24.1Nitrogen Fixation: Microorganisms Use ATP and a Powerful Reductant to Reduce Atmospheric Nitrogen to Ammonia

Nitrogen Fixation: Microorganisms Use ATP and a Powerful Reductant to Reduce Atmospheric Nitrogen to Ammonia

The nitrogen in amino acids, purines, pyrimidines, and other biomolecules ultimately comes from atmospheric nitrogen, N2. The biosynthetic process starts with the reduction of N2 to NH3 (ammonia), a process called nitrogen fixation. The extremely strong N ≡ N bond, which has a bond energy of 940 kJ mol−1 (225 kcal mol−1), is highly resistant to chemical attack. Indeed, Antoine Lavoisier named nitrogen gas “azote,” from Greek words meaning “without life,” because it is so unreactive. Nevertheless, the conversion of nitrogen and hydrogen to form ammonia is thermodynamically favorable; the reaction is difficult kinetically because of the activation energy required to form intermediates along the reaction pathway.

Although higher organisms are unable to fix nitrogen, this conversion is carried out by some bacteria and archaea. Symbiotic Rhizobium bacteria invade the roots of leguminous plants and form root nodules in which they fix nitrogen, supplying both the bacteria and the plants. The importance of nitrogen fixation by diazotrophic (nitrogen-

715

The fixation of N2 is typically carried out by mixing with H2 gas over an iron catalyst at about 500°C and a pressure of 300 atmospheres.

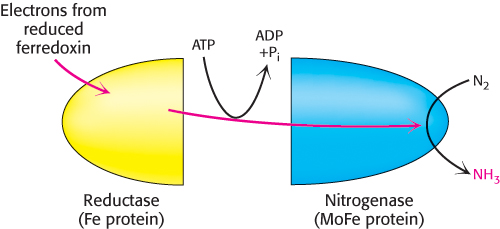

To meet the kinetic challenge, the biological process of nitrogen fixation requires a complex enzyme with multiple redox centers. The nitrogenase complex, which carries out this fundamental transformation, consists of two proteins: a reductase (also called the iron protein or Fe protein), which provides electrons with high reducing power, and nitrogenase (also called the molybdenum–

In principle, the reduction of N2 to NH3 is a six-

However, the biological reaction always generates at least 1 mol of H2 in addition to 2 mol of NH3 for each mol of N ≡ N. Hence, an input of two additional electrons is required.

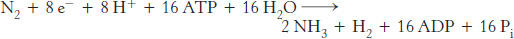

In most nitrogen-

Note that O2 is required for oxidative phosphorylation to generate the ATP necessary for nitrogen fixation. However, the nitrogenase complex is exquisitely sensitive to inactivation by O2. To allow ATP synthesis and nitrogenase to function simultaneously, leguminous plants maintain a very low concentration of free O2 in their root nodules, the location of the nitrogenase. This is accomplished by binding O2 to leghemoglobin, a homolog of hemoglobin (Section 6.3).

The iron–molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase binds and reduces atmospheric nitrogen

Both the reductase and the nitrogenase components of the complex are iron–

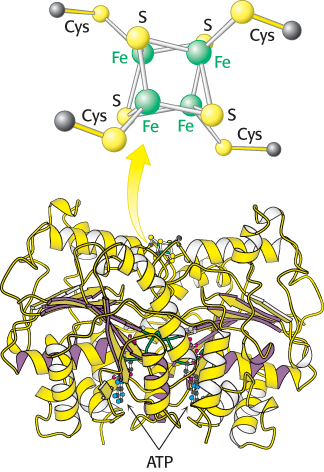

FIGURE 24.2 Fe Protein. This protein is a dimer composed of two polypeptide chains linked by a 4Fe–

FIGURE 24.2 Fe Protein. This protein is a dimer composed of two polypeptide chains linked by a 4Fe–716

The role of the reductase is to transfer electrons from a suitable donor, such as reduced ferredoxin, to the nitrogenase component. The 4Fe–

The role of the reductase is to transfer electrons from a suitable donor, such as reduced ferredoxin, to the nitrogenase component. The 4Fe–

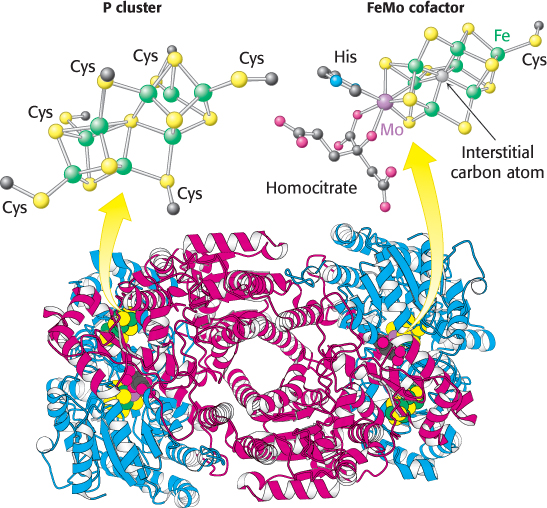

The nitrogenase component is an α2β2 tetramer (240 kDa), in which the α and β subunits are homologous to each other and structurally quite similar (Figure 24.3). The nitrogenase requires the FeMo cofactor, which consists of [Fe4–S3] and [Mo–

Electrons from the reductase enter at the P clusters, which are located at the α–β interface. The role of the P clusters is to store electrons until they can be used productively to reduce nitrogen at the FeMo cofactor. The FeMo cofactor is the site of nitrogen fixation. One face of the FeMo cofactor is likely to be the site of nitrogen reduction. The electron-

717

Ammonium ion is assimilated into an amino acid through glutamate and glutamine

The next step in the assimilation of nitrogen into biomolecules is the entry of NH4+ into amino acids. The amino acids glutamate and glutamine play pivotal roles in this regard, acting as nitrogen donors for most amino acids. The α-amino group of most amino acids comes from the α-amino group of glutamate by transamination (Section 23.3). Glutamine, the other major nitrogen donor, contributes its side-

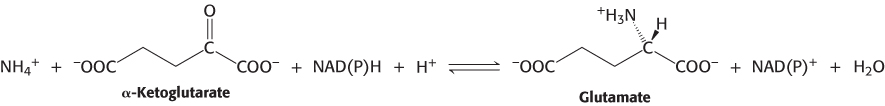

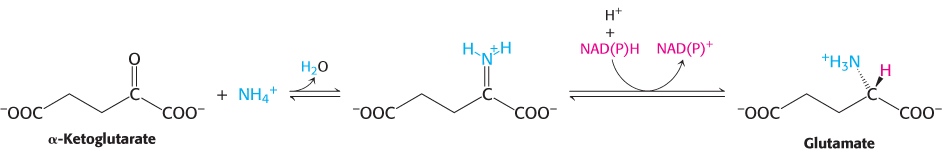

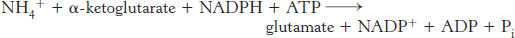

Glutamate is synthesized from NH4+ and α-ketoglutarate, a citric acid cycle intermediate, by the action of glutamate dehydrogenase. We have already encountered this enzyme in the degradation of amino acids (Section 23.3). Recall that NAD+ is the oxidant in catabolism, whereas NADPH is the reductant in biosyntheses. Glutamate dehydrogenase is unusual in that it does not discriminate between NADH and NADPH, at least in some species.

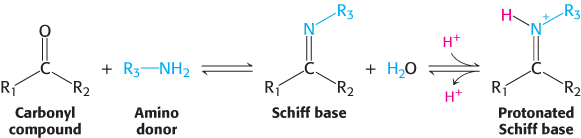

The reaction proceeds in two steps. First, a Schiff base forms between ammonia and α-ketoglutarate. The formation of a Schiff base between an amine and a carbonyl compound is a key reaction that takes place at many stages of amino acid biosynthesis and degradation.

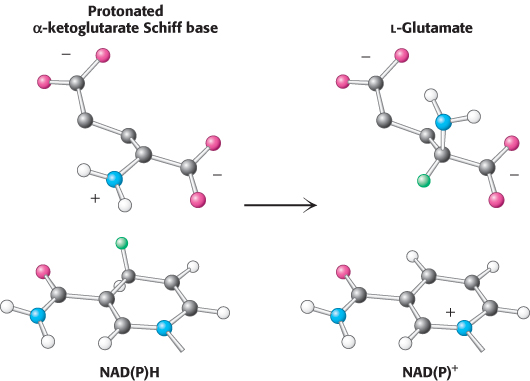

Schiff bases are easily protonated. In the second step, the protonated Schiff base is reduced by the transfer of a hydride ion from NAD(P)H to form glutamate.

This reaction is crucial because it establishes the stereochemistry of the α-carbon atom (S absolute configuration) in glutamate. The enzyme binds the α-ketoglutarate substrate in such a way that hydride transferred from NAD(P)H is added to form the l isomer of glutamate (Figure 24.4). As we shall see, this stereochemistry is established for other amino acids by transamination reactions that rely on pyridoxal phosphate.

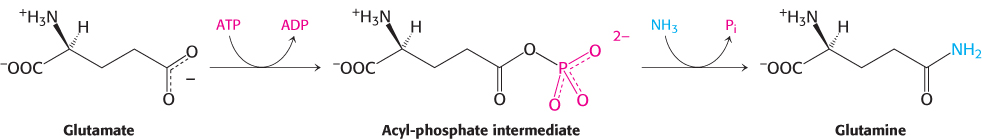

A second ammonium ion is incorporated into glutamate to form glutamine by the action of glutamine synthetase. This amidation is driven by the hydrolysis of ATP. ATP participates directly in the reaction by phosphorylating the side chain of glutamate to form an acylphosphate intermediate, which then reacts with ammonia to form glutamine.

718

A high-

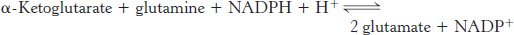

Glutamate dehydrogenase and glutamine synthetase are present in all organisms. Most prokaryotes also contain an evolutionarily unrelated enzyme, glutamate synthase, which catalyzes the reductive amination of α-ketoglutarate to glutamate. Glutamine is the nitrogen donor.

The side-

Note that this stoichiometry differs from that of the glutamate dehydrogenase reaction in that ATP is hydrolyzed. Why do prokaryotes sometimes use this more expensive pathway? The answer is that the value of KM of glutamate dehydrogenase for NH4+ is high (∼ 1 mM), and so this enzyme is not saturated when NH4+ is limiting. In contrast, glutamine synthetase has very low KM for NH4+. Thus, ATP hydrolysis is required to capture ammonia when it is scarce.

719