The Development of Emotions in Childhood

emotion  emotion is characterized by neural and physiological responses, subjective feelings, cognitions related to those feelings, and the desire to take action

emotion is characterized by neural and physiological responses, subjective feelings, cognitions related to those feelings, and the desire to take action

Most people take the idea of emotion for granted and just equate the term with “feelings.” However, developmentalists have a much more complex view of emotions. They see emotions in terms of several components: (1) neural responses involved in emotion; (2) physiological factors, including heart and breath rate and hormone levels; (3) subjective feelings; (4) the cognitions or perceptions that cause or are associated with the aforementioned neural and physiological responses and subjective feelings; and (5) the desire to take action, including the desire to escape, approach, or change people or things in the environment. In addition, emotions can involve expressive behavior and cognitive interpretations of, or reactions to, the feeling state (Izard, 2010; Saarni et al., 2006).

A simple example illustrates these components in combination: When people experience fear in response to a growling dog, they typically react with heightened physiological arousal, subjective feelings of fearfulness, thoughts about the ways in which the dog might hurt them, and the motivation to get away from the dog. They may also begin calculating their chances of eluding the dog and, finding them slim, imagine the dog to be bigger and more vicious, and themselves more helpless, than previously, thereby increasing their fear.

Although most psychologists share this general view of emotions, they often do not agree on the relative importance of its key components (Lindquist et al., 2013; Mulligan & Scherer, 2012; Tracy & Randles, 2011). For example, some theorists believe that cognition plays a much more important role in the experience of emotion than do other theorists. Moreover, there is considerable debate concerning the degree to which emotions are innate or learned and about when and in what form different emotions emerge during infancy. Before considering the development of specific emotions in childhood, we first need to examine some of the major views that have been proposed regarding the nature and emergence of emotions.

386

Theories on the Nature and Emergence of Emotion

differential (or discrete) emotions theory  a theory about emotions, held by Tomkins, Izard, and others, in which emotions are viewed as innate and discrete from one another from very early in life, and each emotion is believed to be packaged with a specific and distinctive set of bodily and facial reactions

a theory about emotions, held by Tomkins, Izard, and others, in which emotions are viewed as innate and discrete from one another from very early in life, and each emotion is believed to be packaged with a specific and distinctive set of bodily and facial reactions

The debate about the nature and emergence of emotions in children has deep roots. In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, published in 1872, Charles Darwin argued that the facial expressions for certain basic emotional states are innate to the species—and therefore similar across all peoples—and are found even in very young babies. A corresponding view that has been held by some contemporary investigators is differential (or discrete) emotions theory, which has argued that each emotion is innately packaged with a specific set of physiological, bodily, and facial reactions and that distinct emotions can be differentiated very early in life (Ekman & Cordaro, 2011; Izard, 2007, 2011; Tomkins, 1962).

Other researchers maintain that emotions are not distinct from one another at the beginning of life and that environmental factors play an important role in the emergence and expression of emotions. Some argue, for example, that infants experience only excitement and distress in the first weeks of life, and that other emotions emerge at later ages as a function of experience. According to Sroufe (1979, 1995), there are three basic affect systems—joy/pleasure, anger/frustration, and wariness/fear—and these systems undergo developmental change from primitive to more advanced forms during the early years of life. For example, wariness/fear is first expressed as a startle or pain reaction. At a few months of age, infants start to show wariness of novel situations, and a few months later show clear signs of fear in novel situations. In Sroufe’s view, such changes are largely due to infants’ expanding social experiences and their increasing ability to understand them.

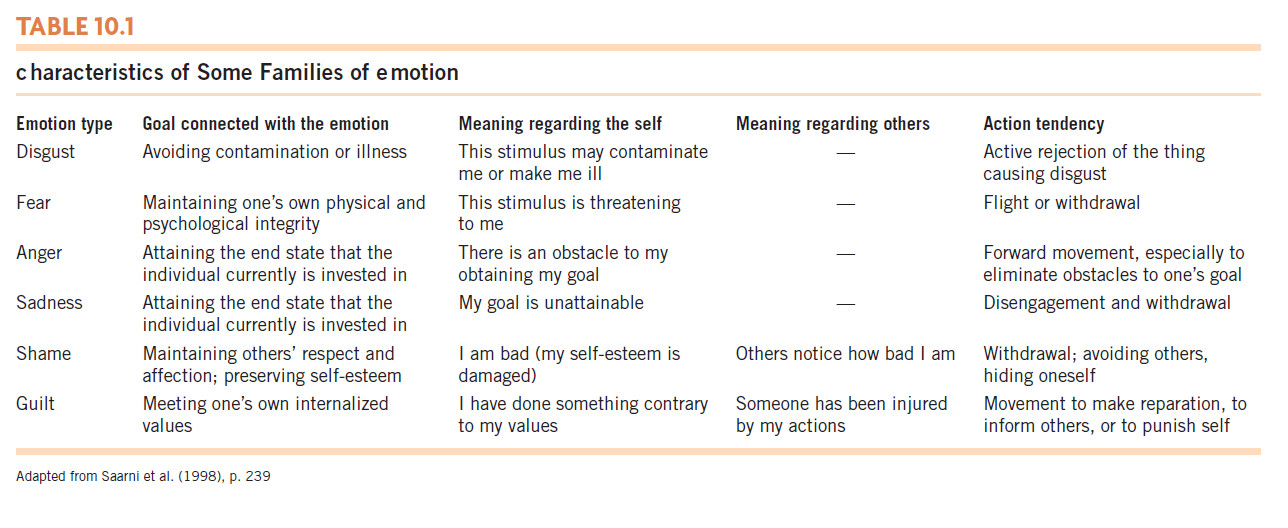

The role of the environment is also emphasized by theorists who take a functionalist approach to understanding emotional development. They propose that the basic function of emotions is to promote action toward achieving a goal in a given context (J. J. Campos et al., 1994; Saarni et al., 2006). The emotion of fear, for instance, often causes one to flee or otherwise avoid a stimulus that represents a threat. This action helps achieve the goal of self-preservation (see Table 10.1 for other examples). Functionalists have also argued that emotional reactions are affected by social goals, the immediate context and the individuals involved in it, as well as others’ interpretations of events and their reactions to them, both in a given context and in the past (Boiger & Mesquita, 2012; Saarni et al., 2006). For example, young children’s experience of emotions such as shame and guilt is related to the values and standards communicated to them by their parents, the manner in which the values and standards are communicated, and the quality of the children’s relationships with their parents.

functionalist approach  a theory of emotion, proposed by Campos and others, that argues that the basic function of emotions is to promote action toward achieving a goal. In this view, emotions are not discrete from one another and vary somewhat based on the social environment.

a theory of emotion, proposed by Campos and others, that argues that the basic function of emotions is to promote action toward achieving a goal. In this view, emotions are not discrete from one another and vary somewhat based on the social environment.

Although these perspectives differ regarding whether distinct emotions emerge early in life, each with its own set of physiological components, they all agree that cognition and experience shape emotional development. However, few theories within these perspectives offer a detailed description of the emotional processing that accounts for the great variation in emotional experience and developmental trajectories across individuals, even among those who share somewhat similar situations or characteristics.

387

An emerging perspective that explicitly deals with how the child’s characteristics and experiences coalesce in emotional processing is dynamic-systems theory (see Chapter 4). From this perspective, novel forms of functioning (emotional or otherwise) arise through the spontaneous coordination of components interacting repeatedly. In these interactions, specific cognitions (including appraisals of events and objects), emotional feelings, and physiological and neural events tend to link together more closely with each repeated occasion, forming coherent “emotional interpretations” that become increasingly coordinated each time they are co-activated (M. D. Lewis, 2005; also see Witherington & Crichton, 2007, and Fogel et al., 1992). A dynamic-systems approach postulates that emotional reactions develop differently for each person, based on an individual’s emotion-related biology and cognitive capacities, his or her experiences, and how these factors tend to coalesce across time in an increasingly coherent and predictable manner. As you will see in the next section, it is not yet clear to what degree infants’ emotions are distinct, emerge early, and can be reliably differentiated. It also is not clear to what degree young children’s basic emotions are innate or develop as a consequence of experience.

The Emergence of Emotion in the Early Years and Childhood

Parents are likely to think that they see many emotions in their infants, including interest and joy, as well as anger, fear, and sadness—even in their 1-month-olds. In fact, however, parents often read into their infant’s emotional reaction whatever emotion would seem appropriate in the immediate situation. For example, if a parent gives an infant a novel toy and the infant reacts negatively, the parent may assume that the infant’s reaction is an expression of fear, when it could just as well be an expression of anger or upset at being overstimulated or at having a current activity disrupted.

To make their own interpretations of infants’ emotions more objective, researchers have devised highly elaborate systems for identifying the emotional meaning of infants’ facial expressions. These systems involve coding dozens of facial cues—whether an infant’s eyebrows are raised or knitted together; whether the eyes are wide open, tightly closed, or narrowed; whether the lips are pursed, softly rounded, or retracted straight back; and so on—and then analyzing the combination in which these cues are present. Even with such detailed analysis, however, it is often hard to determine—beyond positive or negative—exactly what emotions infants are experiencing, and it is particularly difficult to differentiate among the various negative emotions that young infants express.

388

We’ll begin our examination of the emergence of emotions with the easier task—tracing the early development of positive emotions.

Positive Emotions

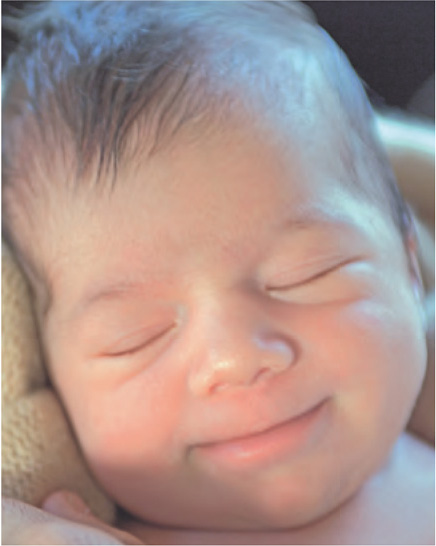

The first clear sign of happiness that infants express is a smile. During the first month, they exhibit fleeting smiles, primarily during the REM phase of sleep; after the first month, they sometimes smile when they are stroked gently. These early smiles may be reflexive and seem to be evoked by some biological state rather than by social interaction (Sroufe & Waters, 1976; Wolff, 1987).

social smiles  smiles that are directed at people. They first emerge as early as 6 to 7 weeks of age.

smiles that are directed at people. They first emerge as early as 6 to 7 weeks of age.

Between the third and eighth week of life, infants begin to smile in reaction to external stimuli, including touching, high-pitched voices, or other stimuli that engage their attention (Sroufe, 1995). More important, by the third month of life, and sometimes as early as 6 or 7 weeks of age, babies begin to exhibit social smiles, that is, smiles directed toward people (B. L. White, 1985). Social smiles frequently occur during interactions with a parent or other familiar people and tend to elicit the adult’s delight, interest, and affection (Camras, Malatesta, & Izard, 1991; Huebner & Izard, 1988). In turn, this response usually inspires more social smiling from the infant. Thus, the infant’s early social smiles likely promote care from parents and other adults and strengthen the infant’s relationships with other people.

The social basis of social smiles is highlighted by the fact that although young infants sometimes smile at interesting objects, humans are much more likely to make them smile. This difference was demonstrated in a study in which 3-month-olds smiled and vocalized much more at people, even strangers, than at puppetlike foam balls that resembled people, were animated, and “talked” to the infant (Ellsworth, Muir, & Hains, 1993).

When infants are at least 2 months of age, they also show happiness in both social and nonsocial contexts in which they can control a particular event. In one study that demonstrated this, researchers divided infants into two groups and attached a string to an arm of each infant. Observing the infants individually, they arranged for infants in one group to hear music whenever they pulled the string and for infants in the other group to hear music at random intervals. The infants who “caused” the music to play by pulling on the string showed more interest and smiling when the music came on than did the infants whose string-pulling had no connection to the music’s being played (M. Lewis, Alessandri, & Sullivan, 1990). This pleasure in controlling events is evident in infants’ delight when they can consistently make a noise by shaking their rattle or banging a toy on the floor.

At about 7 months of age, infants start to smile primarily at familiar people, rather than at people in general. (In fact, as you will see, unfamiliar people often elicit distress at this age.) These selective smiles tend to delight parents and motivate them to continue interacting with the infant. In turn, infants of this age often respond to parents’ playfulness and smiles with excitement and joy, which also prolongs their positive social interactions (Weinberg & Tronick, 1994). Such exchanges of positive affect, especially when they occur with parents but not with strangers, make parents feel special to the infant and strengthen the bond between them.

389

Children’s expression of positive emotion increases across the first year of life (Rothbart & Bates, 2006), perhaps because they are able to understand and respond to more interesting and positive events and stimuli. After about 3 or 4 months of age, infants laugh as well as smile during a variety of activities. For example, they are likely to laugh when a parent tickles them or blows on their tummy, bounces them on a knee or swings them around in the air, or shares a favorite activity such as bathing with them. By late in the first year of life, children’s cognitive development allows them to take pleasure from unexpected or discrepant events such as Mom’s making a funny noise or wearing a goofy hat (Kagan, Kearsley, & Zelazo, 1978).

During the second year of life, children start to clown around themselves and are delighted when they can make other people laugh—as in the case of this 18-month-old who looks at his mother and, fully clothed, sits on his potty:

Child: Poo (grunts heavily). Poo! (grunts). Poo! (gets up, looks at Mother, picks up empty potty, and waves it at Mother, laughing)

(Dunn, 1988, p. 154)

Incidents like this are common in the second year of life and demonstrate infants’ desire to share positive emotion and activities with parents.

Across the preschool years and elementary school years, children’s expression of positive emotion in social interactions, especially intense positive emotion, has been found to decline (Sallquist et al., 2009, 2010). This pattern might be due to children’s learning to modulate their expression of positive emotion, especially in contexts in which it might be inappropriate or disruptive to working on tasks (Kochanska et al., 2007).

Negative Emotions

The first negative emotion that is discernible in newborn infants is generalized distress, which can be evoked by a variety of experiences ranging from hunger and pain to overstimulation. Often expressed with piercing cries and a face screwed up in a tight grimace, this type of distress is unmistakable.

The emergence and development of other negative emotions in infancy are, as noted earlier, more difficult to pin down. A number of studies suggest that negative emotion in young infants continues to be expressed as undifferentiated distress (Oster, Hegley, & Nagel, 1992) and that anger and distress/pain are especially likely to be undifferentiated in most contexts (Camras, 1992; Camras & Shutter, 2010). Dynamic-systems theorists have argued that differentiating among infants’ expression of emotions is difficult partly because their expressions of emotion are affected by nonemotional factors such as the position of their head, their respiration, and where they are looking (which affects the eyebrow and areas around the eye), as well as by their immediate experience of emotion and interpretation of the context (Camras, 2011). It is also likely that infants’ expressions of emotion often reflect a mix of emotions, which makes it additionally difficult to know what infants are feeling (M. Lewis, 2011).

The interpretation of negative emotions is complicated by the fact that infants sometimes display negative emotions that seem incongruent with the situation they are experiencing (Bennett, Bendersky, & Lewis, 2002; Camras, 1992; Hiatt, Campos, & Emde, 1979). In the string-pulling study cited earlier, for example, the infants who could “control” the music by pulling the string attached to their arms fussed and sometimes expressed anger when their pulling of the string no longer produced music. Other times, however, these infants showed fear when pulling the string no longer produced music (M. Lewis et al., 1990). Incongruities such as these highlight the difficulty of knowing for certain what emotion an infant may be experiencing in certain situations.

390

In some contexts involving relatively intense emotion, however, investigators have been able to differentiate among certain negative emotions in fairly young infants. By 2 months of age, for example, facial expressions that appear to represent anger and sadness have been reliably differentiated from each other and from distress/pain in situations such as getting an injection during a medical procedure (Izard, Hembree, & Huebner, 1987). The correspondence between the context and infants’ emotional expressions seems to become more consistent from 5 to 12 months of age. For example, in research in which experimenters prevented infants from moving their arms, the infants’ expressions indicative of anger increased with age, whereas their expressions of interest and surprise decreased (Bennett, Bendersky, & Lewis, 2005).

Fear and distress Although there is little firm evidence of distinct fear reactions in infants during the first months of life (Witherington, Campos, & Hertenstein, 2001), by 4 months of age, infants do seem wary of unfamiliar objects and events (Sroufe, 1995). Then, at around the age of 6 or 7 months, initial signs of fear begin to appear (Camras et al., 1991), most notably the fear of strangers in many circumstances. In part, this shift likely reflects infants’ recognition that unfamiliar people do not provide the comfort and pleasure that familiar people do.

Consider the following contrast: at the age of 10 weeks, as Janine was whimpering in her crib, a stranger came over and smiled and talked to her. Janine stopped fussing and smiled at the stranger. At the age of 8 months, Janine is playing on her mother’s knee when her mother has to put her down and leave the room to answer the door. A moment later the visitor, a stranger, enters the room without Janine’s mother.

When the visitor enters, Janine cries. The visitor tries to comfort Janine by picking her up and talking softly to her, but she cries still more frantically until her mother returns and holds her. Then Janine calms down and smiles when mother lifts her high in the air in play.

(Bronson, 1972)

In general, the fear of strangers intensifies and lasts until about age 2. However, it should be noted that the fear of strangers is quite variable (Sroufe, 1995), depending on both the infant’s temperament (i.e., how fearful the infant is in general) and the specific context, such as whether a parent is present and the manner in which the stranger approaches (e.g., abruptly and excitedly or slowly and calmly).

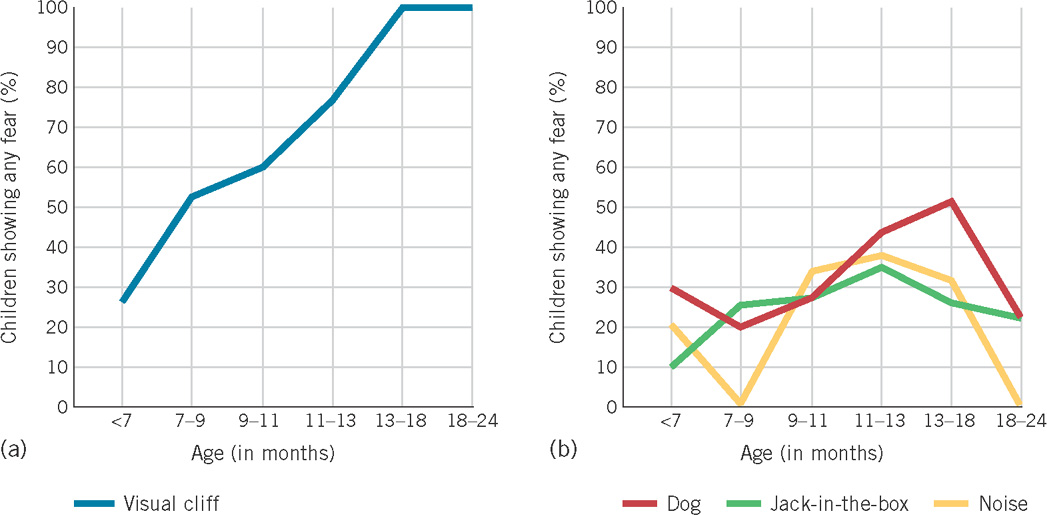

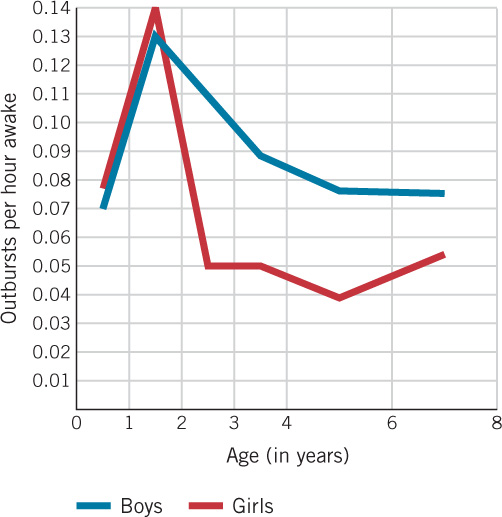

Other fears are also evident at around the age of 7 months, including fear of novel toys, loud noises, and sudden movements by people or objects, all of which tend to increase until about 12 to 16 months of age (see Figure 10.1; Braungart-Rieker, Hill-Soderlund, & Karrass, 2010; Kagan et al., 1978; Scarr & Salapatek, 1970). The emergence of such fears is clearly adaptive. Because babies often do not have the ability to escape from potentially dangerous situations on their own, they must rely on their parents to protect them, and expressions of fear and distress are powerful tools for bringing help and support when they are needed. Individual differences in the decline in these kinds of fears seem to be related to the quality of children’s relationships with their mothers and how effectively their mothers deal with their children’s expressions of fear (K. A. Buss & Kiel, 2011; Kochanska, 2001).

391

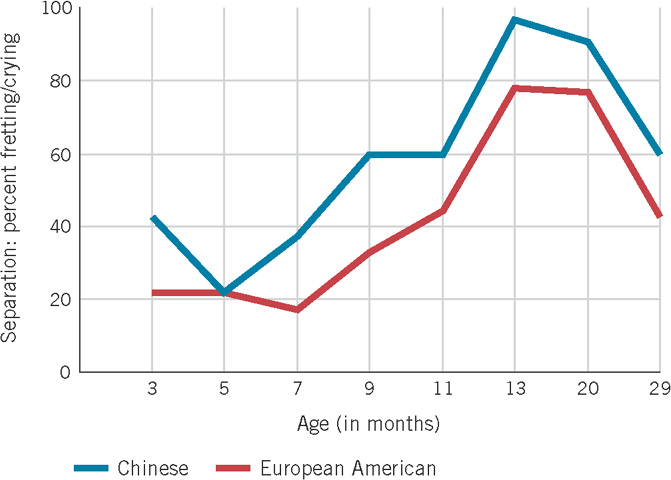

An especially salient and important type of fear or distress that emerges at about 8 months of age is separation anxiety—distress due to separation from the parent who is the child’s primary caregiver. When infants experience separation anxiety, they typically whine, cry, or otherwise express fear and upset. However, the degree to which children exhibit such distress varies with the context. For example, infants show much less distress when they crawl or walk away from a parent than when the parent does the departing (Rheingold & Eckerman, 1970). Separation anxiety tends to increase from 8 to 13 or 15 months of age, and then begins to decline (Kagan, 1976). This pattern of separation anxiety occurs across many cultures, displayed by infants reared in environments as disparate as the U.S. middle class, Israeli kibbutzim (communal farming communities), and !Kung San hunting-and-gathering groups in the Kalahari Desert in Africa (Kagan, 1976). (Figure 10.2 shows this pattern in Chinese and European American children.)

separation anxiety  feelings of distress that children, especially infants and toddlers, experience when they are separated, or expect to be separated, from individuals to whom they are emotionally attached

feelings of distress that children, especially infants and toddlers, experience when they are separated, or expect to be separated, from individuals to whom they are emotionally attached

Anger and sadness

It is likely that anger is distinct from other negative emotions by 4 to 8 months of age (Camras et al., 1991; M. W. Sullivan & Lewis, 2003). By their 1st birthday, infants clearly and frequently express anger, often toward other people (Radke-Yarrow & Kochanska, 1990), and their expression of anger typically increases until 16 months of age, although there is considerable variation in this pattern across infants (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2010). Over the course of their second year, as children become better able to control their environments, they are increasingly likely to be upset when control is taken away from them or when they are otherwise frustrated (see Figure 10.3) (Goodenough, 1931).

392

Infants often exhibit sadness in the same types of situations in which they show anger, such as after a painful event and when they cannot control outcomes in their environment, although displays of sadness appear to be somewhat less frequent than displays of anger or distress (Izard et al., 1987, 1995; M. Lewis et al., 1990; Shiller, Izard, & Hembree, 1986). In addition, when older infants or young children are separated from their parents for extended periods and are not given sensitive care during this period, they often show intense and prolonged displays of sadness (Bowlby, 1973; J. Robertson & Robertson, 1971).

Except in the case of children who have problematic relationships, the expression of negative emotion, and perhaps the experiencing of it as well, generally decline after the second year of life (Kochanska, 2001). Toddlers are quicker to respond with physical expressions of anger at 18 to 24 months of age than they are at 36 months or older (P. M. Cole et al., 2011); and from age 3 to 6 years, children show less negative emotion on structured laboratory tasks designed to elicit it (Durbin, 2010). The general decline in negative emotionality is likely due to children’s increasing ability to express themselves with language (Kopp, 1992), as well as to the increasing ability for the average child to regulate the expression of their negative feelings.

The Self-Conscious Emotions: Embarrassment, Pride, Guilt, and Shame

self-conscious emotions  emotions such as guilt, shame, embarrassment, and pride that relate to our sense of self and our consciousness of others’ reactions to us

emotions such as guilt, shame, embarrassment, and pride that relate to our sense of self and our consciousness of others’ reactions to us

During the second year of life, children begin to show a range of new emotions: embarrassment, pride, guilt, and shame (Stipek, Gralinski, & Kopp, 1990; R. A. Thompson, 2006; Zahn-Waxler & Robinson, 1995). These emotions often are called self-conscious emotions because they relate to our sense of self and our consciousness of others’ reactions to us. Some investigators such as Michael Lewis believe that these emotions emerge in the second year because that is when children gain the understanding that they themselves are entities distinct from other people and begin to develop a sense of self (M. Lewis, 1998). Such a view implies an abrupt, qualitative change in children’s abilities to experience these emotions and suggests discontinuity in emotional development due to the emergence of an underlying cognitive awareness (M. Lewis, 1998; Mascolo, Fischer, & Li, 2003). The emergence of self-conscious emotions is also fostered by children’s growing sense of what adults and society expect of them and their acceptance of these external standards (Lagattuta & Thompson, 2007; M. Lewis, Alessandri, & Sullivan, 1992; Mascolo et al., 2003).

At about 15 to 24 months of age, some children start to show embarrassment when they are made the center of attention. Asked to show off an ability or a new piece of clothing, for example, they lower their eyes, hang their head, blush, or hide their face in their hands (M. Lewis, 1995).

The first signs of pride are evident in children’s smiling glances at others when they have successfully met a challenge or achieved something new, like taking their first step. By 3 years of age, children’s pride is increasingly tied to the level of their performance. Children express more pride, for example, when they succeed on difficult tasks than they do when they succeed on easy ones (M. Lewis et al., 1992).

393

The two other self-conscious emotions, guilt and shame, are sometimes mistakenly thought of as roughly equivalent, but they are actually quite distinct. Guilt is associated with empathy for others and involves feelings of remorse and regret about one’s behavior, as well as the desire to undo the consequences of that behavior (M. L. Hoffman, 2000). In contrast, shame does not seem to be related to concern about others. When children feel shame, their focus is on themselves: they feel that they are exposed, and they often feel like hiding (N. Eisenberg, 2000; Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007).

Shame and guilt can be distinguished fairly early, as documented by a study in which researchers arranged for 2-year-olds to play with a doll belonging to an adult (the experimenter). The doll had been rigged so that one leg would fall off during play, while the adult was out of the room. When the “accident” occurred, some toddlers displayed a pattern of behavior that seemed to reflect shame—that is, they avoided the adult when she returned to the room and delayed telling her about the mishap. Other children showed a pattern of behavior that seemed to reflect guilt—that is, they repaired the doll quickly, told the adult about the mishap shortly after she returned to the room, and showed relatively little avoidance of her (Barrett, Zahn-Waxler, & Cole, 1993). In general, the degree of association of guilt feelings with bad or hurtful behavior increases in the second to third year (Aksan & Kochanska, 2005), and the individual differences in children’s guilt observed at 22 months of age remain relatively stable across the early preschool years (Kochanska, Gross et al., 2002).

In everyday life as well, the same situation often elicits shame in some individuals and guilt in others. Which emotion children experience partly depends on parental practices. Studies of North American children have found that they are more likely to experience guilt than shame if, when they have done something wrong, their parents emphasize the “badness” of the behavior (“You did a bad thing”) rather than of the child (“You’re a bad boy”). In addition, children are more likely to feel guilt rather than shame if their parents help them understand the consequences their actions have for others, teach them the need to repair the harm they have done, avoid publicly humiliating them, and communicate respect and love for their children even when disciplining them (M. L. Hoffman, 2000; Tangney & Dearing, 2002).

The situations likely to induce self-conscious emotions in children vary across cultures, as does the frequency with which specific self-conscious emotions are likely to be experienced (P. M. Cole, Tamang, & Shrestha, 2006). For instance, among traditional Zuni Indians, standing out from others is discouraged. As a result, Zuni children who achieve an individual success, such as doing better than peers on a project, are likely to feel embarrassment or shame (Benedict, 1934). Similarly, the Japanese tend to avoid bestowing praise on the individual because they believe that it encourages a focus on the self rather than on the needs of the larger social group (M. Lewis, 1992). Correspondingly, Japanese children, in comparison with U.S. children, are less likely to report experiencing pride as a consequence of personal success (Furukawa et al., 2012).

Moreover, in many Asian or Southeast Asian cultures that emphasize the welfare of the group rather than the individual, not living up to social or familial obligations is likely to evoke shame or guilt (Mascolo et al., 2003), and children in these cultures report experiencing guilt and shame more than do children in the United States (Furukawa et al., 2012). In such cultures, parents’ efforts to elicit shame from their young children are often direct and disparaging (e.g., “You made your mother lose face,” “I’ve never seen any 3-year-old who behaves like you”) (Fung & Chen, 2001). This kind of explicit belittling appears to have a more positive effect on children in these Asian cultures than it does on children in Western cultures.

394

Normal Emotional Development in Childhood

The causes of emotions continue to change in childhood. For example, the basis of children’s self-esteem or self-evaluation changes with cognitive development and experience (see Chapter 11), and the events that make children feel happiness and pride tend to change accordingly. From early to middle childhood, for instance, acceptance by peers and achieving goals become increasingly important, and successes in these areas become key sources of happiness and pride. What makes children smile and laugh also changes with age. As their language skills develop along with their understanding of people and events, children in the preschool years begin to find verbal jokes funny (Dunn, 1988).

Similar examples can be seen in regard to children’s negative emotions. For instance, as their cognitive ability to represent imaginary phenomena develops in the preschool years, children often start to fear imaginary creatures such as ghosts or monsters. Such fears are uncommon in elementary school children (Silverman, La Greca, & Wasserstein, 1995), probably because children of this age have a better understanding of reality than do younger children. Instead, school-aged children’s anxieties and fears are generally related to important, real-life issues (albeit sometimes exaggerated), such as challenges at school (tests and grades, being called on in class, and pleasing teachers), health (their parents’ and their own), and personal harm (being robbed, mugged, or shot). The causes of anger also change as children develop a better understanding of others’ intentions and motives. For example, in the early preschool years, a child is likely to feel anger when harmed by a peer whether or not the harm was intentional. In contrast, young school-aged children are less likely to be angered if they believe that harm done to them was unintentional or that the motive for some harmful action was benign rather than malicious (Coie & Dodge, 1998; Dodge, Murphy, & Buchsbaum, 1984).

The frequency with which specific emotions are experienced also may change in childhood and adolescence. There is some evidence, for example, that over the course of the preschool and early school years, children generally become less emotionally intense and negative (Guerin & Gottfried, 1994; B. C. Murphy et al., 1999; Sallquist et al., 2009). There is also some support for the common assumption that negative emotion increases after middle childhood. Typically, early to middle adolescence is marked by an increase in the frequency or intensity of negative emotions and a decrease in positive emotion. For most youths, the increase is mild (Larson & Lampman-Petraitis, 1989; Larson et al., 2002; Weinstein et al., 2007), but for a minority, it is quite sharp, often in their relations with their parents (Collins & Steinberg, 2006; Laursen, Coy, & Collins, 1998; see also Chapter 12). This negative shift in average emotions generally appears to end by grade 10, and older adolescents also experience less emotional lability (i.e., day-to-day change) than do young adolescents (Larson et al., 2002; Weinstein et al., 2007).

395

Of course, children’s emotional states are highly influenced by the world around them, with negative emotion being intensified by stressful conditions. As might be expected, children and adolescents directly exposed to war or terrorism tend to experience unusually high levels of fear, anxiety, and depression (N. Eisenberg & Silver, 2011; P. T. Joshi & O’Donnell, 2003; Weems et al., 2010). Exposure to lesser stressors, such as conflict between parents in the home, or a single mother’s entrance into a new romantic relationship or co-habitation arrangement, also appears to increase children’s experience of negative emotion such as fear (Bachman, Coley, & Carrano, 2011; Davies, Cicchetti, & Martin, 2012; Rhoades, 2008).

Depression

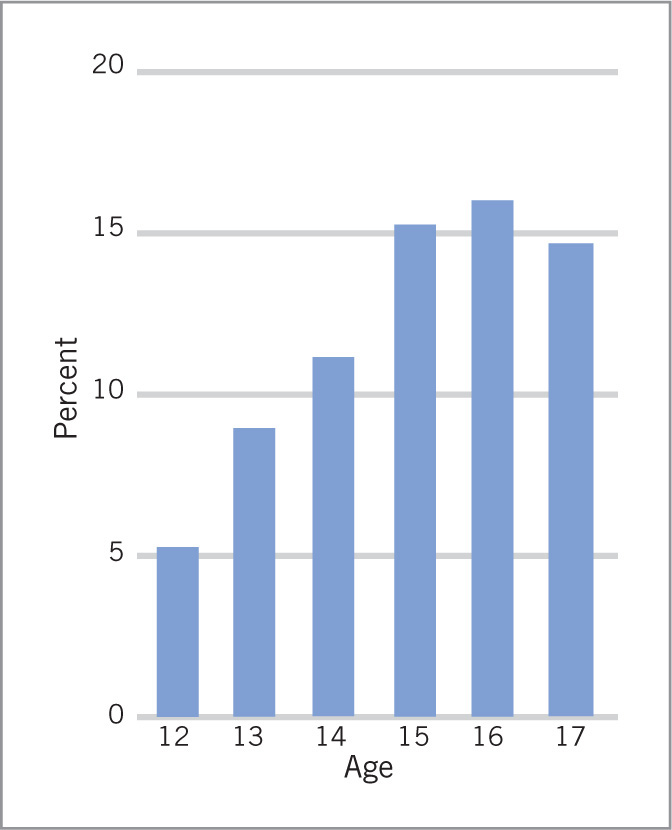

Major bouts of depression are much more common in adolescence than in childhood, although a small percentage of preschoolers exhibit depressive symptoms that predict problems with depression in the school years (Luby, 2010). Prior to adolescence, a child’s chance of experiencing a period of major depression is less than 3% (E. J. Costello, Erkanli, & Angold, 2006), but between ages 12 and 17, this figure increases to more than 4% for boys and more than 12% for girls (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2012).

Major, or clinical, depression is characterized by some combination of at least five of the following symptoms, occurring nearly every day for at least two weeks: depressed mood most of the time; marked diminished interest or pleasure in almost all activities; significant weight loss; insomnia or excessive sleeping; motor agitation; fatigue or loss of energy; feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt; diminished ability to think or concentrate; recurrent thoughts of death (Hammen & Rudolph, 2003). Besides these specific diagnostic criteria, social withdrawal and bodily complaints are common in depressed youth, as is anxiety (C. M. Turner & Barrett, 2003).

In addition to the adolescents who experience major depression, more than 10% of U.S. youths experience depressive symptoms that are not severe and persistent enough to be classified as clinical (Hammen & Rudolph, 2003). As discussed in Box 10.1, this rate is even higher for girls.

Some investigators have found that adolescents from a lower socioeconomic level are especially prone to major depression (Hammen & Rudolph, 2003). In terms of nonclinical symptoms of depression, however, adolescents’ self-reports do not reflect such socioeconomic differences, although they do suggest some ethnic differences, with Hispanic children reporting more symptoms of depression than do European American or African American youth (Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002).

There are many possible causes of depression. One is heredity: major depression often runs in families. Children whose mothers are depressed tend to exhibit a pattern of activation in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala that is associated with greater reactivity to the environment, negative emotionality, and withdrawal; they also may have elevated hormone-based stress reactivity (Cicchetti & Toth, 2006; Joormann et al., 2011). These biological correlates likely are partly due to a genetic vulnerability, but they also could be exacerbated by problems in parenting that often accompany maternal depression (Cicchetti & Toth, 2006), including insensitivity and disengagement (Belsky, Schlomer, & Ellis, 2012; S. B. Campbell et al., 2007; Garber & Cole, 2010; Lovejoy et al., 2000).

396

Box 10.1: individual differences

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN ADOLESCENT DEPRESSION

One of the most striking features of adolescent depression is the gender-related differences in its occurrence (D. M. Costello et al., 2008; Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). By age 12, the rate of depression among U.S. girls is slightly higher than that for boys, and by age 17, girls are roughly three times more likely to be depressed (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2012; Garber, Keiley, & Martin, 2002; Hankin & Abramson, 1999). Especially alarming is a tripling in the rate of major depression for U.S. girls between ages 12 and 15 (see figure; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2012). Similar gender differences in the patterns of adolescent depression have been found in numerous countries (Galambos, Leadbeater, & Barker, 2004; Hankin et al., 1998; Wichstrom, 1999).

rumination  a perseverative focus on one’s own negative emotions and on their causes and consequences, without engaging in efforts to improve one’s situation

a perseverative focus on one’s own negative emotions and on their causes and consequences, without engaging in efforts to improve one’s situation

Why are adolescent girls more likely than boys to experience depression? The biological changes of puberty tend to be more difficult for girls and may contribute to girls’ vulnerability (Hilt & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2009). It also seems likely that a key factor is the greater socioemotional stress that adolescence represents for girls (Petersen, Sarigiani, & Kennedy, 1991), at least in certain cultures. Important stressors may include concerns about one’s body and appearance (Hankin, Mermelstein, & Roesch, 2007). As discussed in Chapter 15, adolescent girls in the United States report greater dissatisfaction with their bodies than boys report with theirs. This dissatisfaction, fueled by a cultural obsession with an “ideal” body type attainable only by a few, seems to contribute substantially to low self-esteem and depression in adolescent girls (Compian, Gowen, & Hayward, 2004; Hankin & Abramson, 1999; Harter, 2006; Wichstrom, 1999). Another stressor for girls can be the social consequences of early puberty, which represent a clear risk for depression (Negriff & Susman, 2011). Early maturity, for example, may lead young adolescent girls to become involved with older adolescent boys, who may pressure them to engage in sexual activity, drinking, or delinquency. Many younger girls often are not cognitively and socially mature enough to cope with these pressures (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 1996; Ge et al., 2003). In contrast, for boys, early puberty has been less consistently related to internalizing problems such as depression. However, recent evidence suggests that boys who enter puberty early and move through it quickly are, in fact, at risk for depression (Ge et al., 2003; Mendle et al., 2010), in part because of a decline in the quality of their relationships with peers (Mendle et al., 2012). For both sexes, early puberty is especially likely to be associated with depressive symptoms if it is accompanied by low popularity (Teunissen et al., 2011). For boys, starting puberty later than one’s peers is a predictor of depression as well (Negriff & Susman, 2011).

co-rumination  extensively discussing and self-disclosing emotional problems with another person

extensively discussing and self-disclosing emotional problems with another person

Also appearing to contribute to the higher rates of depression for adolescent girls is the fact that they, more than their male peers, are prone to repeatedly focus on causes, consequences, and symptoms of their negative emotion (“I’m so fat” or “I’m so tired”) and on the meaning of their distress (“What’s wrong with my life?”) without engaging in efforts to remedy their situation (Hankin, Stone, & Wright, 2010; Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999). Such thinking, called rumination, seems to increase the chances of becoming depressed, and some researchers have found this relation to be stronger for girls than for boys (Abela et al., 2012; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2007). Moreover, co-rumination—that is, extensively discussing and self-disclosing emotional problems with another person (usually a peer)—is more common for girls and seems to further account for the gender difference in depression (A. J. Rose, 2002). However, co-rumination predicts greater severity of depression and anxiety in boys as well as girls (Hankin et al., 2010; Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2012; L. B. Stone et al., 2011).

Other family factors likely also contribute to depression in youth. In particular, whether or not the mother is depressed, children’s symptoms of depression are frequently associated with low levels of family engagement, support, and acceptance and with high levels of negativity (Auerbach et al., 2011; Kiff et al., 2011; O. S. Schwartz et al., 2012). Chronic stress and conflict in the family also predict depression in youths (Brennan et al., 2002; Karevold et al., 2009; H. K. Kim, Capaldi, & Stoolmiller, 2003).

397

In addition, some investigators emphasize the role that maladaptive belief systems play in the onset and maintenance of depression (Beck, 1983; Hammen & Rudolph, 2003). They argue, for example, that depressed individuals tend to see themselves and others in an excessively negative way and, thus, feel incompetent, flawed, and worthless, and view the world as cruel and unfair (Bohon et al., 2008; K. B. Hoffman et al., 2000; Rudolph & Clark, 2001). They may also feel that they cannot change things for the better because they believe that negative events are beyond their control, and they often do not take credit for their accomplishments (Garber et al., 2002; Gregory et al., 2007; Seligman, 1975). Finally, as noted in Box 10.1, depressed youths also tend to ruminate about the potential causes and negative consequences of their symptoms (Schniering & Rapee, 2004); this rumination can intensify their negative feelings without leading to productive problem solving and solutions (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008; Silk et al., 2003). All these ideas about the causes of depression have received some support from research (Abela et al., 2011; Hammen & Rudolph, 2003).

Other investigators argue that youths get depressed because they lack the skills needed for appropriate emotion regulation and positive social interactions (e.g., P. M. Cole, Luby, & Sullivan, 2008; Kovacs et al., 2008). Consistent with this view, children and adolescents who experience depression frequently are low in regulation and exhibit behavioral problems such as aggression, stealing, delinquency, and substance abuse (see Chapter 14; Diamantopoulou et al., 2011; Wiesner & Kim, 2006; Yap et al., 2011). This pattern may contribute to the difficulties depressed youths often tend to have in their relationships with peers (Rudolph, Ladd, & Dinella, 2007; Teunissen et al., 2011).

It has also been proposed that peer victimization and rejection contribute to depression (Hawker & Boulton, 2000; Witvliet et al., 2010), an idea that seems supported by the finding that a sense of connection with peers and school is associated with less depression (Auerbach et al., 2011; D. M. Costello et al., 2008). However, evidence from a recent study that followed children from 4th grade to 6th grade suggests that children’s depression contributes to peer victimization, which in turn predicts low acceptance by peers, and that problems with peers did not cause depression (Kochel et al., 2012).

In many cases, depression is likely due to a combination of personal vulnerability and external stressful factors (Lewinsohn, Joiner, & Rohde, 2001). In a study of youths making the transition to middle school, for instance, those who felt that they had little control over their success in school and who demonstrated little investment in school were especially likely to show an increase in depressive symptoms if they also experienced the transition as stressful (Rudolph et al., 2001). Other research found that girls who were low in the regulation of sadness were prone to depressive symptoms in preadolescence if their parents were not especially caring and supportive (Feng et al. 2009). In addition, the combination of family difficulties (e.g., separation from parents) in early childhood and high levels of interpersonal stress later on may increase youths’ vulnerability to depression (Rudolph & Flynn, 2007), perhaps because early stress can affect the child’s ability to adapt physiologically years later (Gunnar & Vazquez, 2006).

The most common treatment for depression in youth is drug therapy, but recent concerns have been raised about the possibility that antidepressants may increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior for some adolescents (Calati et al., 2011). An alternative therapy that has been shown to reduce adolescents’ depressive symptoms to some degree involves programs designed to promote optimistic thinking and teach positive approaches to solving personal problems (Gillham et al., 1995; Jaycox et al., 1994; S. H. Spence, Sheffield, & Donovan, 2003).

398

review:

Emotions are fundamental for much of human functioning and undergo change in the early months and years of life. Smiles emerge early but do not become social until the 2nd to 3rd month of life, and what makes children smile and laugh changes with age and cognitive development. Distress in newborns involves hunger and various other discomforts; by 6 to 7 months of age, it is often caused by a stranger’s approach; by approximately 8 months of age, it is likely to be triggered by a separation from parents. Separation distress develops in similar ways in various cultures.

It is hard to know exactly when anger emerges because distress/pain and anger are difficult to differentiate early in life. Children may experience anger by the second month of life in response to loss of control. In the first months, it is similarly difficult to differentiate fear from distress, but fear likely has emerged by 6 or 7 months of age, when some children appear to display fear of strangers. Young children also exhibit sadness, especially when they are separated from loved ones for extended periods.

The self-conscious emotions—embarrassment, pride, shame, and guilt—emerge somewhat later than do most emotions, probably in the second year of life. Their emergence is tied in part to the development of a rudimentary sense of self and to an appreciation of others’ reactions to the self. Situations that evoke these emotions vary across cultures.

Emotions continue to change in their occurrence and causes in childhood and adolescence. Depression increases markedly in adolescence, especially for girls. Age-related cognitive, biological, and experiential factors likely account for these changes.