Writing a Draft: Invention, Research, Planning, and Composing

The activities in this section will help you choose a subject to profile and develop your perspective on the subject. Do the activities in any order that makes sense to you (and your instructor), and return to them as needed as you revise.

Although some of the activities will take only a few minutes each to complete, the essential field research—

Choose a subject to profile.

To create an informative and engaging profile, your subject—

a subject that sparks your interest or curiosity;

a subject your readers will find interesting and informative;

a subject you can gain access to and observe in detail in the time allowed;

a subject about which (or with whom) you can conduct in-

depth interviews.

Note: Whenever you write a profile, consider carefully the ethics involved in such research: You will want to be careful to treat participants fairly and with respect in the way you both approach and depict them. Discuss the ethical implications of your research with your instructor, and think carefully about the goals of your research and the effect it will have on others. You may also need to obtain permission from your school’s ethics review board.

Make a list of appropriate subjects. Review the “Consider possible topics” in “The Hunger Games” (Ranson), “The Long Good-bye” (Coyne), and “A Gringo in the Lettuce Fields” (Thompson).” and consult your school’s Web site to find intriguing places, activities, or people on campus. The following ideas may suggest additional possibilities to consider:

A place where people come together because they are of the same age, gender, sexual orientation, or ethnic group (for example, a foreign language–speaking dorm or fraternity or sorority), or a place where people of different ages, genders, sexual orientations, or ethnic groups have formed a community (for example, a Sunday morning pickup basketball game in the park, LGBT club, or barbershop)

A place where people are trained for a certain kind of work (for example, a police academy, cosmetology program, truck driving school, or boxing ring)

A group of people working together for a particular purpose (for example, students and their teacher preparing for the academic decathlon, employees working together to produce something, law students and their professor working to help prisoners on death row, or scientists collaborating on a research project)

TEST YOUR CHOICE

Considering Your Purpose and Audience

After you have made a tentative choice, ask yourself the following questions:

Do I feel curious about the subject?

Am I confident that I will be able to make the subject interesting for my readers?

Do I believe that I can research this subject sufficiently in the time I have?

Then get together with two or three other students:

Presenters. Take turns identifying your subjects. Explain your interest in the subject, and speculate about why you think it will interest readers.

Listeners. Briefly tell each presenter what you already know about his or her subject, if anything, and what might make it interesting to readers. (To learn more about conducting observations and interviews, see Chapter 21, “Conducting Field Research.”)

Conduct your field research.

To write an effective profile, conduct field research—interviews and observations—

WAYS IN

HOW CAN I MANAGE MY TIME?

Try this BACKWARD PLANNING strategy:

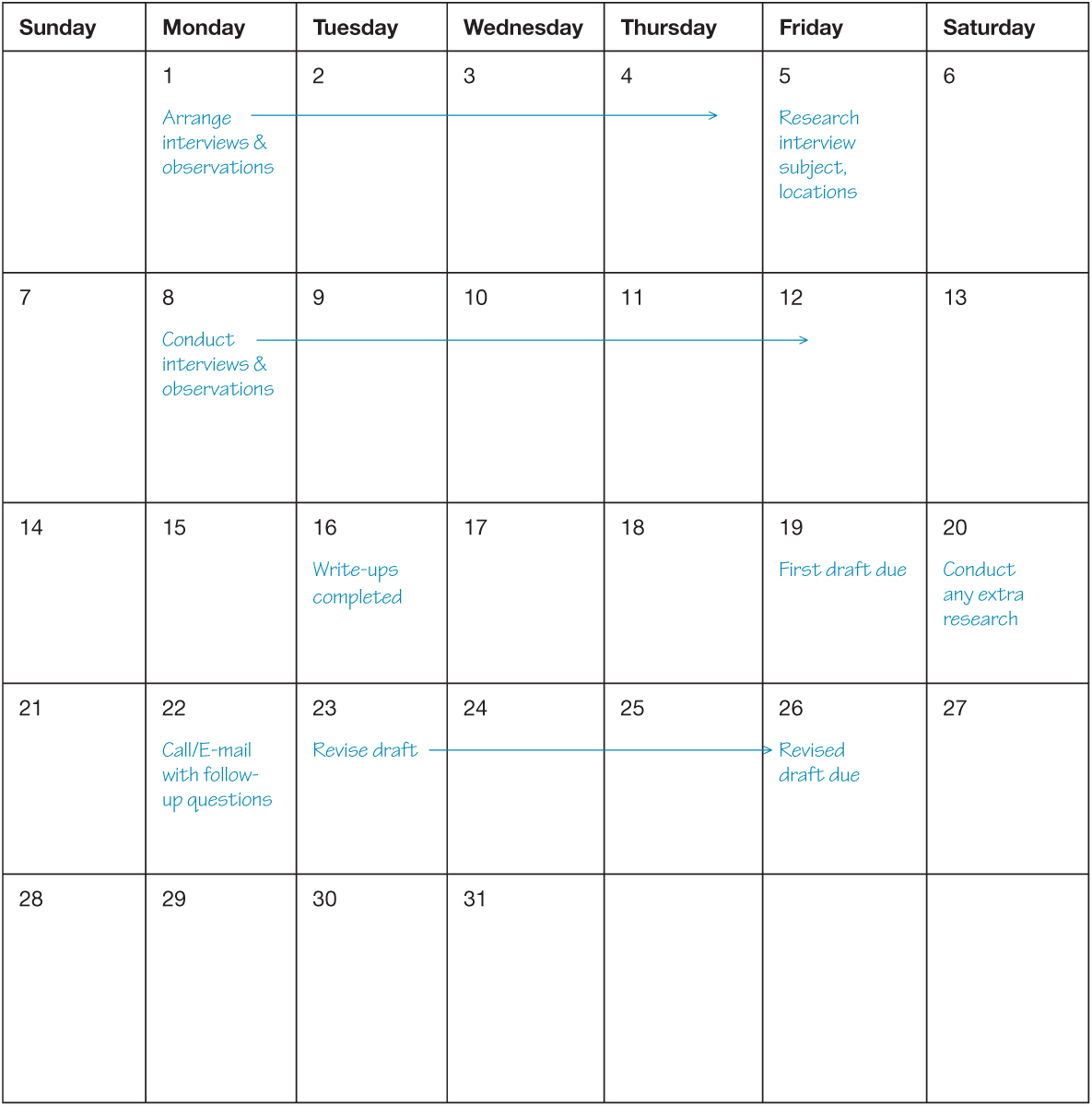

Construct a calendar marking the date the project is due and any other intermediate due dates (such as the date the first draft, thesis, or topic is due).

Work backward, adding dates by which key stages or milestones should be reached to make your due dates. For example, mark the following:

The date by which final revisions to text and images are needed

The date on which peer review is scheduled

The date by which the first draft should be completed

The date by which initial interviews and observations should be conducted (Leave at least a week for this process.)

The date by which interviews and observations must be scheduled (Leave at least several days for this process.)

WAYS IN

HOW DO I SET UP AND PREPARE FOR INTERVIEWS AND OBSERVATIONS?

List the people you would like to interview or places you would like to observe. Include a number of possibilities in case your first choice doesn’t work out.

Write out your intentions and goals so you can explain them clearly to others.

Call or e-

mail for an appointment with your interview subject, or make arrangements to visit the site . Explain who you are and what you are doing. Student research projects are often embraced, but be prepared for your request to be rejected.Note: Be sure to arrange your interview or site visit as soon as possible. The most common error students report making on this assignment is waiting too long to make that first call. Be aware, too, that the people and places you contact may not respond immediately (or at all); be sure to follow up if you have not gotten an answer to your request within a few days.

Make notes about what you expect to learn before you write interview questions, interview your subject, or visit your site. Ask yourself questions like these:

Page 96Interview Observation How would I define or describe the subject?

What is the subject’s purpose or function?

Who or what is associated with it?

What about it will interest me and my readers?

What do I hope to learn about it?

How would I define or describe my subject?

What typically takes place at this location? Who or what will I likely observe?

What will interest me and my readers?

What do I expect to learn about my subject?

How will my presence affect those I am observing?

Write some interview questions in advance, or ask yourself some observation questions to help you determine how best to conduct your site visit.

Interview Observation Ask for stories:

Tell me how you got into .................... .

Tell me about something that surprised/pleased/frustrated you.

Let subjects correct misconceptions:

What myths about .................... would you most like to bust?

Ask about the subject’s past and future:

How has .................... changed over the years, and where do you think it’s going?

Consider your PERSPECTIVE: Should I observe from different vantage points or from the same location?

Should I visit the location at different times of day or days of the week, or would it be better to visit at the same time every day?

Should I focus on specific people, or should I identify roles and focus on people as they adopt those roles?

Conduct some preliminary research on your subject or related subjects if possible, and revise your questions or plans accordingly.

WAYS IN

|

HOW DO I CONDUCT INTERVIEWS? |

HOW DO I CONDUCT OBSERVATIONS? |

|

Take notes:

Reflect on the interview. Review your notes right after the interview, adding any impressions and marking promising material, such as

Write up your interview. Write a few paragraphs reporting what you learned from the interview:

Do follow-

|

Take notes:

Consider your ROLE:

Collect artifacts, or take videos or photos:

Reflect on your observations. Take five minutes right after your visit to think about what you observed, and write a few sentences about your impressions of the subject: Page 98

Write up your observations:

Consider whether you need a follow-

|

WAYS IN

HOW SHOULD I PRESENT THE INFORMATION I’VE GLEANED FROM INTERVIEWS AND OBSERVATIONS?

Review the notes from your interviews and observations, selecting the information to include in your draft and how you might present it. Consider including the following:

DEFINITIONS of key terms readers will find unfamiliar;

COMPARISONS or CONTRASTS that make information clearer or more memorable;

LISTS or CATEGORIES that organize information logically;

PROCESSES that readers will find interesting or surprising.

Use quotations that provide information and reveal character.

Good profiles quote sources so readers can hear what people have to say in their own voices. The most useful quotations are those that reveal the style and character of the people you interviewed. Speaker tags (like she said, he asked) help readers determine the source of a quotation. You may rely on an all-

“Try this one,” he says. (Thompson, par. 7)

“Take me out to the”—and Toby yells out, “Banana store!” (Coyne, par. 21)

Adding a word or phrase to a speaker tag can reveal something relevant about the speaker’s manner or provide context:

“We’re in Ripley’s Believe It or Not, along with another funeral home whose owners’ names are Baggit and Sackit,” Howard told me, without cracking a smile. (Cable, par. 14)

Once, after being given this weak explanation, he said, “I wish I could have done something really bad, like my Mommy. So I could go to prison too and be with her.” (Coyne, par. 18)

“Describe how you’re feeling with twenty corned-

In addition to being carefully introduced, quotations must be precisely punctuated. Fortunately, there are only two general rules:

Enclose all quotations in a pair of quotation marks, one at the beginning and one at the end of the quotation.

For more about integrating quotations, see Chapter 23 , “Using Information from Sources to Support Your Claims.”

Separate the quotation from its speaker tag with appropriate punctuation, usually a comma. (Commas and periods usually go inside the closing quotation mark, but question marks go inside or outside, depending on whether the question is the speaker’s or the writer’s.) If you have more than one sentence (as in the last example above), be careful to punctuate the separate sentences properly.

Consider adding visual or audio elements.

Think about whether visual or audio elements—

Note: Be sure to cite the source of visual or audio elements you didn’t create, and get permission from the source if your profile is going to be published on a Web site that is not password protected.

Create an outline that will organize your profile effectively for your readers.

For more on clustering and outlining, see Chapter 11, “Mapping.”

Here are two sample outlines you can modify to fit your needs, depending on whether you prefer a narrative plan (to give a tour of a place, for example) or a topical plan (to cluster related information). Even if you wish to blend features of both outlines, seeing how each basic plan works can help you combine them. Remember that each section need not be the same length; some sections may require greater detail than others.

| Narrative Plan | Topical Plan |

|

|

The tentative plan you choose should reflect the possibilities in your material as well as your purpose and your understanding of your audience. When using a narrative plan, use verb tenses and transitions of space and time to make the succession of events clear; when using a topical plan, use logical transitions to help readers move from topic to topic. As you draft, you will almost certainly discover new ways of organizing parts of your material.

Determine your role in the profile.

Consider the advantages and disadvantages of the spectator and participant-

WAYS IN

WHICH ROLE WILL BEST HELP ME CONVEY THE EXPERIENCE OF MY PROFILE SUBJECT?

Choose the SPECTATOR ROLE to:

provide readers with a detailed description or guided tour of the scene.

X was dressed in .................... with .................... and .................... , doing .................... as s/he .................... -ed.

Inside, you could see .................... . The room was .................... and .................... .

| EXAMPLE | The door was massive, yet it swung open easily on well- |

create an aura of objectivity, making it appear as though you’re just reporting what you see and hear without revealing that you have actually made choices about what to include in order to create a DOMINANT IMPRESSION.

The shiny new/rusty old tools were laid out neatly/piled helter skelter on the workbench, like .................... .

| EXAMPLE | The juice drips down their arms, saturating their shirts. Their puffed- |

Caution: The SPECTATOR ROLE may cause readers to:

feel detached, which can lead to a lack of interest in the subject profiled;

suspect a hidden bias behind the appearance of objectivity, undermining the writer’s credibility.

Choose the PARTICIPANT-

profile physical activities through the eyes of a novice, so readers can imagine doing the activity themselves.

I picked up the .................... . It felt like .................... and smelled/tasted/sounded like .................... .

| EXAMPLE | The greatest difficulty, though, is in the trimming. I had no idea that a head of lettuce was so humongous. In order to get it into a shape that can be bagged, I trim and trim and trim. . . . |

reveal how others react to you.

X interrupted me as I ....................-ed.

As I struggled with .................... , Y noticed and .................... -ed.

| EXAMPLE | People whose names I didn’t yet know would ask me how I was holding up, reminding me that it would get easier as time went by. (Thompson, par. 14) |

Caution: The PARTICIPANT-

wonder whether your experience was unique to you, not something they would have experienced;

think the person, place, group, or activity being profiled seemed secondary in relation to the writer’s experience.

Develop your perspective on the subject.

Try some of these activities to deepen your analysis and enhance your readers’ understanding of your subject’s cultural significance.

WAYS IN

HOW CAN I DEVELOP A PERSPECTIVE FOR MY PROFILE?

Explore the CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE of your subject:

If you are focusing on a place (like a mortuary or prison visiting room), consider what intrigues you about its culture by asking yourself questions like these:

Who are the insiders at this place and why are they there?

How does the place affect how insiders talk, act, think, feel?

What function does the place serve in the wider community?

What tensions are there between insiders and outsiders or between newcomers and veterans?

X and Y say .................... and .................... because they want to .................... , but they seem to feel .................... because of the way they do .................... .

| EXAMPLE | And I can imagine the hours spent preparing for this visit. . . . |

If you are focusing on an activity (like eating competitively or cutting lettuce), ask yourself questions like these:

Who benefits from it?

What value does it have for the insider community and for the wider community?

How has the activity or process changed over time, for good or ill?

How are outsiders initiated into the activity?

It’s important to recognize .................... because .................... .

.................... [date or event] marked a turning point because .................... .

| EXAMPLE | July 4, 2001— |

If you are focusing on a person or group of people, ask yourself questions like these:

What sense of identity do they have?

What customs and ways of communicating do they have?

What are their values and attitudes?

What are their social hierarchies and what do they think about them?

How do they see their role in the community?

X values/believes .................... , as you can see from the way s/he .................... .

Members of group X are more likely to .................... than people in the general population because .................... .

| EXAMPLES |

He said that he felt people were becoming more aware of the public service his profession provides. (Cable, par. 27) He’s settled on an exact combination of specific brands of olive and fish oils, but he won’t divulge more. “I had to figure it out,” he said, “so why should I let it be known?” (Ronson, par. 8) |

Define your PURPOSE and AUDIENCE. Write for five minutes exploring what you want your readers to learn about the subject and why. Use sentence strategies like these to help clarify your thinking:

In addition to my teacher and classmates, I envision my ideal readers as .................... .

They probably know .................... about my subject and believe .................... .

They would be most surprised to learn .................... and most interested in .................... .

I can help change their opinions of X by .................... and get them to think about X’s social and cultural significance by .................... .

State your main point. Review what you have written, and summarize in a sentence or two the main idea you want readers to take away from your profile. Readers don’t expect a profile to have an explicit thesis statement, but the descriptive details and other information need to work together to convey the main idea.

Clarify the dominant impression.

The descriptive details, comparisons, and word choices you use and the information you supply should reinforce the dominant impression you are trying to create. For example, the dominant impression of Cable’s profile is his—

WAYS IN

HOW DO I FINE-

Identify your intended DOMINANT IMPRESSION. Write for five minutes sketching out the overall impression you want readers to take away from your profile. What do you want readers to think and feel about your subject?

Reread your notes and write-

If your initial dominant impression seems too simplistic, look for any contradictions or gaps in your notes and write-

Although X clearly seemed .................... , I couldn’t shake the feeling that .................... .

Although Y tries to/pretends to .................... , overall/primarily he/she/it .................... .

Write the opening sentences.

Review your invention writing to see if you have already written something that would work to launch your essay or try some of these opening strategies:

Begin with an arresting scene:

You can spot the convict-

Offer a remarkable thought or occasion that triggered your observational visit:

Death is a subject largely ignored by the living. (Cable, par. 1)

Start with a vivid description:

Here is a mountain of corned-

But don’t agonize over the first sentences because you are likely to discover the best way to begin only as you draft your essay.

Draft your profile.

By this point, you have done a lot of research and writing

to develop something interesting to say about a subject;

to devise a plan for presenting that information;

to identify a role for yourself in the essay;

to explore your perspective on the subject.

Now stitch that material together to create a draft. The next two parts of this Guide to Writing will help you evaluate and improve your draft.