Comparing Girls and Boys

Given existing gender stereotypes as well as children’s early adoption of gender-typed behavior, you might assume that the actual differences between girls and boys are many and deep. Contrary to this assumption, as we will see in this section, only a few cognitive abilities, personality traits, and social behaviors actually show consistent gender differences, and most of those gender differences tend to be fairly small.

effect size  magnitude of difference between two group’s averages and the amount of overlap in their distributions

magnitude of difference between two group’s averages and the amount of overlap in their distributions

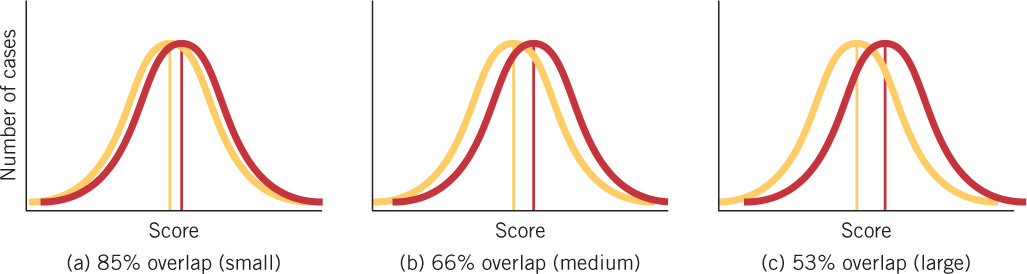

When evaluating gender comparisons for different behaviors, it is often the case that one gender differs only slightly from the other: the overlap between genders is considerable. Substantial variation also appears within each gender: not all members of the same gender are alike. Both these patterns appear in many observed gender differences studied by researchers. Therefore, besides knowing whether a group difference on some attribute is statistically significant—that is, unlikely to be caused by chance—it is important to consider both the magnitude of difference between two groups’ averages and the amount of overlap in their distributions. This statistical index, known as effect size, is illustrated in Figure 15.3.

615

Researchers generally recognize four categories of effect sizes: trivial if the two distributions overlap more than 85%; small but meaningful if the distributions overlap between 67% and 85% (Figure 15.3a); medium if the distributions overlap between 53% and 66% (Figure 15.3b); and large if the overlap is less than 53% (Figure 15.3c) (J. Cohen, 1988). Thus, sometimes even a small group difference can be statistically significant.

meta-analysis  statistical technique used to summarize average effect size and statistical significance across several research studies

statistical technique used to summarize average effect size and statistical significance across several research studies

Across different research studies, contradictory findings are common regarding gender differences or similarities in particular outcomes. Contradictory findings can occur because studies vary in the characteristics of their samples (such as participants’ ages and backgrounds) and the methods used (such as surveys, naturalistic observation, or experiments). To infer overall patterns, scientists use a statistical technique known as meta-analysis to summarize the average effect size and statistical significance across studies. When available, in this section we have used meta-analyses to summarize research on gender differences and similarities. Table 15.1 on the next page compiles average gender differences and effect sizes for specific behaviors that we consider in this section.

Because statistically significant gender differences in cognitive abilities and social behaviors are often in the small range of effect sizes, Janet Hyde (2005) has advocated “the gender similarities hypothesis.” She argued that, when comparing girls and boys, it is important to appreciate that similarities far outweigh differences on most attributes. When reviewing research findings, we acknowledge this importance by noting in Table 15.1 whether the effect size of any average gender difference in behavior or cognition is trivial, small, medium, or large. Keep in mind, however, that even when there is a large average difference on any particular measure, many girls and boys are similar to one another. Also, some members of the group with the lower average exceed some members of the group with the higher average (see Figure 15.3). For example, there is a very large average gender difference in adult height. At the same time, many women and men are the same height, and some women are taller than the average man.

616

617

Physical Growth: Prenatal Development Through Adolescence

Sex differences in physical development appear early in prenatal development. The most dramatic of these, of course, is the emergence of male or female genitalia. Thereafter, the differences that occur between males and females are relatively subtle—until the onset of puberty. In the following sections, we review the role of androgens in initiating prenatal sex differences; the average differences in male and female size, strength, and physical abilities in childhood; and the development of secondary sex characteristics in adolescence.

Prenatal Development

As should be clear from our earlier discussions, a key prenatal factor in sexual development is the presence or absence of androgens. Their presence, normally triggered by the Y chromosome in genetic males 6 to 8 weeks after conception, stimulates the formation of male external organs and internal reproductive structures; their absence results in the formation of female genital structures. In unusual circumstances known as intersex conditions (see Box 15.1), an overproduction of androgens may occur during prenatal development (congenital adrenal hyperplasia). In genetic females, this can lead to the formation of masculinized genitals. Conversely, a rare syndrome in genetic males (androgen insensitivity syndrome) causes the androgen receptors to malfunction. In these cases, female external genitalia may form.

Research suggests that prenatal exposure to androgens may influence the organization of the nervous system, and these effects may be partly related to some average gender differences in behavior seen at later ages.

Infancy

Early in life, males and females are quite similar in size, appearance, and abilities. At birth, males, on average, weigh only about half a pound more than females do; through infancy, male and female babies look so similar that, if they are dressed in gender-neutral clothing, people cannot guess their gender. Not surprisingly, it is quite easy to mislead people by, for example, dressing an infant boy in a girl’s outfit and calling him by a girl’s name. In fact, this “Baby X” technique has frequently been used to demonstrate the power of gender stereotypes. Adults who believe that they are playing with a boy are likely to encourage the infant to play with blocks and to offer the infant a toy football, even though the infant is really a girl (Bell & Carver, 1980). The technique is successful at revealing the influence of stereotyped expectations, because there are no consistent or obvious differences in how female and male infants actually look when they are clothed in a neutral manner or in how they behave.

Childhood

As discussed in Chapter 3, during childhood, girls and boys grow at roughly the same rate and are essentially equal in height and weight; however, on average, boys become notably stronger. With the changes in body composition that occur in early adolescence, particularly the substantial increase in muscle mass in boys, the gender gap in physical and motor skills greatly increases. After puberty, average gender differences are very large in strength, speed, and size: few adolescent girls can run as fast or throw a ball as far as most boys can (Malina & Bouchard, 1991; J. R. Thomas & French, 1985). These differences in motor abilities are among the largest seen between females and males (see Table 15.1).

618

Another average gender difference that increases in magnitude during childhood is activity level (Eaton & Enns, 1986). As described in Chapter 10, activity level is a temperamental quality that refers to how much children tend to move and expend energy. On average, boys’ activity level tends to be higher than that of girls. In infancy, the difference is small, meaning that there is a lot of overlap between the distributions of the two genders (see Figure 15.3a). During childhood, the average gender difference in activity level increases to medium (Figure 15.3b). This increase may result from a combination of practice effects and the greater encouragement commonly given to boys to participate in sports and other physical activities (Leaper, 2013). At the same time, average gender differences in activity level also may contribute to children’s preferences for gender-typed play activities.

Adolescence

puberty  developmental period marked by the ability to reproduce and other dramatic bodily changes

developmental period marked by the ability to reproduce and other dramatic bodily changes

menarche  onset of menstruation

onset of menstruation

A series of dramatic bodily transformations during adolescence is associated with puberty, the developmental period marked by the ability to reproduce: for boys, to inseminate, and for girls, to menstruate, gestate, and lactate. In girls, puberty typically begins with enlargement of the breasts and the general growth spurt in height and weight, followed by the appearance of pubic hair and then menarche, the onset of menstruation. Menarche is triggered in part by the increase in body fat that typically occurs in adolescence. In boys, puberty generally starts with the growth of the testes, followed by the appearance of pubic hair, the general growth spurt, growth of the penis, and the capacity for ejaculation, known as spermarche (Gaddis & Brooks-Gunn, 1985; Jorgensen, Keiding, & Skakkebaek, 1991).

spermarche  onset of capacity for ejaculation

onset of capacity for ejaculation

For both sexes, there is considerable variability in physical maturation. The variability in physical development is due to both genetic and environmental factors. Genes affect growth and sexual maturation in large part by influencing the production of hormones, especially growth hormone (secreted by the pituitary gland) and thyroxin (released by the thyroid gland). The influence of environmental factors is particularly evident in the changes in physical development that have occurred over generations (see Chapter 3). In the United States today, girls begin menstruating several years earlier than their ancestors did 200 years ago. This change is thought to reflect improvement in nutrition over the generations.

body image  an individual’s perception of, and feelings about, his or her own body

an individual’s perception of, and feelings about, his or her own body

The physical changes that boys and girls experience as they go through puberty are accompanied by psychological and behavioral changes. For example, in some cultures, the increase in body fat that girls experience in adolescence may be related to gender differences in body image—how an individual perceives and feels about his or her physical appearance. On average, American girls tend to have more negative attitudes toward their bodies than boys do, and teenage girls typically want to lose several pounds regardless of how much they actually weigh (Tyrka, Graber, & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). A survey of more than 10,000 U.S. adolescents found that roughly half of boys and two-thirds of girls were dissatisfied with their bodies. Girls were mostly concerned about losing weight; boys, with being more muscular (A. E. Field et al., 2005). Dissatisfaction with body image has long been associated with a host of difficulties, ranging from low self-esteem and depression to eating disorders. This survey added another to the list: the use of unproven and potentially harmful substances to control weight or build muscle—a practice acknowledged by 12% of the boys and 8% of the girls surveyed.

adrenarche  period prior to the emergence of visible signs of puberty during which the adrenal glands mature, providing a major source of sex steroid hormones; correlates with the onset of sexual attraction

period prior to the emergence of visible signs of puberty during which the adrenal glands mature, providing a major source of sex steroid hormones; correlates with the onset of sexual attraction

Another change that accompanies physical maturation is the onset of sexual attraction, which usually begins before the physical process of puberty is complete. According to the recollections of a sample of American adults, sexual attraction is first experienced at around 10 years of age-regardless of whether the attraction was for individuals of the other sex or the same sex (McClintock & Herdt, 1996). The onset of sexual attraction correlates with the maturation of the adrenal glands, which are the major source of sex steroids other than the testes and ovaries. This stage has been termed adrenarche, although the child’s body does not yet show any outside signs of maturation. (Sexual identity and romantic relationships are reviewed in Chapter 11 and Chapter 13.)

619

Cognitive Abilities and Academic Achievement

Although average gender differences have been reported for certain aspects of mental functioning, the amount of difference between girls’ and boys’ averages on achievement and test performance measures is usually small (D. F. Halpern, 2012; see Table 15.1). Thus, the overlap between the two distributions is large, with girls as well as boys scoring at the top and the bottom of the range. Nevertheless, despite the fact that the effect size of gender differences in abilities tends to be small, larger differences appear when it comes to interest and achievement in particular subjects. The following sections summarize the evidence comparing boys’ and girls’ cognitive abilities and achievement; then we examine biological, cognitive-motivational, and cultural influences that might account for these findings. Understanding gender differences in this area is especially important because, to the extent that girls and boys develop different cognitive abilities, academic interests, and achievement, gender differences in their future occupations and pay may follow.

General Intelligence

Despite widespread belief to the contrary, boys and girls are equivalent in most aspects of intelligence and cognitive functioning. The average IQ scores of girls and boys are virtually identical (D. F. Halpern, 2004; Hyde & McKinley, 1997). However, proportionally more boys’ than girls’ scores fall at both the lower and the upper range of scores. That is, somewhat more boys than girls are diagnosed with intellectual disabilities or classified as intellectually gifted (D. F. Halpern, 2012).

Overall Academic Achievement

Although girls and boys are similar in general intelligence, they tend to differ in academic achievement from elementary school through college. Recent statistics in the United States indicate that girls tend to show higher levels of school adjustment and achievement than do boys (T. D. Snyder & Dillow, 2010). For example, in 2010, the high school dropout rate was higher for boys (9.3%) than for girls (6.5%). In addition, in that same year, 57% of bachelor’s degrees were awarded to women. In terms of ethnic groups, the magnitude of gender difference in academic achievement is higher among Hispanic or African American youth than it is among European American or Asian American youth.

620

In addition to the overall differences in academic achievement, for some specific cognitive abilities and academic subjects, one gender tends to excel slightly more than the other.

Verbal Skills

Compared with boys, girls tend to be slightly advanced in early language development, including fluency and clarity of articulation and vocabulary development (Gleason & Ely, 2002). On standardized tests of children’s overall verbal ability, a negligible average gender difference favors girls (Hyde & Linn, 1988). Larger average differences are seen when specific verbal skills are examined. Girls tend to achieve higher average performance in reading and writing from elementary school into high school; the effect size of the average differences was small for reading and medium for writing (Hedges & Nowell, 1995; Nowell & Hedges, 1998; see Table 15.1). Boys are more likely to suffer speech-related problems, such as poor articulation and stuttering, as well as more reading-related problems such as dyslexia (D. F. Halpern, 2012).

Spatial Skills

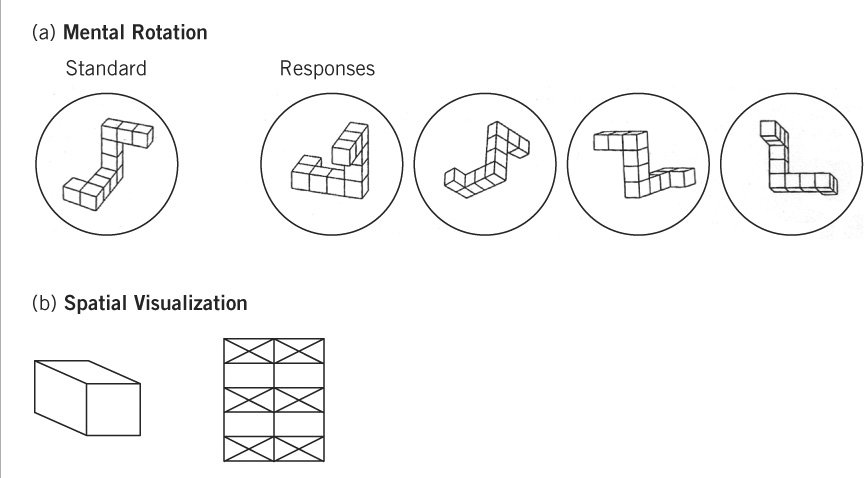

On average, boys tend to perform better than girls do in some aspects of visual-spatial processing (see Table 15.1). This difference emerges between 3 and 4 years of age and becomes more substantial during adolescence and adulthood (D. F. Halpern, 2012). Gender differences are most pronounced on tasks that involve mental rotation of a complex geometric figure in order to decide whether it matches another figure presented in a different orientation (Figure 15.4a). However, other spatial tasks, such as finding a hidden figure embedded within a larger image, show much smaller gender differences (Figure 15.4b). Thus, the conclusion that more males than females have superior spatial ability depends on the particular type of spatial ability.

Mathematical and Related Skills

Until recent decades in the United States, boys tended to perform somewhat better on standardized tests of mathematical ability than did girls. As we have noted, however, the gender gap in mathematics achievement has closed dramatically as a result of efforts made by schools to improve girls’ performance. Boys and girls currently are near parity in performance on standardized tests at the high school level (D. F. Halpern et al., 2007; Nowell & Hedges, 1998; see Table 15.1). Furthermore, U.S. girls and women are maintaining their interest in math beyond high school at rates higher than seen in earlier decades. The percentage of bachelor’s degrees in mathematics awarded to women in the United States increased from 37% in 1970 to 43% in 2010 (National Science Foundation, 2013; T. D. Snyder & Dillow, 2010).

621

Mathematics is considered a key gateway for careers in science, technology, and engineering (D. F. Halpern et al., 2007; Watt, 2006). Patterns of gender differences in these subject areas are mixed in the United States. In the life sciences (e.g., biology), girls and women appear to be doing well. At the high school level, there is no average gender difference in achievement. At the college level, women earned 59% of recent bachelor’s degrees in biological sciences (National Science Foundation, 2013).

In contrast, girls and women are not as well represented in the physical sciences (e.g., physics) and technological fields (e.g., engineering). Among recently awarded bachelor’s degrees, for example, women accounted for 20% in physics, 18% in computer science, and 18% in engineering (National Science Foundation, 2013). Following the attention paid to the gender gap in math achievement a few decades ago, educators and researchers are increasingly addressing the gender gap in the physical sciences and technology.

Explanations for Gender Differences in Cognitive Abilities and Achievement

Researchers have variously pointed to biological, cognitive-motivational, and cultural factors in relation to gender-related variations in cognitive abilities and achievement. We now examine each possible area of influence.

Biological influences Some researchers have proposed that sex differences in brain structure and function may underlie some differences in how male and female brains process different types of information. However, because the research supporting this interpretation has often been based on adults, it is impossible to determine whether any differences in brain structure and function are due to genetic or environmental influences. Also, a slight biological difference can get exaggerated through differential experience (D. F. Halpern, 2012). For example, boys may initially have a slight average advantage over girls in some types of spatial processing. However, when boys spend more time playing video games and sports than girls do, they practice their spatial skills more (Moreau et al., 2012; I. Spence & Feng, 2010). As a consequence, the magnitude of the gender difference in spatial ability may widen.

Stronger evidence for possible biological influences is suggested by research showing that some sex differences in brain structure may be partly due to the influence of sex-related hormones on the developing fetal brain (Hines, 2004). Androgens may affect parts of the brain associated with spatial skills (Grön et al., 2000), for example. Because males are exposed to higher levels of androgens than are females during normal prenatal development, this difference may lead to greater hemispheric specialization in the male brain and more proficiency in spatial ability later in life. Support for this hypothesis comes from studies that have linked very high levels of prenatal androgens in girls with above-average spatial ability (Grimshaw, Sitarenios, & Finegan, 1995; Hines et al., 2003; Mueller et al., 2008). Conversely, it has been found that males with androgen insensitivity syndrome (see Box 15.1) tend to score lower-than-average in spatial ability (Imperato-McGinley et al., 1991/2007).

622

As discussed in Chapter 6 through Chapter 9, boys are more vulnerable than girls to developmental disorders of mental functioning such as autism, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and language-related and intellectual disabilities (T. Thompson, Caruso, & Ellerbeck, 2003). Some researchers have argued that these differences may be linked to differences in brain organization and sex hormones. For example, higher rates of attention problems and language-related disorders in boys might be linked to unusually high levels of androgen exposure during prenatal development (Tallal & Fitch, 1993).

Cognitive and motivational influences The process of self-socialization emphasized in cognitive-motivational theories plays a role in children’s academic achievement. According to Eccles’s expectancy-value model of achievement (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002), children are most motivated to achieve in areas in which they view themselves as competent (expectations for success) and find interesting and important (value). Gender stereotypes can shape the kinds of subjects that girls and boys tend to value (see Table 15.1). For instance, many children internalize gender stereotypes that science, technology, and math are for boys and that reading, writing, and the arts are for girls (Archer & Macrae, 1991; J. M. Whitehead, 1996). Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that average gender differences in interest and ability beliefs exist in these academic areas (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Wigfield et al., 1997; Wilgenbusch & Merrell, 1999) and that these self-concepts predict academic achievement and occupational aspirations (Bussey & Bandura, 1999; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; D. F. Halpern et al., 2007). As discussed next, parents, teachers, peers, and the surrounding culture can influence the development of girls’ and boys’ academic self-concepts and achievement through the role models, opportunities, and motivations that they provide for practicing, or not practicing, particular behaviors.

PARENTAL INFLUENCES As noted in Chapter 6, parents’ talking to their children is a strong predictor of children’s language learning. A meta-analysis found that mothers tended to have higher rates of verbal interaction with daughters than with sons (Leaper, Anderson, & Sanders, 1998). Thus, one possibility is that young girls learn language a bit faster than boys do simply because mothers spend more time talking with daughters than sons. Conversely, girls’ faster language acquisition may lead mothers to talk more to them than to their sons (Leaper & Smith, 2004). Finally, both patterns may tend to occur—a possible bidirectional influence whereby both mothers and daughters tend to be talkative and reinforce this behavior in one another.

Parents’ gender stereotyping (see Box 15.2) is also related to children’s academic achievement. Many parents accept the prevailing stereotypes about boys’ and girls’ relative interest in and aptitude for various academic subjects (Eccles et al., 2000; Leaper, 2013), and these gender-typed expectations can affect children’s achievement motivation (Eccles et al., 2000). Observational research suggests that parents may communicate their own gender-stereotyped expectations to their children through differential encouragement (Bhanot & Jovanovic, 2005; Crowley et al., 2001; Tenenbaum & Leaper, 2003). You might think that parents’ beliefs about their children’s academic potential would be based primarily on their children’s own self-concepts and achievement, but researchers find that parents often hold these beliefs before any average gender differences in academic interest or performance occur. In fact, longitudinal research indicates that parents’ expectations can be a stronger predictor of children’s later achievement than the children’s earlier performance in particular subject areas (Bleeker & Jacobs, 2004).

623

TEACHER INFLUENCES Teachers can influence gender differences in children’s academic motivation and achievement in two important ways. First, teachers themselves are sometimes influential gender-role models. Having women as science teachers, for example, may increase girls’ interest in science careers (M. A. Evans, Whigham, & Wang, 1995). Second, many teachers hold gender-stereotyped beliefs about girls’ and boys’ abilities. For example, some teachers may expect higher school achievement in girls than in boys (S. Jones & Myhill, 2004), or they may stereotype boys as being better at math and science (Shepardson & Pizzini, 1992; Tiedemann, 2000). When teachers hold gender-typed expectations, they may differentially assess, encourage, and pay attention to students according to their gender. In this manner, teachers can lay the groundwork for self-fulfilling prophecies that affect children’s later academic achievement (see D. F. Halpern et al., 2007; Jussim, Eccles, & Madon, 1996).

PEER INFLUENCES Children’s interests often are shaped by the activities and values they associate with their classmates and friends. Consequently, peers can shape children’s academic achievement. This influence begins with the kinds of play activities that children practice with their peers. As we have noted, many activities favored by boys—including construction play, sports, and video games— provide them with opportunities to develop their spatial abilities as well as math- and science-related skills (Serbin et al., 1990; Subrahmanyam et al., 2001). The types of play more common among girls—such as domestic role-play—are talk-oriented and build verbal skills (Taharally, 1991).

Girls and boys may be more likely to achieve in particular school subjects when they are viewed as compatible with peer norms. For example, one study found that U.S. high school students who viewed their friends as supportive of science and math were more likely to express interest in a future science-related career (Robnett & Leaper, 2013). The association between friends’ science support and science career interest held for both girls and boys—but boys were more likely than girls to report having a friendship group supportive of science. It is also notable that friends’ support of English (reading and writing) was not related to science career interest; thus, peer norms regarding particular academic subjects may be related to how likely girls or boys are to value those subjects.

624

Traditional masculinity norms emphasizing dominance and self-reliance may undermine some boys’ academic achievement in the United States and other Western countries (Levant, 2005; Renold, 2001; Steinmayr & Spinath, 2008; Van Houtte, 2004). That is, some boys may not consider it masculine to do well in certain subjects or possibly in school overall. For example, doing well in school or expressing interest in certain subjects, such as reading, may be devalued as being feminine (Andre et al., 1999; Martinot, Bagès, & Désert, 2012; J. M. Whitehead, 1996). Indeed, some research suggests that boys’ endorsement of traditional masculinity is related to lower average performances in reading and writing and lower rates of high school graduation in North America and Europe (Levant, 2005; Renold, 2001; Steinmayr & Spinath, 2008; Van de Gaer et al., 2006; Van Houtte, 2004). At the same time, some U.S. research suggests that gender-role flexibility is related to holding more positive scholastic self-concepts in adolescent boys (A. Rose & Montemayor, 1994), as well as to stronger interest in nontraditional majors among male undergraduates (Jome & Tokar, 1998; Leaper & Van, 2008).

CULTURAL INFLUENCES Social role theory maintains that socialization practices prepare children for their adult roles in society. If women and men tend to hold different occupations, then different abilities and preferences are apt to be encouraged in girls and boys. Therefore, where there are cultural variations in girls’ and boys’ academic achievement, there should be corresponding differences in socialization.

A meta-analysis conducted by Else-Quest, Hyde, and Linn (2010) pointed to cultural influences on gender-related variations in mathematics achievement. Gender differences on standardized math tests varied widely across nations: in some, boys scored higher; in others, girls scored higher; and in still others, no gender difference appeared. To assess possible cultural influences, the researchers considered the representation of women in higher education in the country. They found that average gender differences in several math-related outcomes were less likely in nations with higher percentages of women in higher levels of education. This was seen for adolescents’ test performance, self-confidence, and intrinsic motivation regarding math. As we noted earlier, the narrowing gender gap in math achievement in the United States over the past few decades was accompanied by a steady increase in the proportion of women in science and engineering (National Science Foundation, 2013).

Other cultural factors have also been found to predict gender-related variations in academic achievement within American society. Average gender differences in overall academic success and verbal achievement tend to be less common among children from higher-income neighborhoods and among children of highly educated parents (Burkam, Lee, & Smerdon, 1997; DeBaryshe, Patterson, & Capaldi, 1993; Ferry, Fouad, & Smith, 2000). Gender differences in achievement may also be less common among children of gender-egalitarian parents. One study found that adolescent girls raised by egalitarian parents maintained higher levels of academic achievement in middle school—especially in math and science—compared with girls raised by more traditional parents (Updegraff, McHale, & Crouter, 1996).

625

Personality Traits

During childhood, average gender differences appear in some personality traits, including activity level, self-regulation, and risk-taking (see Table 15.1). Keep in mind, however, that there is much overlap between girls and boys. In other words, many girls and boys express similar personality traits. Also, there is variation within each gender in personality. Not all girls are alike, and not all boys are alike.

Activity level

Higher average activity levels are seen among boys than among girls during childhood. The effect size is medium, which means that there is a meaningful average difference (although there is also much overlap between the two genders). Children’s activity levels may partly underlie some average differences between girls and boys in how much they prefer active versus sedentary forms of play—such as sports and doll play, respectively.

Self-Regulation

As discussed in Chapter 10, self-regulation refers to children’s ability to control their own emotions and behavior, to comply with adults’ directions, and to make good decisions when adults are not around. Research indicates that girls tend to show higher levels of self-regulation and lower impulsivity than do boys of the same age—with the average gender difference being in the small-to-large range, depending on the type of measure used (Else-Quest et al., 2006). Given the average gender difference in self-regulation, perhaps it is not surprising that, on average, girls are more compliant with adult directives and expectations than boys are (C. L. Smith et al., 2004). As discussed later, average gender differences in self-regulation and impulsivity may partly contribute to higher incidences of direct physical aggression among boys than girls.

Risk Taking

A third personality trait associated with average gender differences during childhood is risk taking. There is a small average difference across studies indicating that boys are more likely than girls to engage in many types of risky behavior (Byrnes, Miller, & Schafer, 1999). When boys and girls encounter the same hazardous situation, for example, girls are more cautious, on average, and often point out the hazard to a parent. In contrast, boys are more likely to approach and explore the hazard (Fabes, Martin, & Hanish, 2003).

Explanations for Gender Differences in Personality

As with other aspects of gender development, there is evidence for both biological and cognitive-motivational influences on average gender differences in personality. Activity level and impulse control are temperamental qualities that are partly based on genetic predispositions (see Chapter 10). In addition, environmental factors—such as parents’ and peers’ reactions—can exaggerate or attenuate temperamental dispositions (Goldsmith, Buss, & Lemery, 1997). For instance, some parents encourage athletic participation more in sons than in daughters. Also, peer pressures on boys to participate in sports are often stronger than on girls (see Leaper, 2013). As a consequence of these socialization practices, preferences for physical activity may strengthen in boys and weaken in girls.

626

Interpersonal Goals and Communication

One of the most popular self-help books about relationships has been John Gray’s (1992) Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus. The author (who is not a scientist) purported that gender differences in interpersonal goals and communication style are so great that it is almost as if the sexes came from different planets. The scientific evidence, however, indicates that average gender differences in adults’ communication are not nearly as dramatic as Gray portrayed them. Although average gender differences in women’s and men’s speech have been documented, the magnitude of the differences has usually been in the small-to-medium range (Leaper & Ayres, 2007). The average gender differences in communication and interpersonal goals during childhood and adolescence have likewise been found to be modest (see Table 15.1).

In terms of interpersonal goals, researchers have found average gender differences that are consistent with traditional gender roles (A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006). More boys than girls tend to emphasize dominance and power as goals in their social relationships. In contrast, more girls than boys tend to favor intimacy and support as goals in their relationships. The effect sizes for these differences tend to be small to moderate.

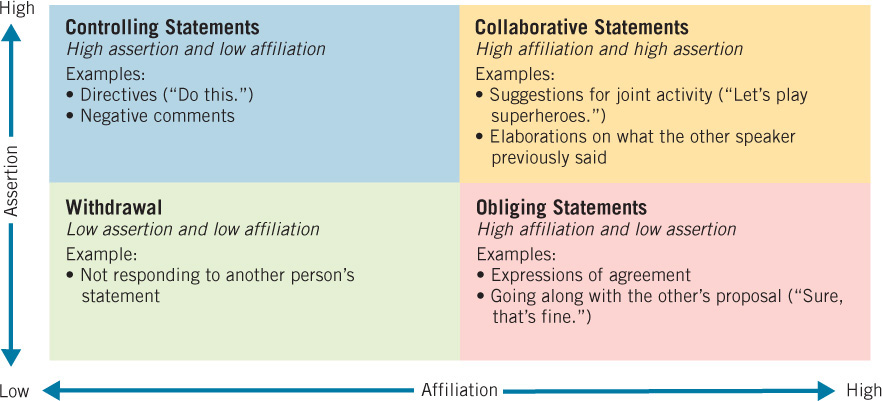

Researchers have also observed some average gender differences among children in communication style with their peers. Contrary to the stereotypes of talkative girls and taciturn boys, studies generally do not find average differences in talkativeness after early childhood (Leaper & Smith, 2004). However, with regard to self-disclosure about personal thoughts and feelings, there tends to be a small-to-medium gender difference, with higher average rates among girls than boys (A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Girls also tend to be somewhat more likely than boys to use collaborative statements, which reflect high affiliation and high assertion. In contrast, boys tend to be more likely than girls to use directive statements, which reflect high assertion and low affiliation (see Box 15.5).

Cognitive and motivational influences The average gender differences in interpersonal goals and communication style are related. To the extent that some girls and boys differ in their primary goals for social relationships, they are apt to use different language styles to attain those goals (P. M. Miller, Danaher, & Forbes, 1986; Strough & Berg, 2000). For example, if a boy is especially interested in establishing dominance, using directive statements may help him attain that goal; and if a girl wants to establish intimacy, then talking about personal feelings or elaborating on the other person’s thoughts would help realize that goal.

Parental influences Many children may observe their parents modeling gender-typed communication patterns. A meta-analysis comparing mothers’ and fathers’ speech to their children indicated small average effect sizes, with mothers more likely than fathers to use affiliative speech; in contrast, fathers were more likely than mothers to use controlling (high in assertion and low in affiliation) speech (Leaper, Anderson, & Sanders, 1998).

627

Box 15.5: a closer look

GENDER AND CHILDREN’S COMMUNICATION STYLES

Several studies conducted by Leaper and colleagues have examined gender-related variations in children’s and adults’ communication patterns (e.g., Leaper, 1991; Leaper et al., 1999; Leaper et al., 1995; Leaper & Gleason, 1996; Leaper & Holliday, 1995). In one study of 5- and 7-year-olds, Leaper (1991) placed children in same- or mixed-gender pairs to play with a set of hand puppets. He recorded the children’s conversation and classified each statement the children made in terms of affiliation and assertion. As diagrammed in the figure below, a statement can be high or low on each dimension, which allows for four speech act (statement) categories:

- Collaborative statements are high in both affiliation (engaging the other person) and assertion (guiding the action). Examples include suggestions for joint activity (“Let’s play superheroes”) or elaborations on what the other speaker previously said.

- Controlling statements are high in assertion but low in affiliation. Examples include directives (“Do this”) or negative comments.

- Obliging statements are high in affiliation and low in assertion. Examples include expressions of agreement or going along with the other’s proposal (“Sure, that’s fine”).

- Withdrawing acts reflect low assertion and low affiliation. This includes being nonresponsive to another person’s statement.

For girls and boys in both age groups, collaborative conversations were the most common. There were no average gender differences in any of the types of statements among the younger children and there were no average differences in obliging statements or withdrawing acts among the older children. However, significant gender differences were seen among the older children in the percentages of collaborative and controlling statements. Among the 7-year-olds, the average percentage of collaborative statements was significantly higher among girl–girl pairs (mean = 56%) than either boy–boy pairs (mean = 39%) or mixed-gender pairs (mean = 43%).

Following is an example of reciprocal collaboration between one pair of girls. The type of speech act is indicated in brackets next to each statement.

Jennifer: Let’s go play on the slide. (Makes sliding noises) [Collaborate]

Sally: Okay. [Oblige] (Makes sliding noises) I’ll do a choo-choo train with you. [Collaborate]

Jennifer: Okay. [Oblige]

Sally: You can go first. [Collaborate]

Jennifer: Ch…(Gasp) [Collaborate]

Sally: Ch…(Gasp) [Collaborate]

(Leaper, 1991, p. 800)

Another average gender difference was the percentage of controlling speech. Rates were significantly lower in girl–girl pairs (mean = 13%) than either boy–boy pairs (mean = 26%) or mixed-gender pairs (mean = 24%).

Within the mixed-gender pairs, no gender differences appeared in collaborative or controlling speech. Thus, it appears that girls tended to decrease their amount of collaborative speech and increase their use of controlling speech when interacting with boys (compared with when they are interacting with girls). Conversely, boys tended to use similar amounts of collaborative and controlling speech in same-gender and mixed-gender interactions.

According to Leaper (1991), it is important to acknowledge, first, that collaboration was the most common type of speech for both girls and boys. Despite this similarity, collaboration was even more frequent in the average speech of girls than of boys. Conversely, controlling speech was more common among boys than among girls. Contrary to old stereotypes of girls being unassertive, girls were not more likely than boys to make statements low in assertion (obliging speech or withdrawing). Instead, girls were more likely to coordinate affiliative and assertive goals in their communication. Finally, in mixed-gender interactions, there was more evidence of girl’s accommodating to the speech style of boys than the reverse; that is, girls tended to show more of the pattern associated with boys’ same-gender interactions (more controlling and less collaborative speech) during mixed-gender interactions, whereas boys tended to show similar average patterns in same- and mixed-gender interactions.

628

Peer influences The social norms and activities traditionally practiced within children’s gender-segregated peer groups foster different interpersonal goals in girls and boys. For example, many girls commonly engage in domestic scenarios (“playing house”) that are structured around collaborative and affectionate interchanges. Boys’ play is more likely to involve competitive contexts (“playing war” or sports) that are structured around dominance and power. The impact of same-gender peer norms was implicated in Leaper and Smith’s (2004) meta-analysis in which it was found that gender differences in communication were more likely to be detected in studies of same-gender interactions than in mixed-gender interactions.

Aggressive Behavior

The conventional wisdom is that boys are more aggressive than girls are. In support of this expectation, research studies indicate a reliable gender difference in aggression. However, the magnitude of the gender difference is not as great as many people expect. Also, it depends partly on the type of aggression being considered.

As noted in Chapter 13, researchers distinguish between direct and indirect forms of aggression (Archer & Coyne, 2005; Björkqvist, Österman, & Kaukiainen, 1992). Direct aggression involves overt physical or verbal acts openly intended to cause harm, whereas indirect aggression (also known as relational or social aggression) involves attempts to damage a person’s social standing or group acceptance through covert means such as negative gossip and social exclusion.

Average gender differences in the incidence of physical aggression emerge gradually during the preschool years (D. F. Hay, 2007). In a comprehensive meta-analysis of studies comparing boys’ and girls’ aggressive behavior, John Archer (2004) found that both physical and verbal forms of direct aggression occurred more often among boys than among girls. The average difference was small during childhood and moderate to large during adolescence. Although direct aggression generally declines for both boys and girls with age, the decline is more pronounced for girls than for boys.

There appears to be no average gender difference during childhood in the use of indirect aggression. In a meta-analysis of studies testing for such gender differences, Card and colleagues (2008) found only a negligible effect size during adolescence, with girls slightly more likely than boys to use indirect aggression. The trivial effect size may seem surprising given the popular notion of “mean girls” who use indirect strategies such as negative gossip and social exclusion. However, because direct aggression is less likely among girls than boys, girls tend to use proportionally more indirect than direct aggression than boys, on average. Thus, when most girls do express aggression, it may be indirect rather than direct physical or verbal aggression (Leaper, 2013).

Although there may not be much difference between girls and boys in the average use of indirect aggression, being the target of indirect aggression may more often cause problems for girls than boys (Crick & Grotpeter, 1996). This may occur because girls’ friendships tend to be exclusive and intimate, whereas boys’ friendships tend to be embedded within a larger peer group (Benenson et al., 2002; A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Nonetheless, all forms of aggression can have negative effects on both girls and boys.

629

Average gender differences in aggression have been found primarily in research on same-gender interactions. Research conducted with mostly European American children suggests that different rules may apply when some girls and boys have conflicts with one another. Beginning in early childhood, boys are more likely than girls to ignore the other gender’s attempts to exert influence (Jacklin & Maccoby, 1978; Serbin et al., 1982). Thus, when they are more assertive and less affiliative, boys may be more apt to get their way in unsupervised mixed-gender groups (Charlesworth & LaFreniere, 1983).

Studies comparing children’s behavior in same-gender versus cross-gender conflicts revealed another interesting pattern. In same-gender conflicts, boys were more likely to use power-assertive strategies (e.g., threats, demands) and girls were more likely to use conflict-mitigation strategies (e.g., compromise, change the topic). However, in cross-gender conflicts, girls’ use of power-assertive strategies increased, but boys’ use of conflict-mitigation strategies did not change (P. M. Miller et al., 1986; Sims, Hutchins, & Taylor, 1998). These studies suggest that girls often may find it necessary to play by the boys’ rules to gain influence in mixed-gender settings.

Explanations for Gender Differences in Aggression

Possible explanations for gender differences in aggression range from the effects of biological factors to the socializing influences of family, peers, the media, and the culture at large. Each factor likely has a contributing role.

Biological influences It is well known that, on average, males have higher baseline levels of testosterone than do females, and many people assume that this accounts for gender differences in aggression. Contrary to this popular belief, there is no direct association between aggression and baseline testosterone levels (Archer, Graham-Kevan, & Davies, 2005). However, there is an indirect one: the body increases its production of testosterone in response to perceived threats and challenges, and this increase can lead to more aggressive behavior (Archer, 2006). Furthermore, people who are impulsive and less inhibited are more likely to perceive the behavior of others as threatening. Thus, because boys, on average, have more difficulty regulating emotion (Else-Quest et al., 2006), they may be more prone to direct aggression (D. F. Hay, 2007). Conversely, greater emotion regulation among girls may contribute to higher rates of prosocial behavior.

Cognitive and motivational influences Average gender differences in empathy and prosocial behavior may be related to differences in boys’ and girls’ rates of aggression (Knight, Fabes, & Higgins, 1996; Lemerise & Arsenio, 2000; Levant, 2005; Mayberry & Espelage, 2007). On average, girls are somewhat more likely than boys to report feelings of empathy and sympathy in response to people’s distress (N. Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998), and they also tend to display more concern in their behavioral reactions (e.g., looks of concern and attempts to help). Direct aggression may be more likely among children who are less empathetic and have fewer prosocial skills. In support of this explanation, one study found average gender differences, with boys scoring higher on direct aggression and lower on empathy than girls, but both aggressive girls and aggressive boys scored lower on empathy than did nonaggressive girls and boys (Mayberry & Espelage, 2007).

630

The gender-typed social norms and goals regarding assertion and affiliation may further contribute to the average gender difference in conflict and aggression (P. M. Miller et al., 1986; A. J. Rose & Rudolph, 2006; see Table 15.1). More boys than girls tend to favor assertive over affiliative goals (e.g., being dominant), whereas more girls than boys tend to endorse affiliative goals or a combination of affiliative and assertive goals (e.g., maintaining intimacy). When some boys focus on dominance goals, they may be more likely to appraise conflicts as competitions that require the use of direct aggression. In addition, some boys may initiate direct aggression as a way to enhance their status.

In contrast, by emphasizing intimacy and nurturance goals, many girls may be more likely to view relationship conflicts as threats that need to be resolved through compromise that preserves harmony (P. M. Miller et al., 1986). The normative social pressures among many girls to act “nice” may also lead them to avoid direct confrontation. However, when girls who adhere to these norms are unable to resolve a conflict, they may try to hurt one another through indirect strategies such as criticizing or excluding the offender or sharing secret information about the offender with other girls (Crick, Bigbee, & Howes, 1996; Galen & Underwood, 1997). This may be one reason for a paradox noted in Chapter 13: Even though girls, on average, have more intimate friendships than do boys, girls’ same-gender friendships tend to be less stable over time (Benenson & Christakos, 2003). That is, when conflict occurs in same-gender friendships and indirect aggression occurs, girls may be more likely than boys to take it personally and see it as a reason to end the relationship.

Parental and other adult influences In general, most parents and other adults disapprove of physical aggression in both boys and girls. After the preschool years, however, they tend to be more tolerant of aggression in boys and often adopt a “boys will be boys” attitude toward it (J. Martin & Ross, 2005). In an experimental demonstration of this effect, researchers asked people to watch a short film of two children engaged in rough-and-tumble play in the snow and to rate the level of the play’s aggressiveness (Condry & Ross, 1985). The children were dressed in gender-neutral snowsuits and filmed at a distance that made their gender undeterminable. Some viewers were told that both children were male; others, that they were both female; and still others, that they were a boy and girl. Viewers who thought that both children were boys rated their play as much less aggressive than did viewers who thought that both children were girls.

Children also appear aware of this “boys will be boys” bias and believe that physical aggression is more acceptable, and less likely to be punished, when enacted by boys than when enacted by girls (Giles & Heyman, 2005; Perry, Perry, & Weiss, 1989). Thus, girls’ reliance on strategies of aggression that are covert—and easily denied if detected—may reflect their recognition that displays of physical aggression on their part will attract adult attention and punishment.

Parenting style may also factor into children’s manifestations of aggression. Harsh, inconsistent parenting and poor monitoring increase the likelihood of physical aggression in childhood (Leve, Pears, & Fisher, 2002; Vitaro et al., 2006). Children who experience such parenting may learn to mistrust others and make hostile attributions about other people’s intentions (Crick & Dodge, 1996). The association between harsh parenting and later physical aggression is stronger for boys than for girls. Also, as noted in Chapter 14, poor parental monitoring increases children’s susceptibility to negative peer influences and is correlated with higher rates of aggression and delinquency (K.C. Jacobson & Crockett, 2000). Thus, the fact that parents monitor daughters more closely than sons may contribute to gender differences in aggression.

631

Peer influences Gender differences in aggression are consistent with the gender-typed social norms of girls’ and boys’ same-gender peer groups. However, it is worth noting that children who are high in aggression and low in prosocial behavior are typically rejected in both male and female peer groups (P. H. Hawley, Little, & Card, 2008). These children tend to seek out marginal peer groups of other similarly rejected peers, and these contacts strengthen the likelihood of physical aggression over time (N. E. Werner & Crick, 2004).

Another peer influence on aggression may be boys’ regular participation in aggressive contact sports, which sanction the use of physical force and may contribute to higher rates of direct aggression among boys (Messner, 1998). Support for this proposal is the finding that participation in aggressive sports, such as football, in high school is correlated with a higher likelihood of sexual aggression in college (G. B. Forbes et al., 2006). As explained in Box 15.6, aggressive behaviors may also involve sexual harassment.

Box 15.6: applications

SEXUAL HARASSMENT AND DATING VIOLENCE

Sexual harassment commonly affects both boys and girls and can involve direct (physical or verbal) or indirect (relational) aggression. Physical sexual harassment involves inappropriate touching or forced sexual activity. Verbal sexual harassment involves unwanted, demeaning, or homophobic sexual comments, whether spoken directly to the target or indirectly, behind her or his back. Also, verbal harassment commonly spreads via electronic media (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2007).

Surveys in the United States and Canada indicate that the vast majority of both girls and boys have experienced sexual harassment during adolescence (American Association of University Women, 2011; Leaper & Brown, 2008; McMaster et al., 2002). Most teen sexual harassment occurs in school hallways and classrooms, and the perpetrators are more likely to be peers rather than teachers or other adults. In an American Association of University Women (AAUW) survey (2011), 56% of girls and 40% of boys in middle and high school reported having experienced sexual harassment at least once during the prior year. Other surveys suggest that rates of sexual harassment may be higher for sexual-minority (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex) youths (Williams et al., 2005). Studies indicate that sexual harassment is also a problem for teens in many parts of the world (see Leaper & Robnett, 2011).

Two of the most frequent forms of reported sexual harassment in the AAUW survey were unwanted sexual comments or gestures (46% of girls, 22% of boys) and being called gay or lesbian in a negative way (18% of girls, 19% of boys). When the adolescents were asked to indicate whether and how sexual harassment affected them, girls were more likely than boys to report negative effects. The most common responses to sexual harassment included not wanting to go to school (37% of girls, 25% of boys) and finding it difficult to study (34% of girls, 24% of boys). Boys were more likely than girls to report that experiences with sexual harassment had no effect on them (17% of boys, 10% of girls).

Girls may tend to have more negative reactions to sexual harassment than do boys partly because girls are somewhat more likely than boys to experience repeated sexual harassment. Also, because of traditional masculine socialization, boys may be more reluctant to admit vulnerability. Regardless of the individual’s gender, repeated experiences with sexual harassment can have long-term negative consequences on girls’ and boys’ self-esteem and adjustment (S. E. Goldstein et al., 2007; Gruber & Fineran, 2008).

Sexual harassment and violence also occur in dating relationships. Physical aggression occurs in an estimated one-fourth of adolescent heterosexual dating relationships (Hickman, Jaycox, & Aronoff, 2004; O’Leary et al., 2008), with boys being more likely to be the perpetrators (Swahn et al., 2008; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008). As a consequence, many girls come to regard demeaning behaviors as normal in heterosexual relationships (Witkowska & Gådin, 2005), and they therefore may be at risk for dysfunctional and abusive relationships in adulthood (Larkin & Popaleni, 1994). Although there have been fewer studies of dating violence in lesbian and gay teens’ relationships, one survey indicated that the prevalence of dating violence among sexual-minority youths was similar to that among heterosexual youths (Freedner et al., 2002).

Media influences A common question for parents and researchers is whether frequently watching violent TV shows and movies or playing violent video games has a negative impact on children. As you might expect, boys are more likely than girls to devote time to these activities (Cherney & London, 2006). One possible inference is that consuming more violent media may contribute to average gender differences in physical aggression.

632

Our discussion of media violence in Chapter 9 makes clear that viewing aggression in movies, TV programming, and video games is associated with children’s aggressive behavior and that this holds true for girls as well as for boys. Several experimental studies point to a causal influence. That is, the likelihood of aggression increases in some children after watching violent programs (Paik & Comstock, 1994) or playing violent videogames (Ferguson, 2007). Exposure to violent media may lead to increased arousal and decreased inhibition, which may stimulate aggression in some children (Coyne & Archer, 2005). However, rather than causing aggression, the effect might more likely be correlated with children who are also prone toward aggressive behavior for additional reasons.

Whereas boys are more likely than girls to favor TV shows and movies with violent content, one study found that adolescent girls were more likely than boys to prefer shows depicting indirect aggression (Coyne & Archer, 2005). Furthermore, an experimental study demonstrated that observing indirect aggression on TV increased the subsequent likelihood of indirect aggressive behavior but had no impact on direct aggression (Coyne, Archer, & Eslea, 2004).

Other cultural influences Although gender differences in aggression have been observed in all cultures, cultural norms also play an important role in determining the levels of aggression that are observed in boys and girls. Douglas Fry (1988) studied rural communities in the mountains of Mexico and found that the levels of childhood aggression that were considered normal varied widely from one area to another. Boys in each community showed more aggression than girls did. However, girls in the high-aggression communities were more aggressive than boys in the low-aggression communities.

The community context must also be considered in relation to the emergence of differential rates of aggression among U.S. youth. Levels of violence are high in many U.S. communities, particularly in inner-city areas where an estimated 40% to 60% of children have witnessed violent crimes within the previous year (Osofsky, 1995). When children are exposed to violence in their homes and communities, boys and girls both experience an increased risk of emotional and behavioral problems and show an increase in aggressive behaviors. However, boys are more likely than girls to be exposed to the highest levels of violence, and the average impact of exposure is also greater for boys than for girls (Guerra, Huesmann, & Spindler, 2003).

633

review:

Gender development begins before birth when the genes program the developing embryo to form female or male genitalia. In the absence of androgen hormones triggered by the Y chromosome, female genitalia form. The higher production of androgens in genetic males (and, in rare cases, in genetic females) may influence brain organization and functioning. Physical changes during puberty typically lead to increased muscle mass in boys as well as large average advantages in strength, speed, and size. Also, puberty leads to bodily transformations that allow for each sex’s reproductive ability.

Although the common impression is that girls and boys are inherently and deeply different in their cognitive and social behaviors, in most respects the similarities between them outweigh the differences. As summarized in Table 15.1, even when differences are consistently reported, they tend to be fairly small. Also, many average differences do not emerge until later in childhood or adolescence. The most substantial differences are found in physical strength and speed, specific spatial abilities (e.g., mental rotation), academic achievement, self-regulation, activity level, and physical aggression. Small average gender differences are seen in verbal ability, risk taking, interpersonal goals, and communication style. A combination of biological, cognitive-motivational, and cultural influences are implicated to varying degrees in most of these differences.