Instructor's Notes

- The “Make Connections” activity can be used as a discussion board prompt by clicking on “Add to This Unit,” selecting “Create New,” choosing “Discussion Board,” and then pasting the “Make Connections” activity into the text box.

- The basic features (“Analyze and Write”) activities following this reading, as well as an autograded multiple-

choice quiz, a summary activity with a sample summary as feedback, and a synthesis activity for this reading, can be assigned by clicking on the “Browse Resources for the Unit” button or navigating to the “Resources” panel.

John Tierney Do You Suffer from Decision Fatigue?

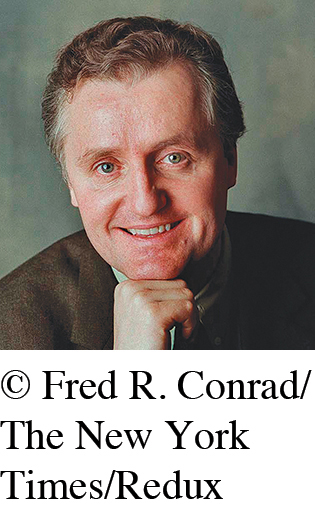

JOHN TIERNEY has been a columnist for The New York Times since 1990, where he has worked as a general assignment reporter and a regular columnist, writing for The New York Times Magazine and for the Metro section in a column called “The Big City.” Currently he writes a column, “Findings,” for the Science Times section. He has worked for several other magazines and newspapers, among them The Atlantic, Discover, Esquire, Newsweek, Outside, and The Wall Street Journal. In collaboration with novelist Christopher Buckley, Tierney co-

As you read,

Think about the effectiveness of the opening scenario that describes the decisions made by the parole board. What is Tierney’s purpose in starting with this anecdote?

Ponder the relationship you see between decision fatigue and willpower.

1

T hree men doing time in Israeli prisons recently appeared before a parole board consisting of a judge, a criminologist and a social worker. The three prisoners had completed at least two-

Case 1 (heard at 8:50 a.m.): An Arab Israeli serving a 30-

Case 2 (heard at 3:10 p.m.): A Jewish Israeli serving a 16-

Case 3 (heard at 4:25 p.m.): An Arab Israeli serving a 30-

2

There was a pattern to the parole board’s decisions, but it wasn’t related to the men’s ethnic backgrounds, crimes or sentences. It was all about timing, as researchers discovered by analyzing more than 1,100 decisions over the course of a year. Judges, who would hear the prisoners’ appeals and then get advice from the other members of the board, approved parole in about a third of the cases, but the probability of being paroled fluctuated wildly throughout the day. Prisoners who appeared early in the morning received parole about 70 percent of the time, while those who appeared late in the day were paroled less than 10 percent of the time.

3

The odds favored the prisoner who appeared at 8:50 a.m. — and he did in fact receive parole. But even though the other Arab Israeli prisoner was serving the same sentence for the same crime — fraud — the odds were against him when he appeared (on a different day) at 4:25 in the afternoon. He was denied parole, as was the Jewish Israeli prisoner at 3:10 p.m, whose sentence was shorter than that of the man who was released. They were just asking for parole at the wrong time of day.

4

There was nothing malicious or even unusual about the judges’ behavior, which was reported . . . by Jonathan Levav of Stanford and Shai Danziger of Ben-Gurion University. The judges’ erratic judgment was due to the occupational hazard of being, as George W. Bush once put it, “the decider.” The mental work of ruling on case after case, whatever the individual merits, wore them down. This sort of decision fatigue can make quarterbacks prone to dubious choices late in the game and C.F.O.’s prone to disastrous dalliances late in the evening. It routinely warps the judgment of everyone, executive and nonexecutive, rich and poor — in fact, it can take a special toll on the poor. Yet few people are even aware of it, and researchers are only beginning to understand why it happens and how to counteract it.

5

Decision fatigue helps explain why ordinarily sensible people get angry at colleagues and families, splurge on clothes, buy junk food at the supermarket and can’t resist the dealer’s offer to rustproof their new car. No matter how rational and high-

When people fended off the temptation to scarf down M&M’s or freshly baked chocolate-

6

Decision fatigue is the newest discovery involving a phenomenon called ego depletion, a term coined by the social psychologist Roy F. Baumeister . . . [who] began studying mental discipline in a series of experiments, first at Case Western and then at Florida State University. These experiments demonstrated that there is a finite store of mental energy for exerting self-

7

But then a postdoctoral fellow, Jean Twenge, started working at Baumeister’s laboratory right after planning her wedding. As Twenge studied the results of the lab’s ego-

8

“By the end, you could have talked me into anything,” Twenge told her new colleagues. The symptoms sounded familiar to them too, and gave them an idea. A nearby department store was holding a going-

9

Afterward, all the participants were given one of the classic tests of self-

10

Any decision, whether it’s what pants to buy or whether to start a war, can be broken down into what psychologists call the Rubicon model of action phases, in honor of the river that separated Italy from the Roman province of Gaul. When Caesar reached it in 49 BC, on his way home after conquering the Gauls, he knew that a general returning to Rome was forbidden to take his legions across the river with him, lest it be considered an invasion of Rome. Waiting on the Gaul side of the river, he was in the “predecisional phase” as he contemplated the risks and benefits of starting a civil war. Then he stopped calculating and crossed the Rubicon, reaching the “postdecisional phase,” which Caesar defined much more felicitously: “The die is cast.”

11

The whole process could deplete anyone’s willpower, but which phase of the decision-

12

Once you’re mentally depleted, you become reluctant to make trade-

13

Decision fatigue leaves you vulnerable to marketers who know how to time their sales, as Jonathan Levav, the Stanford professor, demonstrated in experiments involving . . . new cars. . . .

14

It’s simple enough to imagine reforms for the parole board in Israel — like, say, restricting each judge’s shift to half a day, preferably in the morning, interspersed with frequent breaks for food and rest. But it’s not so obvious what to do with the decision fatigue affecting the rest of society. . . .

[REFLECT]

Make connections: Your own experience with decision fatigue.

Tierney writes about a judge whose fairness is undermined by decision fatigue. Think about your own experience making decisions. Have you ever made a decision that you regretted or avoided making a decision when decisiveness was important? Your instructor may ask you to post your thoughts on a class discussion board or to discuss them with other students in class. Use these questions to get started:

Think about a decision that you regretted making (or not making). How may decision fatigue have influenced you? What else might have influenced your decision (for example, peer pressure or fear of disappointing a loved one)?

Tierney points out that it would be easy to reform the schedule of the parole board to take the decision fatigue out of their day, but that “it’s not so obvious what to do with the decision fatigue affecting the rest of society” (par. 14). What steps could you take to ease decision fatigue? How would society change if we all had fewer decisions to make? What would we gain, and what would we be giving up?

[ANALYZE]

Use the basic features.

A FOCUSED EXPLANATION: USING AN EXAMPLE

Examples often play a central role in writing about concepts because concepts are general and abstract, and examples help make them specific and concrete. Examples can also be very useful tools for focusing an explanation. Toufexis, for example, uses examples of popular films (Bram Stoker’s Dracula, The Seven-

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing how Tierney uses the example of one judge deciding the fate of three prisoners to illustrate the concept of decision fatigue in “Do you Suffer from Decision Fatigue?”:

Skim paragraphs 1–4. How do they help readers understand the concept of decision fatigue?

Now look back at paragraph 4. How does this paragraph answer the “So what?” question readers of concept explanations inevitably ask? In other words, how does it provide a focus for Tierney’s explanation of the concept and help readers grasp why the concept is important?

Finally, reread paragraph 13, in which Tierney explains how marketers use decision fatigue. Why do you suppose Tierney includes this information in his explanation of the concept?

A CLEAR, LOGICAL ORGANIZATION: CREATING COHESION

Cohesive devices help readers move from paragraph to paragraph and section to section without losing the thread. The most familiar cohesive device is probably the transitional word or phrase (however, next), which alerts readers to the relationship among ideas. A less familiar, but equally effective strategy, is to repeat key terms and their synonyms or to use pronouns (it, they) to refer to the key term. A third strategy is to provide cohesion by referring back to earlier examples, often bringing a selection full circle by referring to an opening example at the end of the essay.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph or two analyzing how Tierney creates cohesion in “Do you Suffer from Decision Fatigue?”:

Skim paragraphs 1–4, marking every word (or number) related to time. How does Tierney use time to lend cohesion to his essay? How effectively does this strategy help readers navigate this essay and understand its main point?

Select a series of three or four paragraphs and analyze how Tierney knits the paragraphs together. Can you identify any repeated words or concepts, or any pronouns that refer to terms in the preceding paragraph? Does Tierney use transitional words or phrases to link one paragraph to the next?

Finally, reread the last paragraph. How does Tierney lend closure to his essay? How effective is his strategy?

APPROPRIATE EXPLANATORY STRATEGIES: USING A VARIETY OF STRATEGIES

Writers typically use a variety of strategies to explain a concept. Potthast, for example, defines the concept of supervolcano, classifies the historic eruptions, illustrates their consequences, and explores causes and “dangerous physical effects” (par. 2) of supervolcanoes. Here are a few examples of sentence patterns Potthast uses to present some of these explanatory strategies:

Definition

| EXAMPLE | Supervolcanoes are volcanoes that produce eruptions thousands of times the size of ordinary volcanoes. (par. 1) |

X is a member of class Y with ______, ______, and [distinguishing traits].

Classification

| EXAMPLE | Volcanic eruptions feature several dangerous physical effects, including pyroclastic flows, pyroclastic surges, lahars, tephra falls, and massive amounts of fine ash particles in the air. (par. 2) |

X is made up of 3 basic parts: ______, ______, ______.

Cause-

| EXAMPLE | If a super- |

The causes of X are varied, but the most notable are ______ and ______.

The effects of X may include ______, ______, and ______.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph analyzing how Tierney uses definition, classification, cause-

Skim Tierney’s essay looking for and highlighting examples of two or three different types of explanatory strategies.

Now select one strategy that you think is particularly effective and explain why you think it works so well. What does the strategy contribute to the explanation of decision fatigue? How does it help answer the “So what?” question?

SMOOTH INTEGRATION OF SOURCES: DECIDING WHEN AND HOW TO CITE SOURCES

Writers of concept explanations nearly always conduct research; incorporate information from sources into their writing using summary, paraphrase, and quotation; and identify their sources so that readers can identify them as experts. But how they acknowledge their sources depends on the conventions of their writing situation. Toufexis, writing for Time magazine’s general audience, makes clear that her sources are experts by mentioning their credentials in signal phrases:

Says Michael Mills, a psychology professor at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles: “Love is our ancestors whispering in our ears.” (par. 2)

But she does not include a formal citation or a list of works cited at the end of the article. Sometimes Potthast uses a signal phrase to make his source’s expertise clear; sometimes he merely includes a citation in his text. But in all cases, he includes a full citation in his list of works cited because this is required when writing for an academic audience.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph or two analyzing the kinds of material Tierney incorporates from sources in “Do You Suffer from Decision Fatigue?”:

Skim the essay, highlighting places where Tierney quotes, paraphrases, or summarizes information from sources. What information does he provide to identify his sources, and how does this information help readers know the source is trustworthy? Try to determine which information comes from published sources, which from interviews, and which from Tierney’s own general knowledge of the topic.

Page 141Again skim the essay, this time looking for places where Tierney uses an exact quotation from a source. Why do you think he decided to use an exact quotation rather than merely summarizing or paraphrasing the idea?

Finally, think about the purpose of citing sources. Why is simply identifying sources with a word or two in the text generally sufficient for nonacademic situations, while academic writing situations require in-

text citations and a list of sources? Given your experience reading online, do you think hyperlinks should replace formal citations? Why or why not?

[RESPOND]

Consider possible topics: Examining how emotions influence behavior.

Because behavioral research can help us understand ourselves in new ways, essays that shed light on psychological phenomena can be fascinating to readers. A writer could explore cognitive dissonance, the foot-