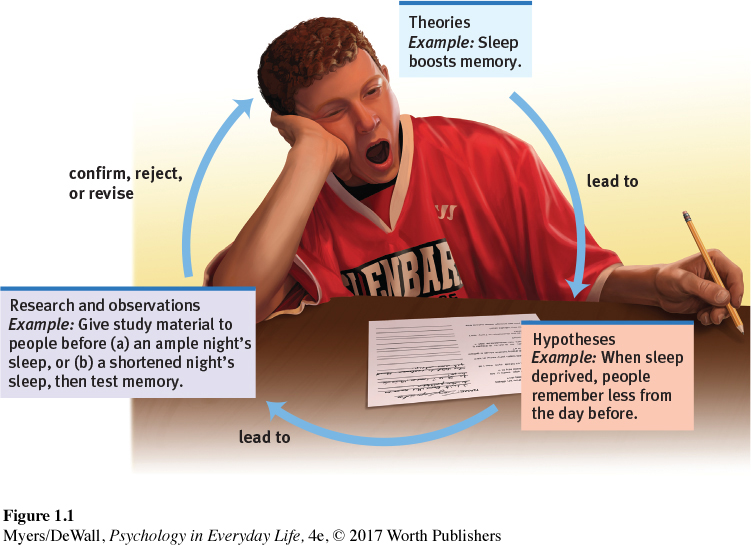

Psychologists try to avoid the pitfalls of intuitive thinking by using the scientific method. They observe events, form theories, and then refine their theories in the light of new observations.

The Scientific Method

LOQ 1-

theory an explanation using principles that organize observations and predict behaviors or events.

Chatting with friends and family, we often use theory to mean “mere hunch.” In science, a theory explains behaviors or events by offering ideas that organize what we have observed. By organizing isolated facts, a theory simplifies. There are too many facts about behavior to remember them all. By linking facts to underlying principles, a theory offers a useful summary. It connects many small dots so that a clear picture emerges.

A theory about the effects of sleep on memory, for example, helps us organize countless sleep-

hypothesis a testable prediction, often implied by a theory.

Yet no matter how reasonable a theory may sound—

Our theories can bias our observations. The urge to see what we expect to see is always present, both inside and outside the laboratory. Having theorized that better memory springs from more sleep, we may see what we expect: We may perceive sleepy people’s comments as less insightful.

operational definition a carefully worded statement of the exact procedures (operations) used in a research study. For example, human intelligence may be operationally defined as what an intelligence test measures.

replication repeating the essence of a research study, usually with different participants in different situations, to see whether the basic finding can be reproduced.

As a check on their biases, psychologists use operational definitions when they report their studies. “Sleep deprived,” for example, may be defined as “2 or more hours less” than the person’s natural sleep. These exact descriptions will allow anyone to replicate (repeat) the research. Other people can then re-

Replication is an essential part of good science. When 270 psychologists recently worked together to redo 100 psychological studies, the results made news: Only 36 percent of the results were replicated (Open Science Collaboration, 2015). (None of the nonreproducible findings appears in this text.) But then another team of scientists found most of the failed replications flawed and “the reproducibility of psychological science” to be “quite high” (Gilbert et al., 2016).Other fields, including medicine, also have seeming issues with nonreplicated findings (Collins & Tabak, 2014). Especially when based on a small sample, a single failure to replicate can itself need replication (Maxwell et al., 2015). In all scientific fields, replication either confirms findings, or enables us to correct or refine our knowledge.

“Failure to replicate is not a bug; it is a feature. It is what leads us along the path–

Lisa Feldman Barrett, “Psychology Is Not in Crisis,” 2015

Let’s summarize. A good theory:

effectively organizes a range of self-

reports and observations. leads to clear predictions that anyone can use to check the theory or to create practical applications of it.

often stimulates replications and more research that supports the theory (as happened with sleep and memory studies, as you’ll see in Chapter 2), or leads to a revised theory that better organizes and predicts what we observe.

We can test our hypotheses and refine our theories in several ways.

Descriptive methods describe behaviors, often by using (as we will see) case studies, naturalistic observations, or surveys.

Correlational methods associate different factors. (You’ll see the word factor often in descriptions of research. It refers to anything that contributes to a result.)

Experimental methods manipulate, or vary, factors to discover their effects.

To think critically about popular psychology claims, we need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of these methods. (For more information about some of the statistical methods that psychological scientists use in their work, see Appendix A, Statistical Reasoning in Everyday Life.)

Retrieve + Remember

Question 1.7

•What does a good theory do?

ANSWER: 1. It organizes observed facts. 2. It implies hypotheses that offer testable predictions and, sometimes, practical applications. 3. It often stimulates further research.

Question 1.8

•Why is replication important?

ANSWER: When others are able to repeat (replicate) studies and produce similar results, psychologists can have more confidence in the original findings.

Description

LOQ 1-

In daily life, we all observe and describe other people, trying to understand why they think, feel, and act as they do. Professional psychologists do much the same, though more objectively and systematically, using

case studies (in-

depth analyses of individuals or groups). naturalistic observations (watching and recording individual or group behavior in a natural setting).

surveys and interviews (self-

reports in which people answer questions about their behavior or attitudes).

The Case Study

case study a descriptive technique in which one individual or group is studied in depth in the hope of revealing universal principles.

A case study examines one individual or group in depth, in the hope of revealing things true of us all. Some examples: Medical case studies of people who lost specific abilities after damage to certain brain regions gave us much of our early knowledge about the brain. Jean Piaget, the pioneer researcher on children’s thinking, carefully watched and questioned just a few children. Studies of only a few chimpanzees jarred our beliefs about what other species can understand and communicate.

Intensive case studies are sometimes very revealing. They often suggest directions for further study, and they show us what can happen. But individual cases may also mislead us. The individual being studied may be atypical (not like those in the larger population). Viewing such cases as general truths can lead to false conclusions. Indeed, anytime a researcher mentions a finding (Smokers die younger: 95 percent of men over 85 are nonsmokers), someone is sure to offer an exception (Well, I have an uncle who smoked two packs a day and lived to be 89). These vivid stories, dramatic tales, and personal experiences command attention and are easily remembered. Stories move us, but stories—

The point to remember: Individual cases can suggest fruitful ideas. What is true of all of us can be seen in any one of us. But just because something is true of one of us (the atypical uncle), we should not assume it is true of all of us (most long-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 1.9

•We cannot assume that case studies always reveal general principles that apply to all of us. Why not?

ANSWER: Case studies focus on one individual or group, so we can’t know for sure whether the principles observed would apply to a larger population.

Naturalistic Observation

naturalistic observation a descriptive technique of observing and recording behavior in naturally occurring situations without trying to change or control the situation.

A second descriptive method records behavior in a natural environment. These naturalistic observations may describe parenting practices in different cultures, students’ self-

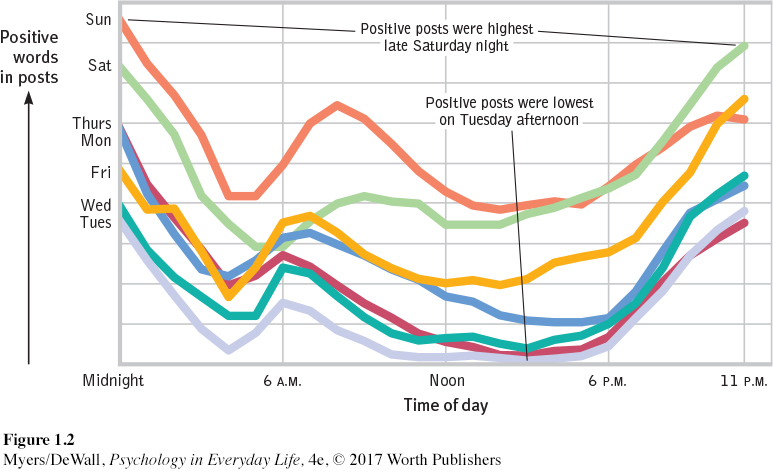

The scope of naturalistic observations is expanding. Until recently, naturalistic observation was mostly “small science”—possible with pen and paper rather than fancy equipment and a big budget (Provine, 2012). But new technologies have expanded the scope of naturalistic observations. The billions of people entering personal information on sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google have created a huge new opportunity for “big data” observations. To track the ups and downs of human moods, one study counted positive and negative words in 504 million Twitter messages from 84 countries (Golder & Macy, 2011). When were people happiest? As FIGURE 1.2 shows, spirits seemed to rise on weekends, shortly after waking, and in the evenings. (Are late Saturday evenings often a happy time for you, too?) Another study found that the proportion of negative emotion words (especially anger-

Smart-

Like the case study method, naturalistic observation does not explain behavior. It describes it. Nevertheless, descriptions can be revealing: The starting point of any science is description.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 1.10

•What are the advantages and disadvantages of naturalistic observation, such as the EARs study?

ANSWER: In the EARs study, researchers were able to carefully observe and record naturally occurring behaviors outside the artificial environment of a laboratory. However, they were not able to explain the behaviors because they could not control all the factors that may have influenced them.

The Survey

survey a descriptive technique for obtaining the self-

A survey looks at many cases in less depth, asking people to report their own behavior or opinions. Questions about everything from sexual practices to political opinions are put to the public. In recent surveys,

Saturdays and Sundays have been the week’s happiest days (confirming what the Twitter researchers found using naturalistic observation) (Stone et al., 2012).

1 in 5 people across 22 countries reported believing that alien beings have come to Earth and now walk among us disguised as humans (Ipsos, 2010).

68 percent of all humans—

some 4.6 billion people— say that religion is important in their daily lives (from Gallup World Poll data analyzed by Diener et al., 2011).

But asking questions is tricky, and the answers often depend on the way you word your questions and on who answers them.

WORDING EFFECTS Even subtle changes in the wording of questions can have major effects. Should violence be allowed to appear in children’s television programs? People are much more likely to approve “not allowing” such things than “forbidding” or “censoring” them. In one national survey, only 27 percent of Americans approved of “government censorship” of media sex and violence, though 66 percent approved of “more restrictions on what is shown on television” (Lacayo, 1995). People are much more approving of “aid to the needy” than of “welfare,” and of “revenue enhancers” than of “taxes.” Wording is a delicate matter, and some words can trigger positive or negative reactions. Critical thinkers will reflect on how a question’s phrasing might affect the opinions people express.

population all those in a group being studied, from which samples may be drawn. (Note: Except for national studies, this does not refer to a country’s whole population.)

random sample a sample that fairly represents a population because each member has an equal chance of inclusion.

RANDOM SAMPLING For an accurate picture of a group’s experiences and attitudes, there’s only one game in town. In a representative sample, a smaller group can accurately reflect the larger population you want to study and describe.

So how do you obtain a representative sample? Say you want to survey the total student population at your school to get their reaction to an upcoming tuition increase. To be sure your sample represents the whole student population, you will want to choose a random sample, in which every person in the entire population has an equal chance of being picked. You would not want to ask for volunteers, because those extra-

With very large samples, estimates become quite reliable. E is estimated to represent 12.7 percent of the letters in written English. E, in fact, is 12.3 percent of the 925,141 letters in Melville’s Moby-

Time and money will affect the size of your sample, but you would try to involve as many people as possible. Why? Because large representative samples are better than small ones. (But a smaller representative sample of 100 is better than a larger unrepresentative sample of 500.)

Political pollsters sample voters in national election surveys just this way. Using only 1500 randomly sampled people, drawn from all areas of a country, they can provide a remarkably accurate snapshot of the nation’s opinions. Without random sampling, large samples—

The point to remember: Before accepting survey findings, think critically. Consider the wording of the questions and the sample. The best basis for generalizing is from a random sample of a population.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 1.11

•What is an unrepresentative sample, and how do researchers avoid it?

ANSWER: An unrepresentative sample is a group that does not represent the population being studied. Random sampling helps researchers form a representative sample, because each member of the population has an equal chance of being included.

Correlation

LOQ 1-

correlation a measure of the extent to which two events vary together, and thus of how well either one predicts the other. The correlation coefficient is the mathematical expression of the relationship, ranging from −1.00 to +1.00, with 0 indicating no relationship.

Describing behavior is a first step toward predicting it. Naturalistic observations and surveys often show us that one trait or behavior relates to another. In such cases, we say the two correlate. A statistical measure (the correlation coefficient) helps us figure how closely two things vary together, and thus how well either one predicts the other. Knowing how much aptitude tests correlate with school success tells us how well the scores predict school success.

A positive correlation (above 0 to +1.00) indicates a direct relationship, meaning that two things increase together or decrease together. Across people, height correlates positively with weight.

A negative correlation (below 0 to −1.00) indicates an inverse relationship: As one thing increases, the other decreases. The number of hours spent watching TV and playing video games each week correlates negatively with grades. Negative correlations can go as low as −1.00. This means that, like children on opposite ends of a teeter-

totter, one set of scores goes down precisely as the other goes up. A coefficient near zero is a weak correlation, indicating little or no relationship.

The point to remember: A correlation coefficient helps us see the world more clearly by revealing the extent to which two things relate.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 1.12

•Indicate whether each of the following statements describes a positive correlation or a negative correlation.

The more husbands viewed Internet pornography, the worse their marital relationships (Muusses et al., 2015).

The less sexual content teens saw on TV, the less likely they were to have sex (Collins et al., 2004).

The longer children were breast-

fed, the greater their later academic achievement (Horwood & Fergusson, 1998). The more income rose among a sample of poor families, the fewer symptoms of mental illness their children experienced (Costello et al., 2003).

ANSWERS: 1. negative, 2. positive, 3. positive, 4. negative

For an animated tutorial on correlations, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Positive and Negative Correlations.

For an animated tutorial on correlations, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Positive and Negative Correlations.

Correlation and Causation

Consider some recent headlines:

“Study finds that increased parental support for college results in lower grades” (Jaschik, 2013)

“People with mental illness more likely to be smokers, study finds” (Belluck, 2013)

“Teenagers who don’t get enough sleep at higher risk for mental health problems” (Rodriguez, 2015)

What shall we make of these correlations? Do they indicate that students would achieve more if their parents supported them less? That stopping smoking would improve mental health? That more sleep would produce better mental health?

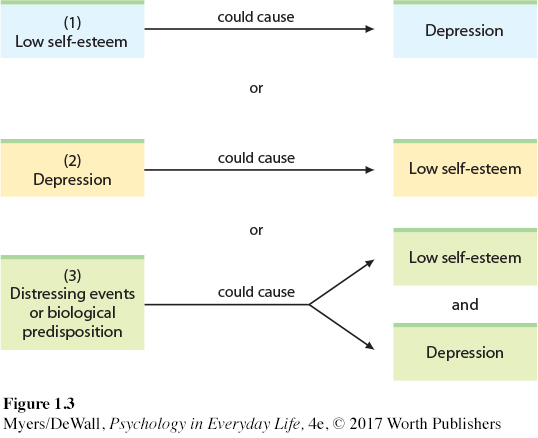

No, because such correlations do not come with built-

But correlations do help us predict. Here’s an example: Self-

How else might we explain the negative correlation between self-

“When scientists communicate with each other, they . . . are cautious about oversimplifying results and speaking beyond the data. But when science is . . . fed to the public, the nuance and uncertainty is often lost.”

Clay Routledge, “What Scientists Know and Need to Share with the Public,” 2015

This point is so important—

The point to remember (turn up the volume here): Correlation indicates the possibility of a cause-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 1.13

•Length of marriage correlates with hair loss in men. Does this mean that marriage causes men to lose their hair (or that balding men make better husbands)?

ANSWER: In this case, as in many others, a third factor can explain the correlation: Golden anniversaries and baldness both accompany aging.

Experimentation

LOQ 1-

experiment a method in which researchers vary one or more factors (independent variables) to observe the effect on some behavior or mental process (the dependent variable). By random assignment of participants, researchers aim to control other factors.

Descriptions, even with big data, don’t prove causation. Correlations don’t prove causation. To isolate cause and effect, psychologists have to simplify the world. In our everyday lives, many things affect our actions and influence our thoughts. Psychologists sort out this complexity by using experiments. With experiments, researchers can focus on the possible effects of one or more factors by

manipulating the factors of interest.

holding constant (“controlling”) other factors.

Let’s consider a few experiments to see how this works.

Random Assignment: Minimizing Differences

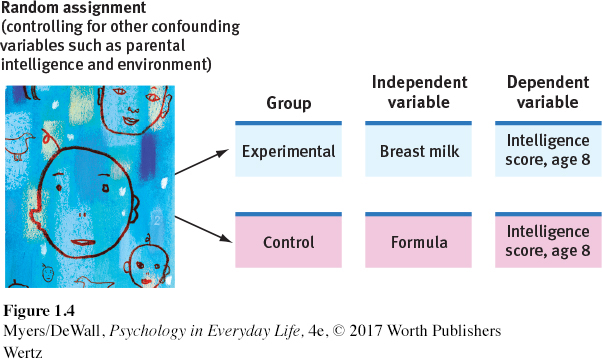

Researchers have compared infants who are breast-

random assignment assigning participants to experimental and control groups by chance, thus minimizing any preexisting differences between the groups.

To find the answer, we would have to isolate the effects of mother’s milk from the effects of other factors, such as mother’s age, education, and intelligence. How might we do that? By experimenting. With parental permission, one British research team directly experimented with breast milk. They randomly assigned 424 hospitalized premature infants either to formula feedings or to breast-

experimental group in an experiment, the group exposed to the treatment, that is, to one version of the independent variable.

an experimental group, in which babies received the treatment (breast milk).

control group in an experiment, the group not exposed to the treatment; the control group serves as a comparison with the experimental group for judging the effect of the treatment.

a contrasting control group without the treatment.

Random assignment (whether by means of a random-

Is breast best? The British experiment found that, at least for premature infants, breast milk is indeed best for developing intelligence. On intelligence tests taken at age 8, those nourished with breast milk scored significantly higher than those who had been formula-

The point to remember: Unlike correlational studies, which uncover naturally occurring relationships, an experiment manipulates (varies) a factor to determine its effect.

The Double-Blind Procedure: Eliminating Bias

In the breast-

Consider: Three days into a cold, many of us start taking vitamin C tablets. If we find our cold symptoms lessening, we may credit the pills. But after a few days, most colds are naturally on their way out. Was the vitamin C cure truly effective? To find out, we could experiment.

placebo [pluh-

And that is precisely what investigators do to judge whether new drug treatments and new methods of psychotherapy are effective (Chapter 14). They use random assignment to form the groups. An experimental group receives the treatment, such as a medication. A control group receives a placebo (an inactive substance—

double-

placebo effect results caused by expectations alone.

Many studies use a double-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 1.14

•What measures do researchers use to prevent the placebo effect from confusing their results?

ANSWER: Research designed to prevent the placebo effect randomly assigns participants to an experimental group (which receives the real treatment) or a control group (which receives a placebo). A double-

Independent and Dependent Variables

Here is an even more potent example: The drug Viagra was approved for use after 21 clinical trials. One trial was an experiment in which researchers randomly assigned 329 men with erectile disorder to either an experimental group (Viagra takers) or a control group (placebo takers). The pills looked identical, and the procedure was double-

independent variable in an experiment, the factor that is manipulated; the variable whose effect is being studied.

confounding variable a factor other than the factor being studied that might influence a study’s results.

Note the distinction between random sampling (discussed earlier in relation to surveys) and random assignment (depicted in FIGURE 1.4). Through random sampling, we may represent a population effectively, because each member of that population has an equal chance of being selected (sampled) for participation in our research. Random assignment ensures accurate representation among the research groups, because each participant has an equal chance of being placed in (assigned to) any of the groups. This helps control outside influences so that we can determine cause and effect.

This simple experiment manipulated just one factor—

dependent variable in an experiment, the factor that is measured; the variable that may change when the independent variable is manipulated.

Experiments examine the effect of one or more independent variables on some behavior or mental process that can be measured. We call this kind of affected behavior the dependent variable because it can vary depending on what takes place during the experiment. Experimenters give both variables precise operational definitions. They specify exactly how the

independent variable (in this study, the precise drug dosage and timing) was manipulated.

dependent variable (in this study, the men’s responses to questions about their sexual performance) was measured.

Operational definitions answer the “What do you mean?” question with a level of precision that enables others to replicate (repeat) the study.

Let’s see how this works with the British breast-

“[We must guard] against not just racial slurs, but . . . against the subtle impulse to call Johnny back for a job interview, but not Jamal.”

Barack Obama, Eulogy for Clementa Pinckney, June 26, 2015

In another experiment, psychologists tested whether landlords’ perceptions of an applicant’s ethnicity would influence the availability of rental housing. The researchers sent identically worded e-

How Would You Know Which Research Design to Use?

Throughout this book, you will read about amazing psychological science discoveries. TABLE 1.2 compares the features of psychology’s main research methods. In later chapters, you will read about other research designs, including twin studies (Chapter 3) and cross-

| Research Method | Basic Purpose | How Conducted | What Is Manipulated | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive | To observe and record behavior | Do case studies, naturalistic observations, or surveys | Nothing | No control of variables; single cases may be misleading. |

| Correlational | To detect naturally occurring relationships; to assess how well one variable predicts another | Collect data on two or more variables; no manipulation | Nothing | Does not specify cause and effect. |

| Experimental | To explore cause and effect | Manipulate one or more factors; use random assignment | The independent variable(s) | Sometimes not possible for practical or ethical reasons. |

In psychological research, no questions are off limits, except untestable ones. Does free will exist? Are people born evil? Is there an afterlife? Psychologists can’t test those questions, but they can test whether free will beliefs, aggressive personalities, and a belief in life after death influence how people think, feel, and act (Dechesne et al., 2003; Shariff et al., 2014; Webster et al., 2014).

Having chosen their question, psychologists then select the most appropriate research design—

To help you build your understanding, your critical thinking, and your scientific literacy skills, we created IMMERSIVE LEARNING research activities in LaunchPad. In these “How Would You Know?” activities, you get to play the role of the researcher, making choices about the best ways to test interesting questions. Some examples: How Would You Know If Having Children Relates to Being Happier?, How Would You Know If a Cup of Coffee Can Warm Up Relationships?, and How Would You Know If People Can Learn to Reduce Anxiety?

Next, psychological scientists decide how to measure the behavior or mental process being studied. For example, researchers could measure aggressive behavior by measuring participants’ willingness to blast a stranger with intense noise.

Researchers want to have confidence in their findings, so they carefully consider confounding variables—

Psychological research is a fun and creative adventure. Researchers design each study, measure target behaviors, interpret results, and learn more about the fascinating world of behavior and mental processes along the way.

To review and test your understanding of experimental methods and concepts, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: The Language of Experiments, and the interactive PsychSim 6: Understanding Psychological Research. For a 9.5-

To review and test your understanding of experimental methods and concepts, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: The Language of Experiments, and the interactive PsychSim 6: Understanding Psychological Research. For a 9.5-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 1.15

•In the rental housing experiment discussed in this section, what was the independent variable? The dependent variable?

ANSWER: The independent variable, which the researchers manipulated, was the implied ethnicity of the applicants’ names. The dependent variable, which researchers measured, was the rate of positive responses from the landlords.

Question 1.16

•Match the term on the left with the description on the right.

|

|

ANSWERS: 1. c, 2. a, 3. b

Question 1.17

•Why, when testing a new drug to control blood pressure, would we learn more about its effectiveness from giving it to half the participants in a group of 1000 than to all 1000 participants?

ANSWER: We learn more about the drug’s effectiveness when we can compare the results of those who took the drug (the experimental group) with the results of those who did not (the control group). If we gave the drug to all 1000 participants, we would have no way of knowing whether the drug is serving as a placebo or is actually medically effective.

Predicting Everyday Behavior

LOQ 1-

When you see or hear about psychology research, do you ever wonder whether people’s behavior in a research laboratory will predict their behavior in real life? Does detecting the blink of a faint red light in a dark room say anything useful about flying a plane at night? Or, suppose an experiment shows that a man aroused by viewing a violent, sexually explicit film will then be more willing to push buttons that he thinks will electrically shock a woman. Does that really say anything about whether violent pornography makes men more likely to abuse women?

Before you answer, consider this. The experimenter intends to simplify reality—

An experiment’s purpose is not to re-

The point to remember: Psychological science focuses less on specific behaviors than on revealing general principles that help explain many behaviors.