7.2 Home

Can children thrive in every family? The answer is yes. The key lies in what parents do. We know that parents need to promote a secure attachment and be sensitive to a child’s temperamental needs. Is there an overall discipline style that works best? In landmark studies conducted 40 years ago, developmentalist Diana Baumrind (1971) decided yes.

Parenting Styles

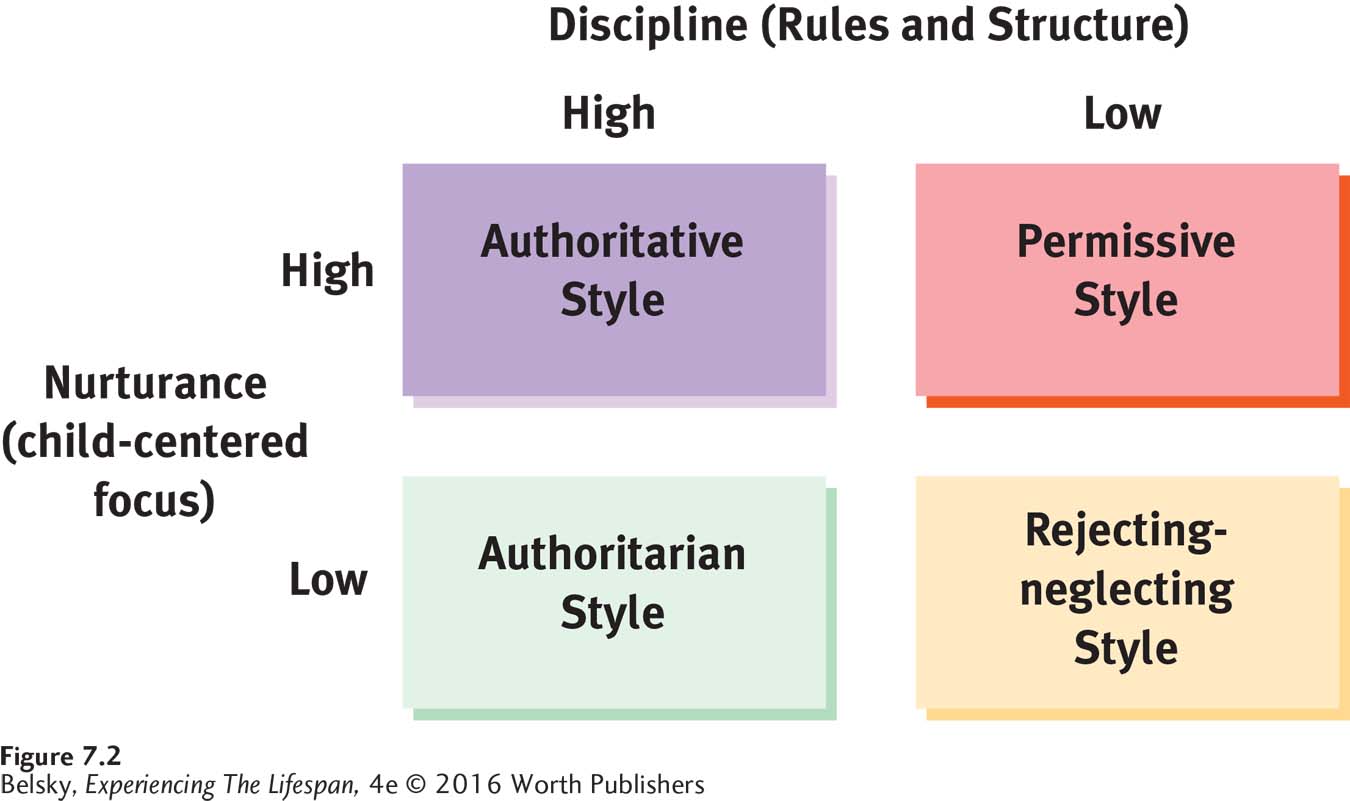

Think of a parent you admire. What is that mother or father doing right? Now think of parents who you feel are not fulfilling this job. Where are they falling short? Most likely, your list will center on two functions. Are these people nurturing? Do they provide discipline or rules? By classifying parents on these two dimensions—

Authoritative parents rank high on nurturing and setting limits. They set clear standards for their children but also provide some freedom and lots of love. In this house, there are specific bed and homework times. However, if a daughter wants to watch a favorite TV program, these parents might relax the rule that homework must be finished before dinner. They could let a son extend his regular 9:00 p.m. bedtime for a special event. Although authoritative parents believe in structure, they understand that rules don’t take precedence over human needs.

Figure 7.2: Parenting styles: A summary diagram.Source: Adapted from Baumrind, 1971.

Figure 7.2: Parenting styles: A summary diagram.Source: Adapted from Baumrind, 1971.Authoritarian parents are more inflexible. Their child-

rearing motto is, “Do just what I say.” In these families, rules are not negotiable. While authoritarian parents may love their children deeply, their child- rearing style can seem inflexible, rigid, and cold. Permissive parents are at the opposite end of the spectrum from authoritarian parents. Their parenting mantra is, “Provide total freedom and unconditional love.” In these households, there may be no set bedtimes and no homework demands. The child-

rearing principle here is that children’s wishes rule. Rejecting-

neglecting parents are the worst of both worlds—low on structure and on love. In these families, children are neglected, ignored, and emotionally abandoned. They are left to raise themselves (see Figure 7.2 for a recap).

In relating the first three discipline studies to children’s behavior (the fourth was added later), Baumrind found that children with authoritative parents were more successful and socially skilled. Hundreds of twentieth-

Decoding Parenting in a Deeper Way

At first glance, Baumrind’s authoritative category offers a beautiful blueprint for the right way to raise children: Provide structure and lots of love. However, if you classify your parents along these dimensions, you may find problems. Perhaps one parent was permissive and another authoritarian. Or, your families’ rules might randomly vary from authoritative to permissive over time.

According to one global study, the worst situation—

But aren’t there times when parenting styles should vary, or situations when every child needs a more authoritarian or permissive approach? These questions bring me to two other classic parenting styles critiques:

CRITIQUE 1: PARENTING STYLES VARY FROM CHILD TO CHILD AND MAY SHIFT AT DIFFERENT LIFE STAGES. Perhaps your parents came down harder on a brother or sister because that sibling needed more discipline, while your personality flourished with a permissive style. As you learned earlier in this book, good parents should vary their child-

Unfortunately, however, as you also learned in previous chapters, when children are “high maintenance” (difficult to raise), due to an evocative process, parenting styles are apt to change for the worse. A mom may become excessively controlling (authoritarian) when her child has a chronic illness (Pinquart, 2013). She might yell, scream, and wall herself off emotionally from a son or daughter with ADHD (Gau & Chang, 2013).

A study conducted in Finland suggested mothers were most likely to retreat into walled-

So again, parenting is far more “bidirectional” (and child evoked) than Baumrind assumes. Moreover, parents are apt to become less loving in the very situations when children need extra loving the most. Does adopting a rule-

CRITIQUE 2: PARENTING STYLES CAN VARY DEPENDING ON ONE’S SOCIETY. Baumrind’s styles perspective, developmentalists point out, reflects a Western middle-

This cultural difference, specifically in Asian parenting, was spelled out in a controversial book called The Battle Hymn of The Tiger Mother (2011). Amy Chua, a second-

Do Asian-

Should Western parents adopt Chua’s rule-

In the past, parents needed to act authoritarian to socialize their children for life in harsh, dictatorial societies or protect their offspring from the horrors of war or disease. In dangerous places today, such as El Salvador, people still report reluctantly using these rigid child-

INTERVENTIONS: Lessons for Thinking About Parents

How can you use these insights to think about parents in a more empathic way?

Understand that parenting styles don’t operate in a vacuum. They vary depending on a family’s unique life situation and a unique child.

Understand that retreating emotionally is normal when dealing with a child who has problems, but realize that in our culture, adopting this distant, authoritarian style signals parenting distress.

Rather than accusing parents of being “soft” or permissive, celebrate the fact that today we can be child-

centered, in the sense of listening empathically to our daughters and sons. Without minimizing the need for consistent rules, ideal twenty- first- century parenting boils down to three joyous principles: “Listen, nurture, offer lots of love!”

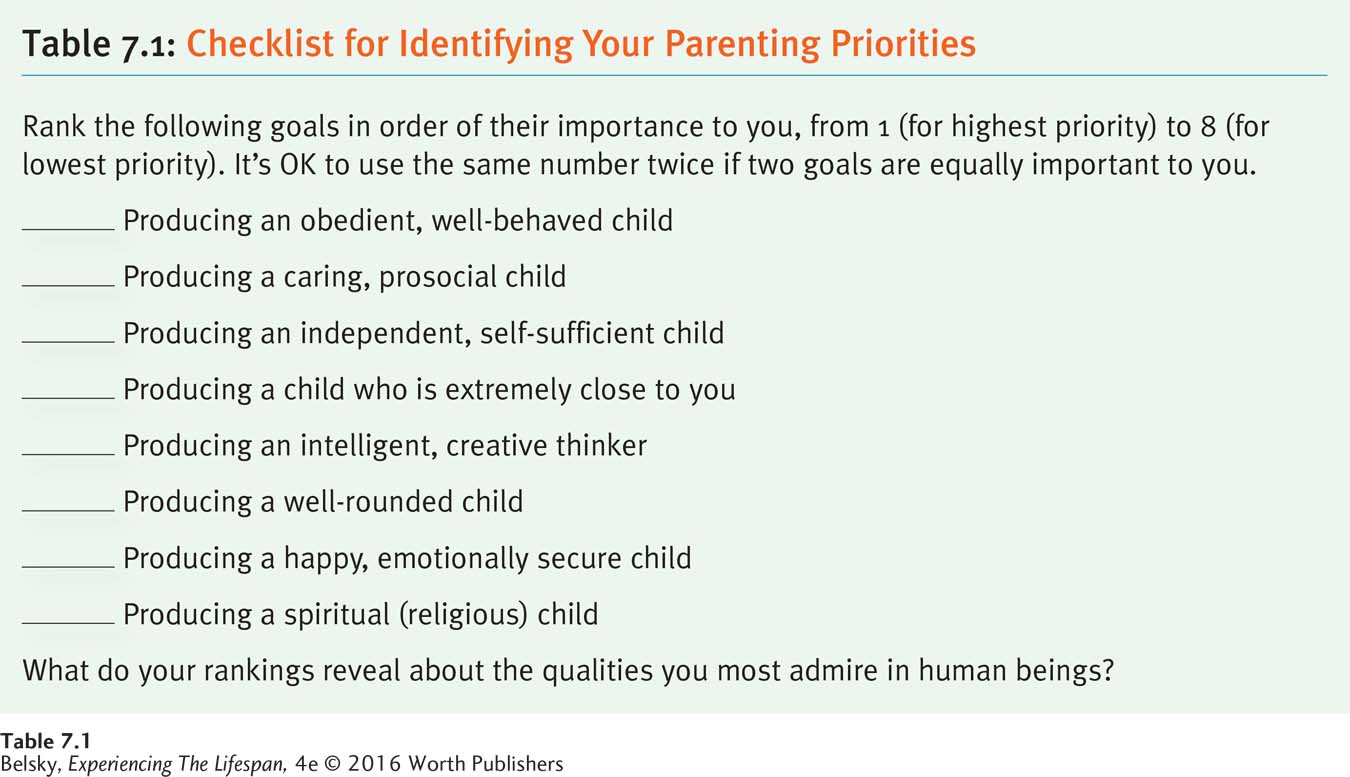

Table 7.1 gives you a chance to step back and list your specific parenting priorities in a deeper way. Let’s now consider that deeper philosophical question: Is parenting critically important to how children turn out?

How Much Do Parents Matter?

The most inspiring place to start is with those world-

Hot in Developmental Science: Resilient Children

His aristocratic parents spent their time gallivanting around Europe; they never appeared at the nursery doors. At age 7, he was wrenched from the only person who loved him—

Churchill’s upbringing was a recipe for disaster. He had neglectful parents, behavior problems, and was a failure at school. But this dismal childhood produced the leader who saved the modern world.

Resilient children, like Churchill, confront terrible conditions such as parental abuse, poverty, and war and go on to construct successful, loving lives. What qualities allow these unusual children to thrive?

Developmentalists find that resilient children often have a special talent, such as Churchill’s gift for writing, or superior cognitive skills. They are skilled at regulating their emotions. They have a high sense of self-

Being resilient depends on inner resources—

Not only is the quantity of life stress important, so are “social supports.” Children who succeed against incredible odds typically have at least one close, caring relationship with a parent or another adult (such as Churchill’s nanny). Like a plant that thrives in the desert, resilient children have the internal resources to extract love from their parched environment. But they cannot survive without any water at all.

Might these children have resilience-

Making the Case That Parents Don’t Matter

What matters more in how we develop, our life experiences or our genes? Twin and adoption studies, as I mentioned in Chapter 1, come down firmly on the “it’s mainly genetic” side. Faced with this nature-

The most interesting twist on this “parents don’t matter” argument was put forth by psychologist Judith Harris. Harris (1995, 1998, 2002, 2006) believes that the environment has a dramatic impact on our development; but—

Harris begins by taking aim at the principle underlying attachment theory—

Any parent can relate to Harris’s peer-

The most compelling evidence for Harris’s theory, however, comes from looking at immigrants. As I implied in the introductory chapter vignette, acculturation—children’s rapid shift to embrace new cultures—

These arguments that genetics and our culture shape development alert us to the fact that, when you see children “acting out,” you cannot leap to the assumption that “it’s the parents’ fault.” As developmental systems theory predicts, a variety of influences—

Many experts agree. For children to realize their genetic potential, parents should provide the best possible environment (Ceci and others, 1997; Kagan, 1998; Maccoby, 2002). In fact, when children are vulnerable or fragile as I’ve been pointing out, superior parenting is required.

Making the Case for Superior Parenting

Imagine, for instance, that your daughter is temperamentally “difficult.” You know from reading this book that you may be tempted to disengage emotionally from your child. You also know that adopting this less-

Actually, when a child is biologically fragile, or genetically reactive, sensitive caregiving can make a critical difference. From studies showing that loving touch helps premature infants grow (recall Chapter 3), to my suggestions for raising fearful or exuberant kids (see Chapters 4 and 6), the message is the same: When children are “at risk,” superior parenting matters most.

So let’s celebrate the fact that resilient children can flower in the face of difficult life conditions and less-

INTERVENTIONS: Lessons for Readers Who Are Parents

Now let’s summarize our discussion by talking directly to the parent readers of this book:

There are no firm guidelines about how to be an effective parent—

Try to see this message as liberating. Children cannot be massaged into having an idealized adult life. Your child’s future does not totally depend on you. Focus on the quality of your relationship, and enjoy these wonderful years. And if your son or daughter is having difficulties, draw inspiration from Winston Churchill’s history. Predictions from childhood to adult life can be hazy. Your unsuccessful child may grow up to save the world!

Now that I’ve covered the general territory, let’s turn to specifics. First, we’ll examine that controversial practice, spanking; then, focus on the worst type of parenting, child abuse; and finally, we’ll explore that common transition, divorce.

Spanking

Poll friends and family about corporal punishment—any discipline technique using physical measures such as spanking—

Until the twentieth century, corporal punishment used to be standard practice. Flogging was routine in prisons (Gould & Pate, 2010), the military, and other places (Pinker, 2011). In the United States, it was legal for men to “physically chastise” their wives (Knox, 2010). Today, while these practices still occur in less developed nations, in Western democracies they are widely condemned (Knox, 2010).

Moreover in recent years—

In the United States, we’ve been listening—

Still, with surveys showing only one in ten parents saying they “often spank,” corporal punishment is not the preferred U.S. discipline mode. Today, the most frequent punishments parents report are “time-

Who in Western nations is most likely to spank? Corporal punishment is widely accepted in the African American community (Burchinal, Skinner, & Reznick, 2010; Lorber, O’Leary, & Smith Slep, 2011). As one Black woman reported: “I would rather me discipline them than (the police)” (Taylor, Hamvas, & Paris, 2011, p. 65). As you might imagine from the “spare the rod, spoil the child” injunction, people who believe the Bible is literally true are most apt to strongly advocate this disciplinary technique (Rodriguez & Henderson, 2010).

Adults who were spanked as children see more value in this child-

What do experts advise? Here, there is debate. Many psychologists argue that physical punishment is never appropriate (Gershoff, 2002; Knox, 2010). They believe that hitting a child conveys the message that it is acceptable for big people to give small people pain. Yes, spanking, these psychologists point out, does produce compliance. But, it impairs prosocial behavior because it gets children to only focus on themselves (Andero & Stewart, 2002; Benjet & Kazdin, 2003; Knox, 2010).

Other experts believe that mild spanking is not detrimental (Baumrind, Larzelere, & Cowan, 2002; Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005; Oas, 2010). They suggest that, if we rule out corporal punishment, caregivers may resort to more damaging, shaming responses such as saying, “I hate you. You will never amount to anything.” But these psychologists have clear limits as to how and when this type of discipline might be used:

Never hit an infant. Babies can’t control their behavior. They don’t know what they are doing wrong. For a preschooler, a few light swats on the bottom can be a last resort disciplinary technique if a child is engaging in dangerous activities—

such as running into the street— that need to be immediately stopped (Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005). Page 207This action, however, must be accompanied by a verbal explanation (“What you did was wrong because . . .”) Spanking should rarely be considered only as a last ditch backup when other strategies, such as time-

outs, fail.

The problem is that spanking is often not a final backup—

Frequent spanking promotes the very behavior it is supposed to cure. To take one example, researchers found that parents who believed strongly in spanking had kids who said it was fine, during disagreements with a playmate, to “hit” that other child (Simons & Wurtele, 2010). Worse yet, what might start out as a spanking can escalate as a parent “gets into it,” the child cries more, and soon you have that worst-

Child Abuse

Child maltreatment—the term for acts that endanger children’s physical or emotional well-

Everyone can identify serious forms of maltreatment; but there is a gray zone as to what activities cross the line (Greenfield, 2010). Does every spanking that leaves bruises qualify as physical abuse? If a single mother leaves her toddler in an 8-

This labeling issue partly explains why maltreatment statistics vary, depending on who we ask. In one global summary (involving an amazing 150 studies and 10 million participants), scientists estimated that roughly 3 of 1,000 children worldwide were physically maltreated, using informant’s (meaning, other people’s) reports. In polling adults themselves, the rates were 10 times higher than that (Stoltenborgh and others, 2013). Considering all forms of abuse, the figures are alarming: 15 percent of teenage boys were labeled as abused in a city in Iran (Mikaeili, Barahmand, & Abdi, 2013). In Canada, 1 in 4 adults reported being maltreated as a child (MacMillan and others, 2013).

Obviously, far more individuals will report (“I was abused”), than the “objective” abuse-

What we can say is that, while a few adults are prone to err in the over-

Exploring the Risk Factors

As developmental systems theory would predict, several categories of influence cause child abuse to flare up (Wolfe, 2011):

PARENTS’ PERSONALITY PROBLEMS ARE IMPORTANT. People who abuse their children tend to suffer from psychological disorders such as depression and externalizing problems (Annerbäck, Svedin, & Gustafsson, 2010). They often have hostile attributional biases (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011; Crouch and others, 2010), assuming “bad” behavior from benign activities, like a toddler’s running around. Their determination not to “spoil” their babies is accompanied by other unrealistic expectations. They may believe that 3-

LIFE STRESS ACCOMPANIED BY SOCIAL ISOLATION CAN BE CRUCIAL. Abusive parents are often young and poorly educated (Bartlett & Easterbrooks, 2012; Sieswerda-

CHILDREN’S VULNERABILITIES PLAY A ROLE. A child who is emotionally fragile can fan this fire—

Exploring the Consequences

As you learned in Chapter 4, maltreated children often have insecure attachments (Stronach and others, 2011). They tend to suffer from internalizing and externalizing problems (Mills and others, 2013), and get rejected by their peers (Kim & Cicchetti, 2010). Just as with the orphanage-

Because terrible childhood experiences prime us epigenetically to biologically break down (Shapero and others, 2014), it comes as no surprise that the long-

Still most abused children become decent, caring parents (Woodruff and Lee, 2011). Some are passionate to never, ever hit their daughters and sons (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011). As one woman described: “I made a vow to protect my children no matter what. . . . It was almost like a mantra, that I’m never going to strike (my child)” (quoted in Hall, 2011, p. 38).

People who break the cycle of abuse tend to have good intellectual and coping skills (Hengartner and others, 2013). They are blessed to have a DNA profile that I alluded to earlier, that makes them genetically more resistant to stress (Banducci and others, 2014). Being blessed to have a stable, loving marriage also offers potent insulation from repeating the trauma of abuse (Jaffe and others, 2013).

INTERVENTIONS: Taking Action Against Child Abuse

What should you do if you suspect child abuse? The law requires teachers, social workers, health-

Unfortunately, there are powerful temptations not to speak up. If you make a false report, you risk ruining a family’s life. You may feel that you don’t have the training to make a difficult judgment call, or fear your life would be in danger from a vengeful parent if you made a report (see Chen and others, 2010; Osofsky and Lieberman, 2010): “Are those injuries normal accidents, or are the patterned bruises characteristic of being hit by a cord or belt?” (Harris, 2010.) “If I do report the situation, will authorities take any action?”

This last fear seems justified. In one Swedish study, even in the face of accusations of severe abuse, only about 10 percent of children were physically examined. Roughly 1 percent of the cases actually went to trial (Otterman, Lainpelto, & Lindblad, 2013). This is unfortunate, because with abuse, the family situation can get worse. In one study tracking U.S. families with documented histories of maltreatment, the home environment deteriorated from preschool to kindergarten, with mothers doing more yelling and having fewer caring interactions, especially with sons (Haskett, Neupert, & Okado, 2014).

Divorce

Although developed-

Let’s start with the bad news. Studies comparing children of divorce with their counterparts in intact married families show that these boys and girls are at a disadvantage—

The good news is that most children cope with divorce very well, especially if this family event is fairly drama free. Still, I don’t want to minimize the guilt parents feel when making this choice. One woman in a Finnish study revealed these predictable feelings when she anguished: “What am I to change two close people’s lives . . . Was a thought that did not leave me for a long time” (as reported in Kiiski & Määttä Uusiautti, 2013).

Imagine coping with feeling you have failed your family and then needing to have a conversation that upends your children’s world. And it’s not just that you explain, “Mommy and Daddy need to live apart, but we still love you,” and children get over the news. One Israeli woman described a fairly common scenario when she reported that for months her daughter’s conversations started with the phrase, “Soon, when Dad will come back home” (quoted in Cohen, Leichtentritt, & Volpin, 2014).

In this interview study exploring the feelings of newly divorced Israeli mothers, women said their main agenda was to minimize their children’s pain. So, they struggled to put aside their vengeful feelings and not bad-

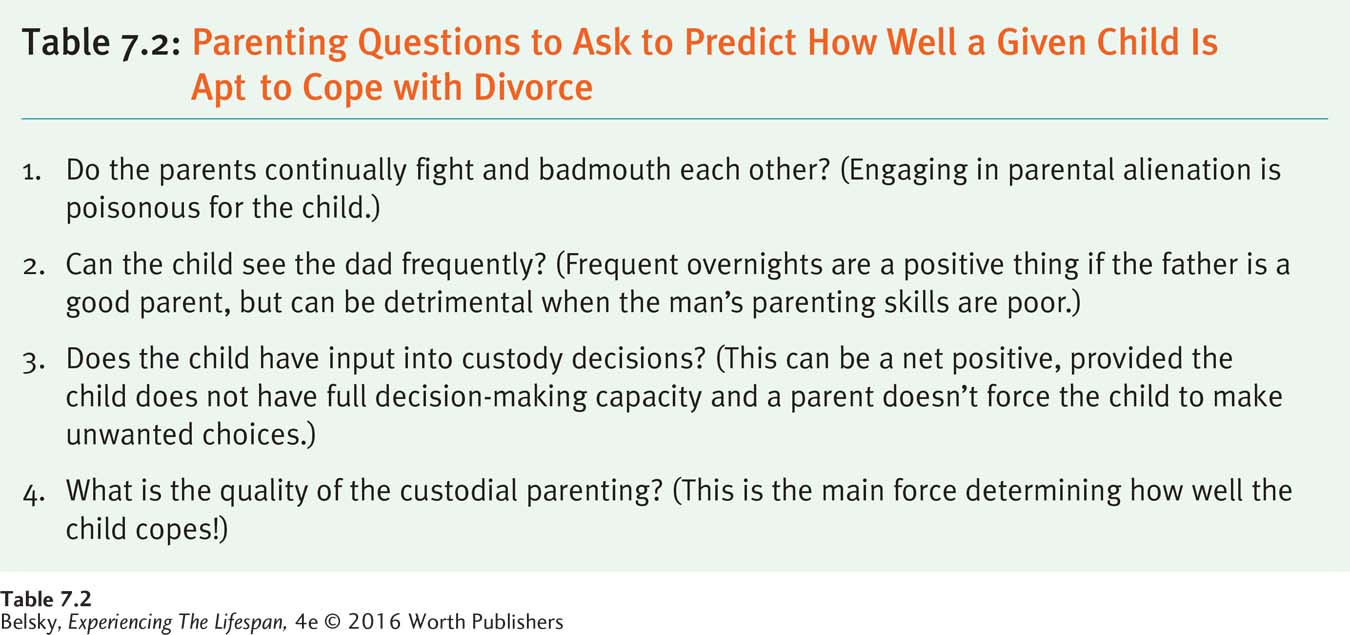

This is not to say that parental alienation—poisoning children against ex-

The compelling lure to succumb to relational aggression (that is, enlisting children against a former spouse) brings up the subject of custody and visitation. When the divorce is bitter (or high conflict) should a child be allowed to frequently see both the dad and mom?

For almost the entire twentieth century, the mother was given custody unless there was a serious problem with her parenting (based on the psychoanalytic principle that women are inherently superior nurturers)—a practice that unfairly limited dads from being involved in their children’s lives. Today, Western nations—

Does this permeable visiting schedule help children cope? Actually, “it depends.” Researchers found that after a divorce, moving an infant child from house to house predicted greater attachment insecurity. In contrast, adolescent research suggested that teens who split their living arrangements between ex-

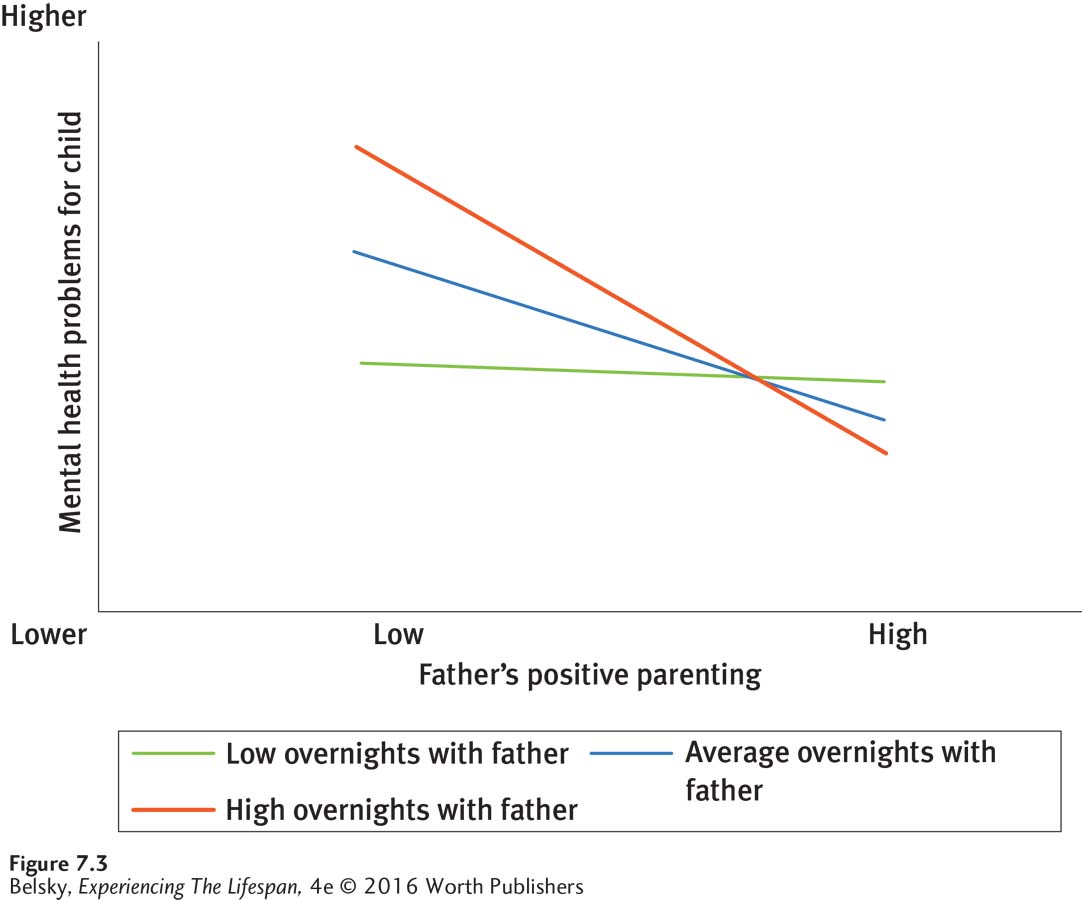

The most informative finding comes from scanning Figure 7.3. While more overnights with a dad who provides positive parenting promotes adjustment, if a father had poor parenting skills, children’s emotional problems escalated (Sandler, Wheeler, & Braver, 2013).

So with custody and visitation, we need to take an individual-

Should children be able to decide which custody and visitation arrangement they prefer? One experiment, comparing standard divorce mediation with approaches centered more on child wishes, suggested yes (Ballard and others, 2013).

Still, in a poll of divorced families, everyone recoiled at the idea of putting total decision-

At this point some of you might be thinking unhappy couples should try to bite the bullet and stay together for the sake of their children. If the marriage is labeled “high conflict,” think again. For children subjected to continual marital fighting, ending the marriage improves well-

Table 7.2 summarizes these points in a parenting-

Tying It All Together

Question 7.1

Montana’s parents make firm rules but value their children’s input about family decisions. Pablo’s parents have rules for everything and tolerate no ifs, ands, or buts. Sara’s parents don’t really have rules. At their house it’s always playtime and time to indulge the children. Which parenting style is being used by Montana’s parents? By Pablo’s parents? By Sara’s parents?

Montana’s parents = authoritative. Pablo’s parents = authoritarian. Sara’s parents = permissive.

Question 7.2

Chloe grew up in a happy middle-

Amber

Question 7.3

Melissa’s son Jared, now in elementary school, was premature and has a difficult temperament. What might Judith Harris advise about fostering this child’s development, and what might this chapter recommend?

Judith Harris’s advice = Get your son in the best possible peer group. This chapter’s recommendation = Provide exceptionally sensitive parenting.

Question 7.4

Your sister is concerned about a friend who uses corporal punishment with her baby and her 4-

Never spank children of any age.

Mild spanking is OK for the infant.

Mild spanking is OK for the 4-

year- old, as a backup. If the child has a difficult temperament, regular corporal punishment might help.

a and c

Question 7.5

Ms. Johnson, an elementary school teacher, is worried about a student who has been coming to school unwashed and with torn clothes. Yesterday, she saw what looked like burn marks on the child’s arms. Describe how Ms. Johnson might feel about reporting this situation, and what might happen if she formally accuses the parent of abuse or neglect.

Ms. Johnson might feel torn about reporting her observations, because she is afraid of parents retaliating or worried about making false accusations. Even if she does make a report, there is a good chance authorities will not investigate the situation.

Question 7.6

Imagine you are a family court judge deciding to award joint custody. In a phrase, explain your main criterion for awarding unlimited overnights with a particular divorced dad.

The main criterion for awarding joint custody—