29.2Transcription in Eukaryotes Is Highly Regulated

Transcription in Eukaryotes Is Highly Regulated

We turn now to transcription in eukaryotes, a much more complex process than in bacteria. Eukaryotic cells have a remarkable ability to regulate precisely the time at which each gene is transcribed and how much RNA is produced. This ability has allowed some eukaryotes to evolve into multicellular organisms, with distinct tissues. That is, multicellular eukaryotes use differential transcriptional regulation to create different cell types. Gene expression is influenced by three important characteristics unique to eukaryotes: the nuclear membrane, complex transcriptional regulation, and RNA processing.

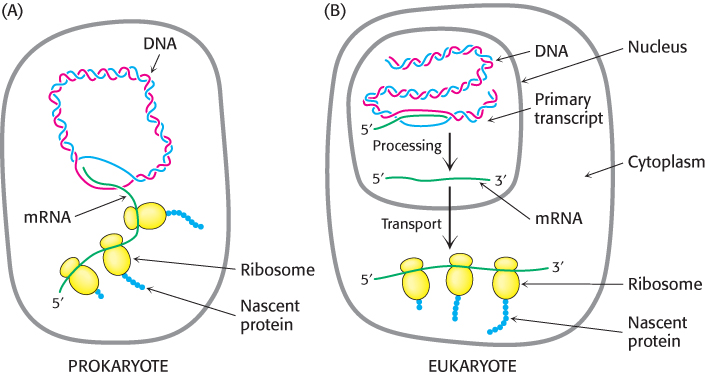

1. The Nuclear Membrane. In eukaryotes, transcription and translation take place in different cellular compartments: transcription takes place in the membrane-

872

2. Complex Transcriptional Regulation. Like bacteria, eukaryotes rely on conserved sequences in DNA to regulate the initiation of transcription. But bacteria have only three promoter elements (the −10, −35, and UP elements), whereas eukaryotes use a variety of types of promoter elements, each identified by its own conserved sequence. Not all possible types will be present together in the same promoter. In eukaryotes, elements that regulate transcription can be found at a variety of locations in DNA, upstream or downstream of the start site and sometimes at distances much farther from the start site than in prokaryotes. For example, enhancer elements located on DNA far from the start site increase the promoter activity of specific genes.

3. RNA Processing. Although both bacteria and eukaryotes modify RNA, eukaryotes very extensively process nascent RNA destined to become mRNA. This processing includes modifications to both ends and, most significantly, splicing out segments of the primary transcript. RNA processing is described in Section 29.3.

Three types of RNA polymerase synthesize RNA in eukaryotic cells

In bacteria, RNA is synthesized by a single kind of polymerase. In contrast, the nucleus of a typical eukaryotic cell contains three types of RNA polymerase differing in template specificity and location in the nucleus (Table 29.2). All these polymerases are large proteins, containing from 8 to 14 subunits and having total molecular masses greater than 500 kDa. RNA polymerase I is located in specialized structures within the nucleus called nucleoli, where it transcribes the tandem array of genes for 18S, 5.8S, and 28S rRNA. The other rRNA molecule (5S rRNA) and all the tRNA molecules are synthesized by RNA polymerase III, which is located in the nucleoplasm rather than in nucleoli. RNA polymerase II, which also is located in the nucleoplasm, synthesizes the precursors of mRNA as well as several small RNA molecules, such as those of the splicing apparatus and many of the precursors to small regulatory RNAs.

Although all eukaryotic RNA polymerases are homologous to one another and to prokaryotic RNA polymerases, RNA polymerase II contains a unique carboxyl-

Another major distinction among the polymerases lies in their responses to the toxin α-amanitin, a cyclic octapeptide that contains several modified amino acids.

|

Type |

Location |

Cellular transcripts |

Effects of α-amanitin |

|---|---|---|---|

|

I |

Nucleolus |

18S, 5.8S, and 28S rRNA |

Insensitive |

|

II |

Nucleoplasm |

mRNA precursors and snRNA |

Strongly inhibited |

|

III |

Nucleoplasm |

tRNA and 5S rRNA |

Inhibited by high concentrations |

873

α-Amanitin is produced by the poisonous mushroom Amanita phalloides, which is also called the death cap or the destroying angel. More than a hundred deaths result worldwide each year from the ingestion of poisonous mushrooms. α-Amanitin binds very tightly (Kd = 10 nM) to RNA polymerase II and thereby blocks the elongation phase of RNA synthesis. Higher concentrations of α-amanitin (1 μM) inhibit polymerase III, whereas polymerase I is insensitive to this toxin. This pattern of sensitivity is highly conserved throughout the animal and plant kingdoms.

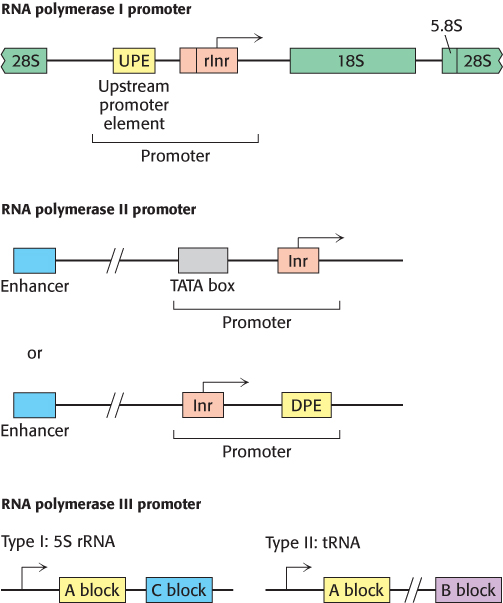

Eukaryotic polymerases also differ from each other in the promoters to which they bind. Eukaryotic genes, like prokaryotic genes, require promoters for transcription initiation. Like prokaryotic promoters, eukaryotic promoters consist of conserved sequences that attract the polymerase to the start site. However, eukaryotic promoters differ distinctly in sequence and position, depending on the type of RNA polymerase to which they bind (Figure 29.22).

1. RNA Polymerase I. The ribosomal DNA (rDNA) transcribed by polymerase I is arranged in several hundred tandem repeats, each containing a copy of each of three rRNA genes. The promoter sequences are located in stretches of DNA separating the genes. At the transcriptional start site lies a TATA-

2. RNA Polymerase II. Promoters for RNA polymerase II, like prokaryotic promoters, include a set of consensus sequences that define the start site and recruit the polymerase. However, the promoter can contain any combination of a number of possible consensus sequences. Unique to eukaryotes, they also include enhancer elements that can be very distant (more than 1 kb) from the start site.

3. RNA Polymerase III. Promoters for RNA polymerase III are within the transcribed sequence, downstream of the start site. There are two types of intergenic promoters for RNA polymerase III. Type I promoters, found in the 5S rRNA gene, contain two short conserved sequences known as the A block and the C block. Type II promoters, found in tRNA genes, consist of two 11-

874

Three common elements can be found in the RNA polymerase II promoter region

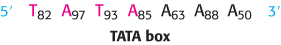

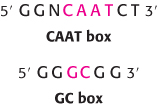

RNA polymerase II transcribes all of the protein-

The TATA box is often paired with an initiator element (Inr), a sequence found at the transcriptional start site, between positions −3 and +5. This sequence defines the start site because the other promoter elements are at variable distances from that site. Its presence increases transcriptional activity.

A third element, the downstream core promoter element (DPE), is commonly found in conjunction with the Inr in transcripts that lack the TATA box. In contrast with the TATA box, the DPE is found downstream of the start site, between positions +28 and +32.

Additional regulatory sequences are located between −40 and −150. Many promoters contain a CAAT box, and some contain a GC box (Figure 29.24). Constitutive genes (genes that are continuously expressed rather than regulated) tend to have GC boxes in their promoters. The positions of these upstream sequences vary from one promoter to another, in contrast with the quite constant location of the −35 region in prokaryotes. Another difference is that the CAAT box and the GC box can be effective when present on the template (antisense) strand, unlike the −35 region, which must be present on the coding (sense) strand. These differences between prokaryotes and eukaryotes correspond to fundamentally different mechanisms for the recognition of cis-

The TFIID protein complex initiates the assembly of the active transcription complex

Cis-

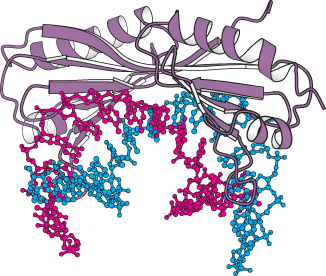

In TATA-

FIGURE 29.26 Complex formed by TATA-

FIGURE 29.26 Complex formed by TATA-875

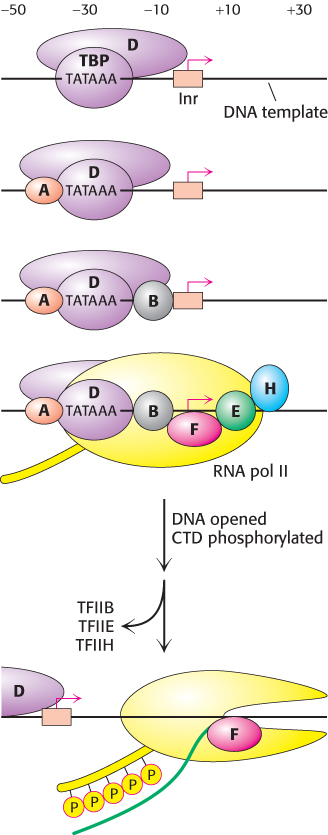

TBP bound to the TATA box is the heart of the initiation complex (Figure 29.25). The surface of the TBP saddle provides docking sites for the binding of other components. Additional transcription factors assemble on this nucleus in a defined sequence. TFIIA is recruited, followed by TFIIB; then TFIIF, RNA polymerase II, TFIIE, and TFIIH join the other factors to form a complex called the basal transcription apparatus. During the formation of the basal transcription apparatus, the carboxyl-

Multiple transcription factors interact with eukaryotic promoters

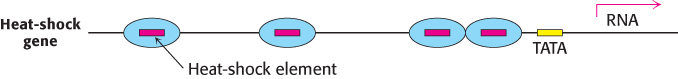

The basal transcription complex described in the preceding section initiates transcription at a low frequency. Additional transcription factors that bind to other sites are required to achieve a high rate of mRNA synthesis. Their role is to selectively stimulate specific genes. Upstream stimulatory sites in eukaryotic genes are diverse in sequence and variable in position. Their variety suggests that they are recognized by many different specific proteins. Indeed, many transcription factors have been isolated, and their binding sites have been identified by footprinting experiments. For example, heat-

Several copies of this sequence, known as the heat-

876

HSTF differs from σ32, a heat-

Enhancer sequences can stimulate transcription at start sites thousands of bases away

The activities of many promoters in higher eukaryotes are greatly increased by another type of cis-

A particular enhancer is effective only in certain cells. For example, the immunoglobulin enhancer functions in B lymphocytes but not elsewhere. Cancer can result if the relation between genes and enhancers is disrupted. In Burkitt lymphoma and B-

A particular enhancer is effective only in certain cells. For example, the immunoglobulin enhancer functions in B lymphocytes but not elsewhere. Cancer can result if the relation between genes and enhancers is disrupted. In Burkitt lymphoma and B-

Transcription factors and other proteins that bind to regulatory sites on DNA can be regarded as passwords that cooperatively open multiple locks, giving RNA polymerase access to specific genes. The discovery of promoters and enhancers has allowed us to gain a better understanding of how genes are selectively expressed in eukaryotic cells. The regulation of gene transcription, discussed in Chapter 32, is the fundamental means of controlling gene expression.

Although bacteria lack TBP, archaea utilize a TBP molecule that is structurally quite similar to the eukaryotic protein. In fact, transcriptional control processes in archaea are, in general, much more similar to those in eukaryotes than are the processes in bacteria. Many components of the eukaryotic transcriptional machinery evolved from those in an ancestor of archaea.

Although bacteria lack TBP, archaea utilize a TBP molecule that is structurally quite similar to the eukaryotic protein. In fact, transcriptional control processes in archaea are, in general, much more similar to those in eukaryotes than are the processes in bacteria. Many components of the eukaryotic transcriptional machinery evolved from those in an ancestor of archaea.