11.3Carbohydrates Can Be Linked to Proteins to Form Glycoproteins

Carbohydrates Can Be Linked to Proteins to Form Glycoproteins

A carbohydrate group can be covalently attached to a protein to form a glycoprotein. Such modifications are not rare, as 50% of the proteome consists of glycoproteins. We will examine three classes of glycoproteins. The first class is simply referred to as glycoproteins. In glycoproteins of this class, the protein constituent is the largest component by weight. This versatile class plays a variety of biochemical roles. Many glycoproteins are components of cell membranes, where they take part in processes such as cell adhesion and the binding of sperm to eggs. Other glycoproteins are formed by linking carbohydrates to soluble proteins. Many of the proteins secreted from cells are glycosylated, or modified by the attachment of carbohydrates, including most proteins present in the serum component of blood.

326

The second class of glycoproteins comprises the proteoglycans. The protein component of proteoglycans is conjugated to a particular type of polysaccharide called a glycosaminoglycan. Carbohydrates make up a much larger percentage by weight of the proteoglycan compared with simple glycoproteins. Proteoglycans function as structural components and lubricants.

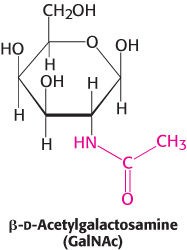

Mucins, or mucoproteins, are, like proteoglycans, predominantly carbohydrate. N-Acetylgalactosamine is usually the carbohydrate moiety bound to the protein in mucins. N -Acetylgalactosamine is an example of an amino sugar, so named because an amino group replaces a hydroxyl group. Mucins, a key component of mucus, serve as lubricants.

Glycosylation greatly increases the complexity of the proteome. A given protein with several potential glycosylation sites can have many different glycosylated forms (called glycoforms), each of which can be generated only in a specific cell type or developmental stage.

Carbohydrates can be linked to proteins through asparagine (N-linked) or through serine or threonine (O-linked) residues

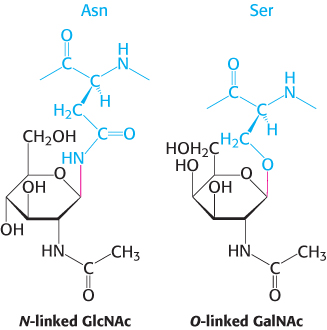

Sugars in glycoproteins are attached either to the amide nitrogen atom in the side chain of asparagine (termed an N-

327

The glycoprotein erythropoietin is a vital hormone

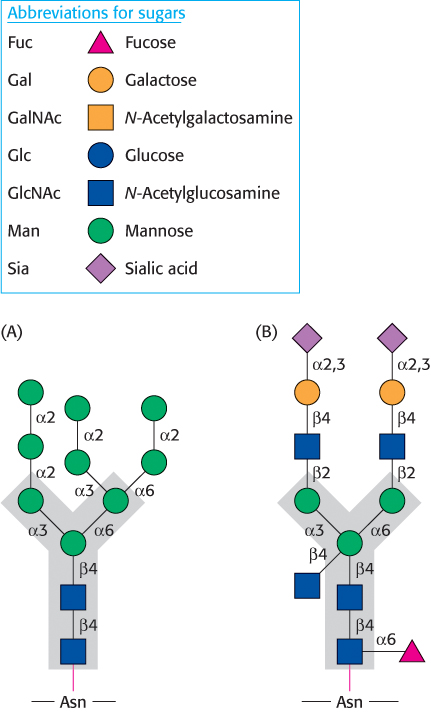

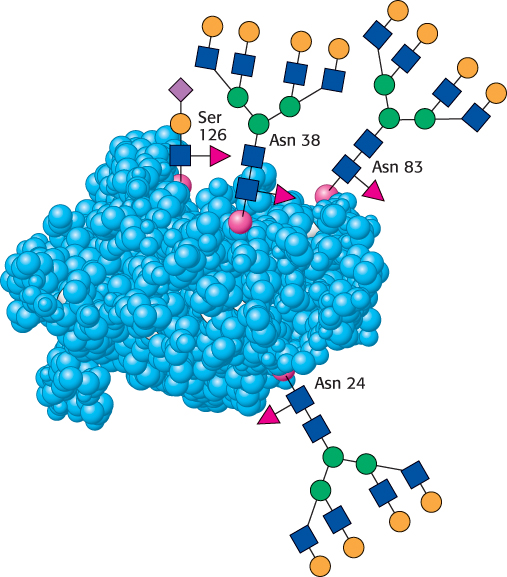

Let us look at a glycoprotein present in the blood serum that has dramatically improved treatment for anemia, particularly that induced by cancer chemotherapy. The glycoprotein hormone erythropoietin (EPO) is secreted by the kidneys and stimulates the production of red blood cells. EPO is composed of 165 amino acids and is N-glycosylated at three asparagine residues and O-glycosylated on a serine residue (Figure 11.17). The mature EPO is 40% carbohydrate by weight, and glycosylation enhances the stability of the protein in the blood. Unglycosylated protein has only about 10% of the bioactivity of the glycosylated form because the protein is rapidly removed from the blood by the kidneys. The availability of recombinant human EPO has greatly aided the treatment of anemias. However, some endurance athletes have used recombinant human EPO to increase the red-

Let us look at a glycoprotein present in the blood serum that has dramatically improved treatment for anemia, particularly that induced by cancer chemotherapy. The glycoprotein hormone erythropoietin (EPO) is secreted by the kidneys and stimulates the production of red blood cells. EPO is composed of 165 amino acids and is N-glycosylated at three asparagine residues and O-glycosylated on a serine residue (Figure 11.17). The mature EPO is 40% carbohydrate by weight, and glycosylation enhances the stability of the protein in the blood. Unglycosylated protein has only about 10% of the bioactivity of the glycosylated form because the protein is rapidly removed from the blood by the kidneys. The availability of recombinant human EPO has greatly aided the treatment of anemias. However, some endurance athletes have used recombinant human EPO to increase the red-

Glycosylation functions in nutrient sensing

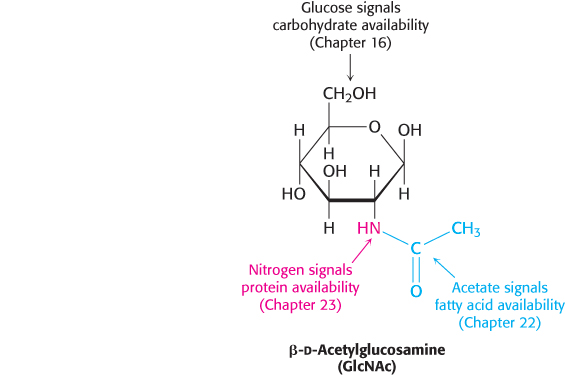

An especially important glycosylation reaction is the covalent attachment of N-

Proteoglycans, composed of polysaccharides and protein, have important structural roles

As stated earlier, proteoglycans are proteins attached to glycosaminoglycans. The glycosaminoglycan makes up as much as 95% of the biomolecule by weight, and so the proteoglycan resembles a polysaccharide more than a protein. Proteoglycans not only function as lubricants and structural components in connective tissue, but also mediate the adhesion of cells to the extracellular matrix, and bind factors that regulate cell proliferation.

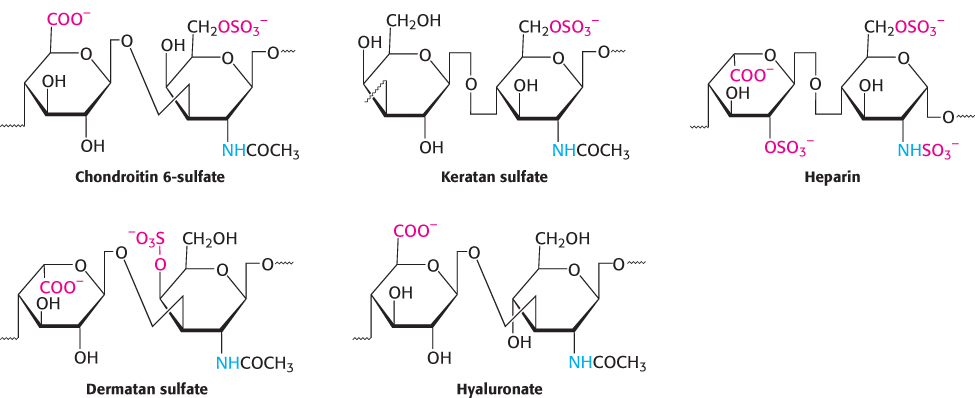

The properties of proteoglycans are determined primarily by the glycosaminoglycan component. Many glycosaminoglycans are made of repeating units of disaccharides containing a derivative of an amino sugar, either glucosamine or galactosamine (Figure 11.19). At least one of the two sugars in the repeating unit has a negatively charged carboxylate or sulfate group. The major glycosaminoglycans in animals are chondroitin sulfate, keratan sulfate, heparin, dermatan sulfate, and hyaluronate. Recall that heparin acts as an anticoagulant to assist the termination of blood clotting. Mucopolysaccharidoses are a collection of diseases, such as Hurler disease, that result from the inability to degrade glycosaminoglycans (Figure 11.20). Although precise clinical features vary with the disease, all mucopolysaccharidoses result in skeletal deformities and reduced life expectancies.

The properties of proteoglycans are determined primarily by the glycosaminoglycan component. Many glycosaminoglycans are made of repeating units of disaccharides containing a derivative of an amino sugar, either glucosamine or galactosamine (Figure 11.19). At least one of the two sugars in the repeating unit has a negatively charged carboxylate or sulfate group. The major glycosaminoglycans in animals are chondroitin sulfate, keratan sulfate, heparin, dermatan sulfate, and hyaluronate. Recall that heparin acts as an anticoagulant to assist the termination of blood clotting. Mucopolysaccharidoses are a collection of diseases, such as Hurler disease, that result from the inability to degrade glycosaminoglycans (Figure 11.20). Although precise clinical features vary with the disease, all mucopolysaccharidoses result in skeletal deformities and reduced life expectancies.

328

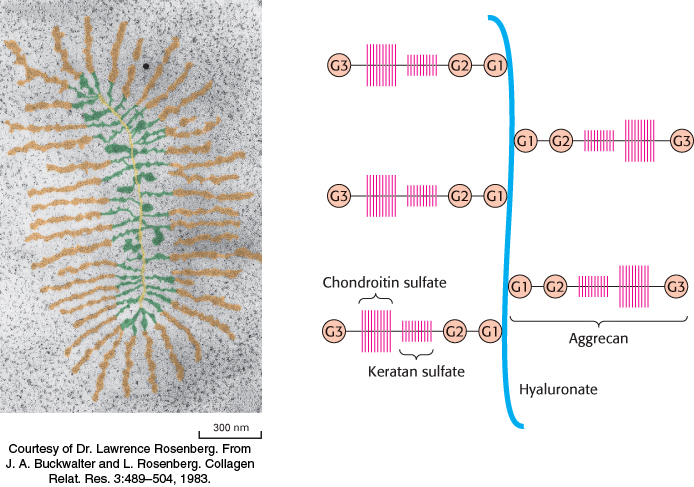

Proteoglycans are important components of cartilage

Among the best-

329

In addition to being a key component of structural tissues, glycosaminoglycans are common throughout the biosphere. Chitin is a glycosaminoglycan found in the exoskeleton of insects, crustaceans, and arachnids and is, next to cellulose, the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (Figure 11.22). Cephalopods such as squid use their razor sharp beaks, which are made of extensively crosslinked chitin, to disable and consume prey.

Mucins are glycoprotein components of mucus

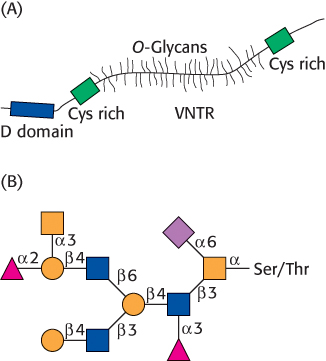

A third class of glycoproteins is the mucins (mucoproteins). In mucins, the protein component is extensively glycosylated at serine or threonine residues by N-acetylgalactosamine (Figure 11.10). Mucins are capable of forming large polymeric structures and are common in mucous secretions. These glycoproteins are synthesized by specialized cells in the tracheobronchial, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts. Mucins are abundant in saliva where they function as lubricants.

A model of a mucin is shown in Figure 11.23A. The defining feature of the mucins is a region of the protein backbone termed the variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) region, which is rich in serine and threonine residues that are O-glycosylated. Indeed, the carbohydrate moiety can account for as much as 80% of the molecule by weight. A number of core carbohydrate structures are conjugated to the protein component of mucin. Figure 11.23B shows one such structure.

Mucins adhere to epithelial cells and act as a protective barrier; they also hydrate the underlying cells. In addition to protecting cells from environmental insults, such as stomach acid, inhaled chemicals in the lungs, and bacterial infections, mucins have roles in fertilization, the immune response, and cell adhesion. Mucins are overexpressed in bronchitis and cystic fibrosis, and the overexpression of mucins is characteristic of adeno-

Mucins adhere to epithelial cells and act as a protective barrier; they also hydrate the underlying cells. In addition to protecting cells from environmental insults, such as stomach acid, inhaled chemicals in the lungs, and bacterial infections, mucins have roles in fertilization, the immune response, and cell adhesion. Mucins are overexpressed in bronchitis and cystic fibrosis, and the overexpression of mucins is characteristic of adeno-

330

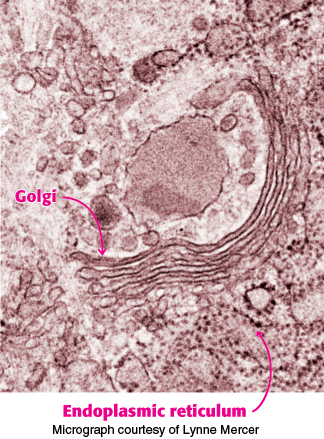

Protein glycosylation takes place in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum and in the Golgi complex

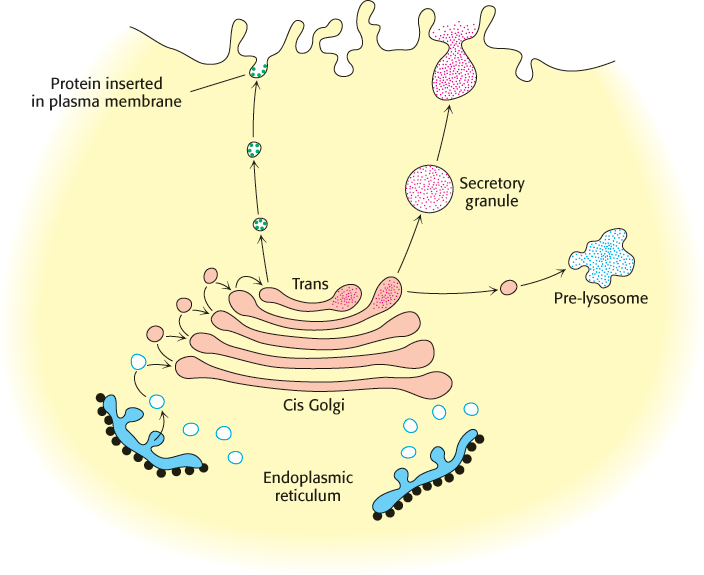

The major pathway for protein glycosylation takes place inside the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and in the Golgi complex, organelles that play central roles in protein trafficking (Figure 11.24). The protein is synthesized by ribosomes attached to the cytoplasmic face of the ER membrane, and the peptide chain is inserted into the lumen of the ER (Section 30.6). The N-linked glycosylation begins in the ER and continues in the Golgi complex, whereas the O-linked glycosylation takes place exclusively in the Golgi complex.

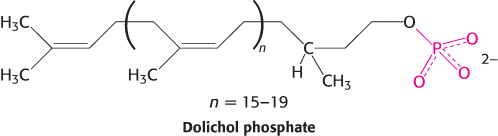

A large oligosaccharide destined for attachment to the asparagine residue of a protein is assembled on dolichol phosphate, a specialized lipid molecule located in the ER membrane and containing about 20 isoprene (C5) units.

The terminal phosphate group of the dolichol phosphate is the site of attachment of the oligosaccharide. This activated (energy-

Proteins in the lumen of the ER and in the ER membrane are transported to the Golgi complex, which is a stack of flattened membranous sacs. Carbohydrate units of glycoproteins are altered and elaborated in the Golgi complex. The O -linked sugar units are fashioned there, and the N-linked sugars, arriving from the ER as a component of a glycoprotein, are modified in many different ways. The Golgi complex is the major sorting center of the cell. Proteins proceed from the Golgi complex to lysosomes, secretory granules, or the plasma membrane, according to signals encoded within their amino acid sequences and three-

331

Specific enzymes are responsible for oligosaccharide assembly

How are the complex carbohydrates formed, be they unconjugated molecules such as glycogen or components of glycoproteins? Complex carbohydrates are synthesized through the action of specific enzymes, glycosyltransferases, which catalyze the formation of glycosidic bonds. Given the diversity of known glycosidic linkages, many different enzymes are required. Indeed, glycosyltransferases account for 1% to 2% of gene products in all organisms examined.

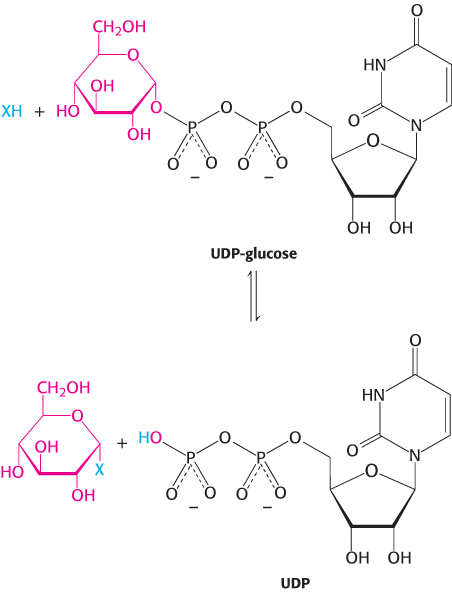

While dolichol phosphate-

Blood groups are based on protein glycosylation patterns

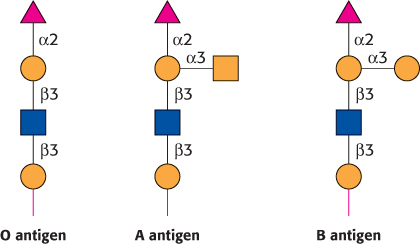

The human ABO blood groups illustrate the effects of glycosyltransferases on the formation of glycoproteins. Each blood group is designated by the presence of one of the three different carbohydrates, termed A, B, or O, attached to glycoproteins and glycolipids on the surfaces of red blood cells (Figure 11.27). These structures have in common an oligosaccharide foundation called the O (or sometimes H) antigen. The A and B antigens differ from the O antigen by the addition of one extra monosaccharide, either N-acetylgalactosamine (for A) or galactose (for B) through an α -1,3 linkage to a galactose moiety of the O antigen.

The human ABO blood groups illustrate the effects of glycosyltransferases on the formation of glycoproteins. Each blood group is designated by the presence of one of the three different carbohydrates, termed A, B, or O, attached to glycoproteins and glycolipids on the surfaces of red blood cells (Figure 11.27). These structures have in common an oligosaccharide foundation called the O (or sometimes H) antigen. The A and B antigens differ from the O antigen by the addition of one extra monosaccharide, either N-acetylgalactosamine (for A) or galactose (for B) through an α -1,3 linkage to a galactose moiety of the O antigen.

Specific glycosyltransferases add the extra monosaccharide to the O antigen. Each person inherits the gene for one glycosyltransferase of this type from each parent. The type A transferase specifically adds N-acetylgalactosamine, whereas the type B transferase adds galactose. These enzymes are identical in all but 4 of 354 positions. The O phenotype is the result of a mutation in the O transferase that results in the synthesis of an inactive enzyme.

These structures have important implications for blood transfusions and other transplantation procedures. If an antigen not normally present in a person is introduced, the person’s immune system recognizes it as foreign. Red-

Why are different blood types present in the human population? Suppose that a pathogenic organism such as a parasite expresses on its cell surface a carbohydrate antigen similar to one of the blood-

Why are different blood types present in the human population? Suppose that a pathogenic organism such as a parasite expresses on its cell surface a carbohydrate antigen similar to one of the blood-

332

Errors in glycosylation can result in pathological conditions

Although the role of carbohydrate attachment to proteins is not known in detail in most cases, data indicate that this glycosylation is important for the processing and stability of these proteins, as it is for EPO. Certain types of muscular dystrophy can be traced to improper glycosylation of dystroglycan, a membrane protein that links the extracellular matrix with the cytoskeleton. Indeed, an entire family of severe inherited human diseases called congenital disorders of glycosylation has been identified. These pathological conditions reveal the importance of proper modification of proteins by carbohydrates and their derivatives.

Although the role of carbohydrate attachment to proteins is not known in detail in most cases, data indicate that this glycosylation is important for the processing and stability of these proteins, as it is for EPO. Certain types of muscular dystrophy can be traced to improper glycosylation of dystroglycan, a membrane protein that links the extracellular matrix with the cytoskeleton. Indeed, an entire family of severe inherited human diseases called congenital disorders of glycosylation has been identified. These pathological conditions reveal the importance of proper modification of proteins by carbohydrates and their derivatives.

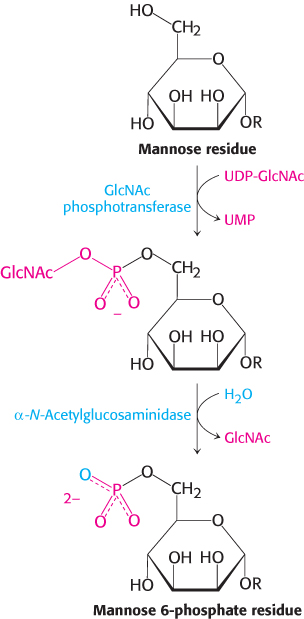

An especially clear example of the role of glycosylation is provided by I-

Oligosaccharides can be “sequenced”

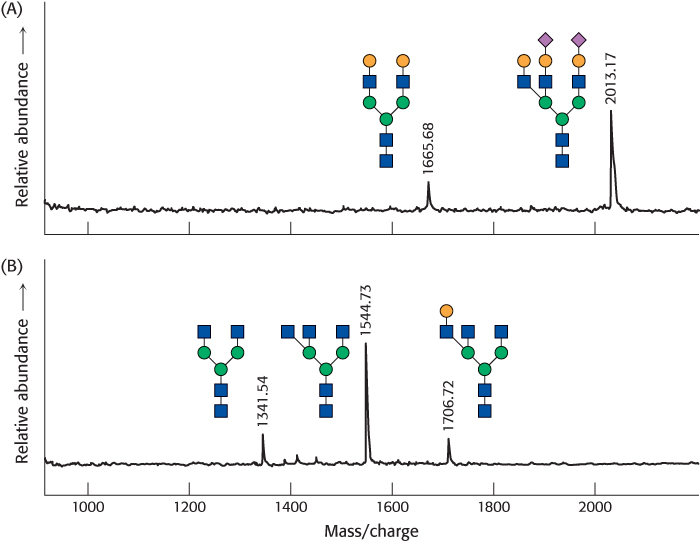

How is it possible to determine the structure of a glycoprotein—

The first step is to detach the oligosaccharide from the protein. For example, N-linked oligosaccharides can be released from proteins by an enzyme such as peptide N-

333

Proteases applied to glycoproteins can reveal the points of oligosaccharide attachment. Cleavage by a specific protease yields a characteristic pattern of peptide fragments that can be analyzed chromatographically. Fragments attached to oligosaccharides can be picked out because their chromatographic properties will change on glycosidase treatment. Mass spectrometric analysis or direct peptide sequencing can reveal the identity of the peptide in question and, with additional effort, the exact site of oligo-

While the sequencing of the human genome is complete, the characterization of the much more complex proteome, including the biological roles of glycosylated proteins, presents a challenge to biochemistry.