Chapter Introduction

1

Psychology:

Evolution of a Science

b

1

A LOT WAS HAPPENING IN 1860. Abraham Lincoln had just been elected president of the United States, the Pony Express had just begun to deliver mail between Missouri and California, and a woman named Anne Kellogg had just given birth to a child who would one day grow up to invent the cornflake. But none of this mattered very much to William James, a bright, taciturn, 18-

Had James become an artist, a biologist, or a physician, we would probably remember nothing about him today. Fortunately for us, he was a deeply confused young man who could speak five languages, and when he became so depressed that he was once again forced to leave medical school, he decided to travel around Europe, where at least he knew how to talk to people. As he talked and listened, he learned about a new science called psychology (from a combination of the Greek psyche [soul] and logos [to study]). He saw that this developing field was taking a modern, scientific approach to age-

2

A LOT HAS HAPPENED SINCE THEN. Abraham Lincoln has become the face on a penny, the Pony Express has been replaced by e-

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. The mind refers to the private inner experience of perceptions, thoughts, memories, and feelings, an ever-

1. What are the bases of perceptions, thoughts, memories, and feelings, or our subjective sense of self?

For thousands of years, philosophers tried to understand how the objective, physical world of the body was related to the subjective, psychological world of the mind. Today, psychologists know that all of our subjective experiences arise from the electrical and chemical activities of our brains. As you will see throughout this book, some of the most exciting developments in psychological research focus on how our perceptions, thoughts, memories, and feelings are related to activity in the brain. Psychologists and neuroscientists are using new technologies to explore this relationship in ways that would have seemed like science fiction only 20 years ago.

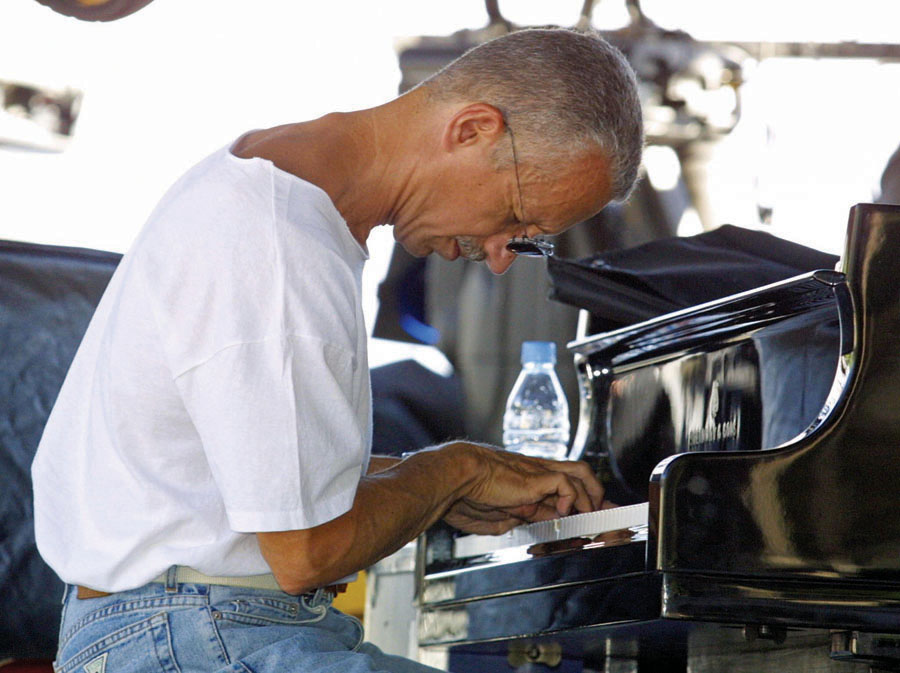

For example, the technique known as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) allows scientists to scan a brain to determine which parts are active when a person reads a word, sees a face, learns a new skill, or remembers a personal experience. In a recent study, the brains of both professional and novice pianists were scanned as they made complex finger movements, like those involved in piano playing. The results showed that professional pianists have less activity than novices in the parts of the brain that guide these finger movements (Krings et al., 2000). This suggests that extensive practice at the piano changes the brains of professional pianists and that the regions controlling finger movements operate more efficiently for them than they do for novices. You’ll learn more about this in the Memory and Learning chapters and see in the coming chapters how studies using fMRI and related techniques are beginning to transform many different areas of psychology.

3

2. How does the mind usually allow us to function effectively in the world?

Scientists sometimes say that form follows function; that is, if we want to understand how something works (e.g., an engine or a thermometer), we need to know what it is working for (e.g., powering vehicles or measuring temperature). As William James often noted, “Thinking is for doing,” and the function of the mind is to help us do those things that sophisticated animals have to do in order to prosper, such as acquire food, shelter, and mates. Psychological processes are said to be adaptive, which means that they promote the welfare and reproduction of organisms that engage in those processes. Perception allows us to recognize our families, see predators before they see us, and avoid stumbling into oncoming traffic. Language allows us to organize our thoughts and communicate them to others, which enables us to form social groups and cooperate. Memory allows us to avoid solving the same problems over again every time we encounter them and to keep in mind what we are doing and why. Emotions allow us to react quickly to events that have life or death significance, and they enable us to form strong social bonds. The list goes on and on.

Given the adaptiveness of psychological processes, it is not surprising that people with deficiencies in these processes often have a pretty tough time. The neurologist Antonio Damasio (1994) described the case of Elliot, a middle-

So what ruined Elliot’s life? The neurologists who tested Elliot were unable to detect any decrease in his cognitive functioning. His intelligence was intact, and his ability to speak, think, and solve logical problems was every bit as sharp as it ever was. But as they probed further, they made a startling discovery: Elliot was no longer able to experience emotions. For example, Elliot didn’t experience any regret or anger when his boss gave him the pink slip and showed him the door, he didn’t experience anxiety when he poured his entire bank account into a foolish business venture, and he didn’t experience any sorrow when his wives packed up and left him. Most of us have wished from time to time that we could be as stoic and unflappable as that; after all, who needs anxiety, sorrow, regret, and anger? The answer is that we all do.

3. Why does the mind occasionally function so ineffectively in the world?

The mind is an amazing machine that can do a great many things quickly. We can drive a car while talking to a passenger while recognizing the street address while remembering the name of the song that just came on the radio. But like all machines, the mind often trades accuracy for speed and versatility. This can produce “bugs” in the system, causing occasional malfunctions in our otherwise efficient mental processing. One of the most fascinating aspects of psychology is that we are all prone to a variety of errors and illusions. Indeed, if thoughts, feelings, and actions were error free, then human behavior would be orderly, predictable, and dull, which it clearly is not. Rather, it is endlessly surprising, and its surprises often derive from our ability to do precisely the wrong thing at the wrong time.

4

Consider a few examples from diaries of people who took part in a study concerning mental errors in everyday life (Reason & Mycielska, 1982, pp. 70–73):

I meant to get my car out, but as I passed the back porch on my way to the garage, I stopped to put on my boots and gardening jacket as if to work in the yard.

I meant to get my car out, but as I passed the back porch on my way to the garage, I stopped to put on my boots and gardening jacket as if to work in the yard. I put some money into a machine to get a stamp. When the stamp appeared, I took it and said, “Thank you.”

I put some money into a machine to get a stamp. When the stamp appeared, I took it and said, “Thank you.” On leaving the room to go to the kitchen, I turned the light off, although several people were there.

On leaving the room to go to the kitchen, I turned the light off, although several people were there.

If these lapses seem amusing, it is because, in fact, they are. But they are also potentially important as clues to human nature. For example, notice that the person who bought a stamp said, “Thank you,” to the machine and not, “How do I find the subway?” In other words, the person did not just do any wrong thing; rather, he did something that would have been perfectly correct in a real social interaction. As each of these examples suggests, people often operate on “autopilot,” or behave automatically, relying on well-

THE REAL WORLD: The Perils of Procrastination

William James understood that the human mind and behavior are fascinating in part because they are not error free. The mind’s mistakes interest us primarily as paths to achieving a better understanding of mental activity and behavior, but they also have practical consequences. Let’s consider a malfunction that can have significant consequences in your own life: procrastination.

At one time or another, most of us have avoided carrying out a task or put it off to a later time. The task may be unpleasant, difficult, or just less entertaining than other things we could be doing at the moment. For college students, procrastination can affect a range of academic activities, such as writing a term paper or preparing for a test. Academic procrastination is not uncommon: Over 70% of college students report that they engage in some form of procrastination (Schouwenburg, 1995). Although it’s fun to hang out with your friends tonight, it’s not so much fun to worry for three days about your impending history exam or try to study at 4:00 a.m. the day of the test. Studying now, or at least a little bit each day, robs procrastination of its power over you.

Some procrastinators defend the practice by claiming that they tend to work best under pressure or by noting that as long as a task gets done, it doesn’t matter all that much if it is completed just before the deadline. Is there any merit to such claims, or are they just feeble excuses for counterproductive behavior?

A study of 60 undergraduate psychology college students provided some intriguing answers (Tice & Baumeister, 1997). At the beginning of the semester, the instructor announced a due date for the term paper and told students that if they could not meet the date, they would receive an extension to a later date. About a month later, students completed a scale that measures tendencies toward procrastination. At that same time, and then again during the last week of class, students recorded health symptoms they had experienced during the past week, the amount of stress they had experienced during that week, and the number of visits they had made to a health care center during the previous month.

Students who scored high on the procrastination scale tended to turn in their papers late. One month into the semester, these procrastinators reported less stress and fewer symptoms of physical illness than did nonprocrastinators. But at the end of the semester, the procrastinators reported more stress and more health symptoms than did the nonprocrastinators, and also reported more visits to the health center. The procrastinators also received lower grades on their papers and on course exams. More recent studies have found that higher levels of procrastination are associated with poorer academic performance (Moon & Illingworth, 2005) and higher levels of psychological distress (Rice, Richardson, & Clark, 2012). Therefore, in addition to making use of the tips provided in the Real World box on increasing study skills, it would seem wise to avoid procrastination in this course and others.

5

James understood that the mind’s mistakes are as instructive as they are intriguing, and modern psychology has found it quite useful to study them. Things that are whole and unbroken hum along nicely and do their jobs while leaving no clue about how they do them. Cars gliding down the expressway might as well be magic carpets as long as they are working properly because we have no idea what kind of magic is moving them along. It is only when automobiles break down that we learn about their engines, water pumps, and other fine pieces and processes that normally work together to produce the ride. Breakdowns and errors are not just about destruction and failure, they are pathways to knowledge. (See the Real World box for an example common to us all: procrastination.) In the same way, understanding lapses, errors, mistakes, and the occasionally puzzling nature of human behavior provides a vantage point for understanding the normal operation of mental life and behavior. The story of Elliot, whose behavior broke down after he had brain surgery, is an example that highlights the role that emotions play in guiding normal judgment and behavior.

Psychology is exciting because it addresses fundamental questions about human experience and behavior, and the three questions we’ve just considered are merely the tip of the iceberg. Think of this book as a guide to exploring the rest of the iceberg. But before we don our parkas and grab our pick axes, we need to understand how the iceberg got here in the first place. To understand psychology in the 21st century, we need to become familiar with the psychology of the past.