Catalytic Strategies

CHAPTER

9

251

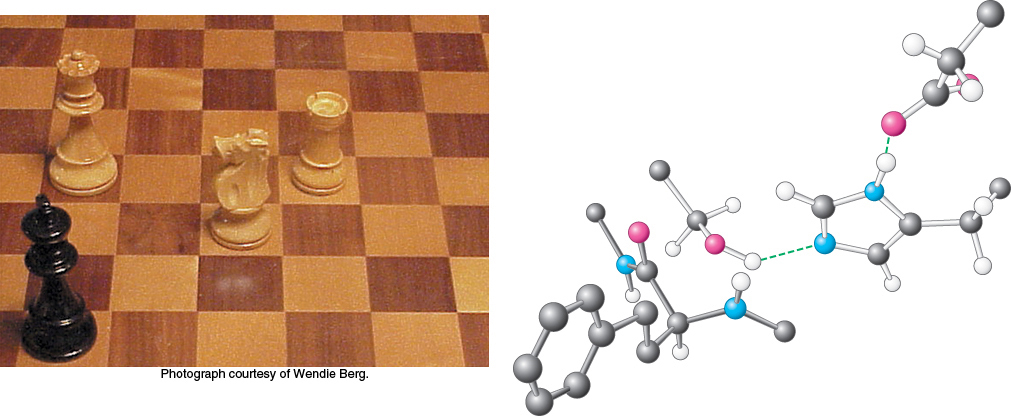

What are the sources of the catalytic power and specificity of enzymes? This chapter presents the catalytic strategies used by four classes of enzymes: serine proteases, carbonic anhydrases, restriction endonucleases, and myosins. Each class catalyzes reactions that require the addition of water to a substrate. The mechanisms of these enzymes have been revealed through the use of incisive experimental probes, including the techniques of protein structure determination (Chapter 3) and site-

Each of the four classes of enzymes in this chapter illustrates the use of such strategies to solve a different problem. For serine proteases, exemplified by chymotrypsin, the challenge is to promote a reaction that is almost immeasurably slow at neutral pH in the absence of a catalyst. For carbonic anhydrases, the challenge is to achieve a high absolute rate of reaction, suitable for integration with other rapid physiological processes. For restriction endonucleases such as EcoRV, the challenge is to attain a high degree of specificity. Finally, for myosins, the challenge is to utilize the free energy associated with the hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to drive other processes. Each of the examples selected is a member of a large protein class. For each of these classes, comparison between class members reveals how enzyme active sites have evolved and been refined. Structural and mechanistic comparisons of enzyme action are thus the sources of insight into the evolutionary history of enzymes. In addition, our knowledge of catalytic strategies has been used to develop practical applications, including potent drugs and specific enzyme inhibitors. Finally, although we shall not consider catalytic RNA molecules explicitly in this chapter, the principles also apply to these catalysts.

252

A few basic catalytic principles are used by many enzymes

In Chapter 8, we learned that enzymatic catalysis begins with substrate binding. The binding energy is the free energy released in the formation of a large number of weak interactions between the enzyme and the substrate. The use of this binding energy is the first common strategy used by enzymes. We can envision this binding energy as serving two purposes: it establishes substrate specificity and increases catalytic efficiency. Only the correct substrate can participate in most or all of the interactions with the enzyme and thus maximize binding energy, accounting for the exquisite substrate specificity exhibited by many enzymes. Furthermore, the full complement of such interactions is formed only when the combination of enzyme and substrate is in the transition state. Thus, interactions between the enzyme and the substrate stabilize the transition state, thereby lowering the free energy of activation. The binding energy can also promote structural changes in both the enzyme and the substrate that facilitate catalysis, a process referred to as induced fit.

In addition to the first strategy involving binding energy, enzymes commonly employ one or more of the following four additional strategies to catalyze specific reactions:

Covalent Catalysis. In covalent catalysis, the active site contains a reactive group, usually a powerful nucleophile, that becomes temporarily covalently attached to a part of the substrate in the course of catalysis. The proteolytic enzyme chymotrypsin provides an excellent example of this strategy (Section 9.1).

General Acid–

Base Catalysis. In general acid–base catalysis, a molecule other than water plays the role of a proton donor or acceptor. Chymotrypsin uses a histidine residue as a base catalyst to enhance the nucleophilic power of serine (Section 9.1), whereas a histidine residue in carbonic anhydrase facilitates the removal of a hydrogen ion from a zinc- bound water molecule to generate hydroxide ion (Section 9.2). For myosins, a phosphate group of the ATP substrate serves as a base to promote its own hydrolysis (Section 9.3). Catalysis by Approximation. Many reactions have two distinct substrates, including all four classes of hydrolases considered in detail in this chapter. In such cases, the reaction rate may be considerably enhanced by bringing the two substrates together along a single binding surface on an enzyme. For example, carbonic anhydrase binds carbon dioxide and water in adjacent sites to facilitate their reaction (Section 9.2).

Metal Ion Catalysis. Metal ions can function catalytically in several ways. For instance, a metal ion may facilitate the formation of nucleophiles such as hydroxide ion by direct coordination. A zinc(II) ion serves this purpose in catalysis by carbonic anhydrase (Section 9.2). Alternatively, a metal ion may serve as an electrophile, stabilizing a negative charge on a reaction intermediate. A magnesium(II) ion plays this role in EcoRV (Section 9.3).

253

Finally, a metal ion may serve as a bridge between enzyme and substrate, increasing the binding energy and holding the substrate in a conformation appropriate for catalysis. This strategy is used by myosins (Section 9.4) and, indeed, by almost all enzymes that utilize ATP as a substrate.