9.2 The Mysterious Teenage Mind

Thoughtful and introspective, but impulsive, moody, and out of control; peer-

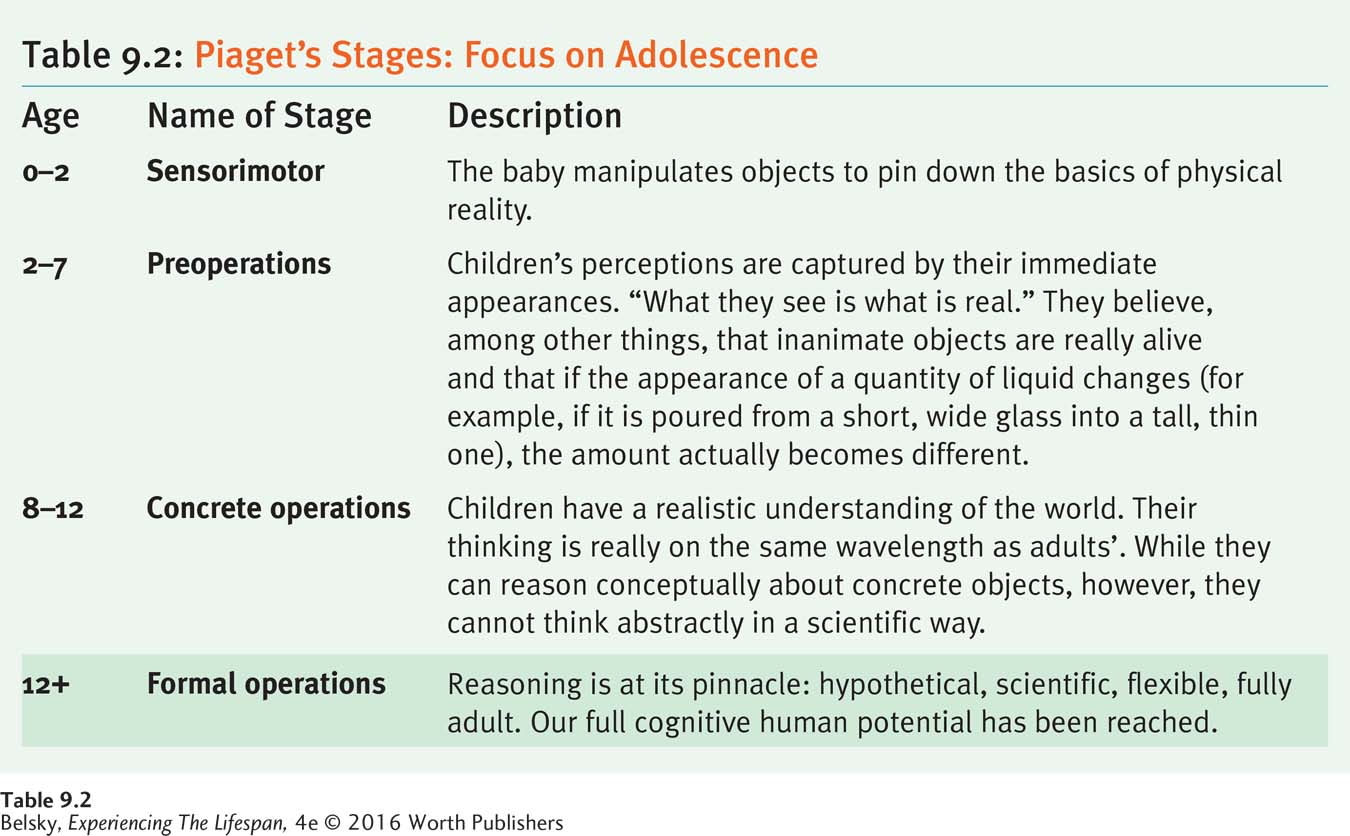

Three Classic Theories of Teenage Thinking

Have a thoughtful conversation with a 16-

Formal Operational Thinking: Abstract Reasoning at Its Peak

Children in concrete operations can look beyond the way objects immediately appear. They realize that when Mommy puts on a mask, she’s still Mommy “inside.” They understand that when you pour a glass of juice or milk into a different-

ADOLESCENTS CAN THINK LOGICALLY ABOUT CONCEPTS AND HYPOTHETICAL POSSIBILITIES. Ask fourth-

Moreover, if you give a child in concrete operations a reasoning task that begins, “Suppose snow is blue,” she will refuse to go further, saying, “That’s not true!” Adolescents in formal operations have no problem tackling that challenge because once our thinking is liberated from concrete objects, we are comfortable reasoning about concepts that may not be real.

ADOLESCENTS CAN THINK LIKE REAL SCIENTISTS. When our thinking occurs on an abstract plane, we can approach problems in a systematic way, devising a strategy to scientifically prove that something is true.

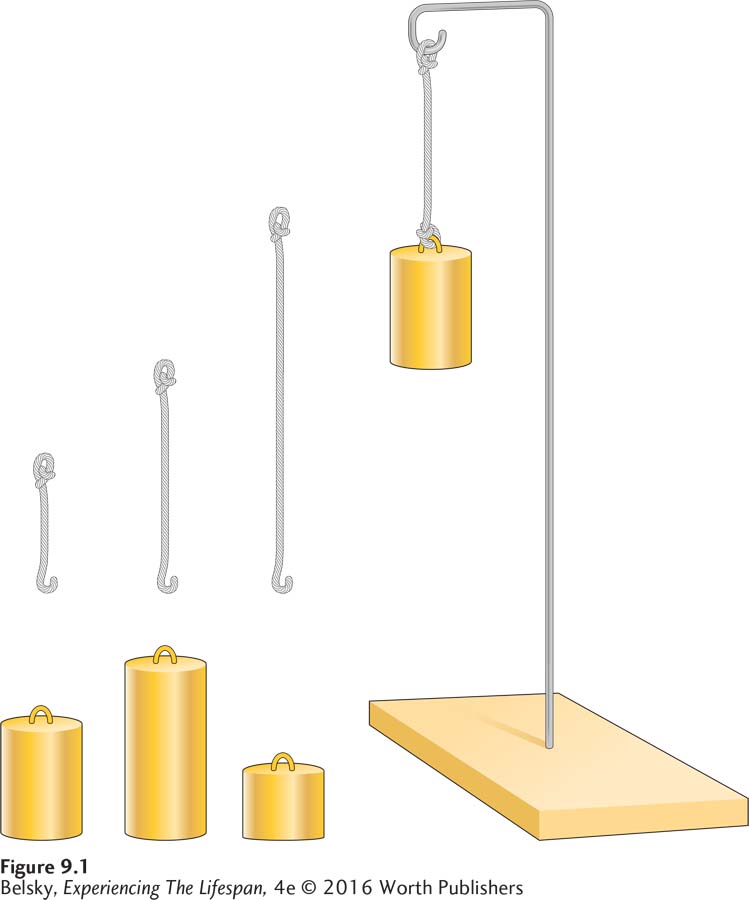

Piaget designed an exercise to reveal this new scientific thought: He presented children with a pendulum apparatus and unattached strings and weights (see Figure 9.1). Notice that the strings differ in their length and the weights vary in size or heaviness. Children’s task was to connect the weights to the strings, then attach them to the pendulum, to decide which influence determined how quickly the pendulum swung from side to side. Was it the length of the string, the heaviness of the weight, or the height from which the string was released?

Think about how to approach this problem, and you may realize that it’s crucial to be systematic—

Elementary school children, Piaget discovered, approach these problems haphazardly. Only adolescents adopt a scientific strategy to solve reasoning tasks (Flavell, 1963; Ginsburg & Opper, 1969).

HOW DOES THIS CHANGE IN THINKING APPLY TO REAL LIFE? This new ability to think hypothetically and scientifically explains why it’s not until in high school that we can thrill to a poetic metaphor or comprehend chemistry experiments (Kroger, 2000). It’s only during high school that we can join the debate team and argue the case for and against capital punishment, no matter what we personally believe. In fact, reaching the formal operational stage explains why teenagers are famous for debating everything in their lives. A 10-

But, do all adolescents reach formal operations? The answer is no. For one thing—

Still, even if many of us never reason like real scientists or master debaters, we can see the qualities involved in formal operational thinking if we look at how adolescents—

If you are a traditional emerging-

The bottom line is that reaching concrete operations allows us to be on the same wavelength as the adult world. Reaching formal operations allows us to act in the world like adults.

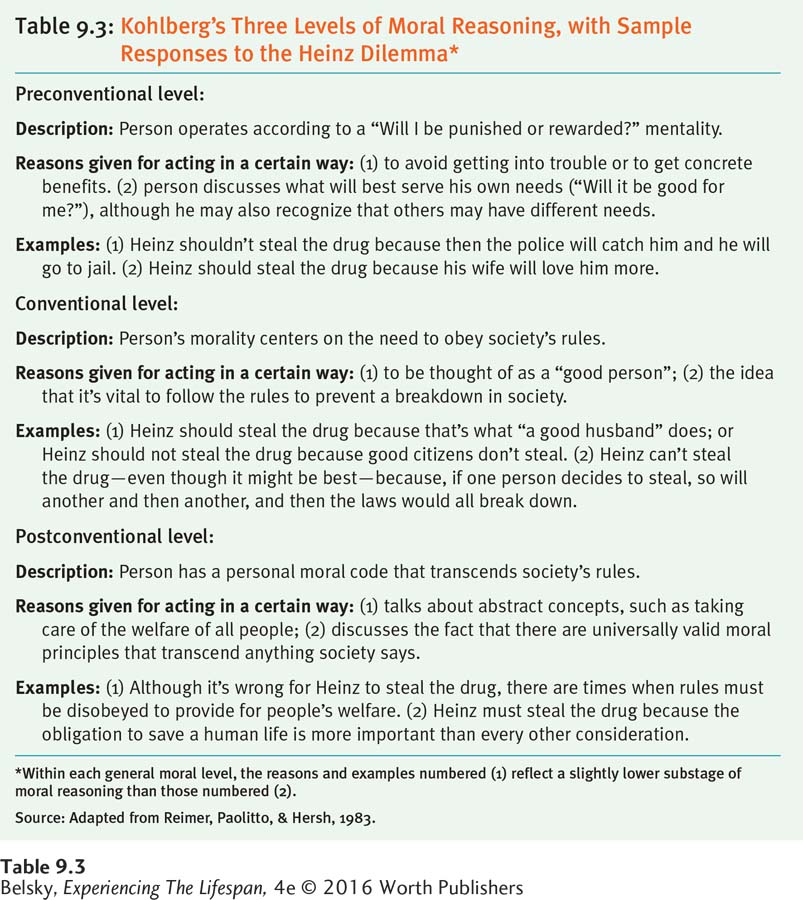

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Judgment: Developing Internalized Moral Values

This new ability to reflect on ourselves as people allows us to reflect on our personal values. Therefore, drawing on Piaget’s theory, developmentalist Lawrence Kohlberg (1981, 1984) argued that during adolescence we become capable of developing a moral code that guides our lives. To measure this moral code, Kohlberg constructed ethical dilemmas, had people reason about these scenarios, and asked raters to chart the responses according to the three levels of moral thought outlined in Table 9.3 on p. 264. Before looking at the table, take a minute to respond to the “Heinz dilemma,” the most famous problem on Kohlberg’s moral judgment test:

A woman was near death from cancer. One drug might save her. The druggist was charging . . . ten times what the drug cost him to make. The . . . husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money but he could only get together about half of what it cost. [He] asked the . . . druggist to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said NO! Heinz broke into the man’s store to steal the drug. . . . Should he have done that? Why?

If you thought in terms of whether Heinz would be personally punished or rewarded for his actions, you would be classified at the lowest level of morality, the preconventional level. Responses such as “Heinz should not take the drug because he will go to jail,” or “Heinz should take the drug because then his wife will treat him well,” suggest that—

If you made comments such as “Heinz should [or shouldn’t] steal the drug because it’s a person’s duty to obey the law [or to stick up for his wife]” or “Yes, human life is sacred, but the rules must be obeyed,” your response would be classified at the conventional level—right where adults typically are. This shows your morality revolves around the need to uphold society’s norms.

People who reason about this dilemma using their own moral guidelines apart from society’s rules are operating at Kohlberg’s highest postconventional level. A response showing postconventional reasoning might be, “No matter what society says, Heinz had to steal the drug because nothing outweighs the universal principle of saving a life.”

When he conducted studies with different age groups, Kohlberg discovered that at age 13, preconventional answers were universal. By 15 or 16, most children around the world were reasoning at the conventional level. Still, many of us stop right there. Although some of Kohlberg’s adults did think postconventionally, using his incredibly demanding criteria, almost no person consistently made it to the highest moral stage (Reimer, Paolitto, & Hersh, 1983; Snarey, 1985).

HOW DOES KOHLBERG’S THEORY APPLY TO REAL LIFE? Kohlberg’s categories get us to think deeply about our values. Do you have a moral code that guides your actions? Would you intervene, no matter what the costs, to save a person’s life? These categories give us insights into other people’s moral priorities, too. While reading about Kohlberg’s preconventional level, you might have thought: “I know someone just like this. This person has no ethics. He only cares about whether or not he gets caught!”

However, Kohlberg’s research has been severely criticized. For one thing, Kohlberg was wrong when he said that children can’t go beyond a punishment and reward mentality. Remember from Chapters 3 and 6, developmentalists now know that our basic sense of morality naturally kicks in at an incredibly young age.

In a classic late-

Gilligan’s criticisms bring up an interesting question: Is Kohberg’s scale valid? Does the way people reason about his scenarios relate to the attitudes and behaviors, which, as you learned in Chapter 6, predict acting prosocially in life? Unfortunately, the answer is “not necessarily.” When outstandingly prosocial teenagers—

Concerns about whether responses to artificial vignettes predict real-

Still, when he describes the changes in moral reasoning that take place during adolescence, Kohlberg has an important point. Teenagers are famous for questioning society’s rules, for seeing the injustice of the world, and for getting involved in idealistic causes. Unfortunately, this ability to step back and see the world as it should be, but rarely is, may produce the emotional storm and stress of teenage life.

Elkind’s Adolescent Egocentrism: Explaining Teenage Storms

This was David Elkind’s (1978) conclusion when he drew on Piaget’s concept of formal operations to make sense of teenagers’ emotional states. Elkind argues that, when children make the transition to formal operational thought at about age 12, they can see beneath the surface of adult rules. A sixth-

The realization that the emperor has no clothes (“Those godlike adults are no better than me”), according to Elkind, leads to anger, anxiety, and the impulse to rebel. From arguing with a ninth-

More tantalizing, Elkind draws on formal operational thinking to make sense of the classic behavior we often observe in young teens—

So 13-

A second component of adolescent egocentrism is the personal fable. Teenagers feel that they are invincible and that their own life experiences are unique. So Melody believes that no one has ever had so disgusting a blemish. She has the most embarrassing mother in the world.

These mental distortions explain the exaggerated emotional storms we laugh about during the early adolescent years. Unfortunately, the “It can’t happen to me” component of the personal fable may lead to tragic acts. Boys put their lives at risk by drag racing on the freeway because they imagine that they can never die. A girl does not use contraception when she has sex because, she reasons, “Yes, other girls can get pregnant, but not me. Plus, if I do get pregnant, I will be the center of attention, a real heroine.”

Studying Three Aspects of Storm and Stress

Are teenagers unusually sensitive to people’s reactions? Is Elkind (like other observers, from Aristotle to Shakespeare to G. Stanley Hall) correct in saying that risk taking is intrinsic to being a “hot-

Are Adolescents Exceptionally Socially Sensitive?

In the last chapter, you learned that, when they reach puberty, children—

Moreover, as Elkind would predict, when they reach puberty, children are especially sensitive to social disapproval. If presented with unfamiliar faces on a screen, and told they were unexpectedly rejected by those virtual peers, pre-

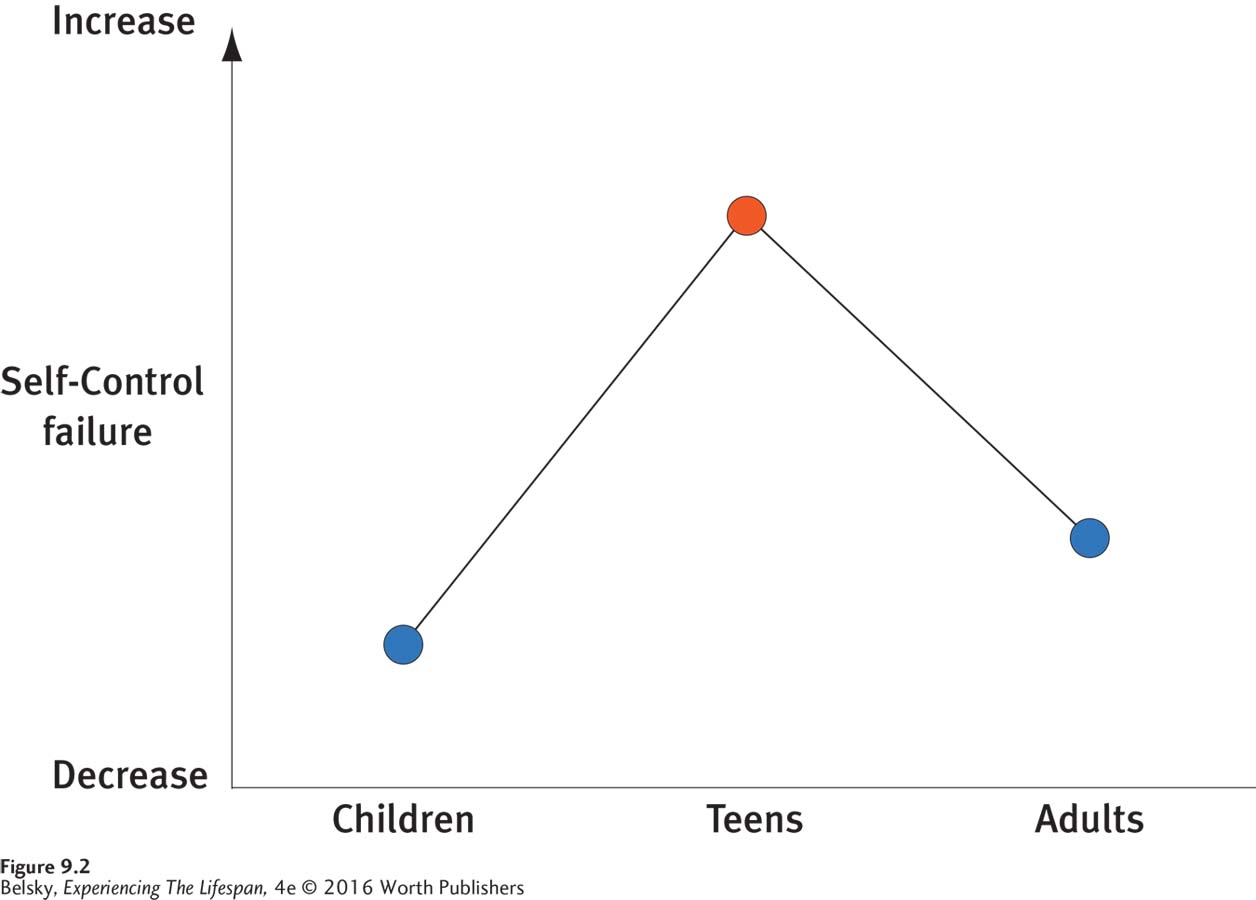

More telling, young teens are prone to act impulsively, specifically in situations involving arousing social cues (Blakemore & Mills, 2014). As Figure 9.2 reveals, they selectively fail Simon Says–

Moreover, fMRI studies show that this predisposition to act precipitously in emotional situations is mirrored in specific brain changes (Blakemore & Mills, 2014; Peake and others, 2013). So, the answer to the question, “Are adolescents more socially sensitive?” is “absolutely yes,” especially around the pubertal years!

HOW DO WE KNOW . . .

that adolescents make riskier decisions when they are with their peers?

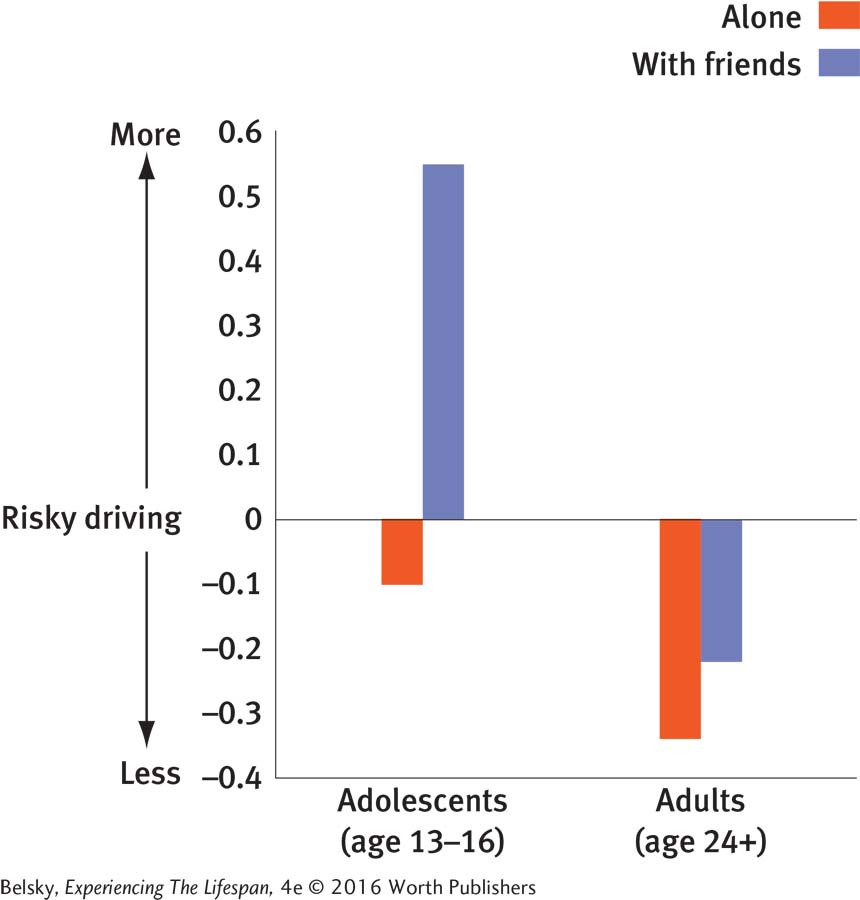

Their heightened social sensitivity gives us strong evidence that teenagers do more dangerous things in arousing situations with their friends. About a decade ago, an ingenious video study drove this point scientifically home. Researchers (Gardner & Steinberg, 2005) asked younger teenagers (aged 13 to 16), emerging adults (aged 18 to 22), and adults (aged 24-

The chart below shows the intriguingly different findings for young teenagers and for people over age 24. Notice that, while being with other people had no impact on risky decision making in the adults, it had an enormous effect on young teens, who were much more likely to risk crashing the car by driving farther after the yellow light appeared when with friends. The bottom line: Watch for risky behavior when groups of teenagers are together—

Are Adolescents Risk Takers?

Doing something and getting away with it. . . . You are driving at 80 miles an hour and stop at a stop sign and a cop will turn around the corner and you start giggling. Or you are out drinking or maybe you smoked a joint, and you say “hi” to a police officer and he walks by. . . .

(quoted in Lightfoot, 1997, p. 100)

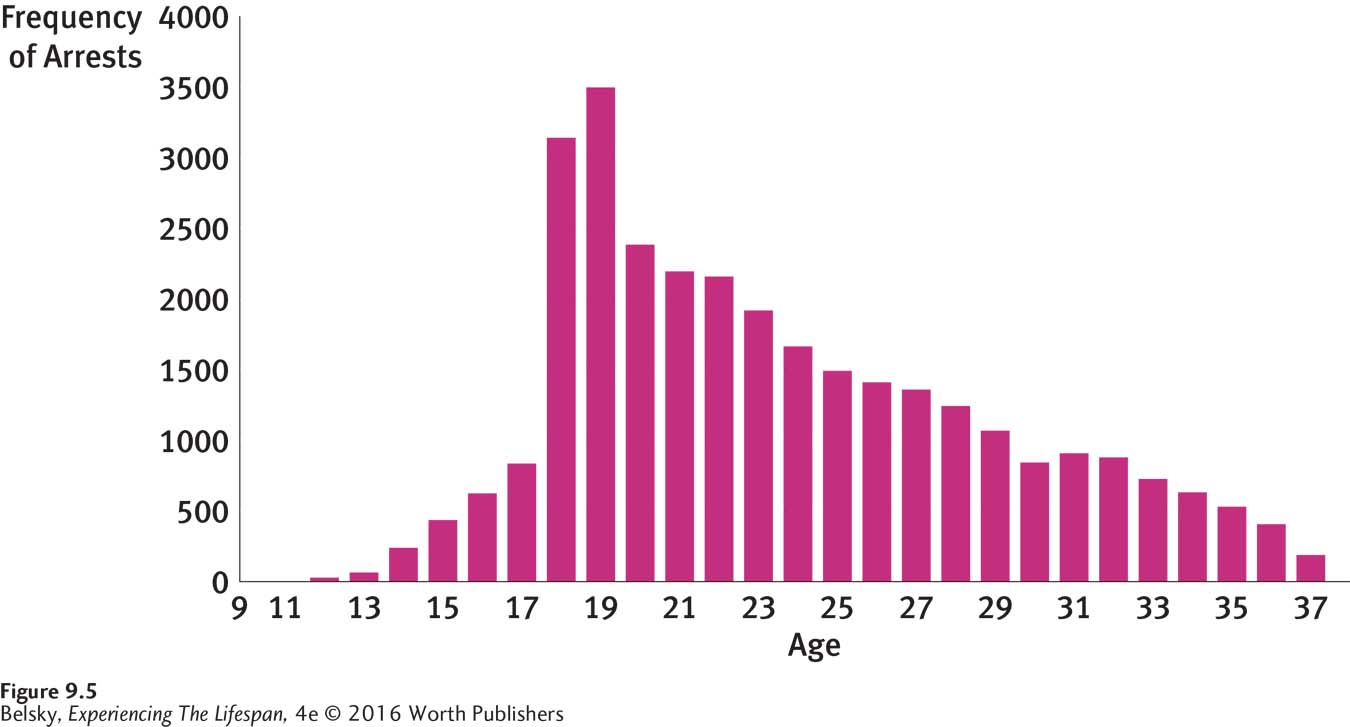

This quotation from a teen in an interview study, plus the research in the previous section, suggests that (no surprise) the second storm-

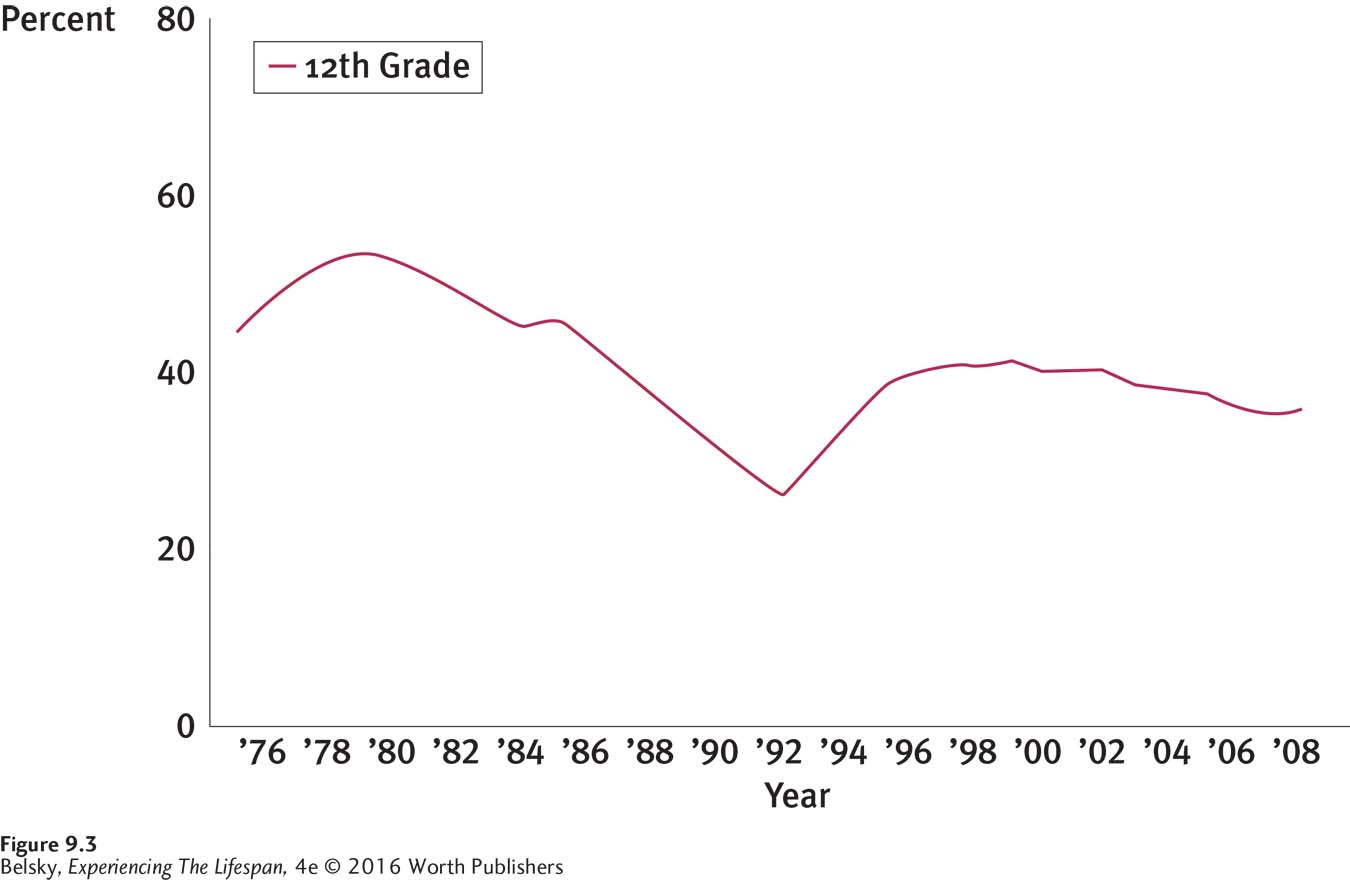

Consider, for instance, the findings of yearly nationwide University of Michigan–

The good news is that, as you can see in Figure 9.3, in contrast to our images of rampant teenage substance abuse, most high school seniors do not report using any drugs. The most recent 2013 University of Michigan poll found the lowest rates of teenage alcohol use since the survey was instituted four decades ago! (See Johnston and others, 2014.) The bad news is that—

Younger children also rebel, disobey, and test the limits. But, if you have seen a group of teenage boys hanging from the top of a speeding car, you know that the risks adolescents take can be threatening to life. At the very age when they are most physically robust, teenagers—

Are Adolescents More Emotional, More Emotionally Disturbed, or Both?

Given this information, it should come as no surprise that the third major storm-

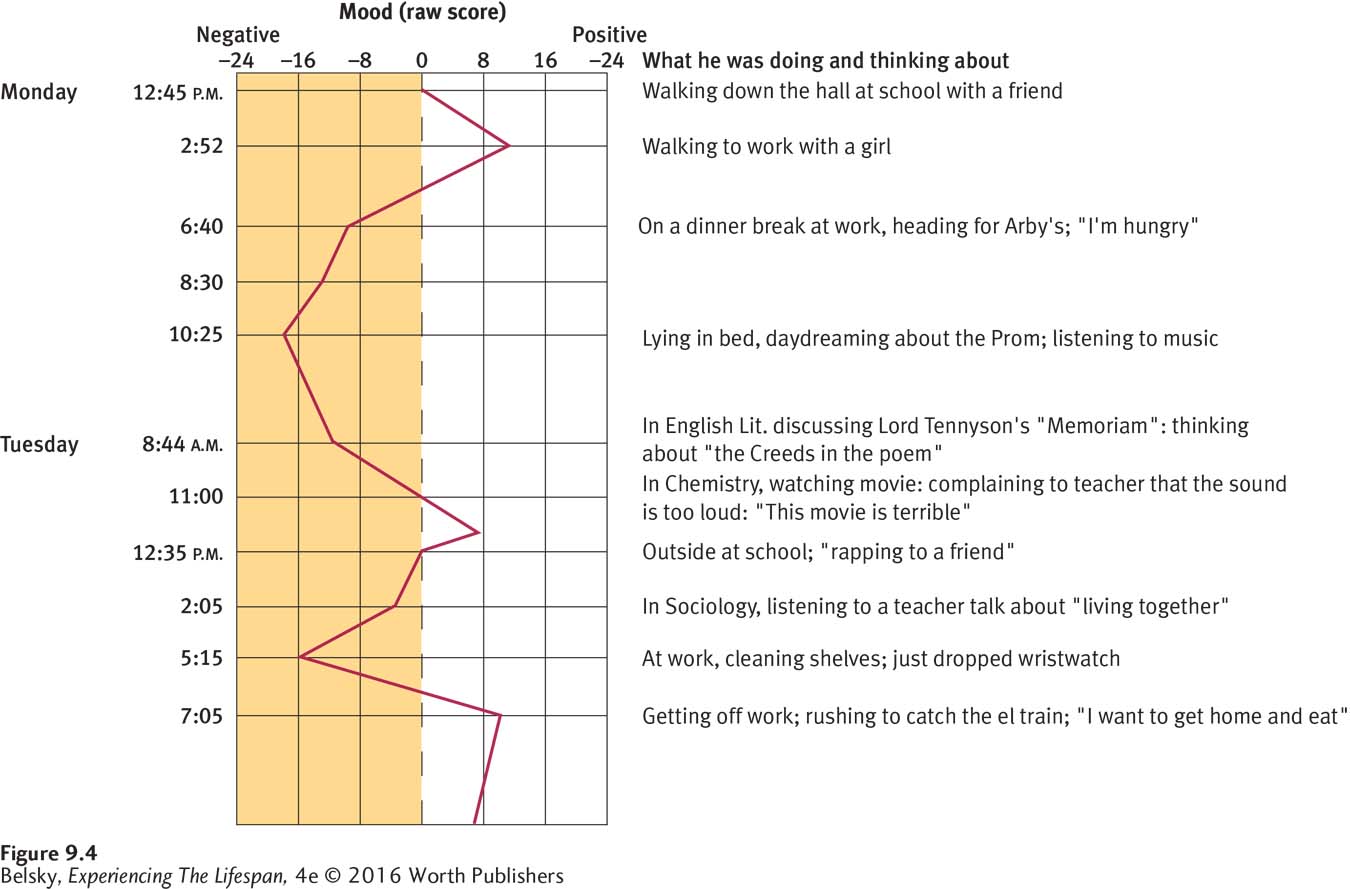

Imagine that you could get inside the head of a 16-

The records showed that adolescents do live life on an intense emotional plane. Teenagers reported experiencing euphoria and deep unhappiness far more often than a comparison sample of adults. Teenagers also had more roller-

Does this mean that adolescents’ moods are irrational? The researchers concluded that the answer was no. As Greg’s experience-

Does this mean that most adolescents are emotionally disturbed? Now, the answer is definitely no. Although the distinction can escape parents when their child wails, “I got a D on my chemistry test; I’ll kill myself!” there is a difference between being highly emotional and being emotionally disturbed.

Actually, when developmentalists ask teenagers to evaluate their lives, they get an upbeat picture of how young people generally feel. Most adolescents around the world are confident and hopeful about the future (Gilman and others, 2008; Lewin-

So the stereotypic impression that most teenagers are unhappy or suffer from serious psychological problems is false. Still, as you just read, the picture is far from totally rosy. Their risk-

Scientists are passionate to make sense of this global epidemic. The impulse to self-

Unfortunately, the answer is yes. Moreover, while the prevalence of this mental disorder is about equal for each sex during childhood, by the mid-

Depression rates may escalate during adolescence because the hormonal changes of puberty make the teenage brain more sensitive to stress (Romeo, 2013). But why is depression a mainly female disorder during adult life? Are women biologically primed to internalize their problems when under stress, and could this gender difference have roots in the womb? We do not know. What we do know is that if a child’s fate is to battle any serious mental health disorder, from depression to schizophrenia, that condition often has its onset in late adolescence or the early emerging-

Moreover, I believe that the push to be socially successful (or popular) may explain many classic distressing symptoms during the early teens.

Hot in Developmental Science: A Potential Pubertal Problem, Popularity

Young teens’ drive for social status, for instance, seems partly to blame for the fact that academic motivation often takes a nosedive in middle school (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2010; Li & Lerner, 2011). Worse yet—

Making it into the in crowd can also have personal costs. Pre-

Finally, because social standing is so important at this age (Molloy, Gest, & Rulison, 2011), getting isolated from the “in crowd” can lead to becoming depressed (Buck & Dix, 2012; Witvliet and others, 2010). Popularity pressures seem implicated in both the upsurge in unhappiness and acting out during the early teens!

Different Teenage Pathways

So far, I seem to be sliding into stereotyping “adolescents” as a monolithic group. This is absolutely not true! Teenagers, as we know, differ—

Which Teens Get into Serious Trouble?

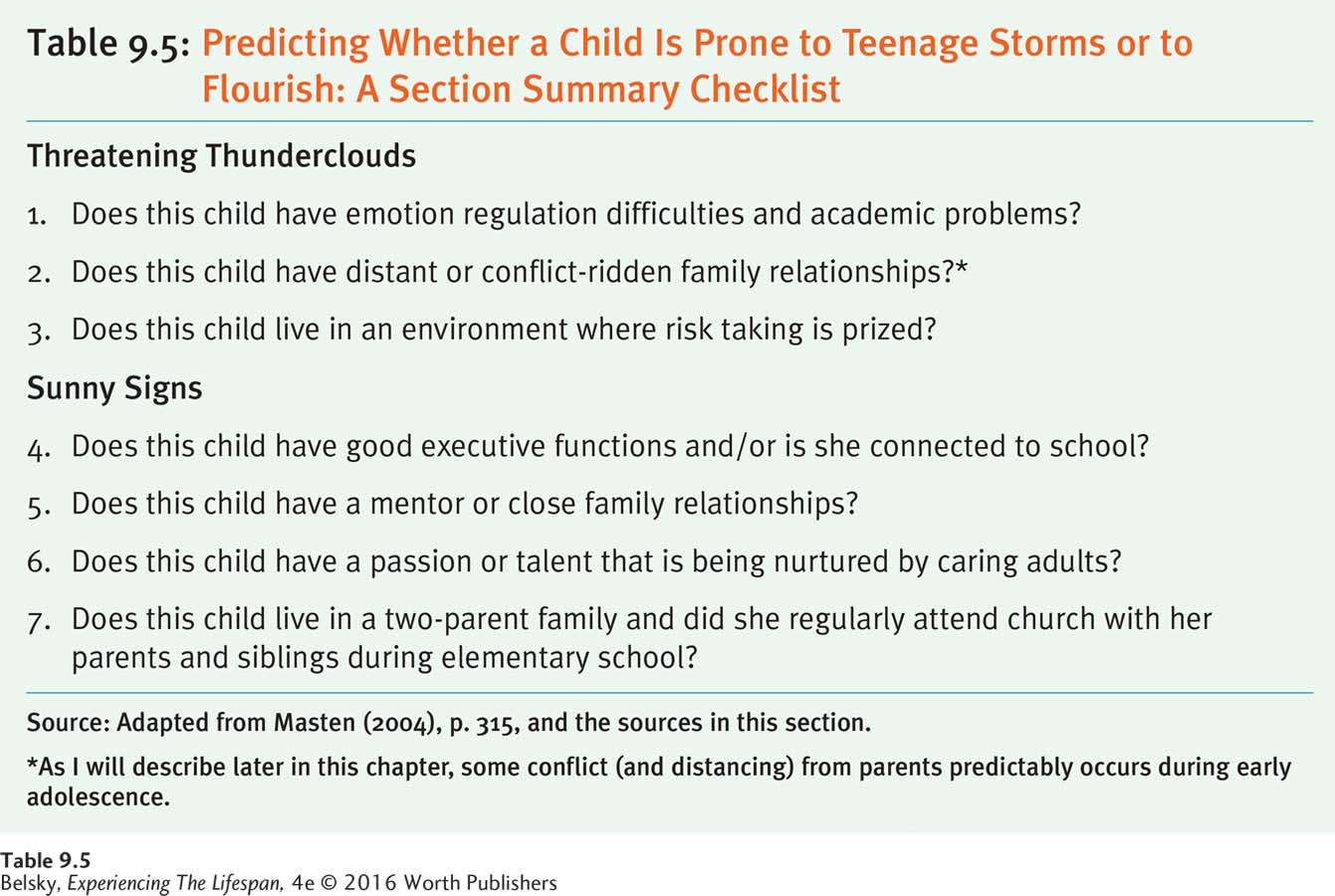

Without denying that serious adolescent difficulties can unpredictably erupt, here are three thunderclouds that foreshadow stormy weather ahead:

AT-

Therefore, tests of executive functions—measures charting whether girls and boys are having difficulties generally thinking through their behavior—

AT-

In essence, these young people were describing an insecure attachment. Teenagers want to be listened to and respected. They need to know they are unconditionally loved (Allen and others, 2007). So, to use the attachment metaphor spelled out in Chapter 4, with adolescents, parents must be skillful dancers. They should understand when to back off and when to stay close. In Chapter 7’s terms, adolescents require an authoritative discipline style.

Given what you learned in previous chapters, it comes as no surprise that parent–

This brings up the fact that the attachment dance at any age is bidirectional. When we see correlations between teenagers’ reporting distant family relationships and having troubles, it’s not simply parents who are at fault. Imagine that you are a 15-

Yes, it’s easy to say that being authoritative is vital in parenting teens. But take it from me (I’ve been there!), when your teenager is on the road to trouble, confronting him about his activities is apt to backfire. So, it can be difficult for frantic parents to understand how to really act authoritatively in a much-

AT-

Which Teens Flourish?

In high school I really got it together. I connected with my lifelong love of music. I’ll never forget that feeling when I got that special prize in band my senior year.

At about age 15, I decided the best way to keep myself off the streets was to get involved in my church youth group. It was my best time of life.

As the quotations show, these attributes offer a mirror image of the qualities I just described: Teenagers thrive when they have superior executive functions and can thoughtfully direct their lives (Gestsdottir and others, 2010; Urban, Lewin-

Thriving does not mean staying out of trouble. Adolescents who are flourishing may also engage in considerable risk taking during the early and middle teens (Lerner and others, 2010). So again, we need to approach adolescent behavior by adopting the developmental systems approach. Those human beings called teens, like human beings of any age, are not all angel or devil, but complex mixtures of frailties and strengths (Larson & Tran, 2014). Testing the limits is a normal adolescent experience even among the happiest, healthiest teens.

And let’s not give up on children who do get seriously derailed. Developmentalists make a distinction between adolescence-

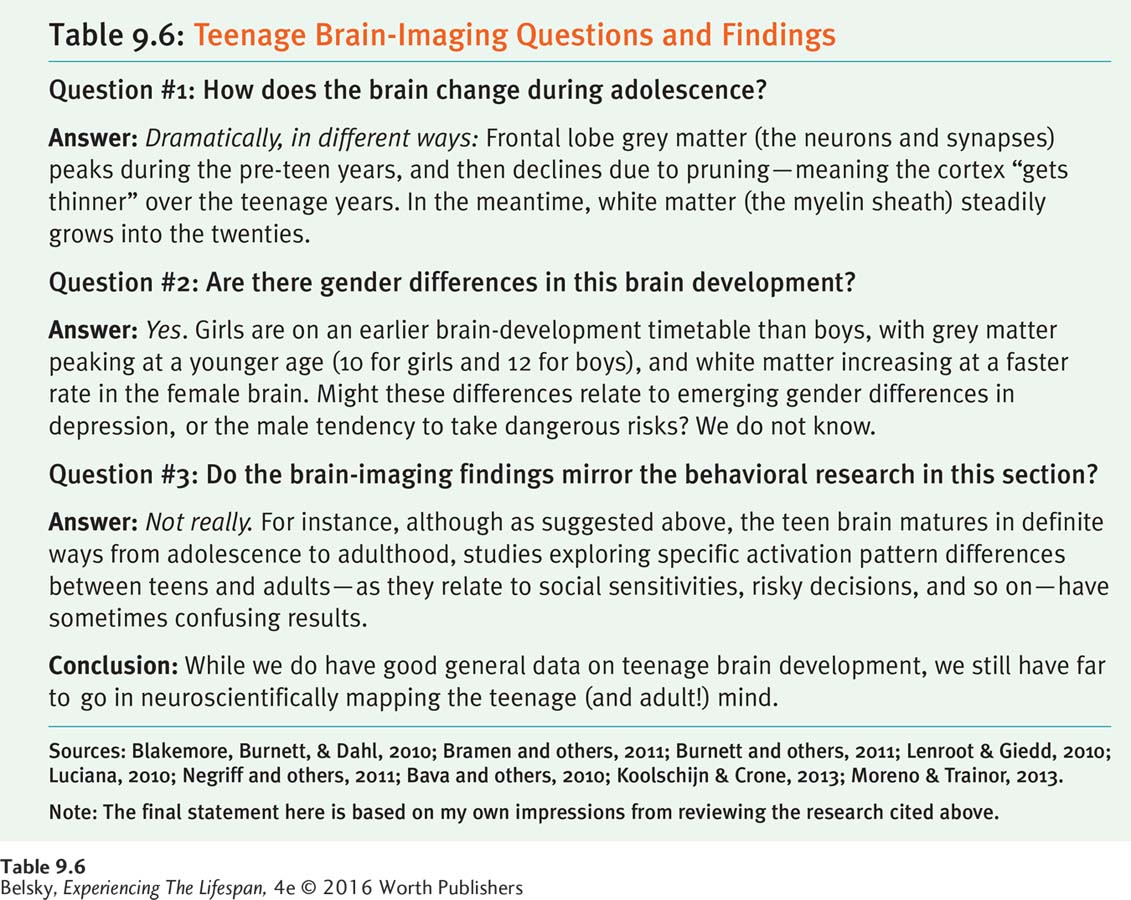

Wrapping Things Up: The Blossoming Teenage Brain

Now, let’s put it all together: the mental growth; the morality; the emotionality; and the sensitivity to what others think. Give teenagers an intellectual problem and they reason in mature ways. But younger teens tend to be captivated by popularity, and get overwhelmed in arousing situations when with their friends.

According to adolescence specialists, these qualities make sense when we look at the developing brain. During the teens, a dramatic pruning occurs in the frontal lobes (see Table 9.6). The insulating myelin sheath has years to go before reaching its mature form. At the same time, puberty heightens the output of certain neurotransmitters, which provokes the passion to take risks (Guerri & Pascual, 2010; Steinberg, 2010). As Laurence Steinberg (2008; Smith, Chein, & Steinberg, 2013) explains, it’s like starting the engine of adulthood with an unskilled driver. This heightened activation of the “socioemotional brain,” with a cognitive control center still “under construction,” makes adolescence a potentially dangerous time.

But from an evolutionary standpoint, it is logical to start with an emotional engine in high gear. Teenagers’ risk-

INTERVENTIONS: Making the World Fit the Teenage Mind

Table 9.7 summarizes these section messages in a chart for parents. Now, let’s explore our discussion’s ramifications for society.

Don’t punish adolescents as if they were mentally just like adults. If the adolescent brain is a work in progress, it doesn’t make sense to have the same legal sanctions for teenagers who commit crimes that we have for adults. Rather than locking adolescents up, it seems logical that at this young age we focus on rehabilitation. As Laurence Steinberg (2008) and virtually every other adolescence expert suggest, with regard to the legal system, “less guilty by reason of adolescence” is the way to go.

Is the U.S. legal system listening to the adolescence specialists? The answer is “a bit, but only recently.” In 2005, the Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty for adolescents and, in 2012, eliminated mandatory life sentences without the possibility of parole for teens (Shulman & Cauffman, 2013). Still, today, as the Experiencing the Lifespan Box suggests, officers and prosecutors can transfer selected adolescents accused of violent crimes out of the juvenile justice system and have those teens tried as adults. Yes, as my amazing interview with Jason suggests, with luck and a resilient temperament, a shockingly punitive approach can help turn a person around. However, statistically speaking, there is no evidence that condemning adolescents to the gulag of dysfunctional adult prisons deters later criminal acts (Fabian, 2011). Do you believe that it’s ever acceptable to try teenagers as adults?

Pass laws user-

Experiencing the Lifespan: Innocently Imprisoned at 16

If you think the U.S. legal system protects 16-

I grew up with crazy stuff. My mom was a drug dealer and my dad passed away so I was adopted by my grandparents. I was kicked out of four schools before ninth grade. By age 15, I was involved with a street gang and heavy gun trading in Birmingham, Alabama. I was in a car with some older guys during a drive-

The original charge was carrying a concealed weapon, and I was sent to a juvenile boot camp. Then, two days after being discharged, detectives were knocking on my door with the full charges: three counts of attempted murder. The arresting officers decided to transfer me to county jail, where I ended up for 19 months. If you go to trial and lose, you get the maximum sentence, 20 years to life, so—

Jail was unbelievable. The ninth floor of the Jefferson County Jail is well known because that’s where they send criminals from the penitentiary who have committed the most violent crimes to await trial. My first cellmate had cut a guy’s head off. Every time you get to know a group, the next week another group arrives in jail and you have to fight again. The guards were no better. If they didn’t like a prisoner, they would persuade inmates to beat the living daylights out of that person.

What helped me cope were my dreams, because you are not in jail in your dreams. I wrote constantly, read all the time. What ultimately helped was being sent out of state (so I couldn’t get involved with my old friends) and, especially, my counselors at the mission. I never met guys so humble; such amazing people. Also, if I got into trouble again, I knew where I could be heading. Scared the heck out of me. Now, everything I do is dependent on being normal. I’m 22. I have good friends but I haven’t told anyone anything about my past. I have a 3.5 average. I’m working two jobs. I’ll be the first person in my family to graduate college. I want to go to grad school to get my psychology Ph.D.

Provide group activities that capitalize on adolescents’ strengths. How can we help teenagers forge growth-

Youth development programs fulfill this mission. They give adolescents safe places to explore their passions during the late afternoon hours, when teens are most prone to get into trouble while hanging out with their friends (Goldner and others, 2011). From 4-

I wish I could say that every youth program fostered flourishing. But as anyone who has spent time at a girls’ club or the local Y knows, these settings can encourage group bullying and antisocial acts (Rorie and others, 2011). Therefore, youth programs must be structured and well supervised. They have to promote the five C’s. At the same time, they should be places where young people can exercise their autonomy and relax, let loose, or joke around (Adachi & Willoughby, 2014). So, rather than just saying, “Afterschool activities are great,” we need to consider what each specific program actually provides.

It also helps to embed less academic offerings into the school day. In one heartening study, having strong high school arts programs boosted children’s academic performance, making students feel more engaged in all of their classes (Martin and others, 2013). Intense involvement, specifically in high school clubs, predicts work success years down the road (Gardner, Roth, & Brooks-

Change high schools to provide a better adolescent–

Unfortunately, however, many Western high schools are not nurturing places. In one disheartening international poll, although teenagers were generally upbeat about other aspects of their lives, they rated their high school experience as only “so-

In surveys, teenagers say that they are yearning for the experiences that characterize high-

In addition to injecting more creativity into the day through the arts, service-

Finally, we might rethink the school day to take into account teenagers’ unique sleep requirements. During early adolescence, the sleep cycle is biologically pushed back (Colrain & Baker, 2011; Feinberg & Campbell, 2010). Although adolescents often need at least nine hours of sleep to function at their best, because they tend to go to bed after 11 and must wake up for school at 6 or 7 a.m., the typical U.S. teen sleeps fewer than 7 hours each day (Colrain & Baker, 2011). Worse yet, children who strongly show this evening circadian shift are generally at risk for a stormy teenage life. They tend to have poorer family relationships (Díaz-

For this reason, researchers are exploring how strategies such as reducing ambient light at night might better promote teenage sleep (Shochat, Cohen-

Think back to your high school—

Another Perspective on the Teenage Mind

Until now, I’ve been highlighting the mainstream developmental science message: “Because of their brain immaturity, teens need protection from the world.” Let’s consider some different views: Do we know enough about how the brain functions to make these kinds of neural attributions? Given the somewhat confusing findings in Table 9.6, some experts legitimately answer no (Epstein, 2010; Sercombe, 2010). Might scientists be over-

Consider, for instance, that the brain evidence targeting the early teens as a time for trouble is out of sync with many real-

The most innovative critique of the immature adolescent brain was put forth by psychologist Robert Epstein. Epstein (2010) reminds us that the life stage called adolescence is an artificial construction. Nature intended us to enter adulthood at puberty. Now young people may be forced into depression and dangerous risk taking by languishing for a decade under the ill-

Tying It All Together

Question 9.1

Robin, a teacher, is about to transfer from fourth grade to the local high school, and she is excited by all the things that her older students will be able to do. Based on what you have learned about Piaget’s formal operational stage and Kohlberg’s theory of moral reasoning, pick out which two new capacities Robin may find among her students.

The high schoolers will be able to memorize poems.

The high schoolers will be able to summarize the plots of stories.

The high schoolers will be able to debate different ideas even if they don’t personally agree with them.

The high schoolers will be able to develop their own moral principles.

c and d

Question 9.2

Eric is the coach of a basketball team. The year-

If your arguments centered on getting punished or rewarded (the coach needs to put Terry in because that’s his best shot at winning; or, the coach can’t put Terry in because, if someone finds out, he will be in trouble), you are reasoning at the preconventional level. Comments such as “going against the rules is wrong” might be classified as conventional. If you argued, “Putting Terry in goes against my values, no matter what the team or the rules say,” your response might qualify as postconventional.

Question 9.3

A 14-

the imaginary audience; the personal fable; adolescent egocentrism

Question 9.4

In your 15-

depression

Question 9.5

Your child has finally made it into the popular kids crowd at school. You should feel (Pick one): proud because that means he is able to get along with the kids/worried because he may be at risk for acting out behaviors such as aggression.

worried, because he is at risk for acting out behaviors such as aggression

Question 9.6

There has been a rise in teenage crimes in your town, and you are at a community meeting to explore solutions. Given what you know about the teenage mind, which two interventions should you definitely support?

Push the state legislature to punish teenage offenders as adults. Let them pay for their crimes!

Encourage the local high school to expand its menu of arts classes.

Think about postponing the beginning of the school day to 10 a.m.

b and c

Question 9.7

Imagine you are a college debater. Use your formal operational skills to argue first for and then against the proposition that society should try teens as adults.

Trying teens as adults. Pro arguments: Kohlberg’s theory clearly implies teens know right from wrong, so if teens knowingly do the crime, they should “do the time.” Actually, the critical dimension in deciding on adult punishment should be a person’s culpability—