25.3Deoxyribonucleotides Are Synthesized by the Reduction of Ribonucleotides Through a Radical Mechanism

Deoxyribonucleotides Are Synthesized by the Reduction of Ribonucleotides Through a Radical Mechanism

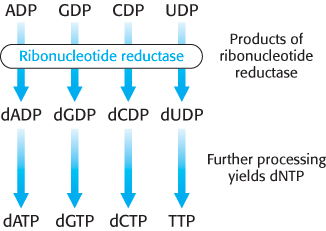

We turn now to the synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. These precursors of DNA are formed by the reduction of ribonucleotides; specifically, the 2′-hydroxyl group on the ribose moiety is replaced by a hydrogen atom. The substrates are ribonucleoside diphosphates, and the ultimate reductant is NADPH. The enzyme ribonucleotide reductase is responsible for the reduction reaction for all four ribonucleotides. The ribonucleotide reductases of different organisms are a remarkably diverse set of enzymes. Yet detailed studies have revealed that they have a common reaction mechanism, and their three-

Mechanism: A tyrosyl radical is critical to the action of ribonucleotide reductase

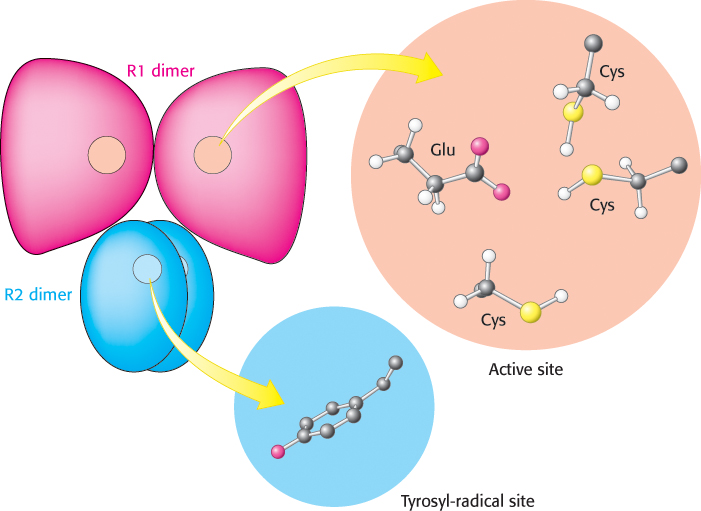

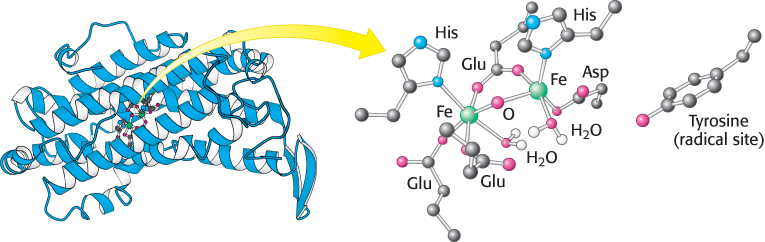

The ribonucleotide reductase of E. coli consists of two subunits: R1 (an 87-

FIGURE 25.10 Ribonucleotide reductase R2 subunit. The R2 subunit contains a stable free radical on a tyrosine residue. This radical is generated by the reaction of oxygen (not shown) at a nearby site containing two iron atoms. Two R2 subunits come together to form a dimer.

FIGURE 25.10 Ribonucleotide reductase R2 subunit. The R2 subunit contains a stable free radical on a tyrosine residue. This radical is generated by the reaction of oxygen (not shown) at a nearby site containing two iron atoms. Two R2 subunits come together to form a dimer.

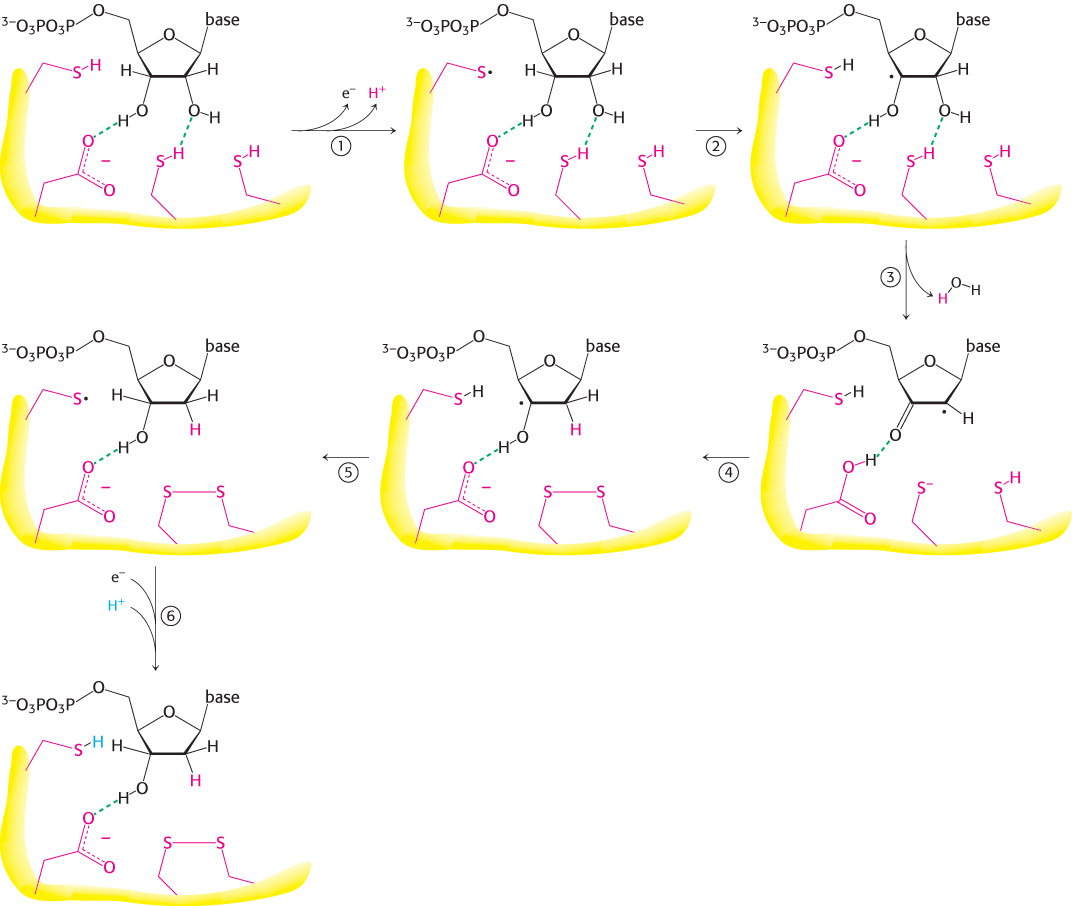

In the synthesis of a deoxyribonucleotide, the OH bonded to C-

754

The reaction begins with the transfer of an electron from a cysteine residue on R1 to the tyrosyl radical on R2. The loss of an electron generates a highly reactive cysteine thiyl radical within the active site of R1.

This radical then abstracts a hydrogen atom from C-

3′ of the ribose unit, generating a radical at that carbon atom. The radical at C-

3′ promotes the release of the OH− from the C- 2′ carbon atom. Protonated by a second cysteine residue, the departing OH− leaves as a water molecule. A hydride ion (a proton with two electrons) is then transferred from a third cysteine residue to complete the reduction of the position, form a disulfide bond, and re-

form a radical. This C-

3′ radical recaptures the same hydrogen atom originally abstracted by the first cysteine residue, and the deoxyribonucleotide is free to leave the enzyme. R2 provides an electron to reduce the thiyl radical. The disulfide bond generated in the enzyme’s active site must then be reduced to regenerate the active enzyme.

755

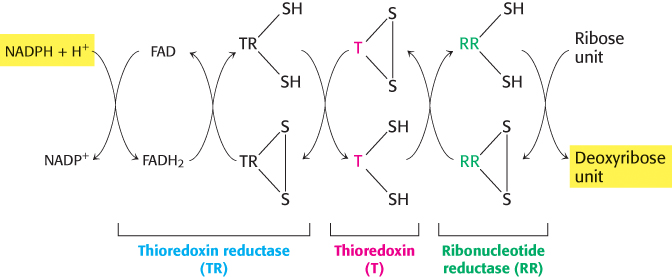

The electrons for this reduction come from NADPH, but not directly. One carrier of reducing power linking NADPH with the reductase is thioredoxin, a 12-

Stable radicals other than tyrosyl radical are employed by other ribonucleotide reductases

Ribonucleotide reductases that do not contain tyrosyl radicals have been characterized in other organisms. Instead, these enzymes contain other stable radicals that are generated by other processes. For example, in one class of reductases, the coenzyme adenosylcobalamin (vitamin B12) is the radical source (Section 22.3). Despite differences in the stable radical employed, the active sites of these enzymes are similar to that of the E. coli ribonucleotide reductase, and they appear to act by the same mechanism, based on the exceptional reactivity of cysteine radicals. Thus, these enzymes have a common ancestor but evolved a range of mechanisms for generating stable radical species that function well under different growth conditions. The primordial enzymes appear to have been inactivated by oxygen, whereas enzymes such as the E. coli enzyme make use of oxygen to generate the initial tyrosyl radical. Note that the reduction of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides is a difficult reaction chemically, likely to require a sophisticated catalyst. The existence of a common protein enzyme framework for this process strongly suggests that proteins joined the RNA world before the evolution of DNA as a stable storage form for genetic information.

Ribonucleotide reductases that do not contain tyrosyl radicals have been characterized in other organisms. Instead, these enzymes contain other stable radicals that are generated by other processes. For example, in one class of reductases, the coenzyme adenosylcobalamin (vitamin B12) is the radical source (Section 22.3). Despite differences in the stable radical employed, the active sites of these enzymes are similar to that of the E. coli ribonucleotide reductase, and they appear to act by the same mechanism, based on the exceptional reactivity of cysteine radicals. Thus, these enzymes have a common ancestor but evolved a range of mechanisms for generating stable radical species that function well under different growth conditions. The primordial enzymes appear to have been inactivated by oxygen, whereas enzymes such as the E. coli enzyme make use of oxygen to generate the initial tyrosyl radical. Note that the reduction of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides is a difficult reaction chemically, likely to require a sophisticated catalyst. The existence of a common protein enzyme framework for this process strongly suggests that proteins joined the RNA world before the evolution of DNA as a stable storage form for genetic information.

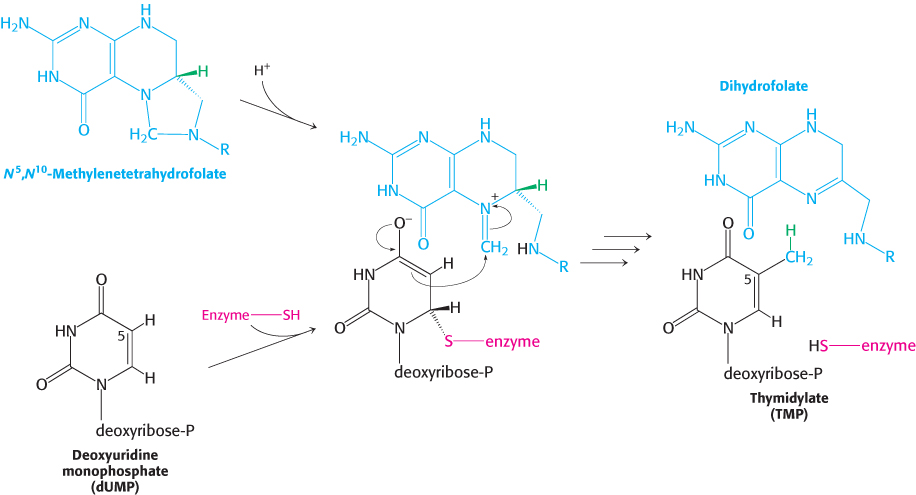

Thymidylate is formed by the methylation of deoxyuridylate

Uracil, produced by the pyrimidine synthesis pathway, is not a component of DNA. Rather, DNA contains thymine, a methylated analog of uracil. Another step is required to generate thymidylate from uracil. Thymidylate synthase catalyzes this finishing touch: deoxyuridylate (dUMP) is methylated to thymidylate (TMP). Recall that thymidylate synthase also functions in the thymine salvage pathway. As will be described in Chapter 28, the methylation of this nucleotide marks sites of DNA damage for repair and, hence, helps preserve the integrity of the genetic information stored in DNA. The methyl donor in this reaction is N5, N10-methylenetetrahydrofolate rather than S-adenosylmethionine (Section 24.2).

The methyl group becomes attached to the C-

756

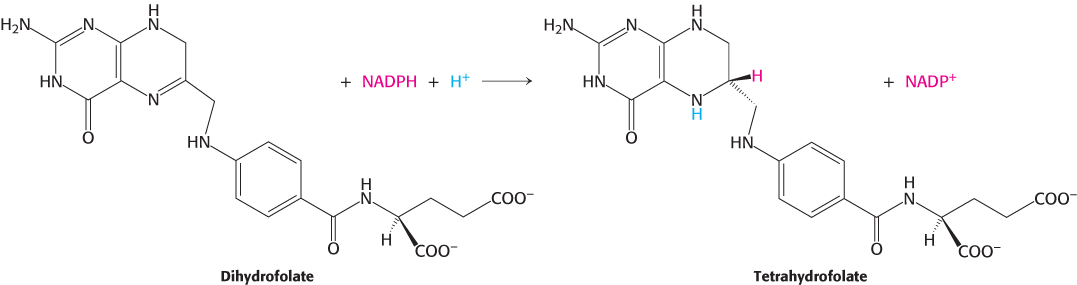

Dihydrofolate reductase catalyzes the regeneration of tetrahydrofolate, a one-carbon carrier

Tetrahydrofolate is regenerated from the dihydrofolate that is produced in the synthesis of thymidylate. This regeneration is accomplished by dihydrofolate reductase with the use of NADPH as the reductant.

A hydride ion is directly transferred from the nicotinamide ring of NADPH to the pteridine ring of dihydrofolate. The bound dihydrofolate and NADPH are held in close proximity to facilitate the hydride transfer.

757

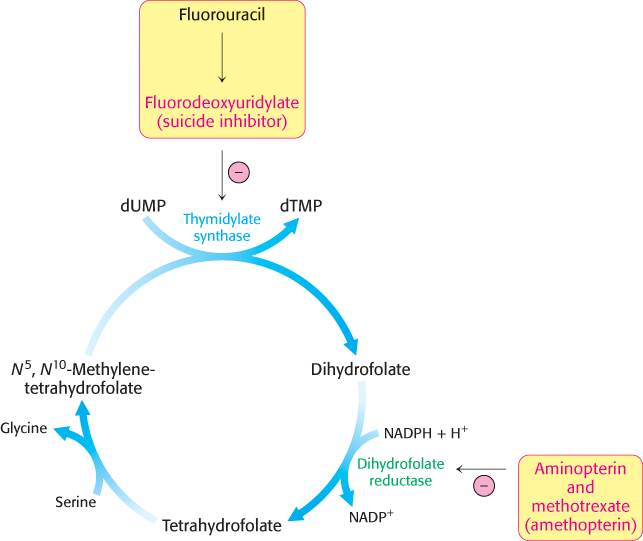

Several valuable anticancer drugs block the synthesis of thymidylate

Rapidly dividing cells require an abundant supply of thymidylate for the synthesis of DNA. The vulnerability of these cells to the inhibition of TMP synthesis has been exploited in the treatment of cancer. Thymidylate synthase and dihydrofolate reductase are choice targets of chemotherapy (Figure 25.13).

Rapidly dividing cells require an abundant supply of thymidylate for the synthesis of DNA. The vulnerability of these cells to the inhibition of TMP synthesis has been exploited in the treatment of cancer. Thymidylate synthase and dihydrofolate reductase are choice targets of chemotherapy (Figure 25.13).

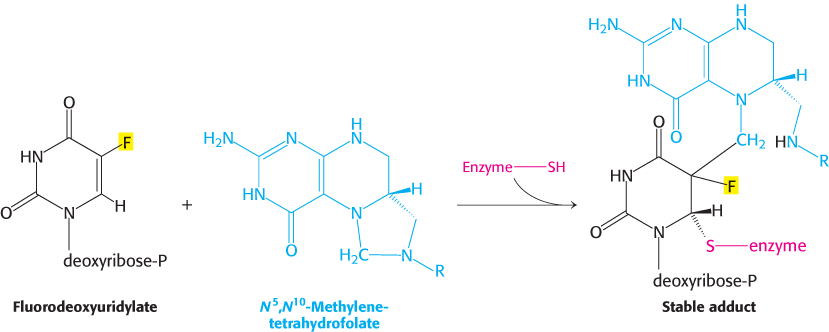

Fluorouracil, an anticancer drug, is converted in vivo into fluorodeoxyuridylate (F-

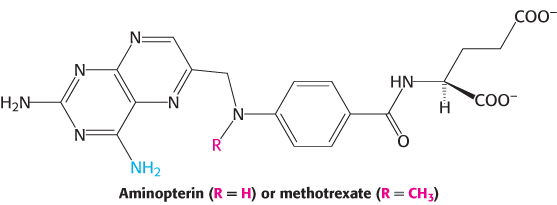

The synthesis of TMP can also be blocked by inhibiting the regeneration of tetrahydrofolate. Analogs of dihydrofolate, such as aminopterin and methotrexate (amethopterin), are potent competitive inhibitors (Ki < 1 nM) of dihydrofolate reductase.

Methotrexate is a valuable drug in the treatment of many rapidly growing tumors, such as those in acute leukemia and choriocarcinoma, a cancer derived from placental cells. However, methotrexate kills rapidly replicating cells whether they are malignant or not. Stem cells in bone marrow, epithelial cells of the intestinal tract, and hair follicles are vulnerable to the action of this folate antagonist, accounting for its toxic side effects, which include weakening of the immune system, nausea, and hair loss.

758

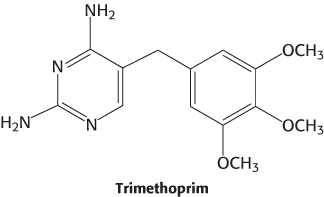

Folate analogs such as trimethoprim have potent antibacterial and antiprotozoal activity. Trimethoprim binds 105-fold less tightly to mammalian dihydrofolate reductase than it does to reductases of susceptible microorganisms. Small differences in the active-