Writing Clear, Informative Paragraphs

There are two kinds of paragraphs—body paragraphs and transitional paragraphs—both of which play an important role in helping you emphasize important information.

A body paragraph, the basic unit for communicating information, is a group of sentences (or sometimes a single sentence) that is complete and self-sufficient and that contributes to a larger discussion. In an effective paragraph, all the sentences clearly and directly articulate one main point, either by introducing the point or by providing support for it. In addition, the whole paragraph follows logically from the material that precedes it.

Revising Headings

Follow these four suggestions to make your headings more effective.

For more about noun strings, see “Choosing the Right Words and Phrases.”

Avoid long noun strings. The following example is ambiguous and hard to understand:

Proposed Production Enhancement Strategies Analysis Techniques

Is the heading introducing a discussion of techniques for analyzing strategies that have been proposed? Or is it introducing a discussion that proposes using certain techniques to analyze strategies? Readers shouldn’t have to ask such questions. Adding prepositions makes the heading clearer:

Techniques for Analyzing the Proposed Strategies for Enhancing Production

This heading announces more clearly that the discussion describes techniques for analyzing strategies, that those strategies have been proposed, and that the strategies are aimed at enhancing production. It’s a longer heading than the original, but that’s okay. It’s also much clearer.

Be informative. In the preceding example, you could add information about how many techniques will be described:

Three Techniques for Analyzing the Proposed Strategies for Enhancing Production

You can go one step further by indicating what you wish to say about the three techniques:

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Three Techniques for Analyzing the Proposed Strategies for Enhancing Production

Again, don’t worry if the heading seems long; clarity is more important than conciseness.

Use a grammatical form appropriate to your audience. The question form works well for readers who are not knowledgeable about the subject (Benson, 1985) and for nonnative speakers:

What Are the Three Techniques for Analyzing the Proposed Strategies for Enhancing Production?

The “how-to” form is best for instructional material, such as manuals:

How To Analyze the Proposed Strategies for Enhancing Production

The gerund form (-ing) works well for discussions and descriptions of processes:

Analyzing the Proposed Strategies for Enhancing Production

For more about how to format headings, see “Designing Print Documents” in Ch. 7.

Avoid back-to-back headings. Use advance organizers to separate the headings.

A transitional paragraph helps readers move from one major point to another. Like a body paragraph, it can consist of a group of sentences or be a single sentence. Usually it summarizes the previous point, introduces the next point, and helps readers understand how the two are related.

The following example of a transitional paragraph appeared in a discussion of how a company plans to use this year’s net proceeds.

The first sentence contains the word “then” to signal that it introduces a summary.

The final sentence clearly indicates the relationship between what precedes it and what follows it.

Our best estimate of how we will use these net proceeds, then, is to develop a second data center and increase our marketing efforts. We base this estimate on our current plans and on projections of anticipated expenditures. However, at this time we cannot precisely determine the exact cost of these activities. Our actual expenditures may exceed what we’ve predicted, making it necessary or advisable to reallocate the net proceeds within the two uses (data center and marketing) or to use portions of the net proceeds for other purposes. The most likely uses appear to be reducing short-term debt and addressing salary inequities among software developers; each of these uses is discussed below, including their respective advantages and disadvantages.

STRUCTURE PARAGRAPHS CLEARLY

Most paragraphs consist of a topic sentence and supporting information.

The Topic Sentence Because a topic sentence states, summarizes, or forecasts the main point of the paragraph, put it up front. Technical communication should be clear and easy to read, not suspenseful. If a paragraph describes a test you performed, include the result of the test in your first sentence:

The point-to-point continuity test on Cabinet 3 revealed an intermittent open circuit in the Phase 1 wiring.

Then go on to explain the details. If the paragraph describes a complicated idea, start with an overview. In other words, put the “bottom line” on top:

Mitosis is the usual method of cell division, occurring in four stages: (1) prophase, (2) metaphase, (3) anaphase, and (4) telophase.

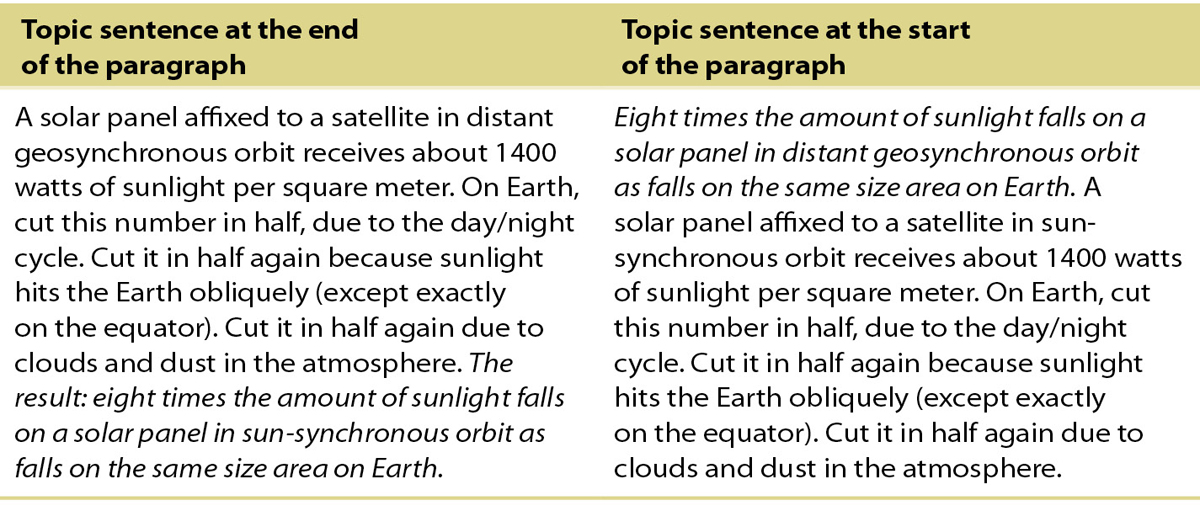

Putting the bottom line on top makes the paragraph much easier to read, as shown in Figure 6.1.

The topic sentences are italicized for emphasis in this figure.

Notice that placing the topic sentence at the start gives a focus to the paragraph, helping readers understand the information in the rest of the paragraph.

Make sure each of your topic sentences relates clearly to the organizational pattern you are using. In a discussion of the physical condition of a building, for example, you might use a spatial pattern and start a paragraph with the following topic sentence:

On the north side of Building B, water damage to about 75 percent of the roof insulation and insulation in some areas in the north wall indicates that the roof has been leaking for some time. The leaking has contributed to . . .

Your next paragraph should begin with a topic sentence that continues the spatial organizational pattern:

On the east side of the building, a downspout has eroded the lawn and has caused a small silt deposit to form on the neighboring property directly to the east. Riprap should be placed under the spout to . . .

Note that the phrases “on the north side” and “on the east side” signal that the discussion is following the points of the compass in a clockwise direction, further emphasizing the spatial pattern. Readers can reasonably assume that the next two parts of the discussion will be about the south side of the building and the west side, in that order.

Similarly, if your first topic sentence is “First, we need to . . . ,” your next topic sentence should refer to the chronological pattern: “Second, we should . . . .” (Of course, sometimes well-written headings can make such references to the organizational pattern unnecessary, as when headings are numbered to emphasize that the material is arranged in a chronological pattern.)

The Supporting Information The supporting information makes the topic sentence clear and convincing. Sometimes a few explanatory details provide all the support you need. At other times, however, you need a lot of information to clarify a difficult thought or to defend a controversial idea. How much supporting information to provide also depends on your audience and purpose. Readers knowledgeable about your subject may require little supporting information; less-knowledgeable readers might require a lot. Likewise, you may need to provide little supporting information if your purpose is merely to state a controversial point of view rather than persuade your reader to agree with it. In deciding such matters, your best bet is to be generous with your supporting information. Paragraphs with too little support are far more common than paragraphs with too much.

Supporting information, which is most often developed using the basic patterns of organization discussed earlier in this chapter, usually fulfills one of these five roles:

It defines a key term or idea included in the topic sentence.

It provides examples or illustrations of the situation described in the topic sentence.

It identifies causes: factors that led to the situation.

It defines effects: implications of the situation.

It supports the claim made in the topic sentence.

A topic sentence is like a promise to readers. At the very least, when you write a topic sentence that says “Within five years, the City of McCall will need to upgrade its wastewater-treatment facilities because of increased demands from a rapidly rising population,” you are implicitly promising readers that the paragraph not only will be about wastewater-treatment facilities but also will explain that the rapidly rising population is the reason the facilities need to be upgraded. If your paragraph fails to discuss these things, it has failed to deliver on the promise you made. If the paragraph discusses these things but also goes on to speculate about the price of concrete over the next five years, it is delivering on promises that the topic sentence never made. In both situations, the paragraph has gone astray.

Paragraph Length How long should a paragraph be? In general, 75 to 125 words are enough for a topic sentence and four or five supporting sentences. Long paragraphs are more difficult to read than short paragraphs because they require more focused concentration. They can also intimidate some readers, who might skip over them.

ETHICS NOTE

AVOIDING BURYING BAD NEWS IN PARAGRAPHS

The most-emphatic location in a paragraph is the topic sentence, usually the first sentence in a paragraph. The second-most-emphatic location is the end of the paragraph. Do not bury bad news in the middle of the paragraph, hoping readers won’t see it. It would be misleading to structure a paragraph like this:

The writer has buried the bad news in a paragraph beginning with a topic sentence that appears to suggest good news. The last sentence, too, suggests good news.

In our proposal, we stated that the project would be completed by May. In making this projection, we used the same algorithms that we have used successfully for more than 14 years. In this case, however, the projection was not realized, due to several factors beyond our control. . . . We have since completed the project satisfactorily and believe strongly that this missed deadline was an anomaly that is unlikely to be repeated. In fact, we have beaten every other deadline for projects this fiscal year.

A more forthright approach would be as follows:

Here the writer forthrightly presents the bad news in a topic sentence. Then he creates a separate paragraph with the good news.

We missed our May deadline for completing the project. Although we derived this schedule using the same algorithms that we have used successfully for more than 14 years, several factors, including especially bad weather at the site, delayed the construction. . . .

However, we have since completed the project satisfactorily and believe strongly that this missed deadline was an anomaly that is unlikely to be repeated. . . . In fact, we have beaten every other deadline for projects this fiscal year.

Dividing Long Paragraphs

Here are three techniques for dividing long paragraphs.

Break the discussion at a logical place. The most logical place to divide this material is at the introduction of the second factor. Because the paragraphs are still relatively long and cues are minimal, this strategy should be reserved for skilled readers.

High-tech companies have been moving their operations to the suburbs for two main reasons: cheaper, more modern space and a better labor pool. A new office complex in the suburbs will charge from one-half to two-thirds of the rent charged for the same square footage in the city. And that money goes a lot further, too. The new office complexes are bright and airy; new office space is already wired for computers; and exercise clubs, shopping centers, and even libraries are often on-site.

The second major factor attracting high-tech companies to the suburbs is the availability of experienced labor. Office workers and middle managers are abundant. In addition, the engineers and executives, who tend to live in the suburbs anyway, are happy to forgo the commuting, the city wage taxes, and the noise and stress of city life.

Make the topic sentence a separate paragraph and break up the supporting information. This version is easier to understand than the one above because the brief paragraph at the start clearly introduces the information. In addition, each of the two main paragraphs now has a clear topic sentence.

High-tech companies have been moving their operations to the suburbs for two main reasons: cheaper, more modern space and a better labor pool.

First, office space is a bargain in the suburbs. A new office complex in the suburbs will charge from one-half to two-thirds of the rent charged for the same square footage in the city. And that money goes a lot further, too. The new office complexes are bright and airy; new office space is already wired for computers; and exercise clubs, shopping centers, and even libraries are often on-site.

Second, experienced labor is plentiful. Office workers and middle managers are abundant. In addition, the engineers and executives, who tend to live in the suburbs anyway, are happy to forgo the commuting, the city wage taxes, and the noise and stress of city life.

Use a list. This is the easiest of the three versions for all readers because of the extra visual cues provided by the list format.

High-tech companies have been moving their operations to the suburbs for two main reasons:

Cheaper, more modern space. Office space is a bargain in the suburbs. A new office complex in the suburbs will charge anywhere from one-half to two-thirds of the rent charged for the same square footage in the city. And that money goes a lot further, too. The new office complexes are bright and airy; new office space is already wired for computers; and exercise clubs, shopping centers, and even libraries are often on-site.

A better labor pool. Office workers and middle managers are abundant. In addition, the engineers and executives, who tend to live in the suburbs anyway, are happy to forgo the commuting, the city wage taxes, and the noise and stress of city life.

But don’t let arbitrary guidelines about length take precedence over your own analysis of the audience and purpose. You might need only one or two sentences to introduce a graphic, for example. Transitional paragraphs are also likely to be quite short. If a brief paragraph fulfills its function, let it be. Do not combine two ideas in one paragraph simply to achieve a minimum word count.

You may need to break up your discussion of one idea into two or more paragraphs. An idea that requires 200 or 300 words to develop should probably not be squeezed into one paragraph.

A note about one-sentence paragraphs: body paragraphs and transitional paragraphs alike can consist of a single sentence. However, many single-sentence paragraphs are likely to need revision. Sometimes the idea in that sentence belongs with the paragraph immediately before it or immediately after it or in another paragraph elsewhere in the document. Sometimes the idea needs to be developed into a paragraph of its own. And sometimes the idea doesn’t belong in the document at all.

When you think about paragraph length, consider how the information will be printed or displayed. If the information will be presented in a narrow column, such as in a newsletter, short paragraphs are much easier to read. If the information will be presented in a wider column, readers will be able to handle a longer paragraph.

USE COHERENCE DEVICES WITHIN AND BETWEEN PARAGRAPHS

For the main idea in the topic sentence to be clear and memorable, you need to make the support—the rest of the paragraph—coherent. That is, you must link the ideas together clearly and logically, and you must express parallel ideas in parallel grammatical constructions. Even if the paragraph already moves smoothly from sentence to sentence, you can strengthen the coherence by adding transitional words and phrases, repeating key words, and using demonstrative pronouns followed by nouns.

Adding Transitional Words and Phrases Transitional words and phrases help the reader understand a discussion by explicitly stating the logical relationship between two ideas. Table 6.1 lists the most common logical relationships between two ideas and some of the common transitions that express those relationships.

Transitional words and phrases benefit both readers and writers. When a transitional word or phrase explicitly states the logical relationship between two ideas, readers don’t have to guess at what that relationship might be. Using transitional words and phrases in your writing forces you to think more deeply about the logical relationships between ideas than you might otherwise.

To better understand how transitional words and phrases benefit both reader and writer, consider the following pairs of examples:

| TABLE 6.1 Transitional Words and Phrases | |

| RELATIONSHIP | TRANSITION |

| addition | also, and, finally, first (second, etc.), furthermore, in addition, likewise, moreover, similarly |

|

|

| comparison | in the same way, likewise, similarly |

|

|

| contrast | although, but, however, in contrast, nevertheless, on the other hand, yet |

|

|

| illustration | for example, for instance, in other words, to illustrate |

|

|

| cause-effect | as a result, because, consequently, hence, so, therefore, thus |

|

|

| time or space | above, around, earlier, later, next, soon, then, to the right (left, west, etc.) |

|

|

| summary or conclusion | at last, finally, in conclusion, to conclude, to summarize |

|

|

| WEAK | Demand for flash-memory chips is down by 15 percent. We have laid off 12 production-line workers. |

| IMPROVED | Demand for flash-memory chips is down by 15 percent; as a result, we have laid off 12 production-line workers. |

| WEAK | The project was originally expected to cost $300,000. The final cost was $450,000. |

| IMPROVED | The project was originally expected to cost $300,000. However, the final cost was $450,000. |

The next sentence pair differs from the others in that the weak example does contain a transitional word, but it’s a weak transitional word:

| WEAK | According to the report from Human Resources, the employee spoke rudely to a group of customers waiting to enter the store, and he repeatedly ignored requests from co-workers to unlock the door so the customers could enter. |

| IMPROVED | According to the report from Human Resources, the employee spoke rudely to a group of customers waiting to enter the store; moreover, he repeatedly ignored requests from co-workers to unlock the door so the customers could enter. |

In the weak version, and implies simple addition: the employee did this, and then he did that. The improved version is stronger, adding to simple addition the idea that refusing to unlock the door compounded the employee’s rude behavior, elevating it to something more serious. By using moreover, the writer is saying that speaking rudely to customers was bad enough, but the employee really crossed the line when he refused to open the door.

Whichever transitional word or phrase you use, place it as close as possible to the beginning of the second idea. As shown in the examples above, the link between two ideas should be near the start of the second idea, to provide context for it. Consider the following example:

The vendor assured us that the replacement parts would be delivered in time for the product release. The parts were delivered nearly two weeks after the product release, however.

The idea of Sentence 2 stands in contrast to the idea of Sentence 1, but the reader doesn’t see the transition until the end of Sentence 2. Put the transition at the start of the second idea, where it will do the most good.

You should also use transitional words to maintain coherence between paragraphs, just as you use them to maintain coherence within paragraphs. The link between two paragraphs should be near the start of the second paragraph.

Repeating Key Words Repeating key words—usually nouns—helps readers follow the discussion. In the following example, the first version could be confusing:

| UNCLEAR | For months the project leaders carefully planned their research. The cost of the work was estimated to be over $200,000. |

| What is the work: the planning or the research? | |

| CLEAR | For months the project leaders carefully planned their research. The cost of the research was estimated to be over $200,000. |

From a misguided desire to be interesting, some writers keep changing their important terms. Plankton becomes miniature seaweed, then the ocean’s fast food. Avoid this kind of word game; it can confuse readers.

Of course, too much repetition can be boring. You can vary nonessential terms as long as you don’t sacrifice clarity.

| SLUGGISH | The purpose of the new plan is to reduce the problems we are seeing in our accounting operations. We hope to see a reduction in the problems by early next quarter. |

| BETTER | The purpose of the new plan is to reduce the problems we are seeing in our accounting operations. We hope to see an improvement by early next quarter. |

Using Demonstrative Pronouns Followed by Nouns Demonstrative pronouns—this, that, these, and those—can help you maintain the coherence of a discussion by linking ideas securely. In almost all cases, demonstrative pronouns should be followed by nouns, rather than stand alone in the sentence. In the following examples, notice that a demonstrative pronoun by itself can be vague and confusing.

| UNCLEAR | New screening techniques are being developed to combat viral infections. These are the subject of a new research effort in California. |

| What is being studied in California: new screening techniques or viral infections? | |

| CLEAR | New screening techniques are being developed to combat viral infections. These techniques are the subject of a new research effort in California. |

| UNCLEAR | The task force could not complete its study of the mine accident. This was the subject of a scathing editorial in the union newsletter. |

| What was the subject of the editorial: the mine accident or the task force’s inability to complete its study of the accident? | |

| CLEAR | The task force failed to complete its study of the mine accident. This failure was the subject of a scathing editorial in the union newsletter. |

Even when the context is clear, a demonstrative pronoun used without a noun might interrupt readers’ progress by forcing them to refer back to an earlier idea.

| INTERRUPTIVE | The law firm advised that the company initiate proceedings. This caused the company to search for a second legal opinion. |

| FLUID | The law firm advised that the company initiate proceedings. This advice caused the company to search for a second legal opinion. |