Preparing the Presentation

When you see an excellent 20-

As you start to prepare a presentation, think about ways to enlist others to help you prepare and deliver it. If possible, you should rehearse the presentation in front of others. You can also call on others to help you think about your audience and purpose, the organization of the information, the types of graphics to use, appropriate designs for slides, and so forth. The more extensively you work with other people as you plan, assemble, and rehearse, the more successful the presentation is likely to be.

Preparing an oral presentation requires five steps:

analyzing the speaking situation

organizing and developing the presentation

preparing presentation graphics

choosing effective language

rehearsing the presentation

ANALYZING THE SPEAKING SITUATION

First, analyze your audience and purpose. Then determine how much information you can deliver in the allotted time.

Analyzing Your Audience and Purpose In planning an oral presentation, consider audience and purpose, just as you would in writing a document.

Audience. What does the audience know about your subject? Your answer will help you determine the level of technical vocabulary and concepts you will use, as well as the types of graphics. Why are audience members listening to your presentation? Are they likely to be hostile, enthusiastic, or neutral? A presentation on the benefits of free trade, for instance, will be received one way by conservative economists and another way by U.S. steelworkers. Does your audience include nonnative speakers of English? If so, prepare to slow down the pace of the delivery and use simple vocabulary.

Purpose. Are you attempting to inform or to both inform and persuade? If you are explaining how wind-

turbine farms work, you will describe a process. If you are explaining why your company’s wind turbines are an economical way to generate power, you will compare them with other power sources.

Your analysis of your audience and purpose will affect the content and the form of your presentation. For example, you might have to emphasize some aspects of your subject and ignore others altogether. Or you might have to arrange topics to accommodate an audience’s needs.

| TABLE 15.1 Time Allotment for a 20- |

|

| TASK | TIME (MINUTES) |

|

2 |

|

4 4 4 |

|

2 |

|

2 |

Budgeting Your Time At most professional meetings, each speaker is given a maximum time, such as 20 minutes. If the question-

For a 20-

ORGANIZING AND DEVELOPING THE PRESENTATION

The speaking situation will help you decide how to organize and develop the information you will present.

Start by considering the organizational patterns used typically in technical communication. For instance, if you are a quality-

As you devise an effective organizational pattern for your presentation, note the kinds of information you will need for each section of the presentation. Some of this information will be data; some of it will be graphics that you can use in your presentation; some might be objects that you want to pass around in the audience. Prepare an outline of your presentation.

This is also a good time to plan the introduction and the conclusion. Like an introduction to a written document, an introduction to an oral presentation helps your audience understand what you are going to say, why you are going to say it, and how you are going to say it. The conclusion reinforces what you have said and looks to the future.

Introducing and Concluding the Presentation

In introducing a presentation, consider these five suggestions.

Introduce yourself. Unless you are speaking to colleagues you work with every day, begin with an introduction: “Good morning. My name is Omar Castillo, and I’m the Director of Facilities here at United.” If you are using slides, include your name and position on the title slide.

State the title of your presentation. Like all titles, titles of presentations should name the subject and purpose, such as “Replacing the HVAC System in Building 3: Findings from the Feasibility Study.” Include the title of your presentation on your title slide.

Explain the purpose of the presentation. This explanation can be brief: “My purpose today is to present the results of the feasibility study carried out by the Facilities Group. As you may recall, last quarter we were charged with determining whether it would be wise to replace the HVAC system in Building 3.”

State your main point. An explicit statement can help your audience understand the rest of the presentation: “Our main finding is that the HVAC system should be replaced as soon as possible. Replacing it would cost approximately $120,000. The payback period would be 2.5 years. We recommend that we start soliciting bids now, for an installation date in the third week of November.”

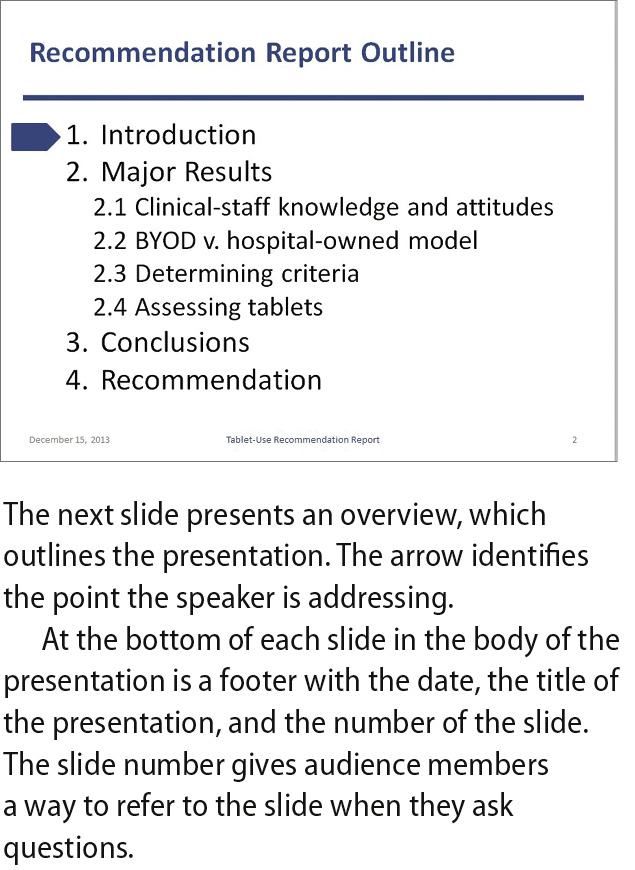

Provide an advance organizer. Listeners need an advance organizer that specifically states where you are going: “First, I’d like to describe our present system, highlighting the recent problems we have experienced. Next, I’d like to . . . . Then, I’d like to . . . . Finally, I’d like to invite your questions.”

In concluding a presentation, consider these four suggestions.

Announce that you are concluding. For example, “At this point, I’d like to conclude my talk with . . . .” This statement helps the audience focus on your conclusions.

Summarize the main points. Because listeners cannot replay what you have said, you should briefly summarize your main points. If you are using slides, you should present a slide that lists each of your main points in one short phrase.

Look to the future. If appropriate, speak briefly about what you think (or hope) will happen next: “If the president accepts our recommendation, you can expect the renovation to begin in late November. After a few hectic weeks, we’ll have the ability to control our environment much more precisely than we can now—

and start to reduce our expenses and our carbon footprint.” Invite questions politely. You want to invite questions because they help you clarify what you said or communicate information that you did not present in the formal presentation. You want to ask politely to encourage people to speak up.

PREPARING PRESENTATION GRAPHICS

Graphics clarify or highlight important ideas or facts. Statistical data, in particular, lend themselves to graphical presentation, as do abstract relationships and descriptions of equipment or processes. Researchers have known for decades that audiences remember information better if it is presented to them verbally and visually rather than only verbally (see, for instance, Fleming and Levie, 1978). Research reported by speaking coach Terry C. Smith (1991) indicates that presentations that include graphics are judged to be more professional, persuasive, and credible than those that do not. In addition, Smith notes, audiences remember the information better:

|

Retention After |

||

| 3 Hours | 3 Days | |

| Without graphics | 70% | 10% |

| With graphics | 85% | 65% |

One other advantage of using presentation graphics is that the audience is not always looking at you. Giving the audience another visual focus can reduce your nervousness.

For more about creating graphics, see Ch. 8.

Most speakers use presentation software to develop slides. By far the most-

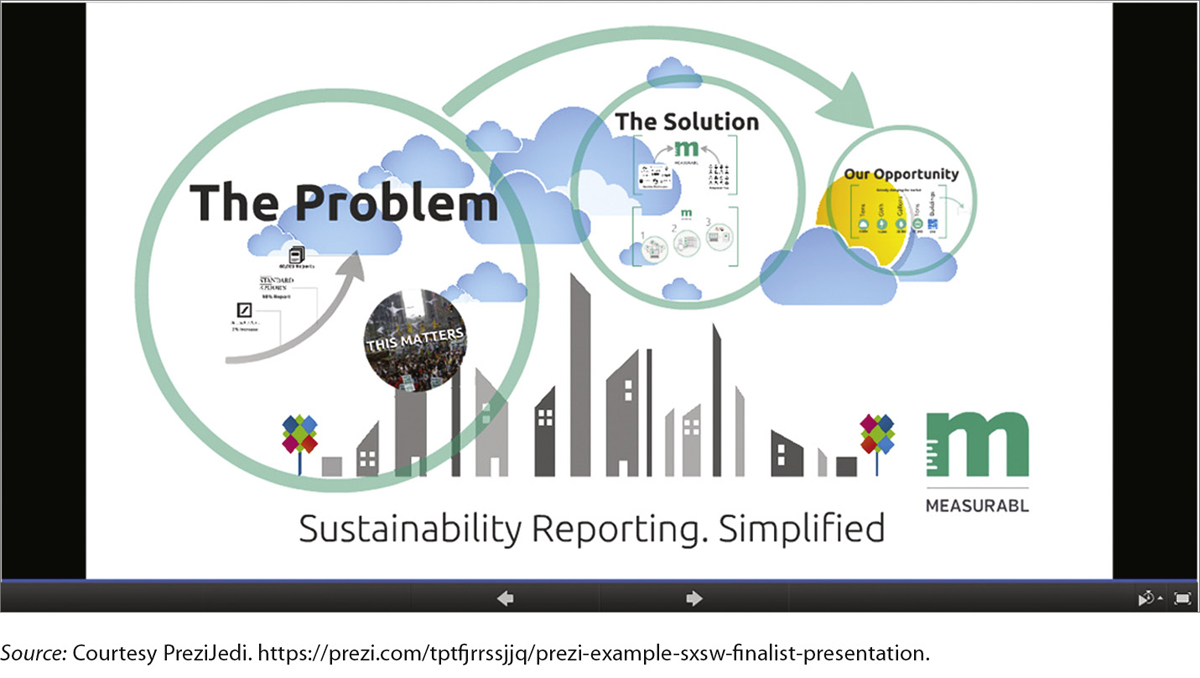

Figure 15.1 shows a frame from a Prezi presentation developed by Greg Rosner, owner of the design consultancy PreziJedi. Rosner developed it for Measurabl, a company that develops sustainability-

Rosner notes that Prezi’s zoom function makes a single Prezi suitable for presentations of varying lengths that meet the needs of different audiences. Presenters can create brief presentations, by zooming in on just a few of the frames, or longer, more-

Measurabl requested a cityscape background because it wanted to use Prezi’s navigational features to take the audience on a “journey” over a sustainably run city—

The free version of Prezi is cloud-

When you use presentation software to create a set of slides for a presentation, avoid templates, many of which violate basic design principles. For the frame shown in Figure 15.1, Rosner began with a blank Prezi canvas and shaped the presentation from a Word outline developed by Measurabl. Whichever presentation software you use, start simple and let your audience and purpose shape your design choices. In Prezi, select “Start blank Prezi” on the “Choose your template” page. In PowerPoint, create your own design on the Slide Master.

In addition to templates, many presentation software programs contain animation effects. In PowerPoint, you can set the software so that when a new slide appears, it is accompanied by the sound of applause or of breaking glass, and the heading text spins around like a pinwheel. In Prezi, you can transition between two frames by rotating the canvas by as much as 90 degrees. But unless you have a good reason to use these animation effects, don’t. Animation effects that are unrelated to your subject undercut your professionalism and quickly become tiresome.

However, one animation effect in PowerPoint, called appear and dim, is useful. When you create a bulleted list, you can set the software to show just the first bullet item and then make the next bullet item appear when you click the mouse. When you do so, the previous bullet item dims. This feature is useful because it focuses the audience’s attention on the bullet item you are discussing. Regardless of whether you are using the appear-

Characteristics of an Effective Slide An effective presentation slide has five characteristics:

It presents a clear, well-

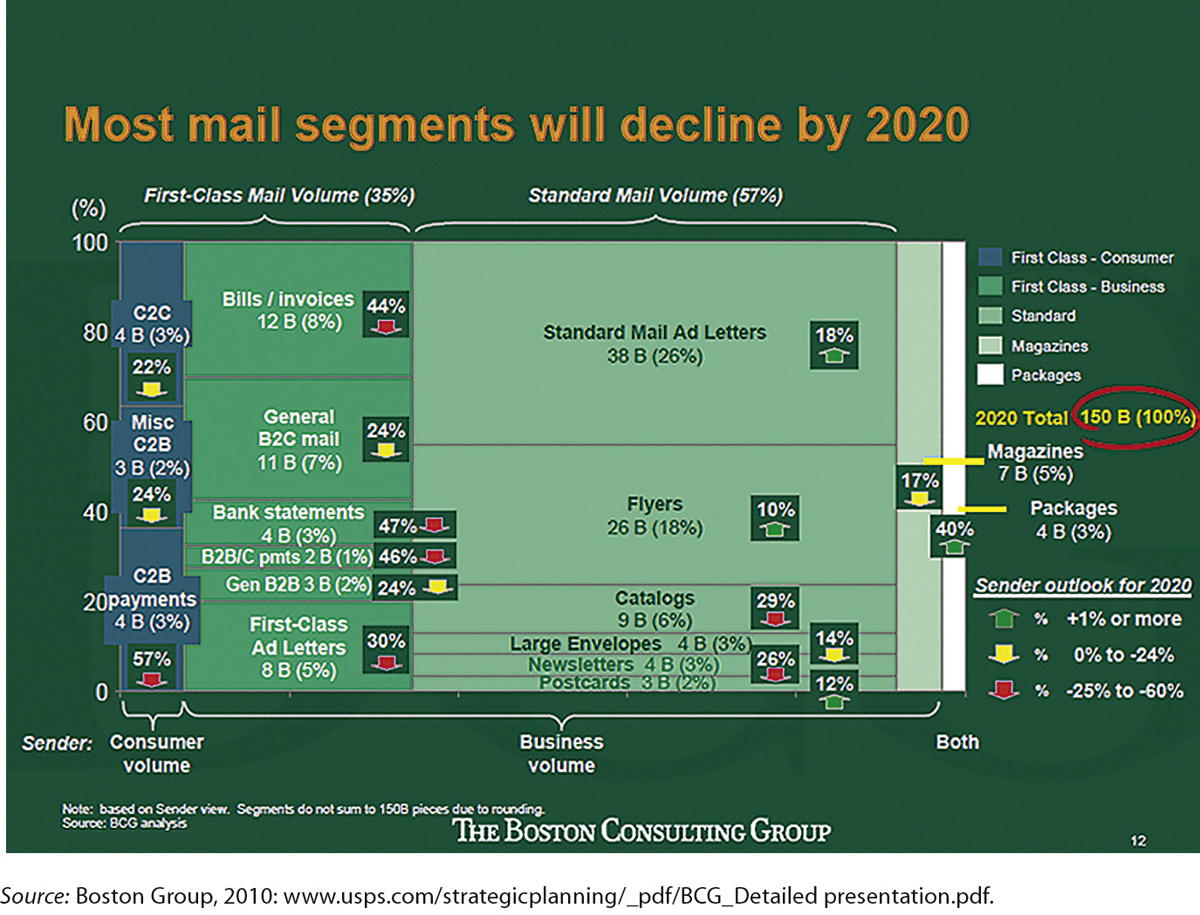

supported claim. For a slide-based presentation, engineering professor and presentation specialist Michael Alley recommends putting the claim in the headline section of the slide and the support in the body of the slide (2007). For a Prezi presentation, include a claim and its support within a single frame, using design principles to clearly identify each item for the audience. It is easy to see. The most common problem with presentation text is that it is too small. In general, text has to be in 24-

point type or larger to be visible on a screen. Figure 15.2 shows a slide containing so much information that most of it is too small to see easily.  Figure 15.2: Figure 15.2 Too Much Information on a SlideSource: Boston Group, 2010: www.usps.com/

Figure 15.2: Figure 15.2 Too Much Information on a SlideSource: Boston Group, 2010: www.usps.com/strategicplanning/ ._pdf/ BCG_Detailed presentation.pdf It is easy to read. Use clear, legible lines for drawings and diagrams; black on white works best. Use legible typefaces for text; a boldface sans-

serif typeface such as Arial or Helvetica is effective because it reproduces clearly on a screen. Avoid shadowed and outlined letters. It is simple. Each slide should present only one idea. Your listeners have not seen the graphic before and will not be able to linger over it.

It is correct. Proofread your slides carefully. Everyone makes mistakes in grammar, punctuation, or spelling, but mistakes are particularly embarrassing when they are 10 inches tall on a screen.

Graphics and the Speaking Situation To plan your graphics, analyze four aspects of the speaking situation:

-

Length of the presentation. How many slides should you have? Smith (1991) suggests showing a different slide approximately every 30 seconds of the presentation. This figure is only a guideline; base your decision on your subject and audience. Still, the general point is valid: it is far better to have a series of simple slides than to have one complicated one that stays on the screen for five minutes.

-

Audience aptitude and experience. What kinds of graphics can your audience understand easily? You don’t want to present scatter graphs, for example, if your audience does not know how to interpret them.

Size and layout of the room. Graphics to be used in a small meeting room differ from those suitable for a 500-

seat auditorium. Think first about the size of the images, then about the layout of the room. For instance, will a window create glare that you will have to consider as you plan the type or placement of the graphics? -

Equipment. Find out what kind of equipment will be available in the presentation room. Ask about backups in case of equipment failure. If possible, bring your own equipment—

then you can be confident that the equipment works and you know how to use it. Some speakers bring graphics in two media just in case; that is, they have slides, but they also have transparencies of the same graphics. If your presentation is going to be recorded to be made available on a website or as a podcast, try to arrange to have the recording technicians visit the site beforehand to see if there are any problems they will need to solve.

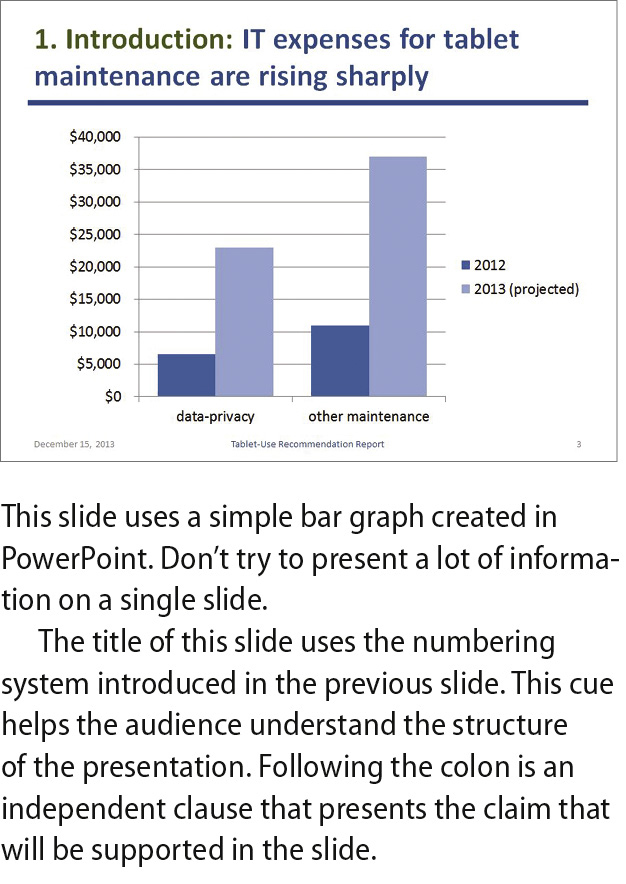

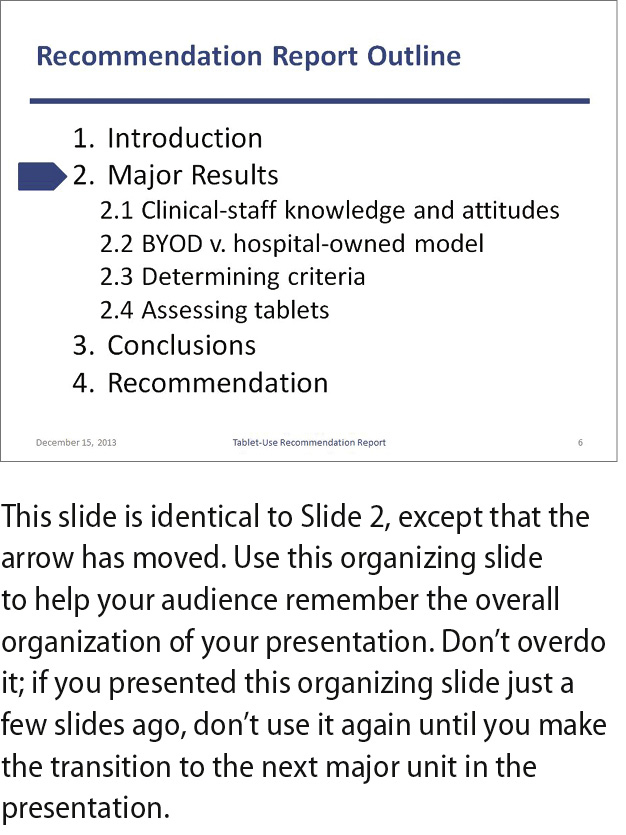

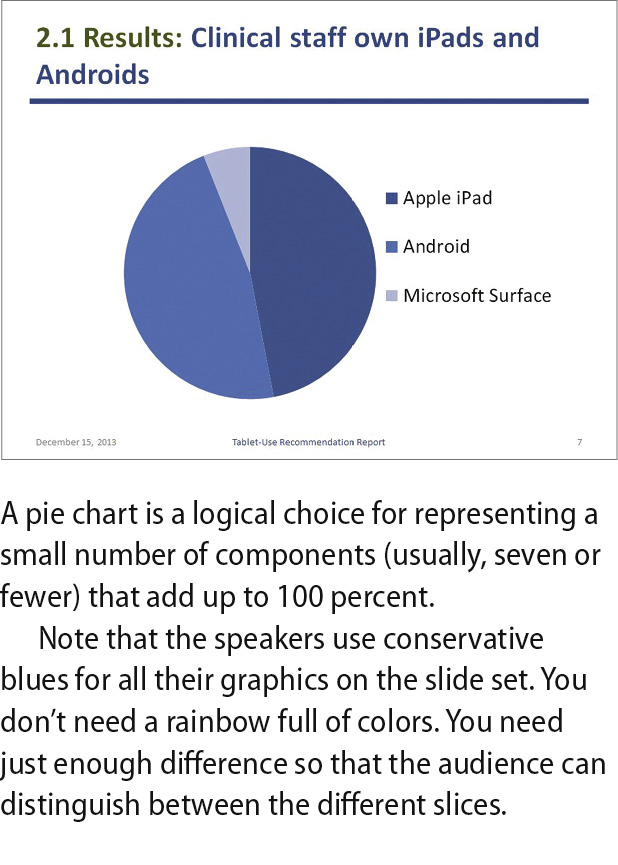

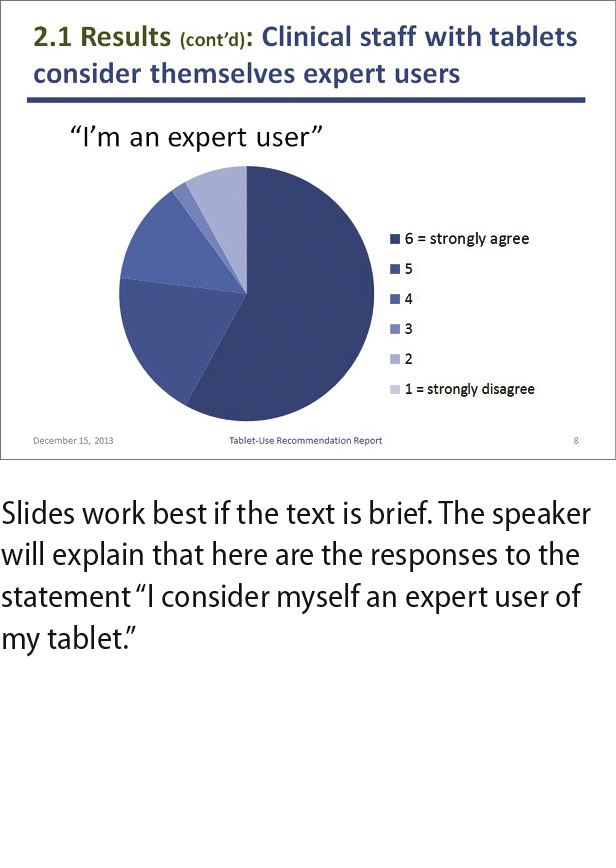

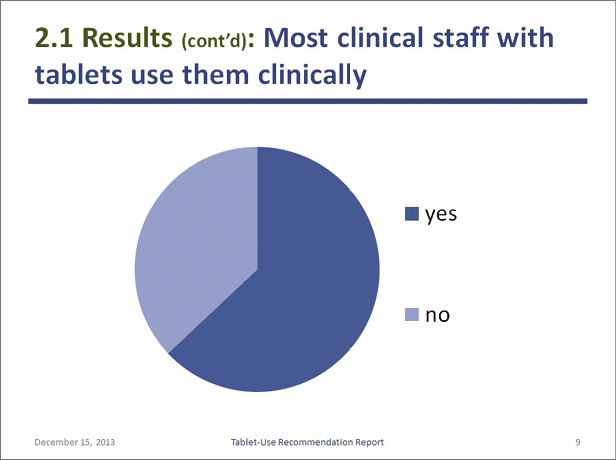

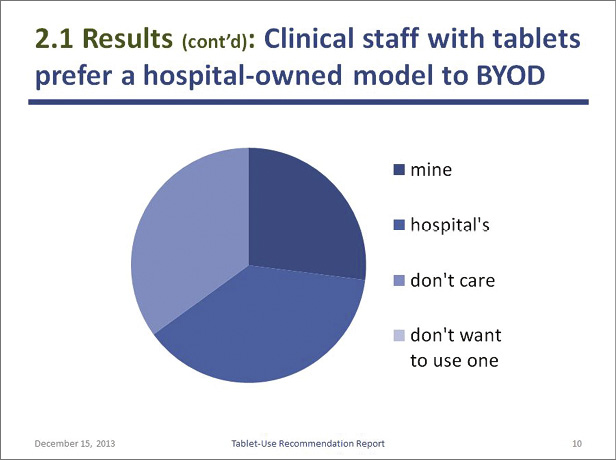

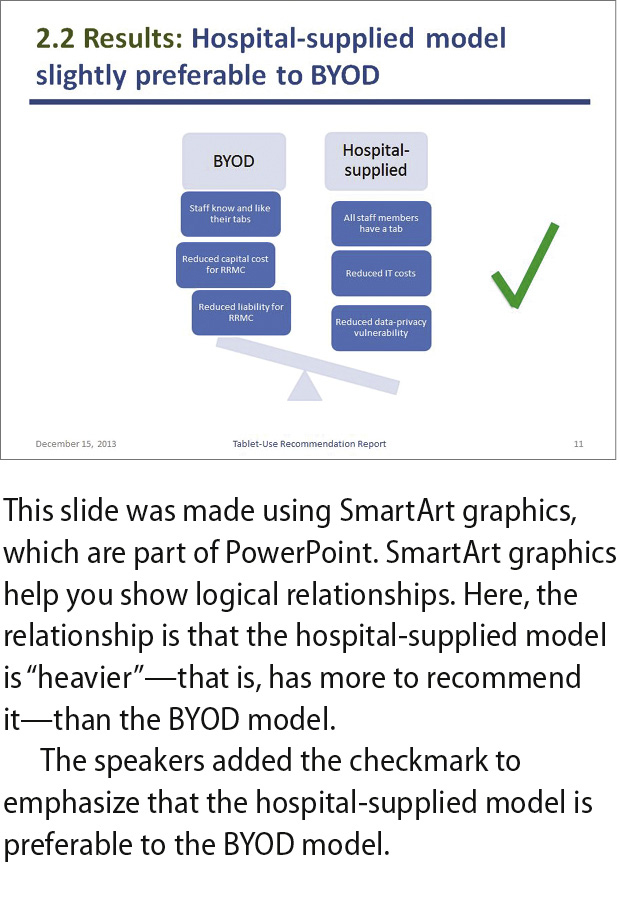

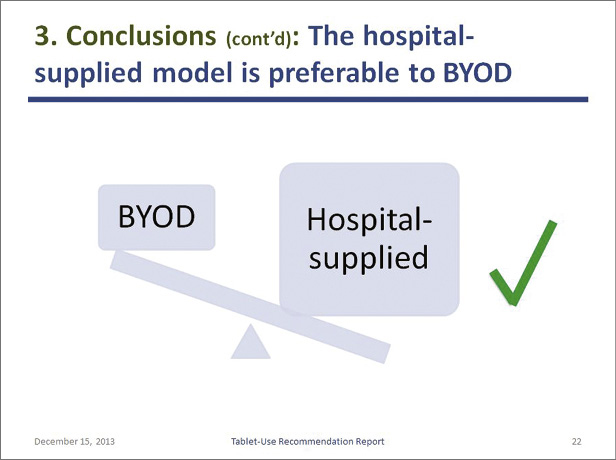

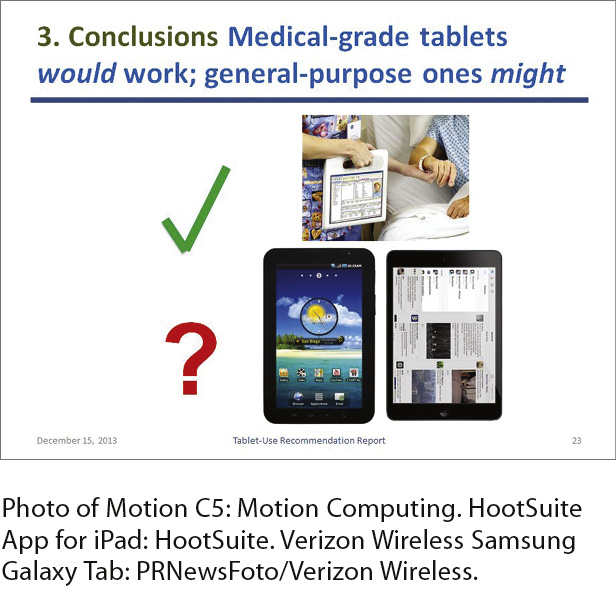

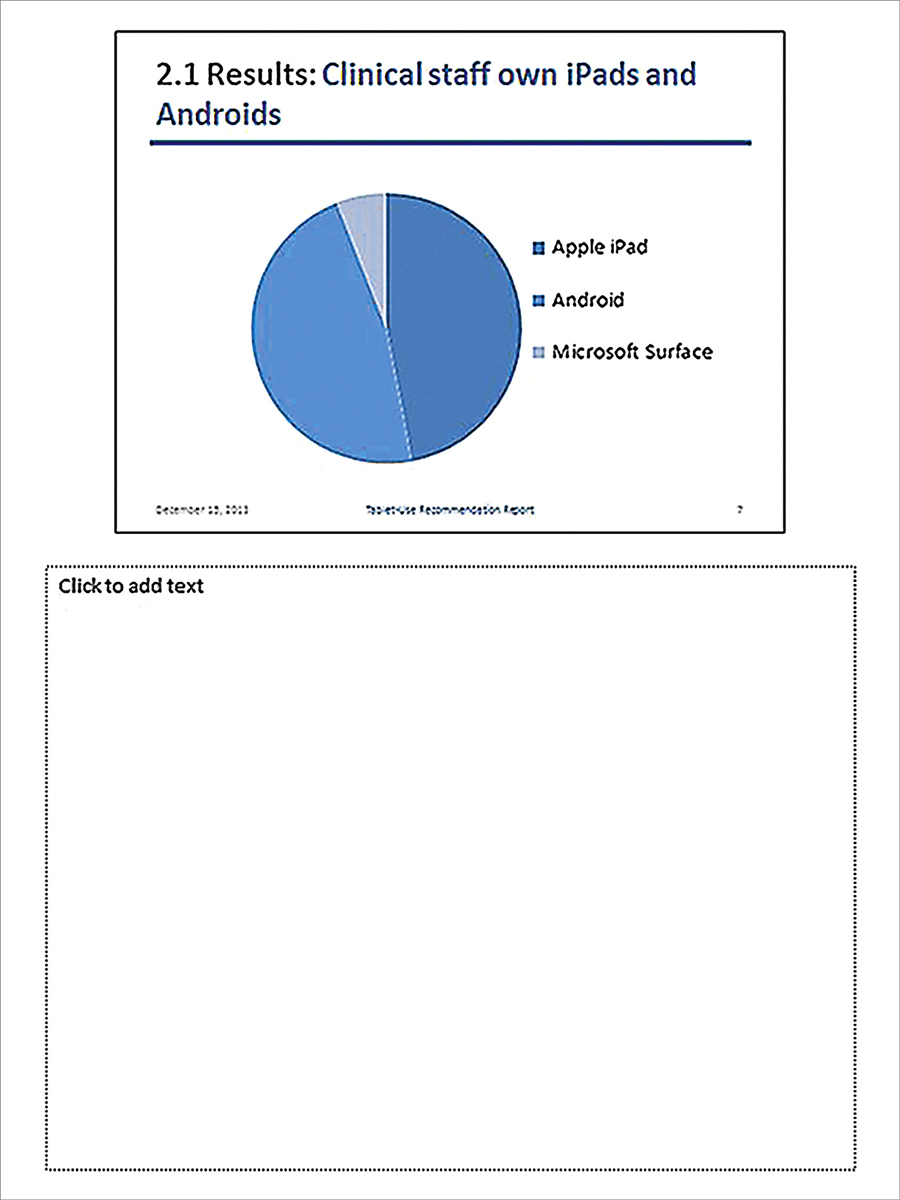

Using Graphics To Signal the Organization of a Presentation Used effectively, graphics can help you communicate how your presentation is organized. For example, you can use the transition from one graphic to the next to indicate the transition from one point to the next. Figure 15.3 shows the slides for a presentation that accompanied the report in Chapter 13 on tablet computer use at Rawlings Regional Medical Center.

Click on each slide to view it at a larger size.

Figure 15.3 Sample PowerPoint Presentation

Presentation software allows you to create two other kinds of documents—

CHOOSING EFFECTIVE LANGUAGE

Delivering an oral presentation is more challenging than writing a document because listeners can’t reread something they didn’t understand. In addition, because you are speaking live, you must maintain your listeners’ attention, even if they are hungry or tired or the room is too hot. Using language effectively helps you meet these two challenges.

Even if you use graphics effectively, listeners cannot “see” the organization of a presentation as well as readers can. For this reason, use language to alert your listeners to advance organizers, summaries, and transitions.

Advance organizers. Use an advance organizer (a statement that tells the listener what you are about to say) in the introduction. In addition, use advance organizers when you introduce main ideas in the body of the presentation.

Summaries. The major summary is in the conclusion, but you might also summarize at strategic points in the body of the presentation. For instance, after a three-

to four- minute discussion of a major point, you might summarize it in one sentence before going on to the next major point. Here is a sample summary from a conclusion: Page 442Let me conclude by summarizing my three main points about the implications of the new RCRA regulations on the long-

range waste- management strategy for Radnor Township. The first point is . . . . The second point is . . . . The third point is . . . . I hope this presentation will give you some ideas as you think about the challenges of implementing the RCRA. Transitions. As you move from one point to the next, signal the transition clearly. Summarize the previous point, and then announce that you are moving to the next point:

It is clear, then, that the federal government has issued regulations without indicating how it expects county governments to comply with them. I’d like to turn now to my second main point. . . .

To maintain your listener’s attention, use memorable language. A note about humor: only a few hundred people in the United States make a good living being funny. Don’t plan to tell a joke. If something happens during the presentation that provides an opening for a witty remark and you are good at making witty remarks, fine. But don’t prepare to be funny.

Using Memorable Language in Oral Presentations

Draw on these three techniques to help make a lasting impression on your audience.

Involve the audience. People are more interested in their own concerns than in yours. Talk to the audience about their problems and their solutions. In the introduction, establish a link between your topic and the audience’s interests. For instance, a presentation to a city council about waste management might begin like this:

Picture yourself on the Radnor Township Council two years from now. After exhaustive hearings, proposals, and feasibility studies, you still don’t have a waste-

management plan that meets federal regulations. What you do have is a mounting debt: the township is being fined $1,000 per day until you implement an acceptable plan. Refer to people, not to abstractions. People remember specifics; they forget abstractions. To make a point memorable, describe it in human terms:

What could you do with that $365,000 every year? In each computer lab in each school in the township, you could replace each laptop every three years instead of every four years. Or you could expand your school-

lunch program to feed every needy child in the township. Or you could extend your after- school programs to cover an additional 3,000 students. Use interesting facts, figures, and quotations. Search the Internet for interesting information about your subject. For instance, you might find a brief quotation from an authoritative figure in the field or a famous person not generally associated with the field (for example, Theodore Roosevelt on waste management and the environment).

REHEARSING THE PRESENTATION

Even the most gifted speakers need to rehearse. It is a good idea to set aside enough time to rehearse your speech thoroughly.

First rehearsal. Don’t worry about posture or voice projection. Just deliver your presentation aloud with your presentation slides. Your goal is to see if the speech makes sense—

if you can explain all the points and create effective transitions. If you have trouble, stop and try to figure out the problem. If you need more information, get it. If you need a better transition, create one. You are likely to learn that you need to revise the order of your slides. Pick up where you left off and continue the rehearsal, stopping again where necessary to revise. Second rehearsal. This time, the presentation should flow more easily. Make any necessary changes to the slides. When you have complete control over the organization and flow, check to see if you are within the time limit.

Third rehearsal. After a satisfactory second rehearsal, try the presentation under more realistic circumstances—

if possible, in front of others. The listeners might offer questions or constructive advice about your speaking style. If people aren’t available, record a video of the presentation on your computer or phone, and then evaluate your own delivery. If you can visit the site of the presentation to rehearse there, you will find giving the actual speech a little easier.

Rehearse again until you are satisfied with your presentation, but don’t try to memorize it.